|

Do I exercise to be healthy or to look a certain way? If being healthy meant looking unattractive, which would I choose? Or consider the question the other way around: if looking attractive meant being unhealthy, which would I choose?

Let's start with something simple: health. It is a big reason why I personally do physical exercises and make nutritional choices. Based on scientific as well as cultural knowledge, I believe that moving my body around — getting my heart rate up, maintaining the strength and mobility of my joints — will cause my life to be freer from pain, and perhaps even cause me to live longer and stay physically capable longer. This leads us to two further inquiries: why do I want to be free of pain, and why do I want to live longer? The pain aspect is pretty straightforward, as every living being can feel pain and strives to avoid it. The question of longer life is more interesting, especially to a yogi. Do we want to live longer because of the important work we are doing? Or because we want to travel as much as possible? Or because we are afraid of not being alive anymore? These questions are worth considering in your own life. Let's move on to a further implication of exercise and health: it generally causes the body to burn fat, build muscle, and be what is culturally accepted as attractive. Indeed, some conceptions of beauty consider that it is connected to health — that we are subconsciously attracted to healthy people because they will make more robust mates. It is probably a bit more complicated than that, as different eras and cultures find different qualities physically attractive. At the moment in the West, thin and athletic bodies are all the rage. In my own physical practice, my purposes are health and function. Regardless of how my body ends up looking, I try to do the practices that will make me healthy. If it is healthy for me to have big shoulders and a big butt, I am fine with that. If the opposite is true — small shoulders and a small butt — I am fine with that too. I try not to focus on the aesthetic outcome of the practices, but rather the functional outcome.

0 Comments

It's easy to find things that pique our interest. We see or hear about something new—a new posture, sport, skill, craft or hobby. We think, "That would be good for me!" Or, "I might like that."

Soon, that initial excitement starts to fade. But, committed to the idea of our new passion, we still gather equipment, books, videos and anything else that we think might help us develop our new curiosity. Then those things sit there. The how-to books are in a pile, the equipment in a corner. Now we are left with a different type of wanting. This is not the desire to actually do or learn, but the want to want to do it. Now we have a choice: use discipline or move on. We can either double down and do the activity anyway, despite our lack of enthusiasm, or we can give it up and move on to something else. Either can be the right answer. It just depends on the goal. To determine which answer is the best one, we should consider the why. When it comes to a yoga practice, the why is very important. It is not a good reason to take up a yoga practice if we just want to see ourselves as a yogi, or have others see us this way. It's easy to get caught up in the idea of appearing spiritual without having the desire to actually walk the path. This is one reason for wanting to want to practice: we like the idea of what it would mean, but don't want to actually do the work. There may be other simpler reasons for wanting to want to practice. It could be that we simply feel tired and need to rest. But the desire to appear as though we practice yoga is important to be aware of. In this case, it may be better to give up the practice entirely. If our desire to practice yoga comes from the desire to strengthen our egoic self, it may be a more yogic action to give up yoga. Yoga, like pretty much every other skill, relies on a combination of factors. Two of the most important are knowledge and practice. Knowledge is our understanding of more theoretical concepts: why we are doing it, what is the underlying belief system, how might I improve, etc. Practice is the actual putting-in-motion of these concepts: the hours, days, months and years of using the body and mind to build experience and generate progress.

These two are powerful when used together. They are much less impactful when apart. KNOWLEDGE Knowing what you believe, why you believe it, what you're practicing and why is absolutely essential to any sort of progress. If you don't know these things, any effort you exert could easily be put in the wrong direction, taking you further from your goals rather than closer to them. If you want to go north but don't have a compass, it doesn't matter how fast you run. You are likely to unknowingly head in the wrong direction, getting further from your goal. And the harder you work, the further you get. Yoga practice is the same way. Whether you're trying to improve your balance, stand on your hands, breathe better, or have deep meditation, it is essential to first know what to do. Each of these goals will require different techniques, and if you use the wrong one you will essentially make progress in the wrong direction. Therefore knowledge is indispensable to progress. Effort or practice without knowledge can be futile and counterproductive. This can lead to frustration. Often, when you feel stuck in your practice, it is greater knowledge rather than greater effort that will help. Knowledge helps us refine our understanding of who we are, where we are, where we want to go, and how to get there. PRACTICE The other half of the conversation is the effort we exert toward our goals — practice. It may be obvious to say, but this is where the actual progress happens. If you want to go north and you know which direction is north, you still have to put one foot in front of the other and actually go north. No amount of knowing will get you there. It is easy for intellectual people to overemphasize knowledge. We think that if we know more, then we will make more progress. We continually collect and consume copious amounts of information and knowledge. But we make limited progress this way. Knowledge must be accompanied by practice, because our bodies and minds grow through use. To improve our balance, we must allow the body to learn how to connect the feet, legs, hips, etc. No amount of study will do this. Only actual practice. Also, study uses the mind in a specific way, essentially practicing one skill. If we study a lot, we will get good at studying. But we won't improve other skills, like balancing, breathing or meditating. To progress at those, we must practice them. PUTTING THEM TOGETHER There is a well-known saying in the yoga world, often attributed to K. Pattabhi Jois, the founder of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga: "Yoga is 99% practice, 1% theory." The quotation is probably hyperbolic, intended to make a point. But the danger in this mentality is that it may encourage thoughtless practice and effort. To return to our analogy, it is like saying "99% walking, 1% checking the compass." As teachers, we speculate that the lesson Jois was trying to teach is: Don't get stuck in thinking about things. And don't think that knowledge will save you or be enough on its own. You must practice. We agree with this, but we also think that the opposite is equally likely. Students may think that practice and effort are enough on their own. Then they will cultivate very little knowledge or understanding of what they're doing and why. They will end up making progress in the wrong direction. We think that the two are equally important: 50% practice, 50% knowledge. The two feed and inform each other. Your actual practice will help you understand why ancient scriptures say what they do. And your knowledge of history, philosophy, and your own goals will help your practice be more effective and productive. Many of us believe that yoga is a reprieve from the hectic outside world. Our outer lives are fast and stressful while the inner yogic world is calm and peaceful. But yoga is a system that has real-world consequences. You may have noticed that your thoughts, beliefs and actions have changed since you began practicing or studying yoga. And when our actions change, consequences change.

