|

Last week we asked you, our readers, for questions that you'd like addressed. We received many great inquiries, and today we will address one:

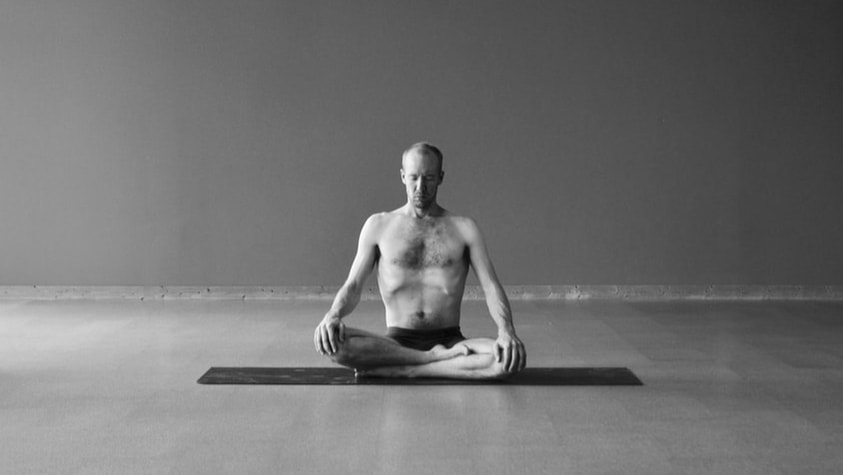

"Can you talk about the importance of stillness in yoga practice?" As we consider the importance or lack thereof of stillness, it is vital to consider the root question of any undertaking: what is the purpose? Before reading on, it is worth taking a moment to consider the purpose of your yoga practice. The form of your practice should serve its function, meaning that it should accomplish whatever it is that you are trying to achieve. This can be complicated when talking about yoga, because it has changed a lot over hundreds of years. TWO STYLES Stillness can be confusing and even controversial in today's Western yoga world. The majority of what is practiced as yoga today includes abundant movement, often referred to as "flow." Various bodily positions are fluidly linked together and transitioned between, with lots of Sun Salutes, a calisthenic exercise that incorporates regular breathing with stretching, a push-up-like movement and some spinal bending. The Sun Salute (Surya Namaskara) became popular in India in the 1920s. A contrasting style focuses on positions held in stillness, anywhere from 10 seconds to several minutes. In the past decade or so, it has become fashionable to refer to any stillness-based method as hatha yoga, presumably to separate it from the movement-based vinyasa methods described above. DIFFERENT YOGAS For the past hundred years or so, calisthenics, gymnastics, acrobatics and contortion have taken the name of yoga. This is why so much "yoga" in the West includes movement, strength, jumping, deep stretching, rhythmic breathing, getting the heart rate up, sweating, etc. Calisthenics and exercise have been known to improve physical and mental health, and it is no surprise that yoga practices have veered in this direction as our culture puts more and more value on fitness. But these tendencies--movement, health and fitness--are new to the yoga world. CLASSICAL YOGA The earliest extant texts on yoga, including the Upanishads, the Mahabharata and the Yoga Sutras, describe a practice of mental concentration, turning the senses, mind and intellect toward the inner self. This practice doesn't include moving the body in any particular position, other than holding it “steady like a pillar and motionless like a mountain. Then it can be said that they are practicing yoga.” (Mahabharata 12.294.15) According to these texts, stillness of the body is a prerequisite for yoga practice. If the body is moving, the senses are stimulated, including the sense of touch and sight to enable coordination and balance. The senses draw the mind outward, preventing it from turning inward