As such, yoga has a long history of interaction with social and political issues. It will be useful to examine some of yoga's core tenets, because they inevitably have an impact in the real world. We want to examine the real-world impact of yoga in three articles. This is the first. Here let's look at some of the fundamental tenets of yoga philosophy: non-violence & truth. NON-VIOLENCE A central belief in yoga and much Eastern philosophy is non-violence. At its heart, this is based upon the belief in karma: every action we do will come back to us later as a consequence. So if we harm someone else, that deed will return to us thanks to the universal law of cause and effect. We cannot possibly commit any action without reaping the consequences upon ourselves. In this way, we avoid violence as a form of self-protection. This belief is somewhat in contrast with the Western view of violence. We protect ourselves, our families, our possessions and our ideals with violence if necessary. Violence is justifiable in self-defense. Violence can even be morally encouraged if we think that the loss of 10 lives will save a million. Admittedly, this is complicated. It can be difficult to assess what we believe as individuals. But it is worth considering the varying viewpoints and their consequences. The yogic view, which avoids violence at literally all costs, has the possible repercussion of allowing the dominance of others who are willing to resort to violence. If I will not fight back, I will probably lose every battle I fight with someone who will. On the other hand, the self-preserving view, that permits violence in self-defense, encourages a highly-developed sense of identity and ego. It also encourages strenuous adherence to systems of belief, which can develop into violent action to defend those beliefs. TRUTH A yogic ideal with far less complexity is the idea of honesty or truth. To our knowledge, every culture encourages honesty. Our parents warned us from a young age, "Tell the truth! Don't lie!" The reasons why we choose honesty or lying are far more interesting. Most interesting are our reasons for lying. Ask yourself: "Why do I lie? When is it justified to avoid the truth or misrepresent it?" The reasons for lying can be distilled down to one word: power. We lie because it gives us power. When my boss asks why I'm late, I lie and say I got a flat tire. I have more power than I would if I told her the truth, which is that I slept through my alarm. Lying forces my boss to accept my version of reality, which allows me to dictate the consequences. Of course, this only works if my boss doesn't have access to other sources for the story. In that case, I don't have power over her version of reality. This is the great lesson of lying. It is only as powerful as its ability to bend the listener's view of reality. When someone lies to us and we believe it, we are completely under their power. However, if they lie to us and we do not believe it, they have no power over us whatsoever. Why does yoga encourage truth? Because it aligns us with reality. Every time we lie, we fracture ourselves from reality. If it is 2 o'clock but I say it is 10 o'clock, I have essentially separated myself from fact. I have constructed a small alternate universe and isolated myself from the real one. If we lie frequently, we remove ourselves from reality and increasingly exist in a bubble of our own making. Yoga's goal is to reverse this process and gradually place us firmly and directly in reality. Not our own thoughts or beliefs, but reality itself. Try it for yourself. Next time you are tempted to tell a lie, no matter how small, tell the truth instead. Your individual sense of power will decrease, but this is only a false sense that is driven by the ego. What improves is your connection to truth, which actually makes you immensely more powerful. IN CONCLUSION The way in which we relate to the world has real consequences. This includes how we think of ourselves and our beliefs. Are we willing to fight for them? Who are we fighting and why? Is violence justified by its outcome? Does the end justify the means? Will we lie to protect our identity, possessions or power? Will we accept the lies of others to do the same? Yogic philosophy answers these questions in specific ways. But that is not terribly important here. What is important is that we consider these questions. And realize that how we answer them will have real-world impact. In a normal year we leap into action in September, traveling all over the US and Canada to visit studios and lead workshops. We spend a weekend in each city so that the yogis there can take real time immersed in study and practice. But this is not a normal year. Yoga studios are either closed completely, operating with severely limited schedules and capacity, online, or fighting for their lives as a business. Which of course means that yoga practitioners are left wondering how to practice and how to make progress.

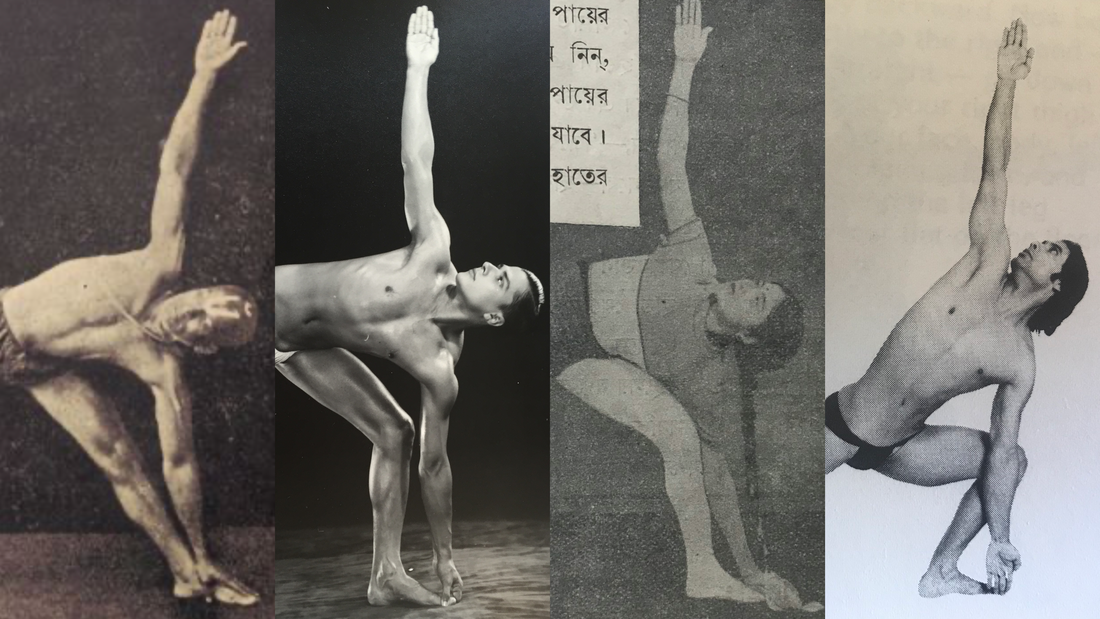

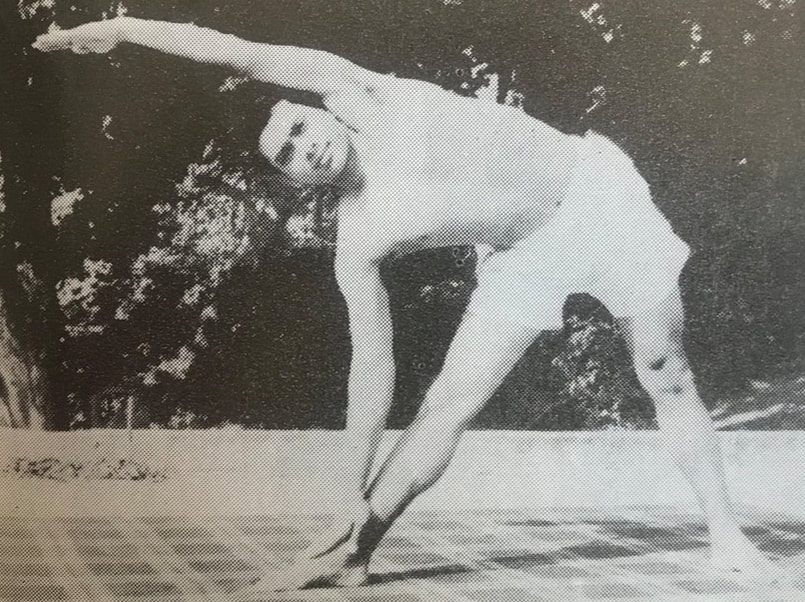

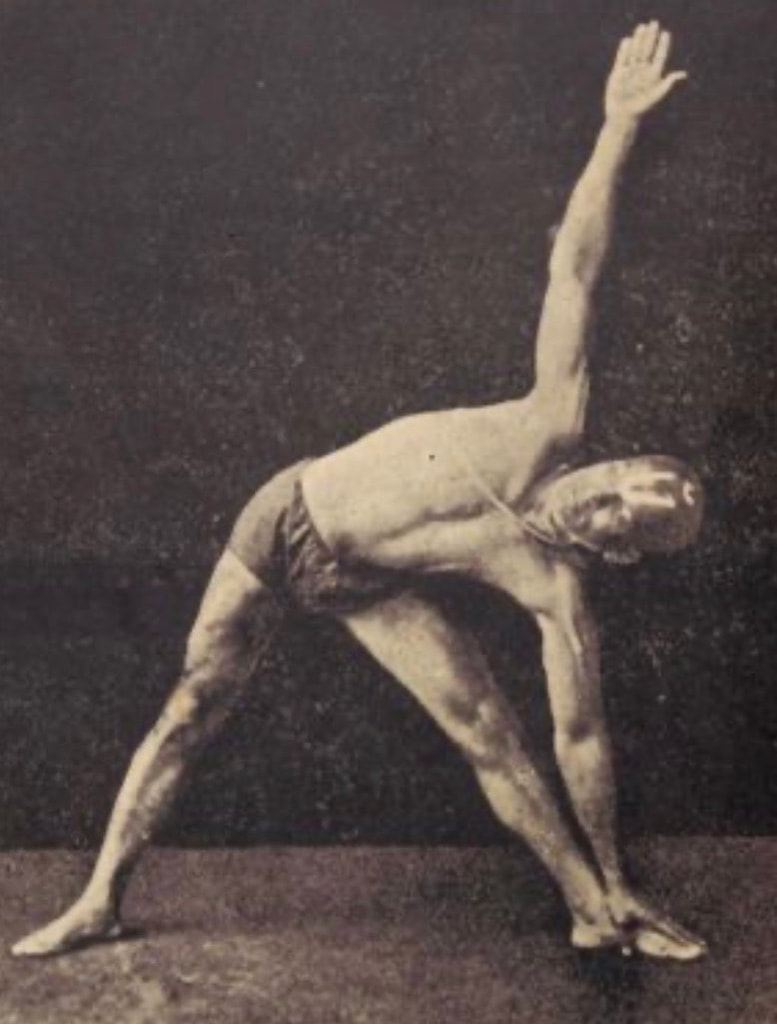

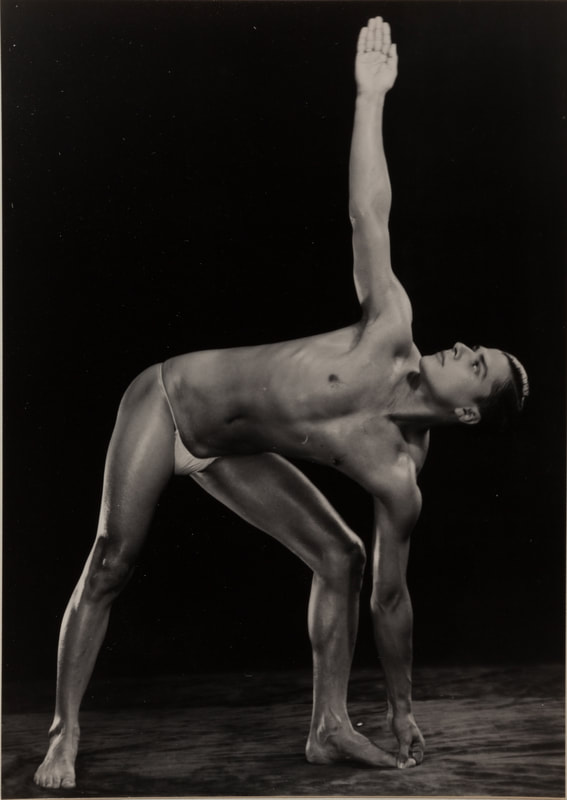

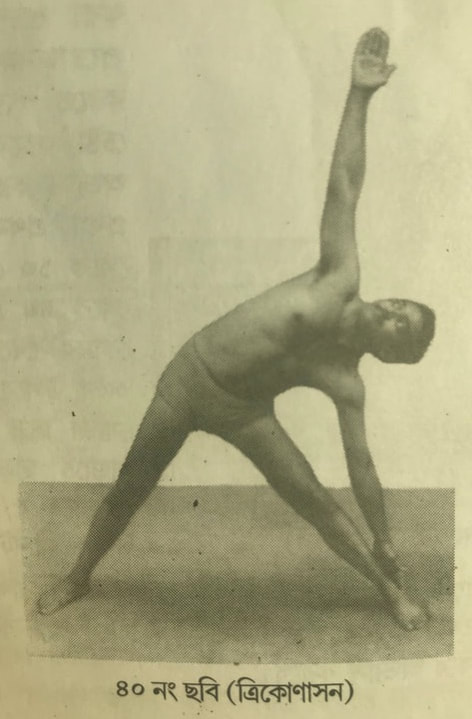

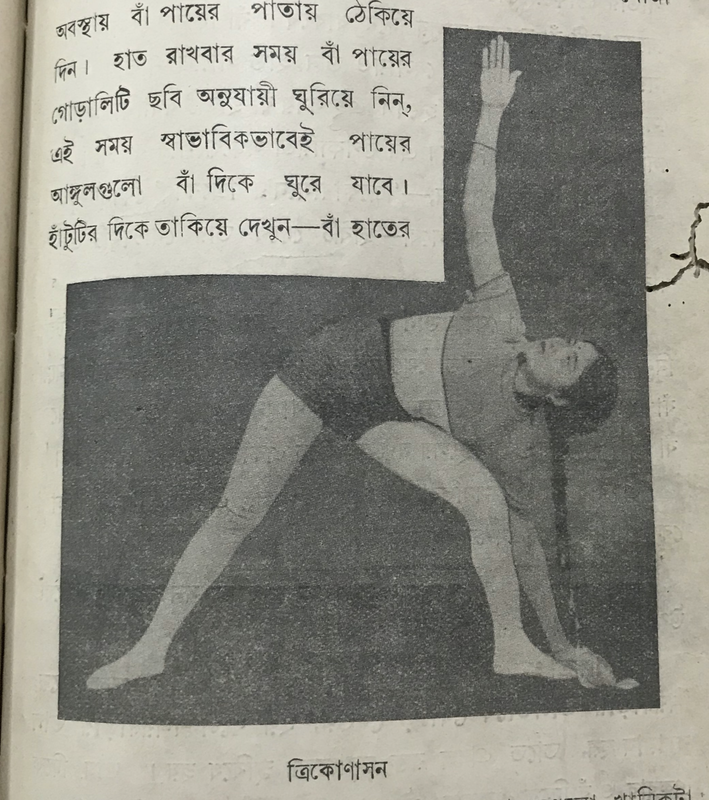

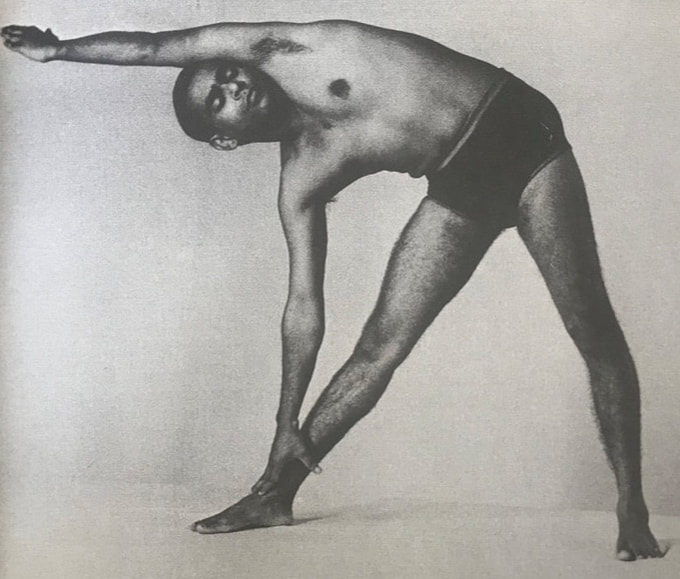

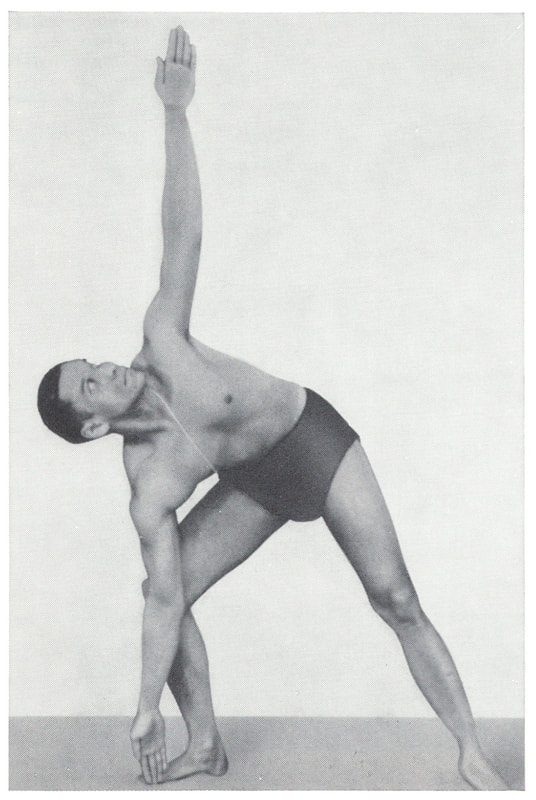

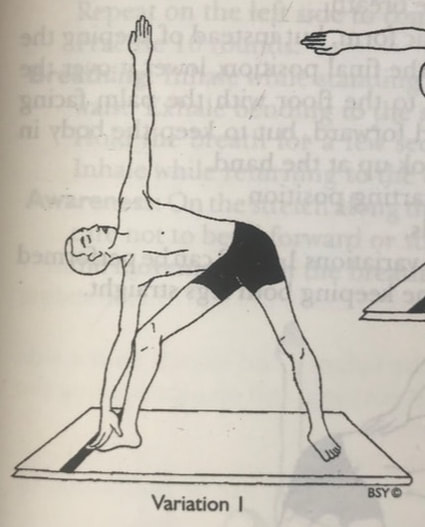

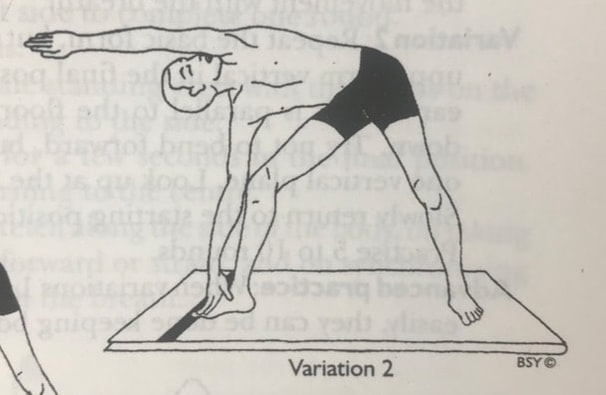

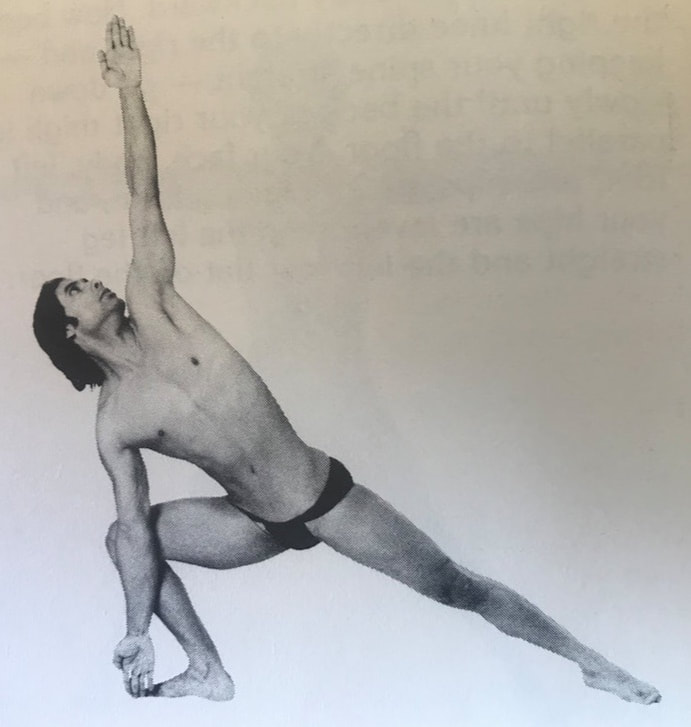

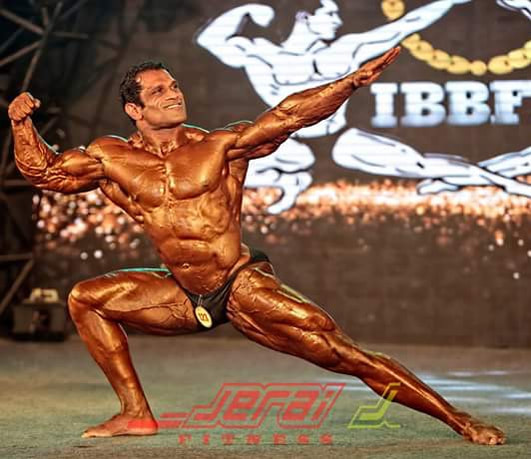

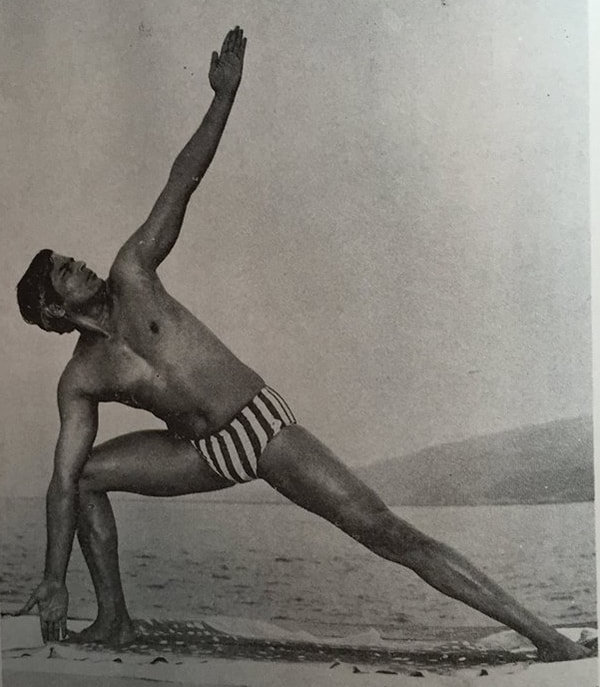

This September we will run two four-week workshop series online. Our goal is to enable yogis to study, learn and practice as they would if they attended an in-person workshop. When we are in-person we usually practice for 6-8 hours per day. But that would be pretty terrible in an online setting, so we will break it up into two-hour chunks. One each Saturday, every Saturday in September. BREATHING & PRANAYAMA The first workshop series is about pranayama. More people ask us about this than anything else. It is a natural and important progression from posture practice, since once we can control the body, the breath is next. In two-hour sessions we will walk you through how the body breathes, the effect it has on the nervous systems and body chemistry, and what it means for yogic practice. Part of the sessions will be in lecture format and part will be practicing these ideas and techniques. Each week you will get a little homework practice that will take 10-15 minutes per day. In this way you will build your understanding and experience with pranayama, yogic breath control. By the end of the month, you will have the knowledge and skills to make progress on your own for 1-2 years. More details about the schedule and sign-up are here. BUILDING BALANCE The second series is a class series about Balance. We will lead you through 90-minute classes designed to build the strength, awareness, control and concentration that are needed to balance well. No lecture portion for these classes, as they are purely experiential. More details about the schedule and sign-up are here. BOTH Of course, you can sign up for both. The two are intended to work together and complement each other. Our goal with these is exactly the same as when we travel to meet you in-person: to provide the opportunity to learn and deepen your practice. You may be a dedicated daily practitioner or someone who goes in fits and starts. Our hope is to inspire you in your practice and give you the knowledge and tools to make progress! Triangle Posture - Trikonasana - is a relatively new addition to the physical practices of yoga. Along with most other standing postures, Triangle is absent from the texts of Hathayoga. It makes an appearance in the 1920-30s as yoga in India is becoming more exercise oriented. This makes it strange to speak of something like a 'traditional' Triangle Posture, since its use in yoga has yet to hit the hundred-year mark. Below we have traced the transmission and progression of Triangle Posture through the last century, especially in Kolkata and the Ghosh Lineage. Among the students of Ghosh, it was consistently practiced for decades since its earliest iteration in 1938 with Buddha Bose. In the 1960s the posture disappears before being reborn as a deep sideways lunge. This is seen in Bikram Choudhury and Jibananda Ghosh but nowhere in Kolkata itself. It seems that this is an influence from bodybuilding, though it is unclear exactly when, where and why the change occurred.

It would appear that the evolution of Triangle Posture into a deep sideways lunge shows influence from bodybuilding. It is unclear if this is an innovation of Choudhury himself, or if it occurred more generally around the time when he was learning. Evidence of bodybuilding's influence on Choudhury's instruction is visible in other places as well, including the instruction to 'lock the knee'.

Triangle Posture itself is a relatively new addition to 'yoga' practice, probably being adopted in the 1920-30s along with other standing, exercise-based positions and movements. After its adoption as a yogic asana, it was relatively stable in its practice for decades. In the Ghosh lineage, it was done with one knee slightly bent, the torso parallel to the ground, and one hand touching the foot. In the 1970s, the posture underwent a significant change, perhaps being reinvented entirely, turning into a deep sideways lunge that resembles a bodybuilder's pose. This version is taught by Choudhury and his students.

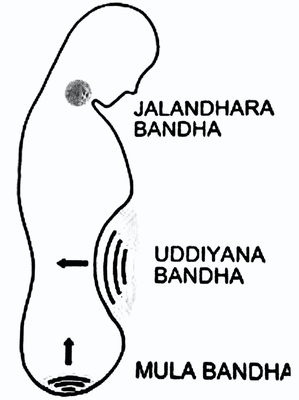

For another posture that underwent significant development and change in the 1960-70s, see the Standing Bow Posture. (Thanks to Jerome Armstrong for the insight about bodybuilders.) Mula bandha is a somewhat common technique in modern yoga. It is generally accepted that this technique, which means 'root lock', is a contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor. Some interpret this to be the perineum, the anus, or a combination of the muscles in the pelvis. The anatomical specifics of how and when to do mula bandha are not the goal of this article. Today we are looking at where the practice comes from, and perhaps why it was developed. The instruction of mula bandha dates back to the early days of Hathayoga, around the 12-13th centuries CE. At this time, Hathayoga was gradually forming out of the tantric beliefs of Buddhism and Shaivism. Alchemy, the attempt to forge new substances, was widely accepted, and the spiritual seekers began practicing an 'inner alchemy' where the magic happens inside the body of the yogi. According to this alchemical belief, the inner elements of a person could be forged to create immortality, divinity or great power. As Shaivism (the worship of Shiva) became more prominent in Hathayogic teaching, the concept was related specifically to the awakening of kundalini, a latent power of pure consciousness. The way that kundalini is awakened is by manipulating the 'winds' of the body, some of which naturally go up while others go down. In Hathayoga, mula bandha is specifically intended to take the downward-moving 'wind', called apana, and push it upward. Once the apana wind is turned upward, it is fanned with the abdomen to heat it. Then it combines with the upward wind, called prana. The combination creates an inferno that awakens and raises kundalini. Below is an excerpt from the Hathapradipika, perhaps the best known text on Hathayoga:

As you can see, mula bandha is specifically intended to turn apana upward, where a whole series of events follows. This description of mula bandha is present in almost all the texts of Hathayoga. Here is one other, from the Goraksasataka, translated by James Mallinson. I include it because it is pretty elaborate and well-explained:

This explanation continues to the modern day, though it is rarely incorporated in common yoga posture classes that remove esoteric or spiritual overtones. For obvious reasons, a simple muscular contraction is far easier to teach and understand than a detailed metaphysical system of bodily winds and latent spiritual energy. Nonetheless, Swami Sivananda and his students like Vishnudevananda explain mula bandha similar to the older Hathayogic way. Iyengar, in Light On Yoga, foregoes the apana-kundalini approach and explains mula bandha a little differently. He initially explains the bandhas as closing off "safety valves", which is reminiscent of the old way. But he goes on to interpret the term mula bandha as follows: mula means 'source', and bandha is 'restraint'. So mula bandha is the restraint of the mind, intellect and ego. This recalls Patanjali's famous definition of yoga at the beginning of the Yoga Sutras. Here is what Iyengar writes in Light On Yoga:

We don't think it's a stretch to say that this is a reinterpretation of the meaning of mula bandha. Separately, in modern practice and teaching mula bandha is sometimes taught as a physically stabilizing technique, again quite different from its original iteration.

What does it all mean? Like so many things in yoga, the purpose of the practices can change so that they become unrecognizable. Does that make them less effective, useful or valuable? Perhaps. We think it is worth asking ourselves why we do what we do. What are the underlying reasons? Personally speaking, we do not hold the belief that our bodies are populated by 'winds', as was apparently the belief for some time during the development of Hathayoga. We attribute our 'digestive fire' not to actual fire but to hydrochloric acid in the stomach. And we attribute urination and excretion not to downward-moving apana wind but to peristaltic movement of the intestines and contraction of the sphincters. Do these beliefs make something like mula bandha anachronistic? We think that they do. Over the last few months I’ve been compiling materials to research the forgotten women of yoga. Through work in Kolkata, I came to know of a few names of women, some quite famous, who today are completely forgotten. The questions started piling up— why do so many women do yoga when it was thrust into the modern age largely (at least publicly) by men.

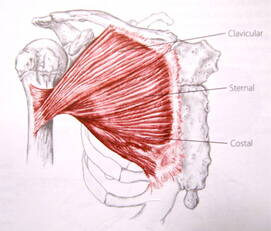

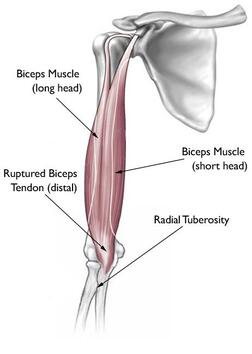

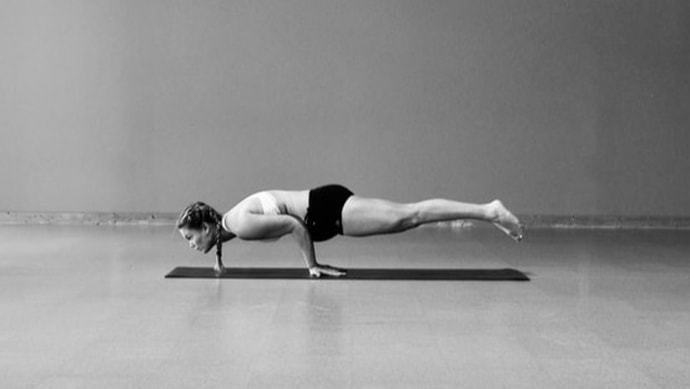

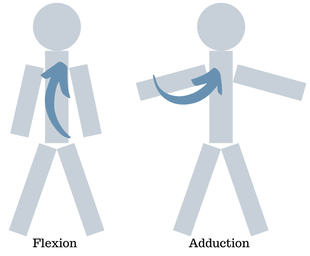

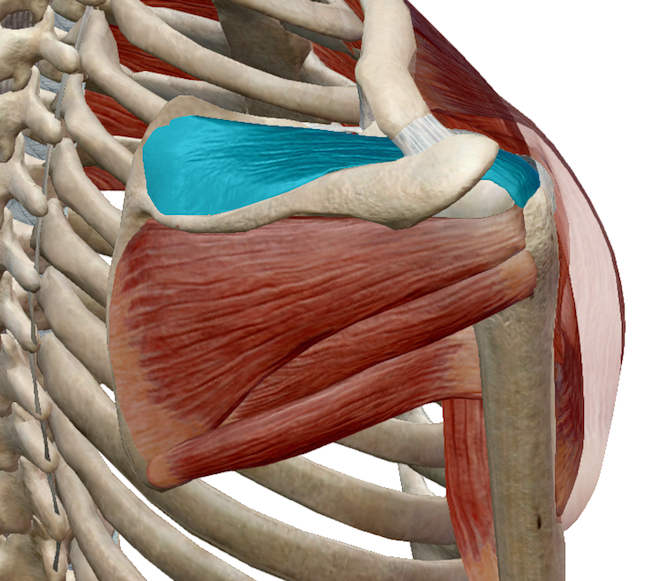

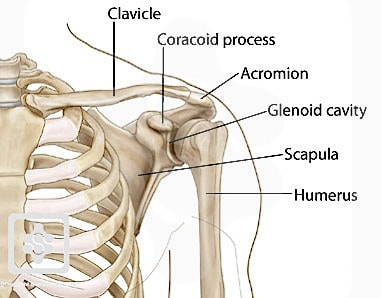

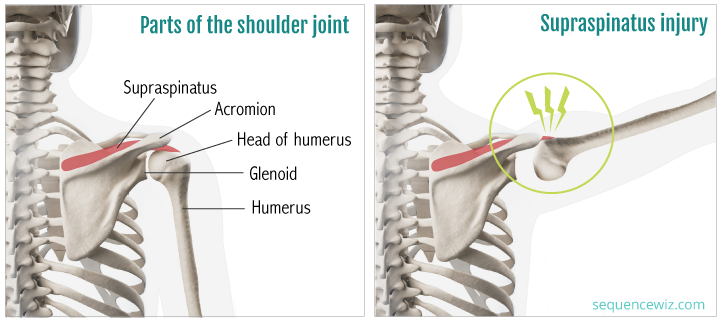

Through gathering texts and doing interviews, the layers of complexity grew. One unanticipated layer is the talk of beauty when it comes to women and yoga. This isn't found in posture manuals for men, and isn’t about “radiance” or something that could be referenced in Haṭha texts. This is talk of things like “perfect breasts” and “thin waists”. This made me think of my own journey in the yoga studio so far. The "no food is good food" was certainly a part of the community. I remember being complimented the most in class when I was incredibly sick with pneumonia and hadn't been able to keep any food but applesauce down. Around that same time I was also injured. My hamstring was tearing but I was locking out my standing bow. (Worth it? No.) Since then I stopped wanting to be injured and took up weight training. When my new trainer gave me 15 pushups as a warm up I balked! I couldn’t do one, yet I was one of the strongest at my yoga studio. I have since gained 15lbs. And with it, the strength to run many miles, move hundreds of pounds, do pull-ups, (more than 15) pushups and most importantly, have the strength to stay injury free. Since talking about injuries in yoga studios around the world, we've gotten a variety of responses. Some burst into tears and ask, “So it shouldn’t hurt? I’ve spent a decade thinking it was supposed to.” Some just shake their heads, acknowledge how obvious it is that a "healing" practice shouldn’t injure the body. Others though, respond with the predictable, yet disappointing response of, “Well I’m not injured. You weren’t doing it right.” Denial is powerful. All of this combined has me thinking. Are we trying to be healthy or beautiful? Who is deciding this? Do we actually know what we’re doing? This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. Last month we wrote about the common shoulder injury Shoulder Impingement. The other common injury to the shoulder happens in the front, where the short head of the biceps muscle attaches to the shoulder blade, a biceps tendon strain. This injury is most common in Ashtanga Vinyasa and subsequent 'flowing' yoga styles that incorporate a lot of Sun Salutations and chaturangas. The shoulder can't do this action very well, and the biceps become strained before too long.  Pectoralis major ("pec") Pectoralis major ("pec") To understand this injury, we have to talk about shoulder mechanics and the muscles that move the arm. PECTORALIS MAJOR & ADDUCTION One of the biggest and most powerful muscles of the shoulder is the pectoralis major, commonly known as the 'pecs' or just the 'chest muscle', pictured to the left. It connects the arm (humerus) directly to the middle of the chest. Its main function is to pull the arm toward the chest in an action called adduction. Try it: hold your arm out to the side (as pictured below, labeled adduction), then bring your arm toward the center, so you end up with your arm pointing forward. As you do this, you will feel your 'pec' engage. When you apply this motion to something like a pushup, the arms need to be away from the body, so the pushup motion will be pulling the arm inward toward the chest. Simply put, this means keeping your elbows away from the body. This is the safest way to do any pushup motion.  BICEPS & FLEXION In contrast, if we start with our arms down by the sides and lift them up until they point forward, this is called flexion (pictured above, labeled flexion). When we lift the arm like this, the pec doesn't get activated much, so the work is done by much smaller muscles like the anterior deltoid (the front of the shoulder cap) and the biceps. The biceps cross two joints; they bend the elbow and also flex the shoulder. But they don't have the power to move the body's entire weight. When we do pushups or chaturangas with the elbows close to the sides of the body, we are essentially moving the shoulder in flexion. This is not a powerful nor particularly healthy way to move so much weight. When we do this repeatedly, the bicep tendon (usually the short head at the attachment with the coracoid process of the shoulder blade) will often be damaged. This manifests as pain or soreness in the front of the shoulder. There is a common belief that keeping the elbows close to the body uses the triceps more than if the elbows were wider. This is not true for the simple reason that the triceps straighten the elbow, and the elbow is doing a similar action in both versions. The big impact is on the shoulder and what muscle group you use when doing a pushup or chaturanga motion. IN CONCLUSION There is nothing inherently wrong with keeping the elbows close to the body and flexing the shoulder. The problems arise when we do this with our entire body weight and do it repetitively. This is how injury usually happens. Consider making the elbows wider, which will strengthen the huge pectoralis major muscle as well as be safer for the smaller muscles of the shoulder. Happy, healthy practicing! This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. Two common injuries in yoga happen in the shoulder. One is in the front of the shoulder---the biceps tendon---which we will address next time. The other is in the top of the shoulder, called impingement. It happens when the arm lifts up high; the arm bone can bump against the edge of the shoulder blade, called the acromion, and damage the tendon there.

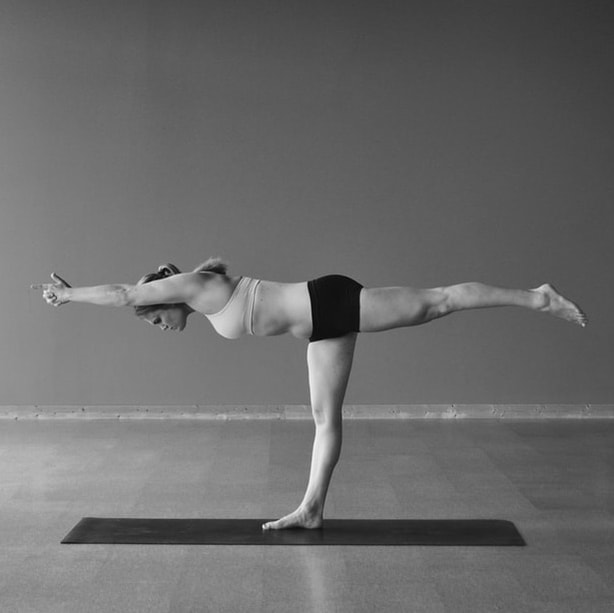

HOW THIS CAN HAPPEN In yoga, this happens most often when we force the arms overhead. Think of any time you link your hands together and then try to straighten your arms using force. As pictured below, it happens in Half Moon Backbend, Half Moon Sidebend, Balancing Stick and Half Tortoise, among others. (It also happens in Downward Facing Dog.) When we force our arms to straighten overhead, we usually use the triceps, a muscle mainly of the elbow, to compel movement in the shoulder. This is where we get into trouble and impingement can happen. You will feel a 'pinching' sensation in the top and outside of your shoulder. This is the bones bumping into each other, damaging the soft tissue. If the shoulders become injured this way, they will be painful whenever lifting the arms sideways, and the breathing exercise pictured at the top will cause pain.  HOW TO HELP The simplest and most effective way to avoid this injury is to not link your hands together. Just place them side by side without interlacing the fingers. Interlacing the fingers and forcing the arms straight overhead is the easiest way to create the injury. Or don't lift your arms overhead (pictured below left). Most postures can be done quite effectively without the arms overhead. All of the positions pictured above don't require the arms to get the primary benefit. Alternatively, you can lift your arms forward and up (pictured below) instead of out to the side. This will help the shoulder blades move into the proper position and keep the shoulders healthy. In the breathing exercise, pictured at the top, you can keep your elbows lower, not lifting them higher than the shoulders. This will prevent further irritation of this area. To build strength in the area, postures like Full Locust will help (pictured below right). By pulling the shoulders back and together, we build strength in the back of the shoulder to help stabilize and balance the joint. CONCLUSION

The moral of the story is that we should be aware and careful when lifting the arms overhead, especially if we are gripping the hands together and straightening with force. If there is a 'pinching' sensation in the top of the shoulder, back off immediately. There is nothing there to 'stretch', and it is likely that we are impinging our supraspinatus tendon. Try adjusting your approach to the posture and using your shoulders a little differently. Happy, healthy practicing. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed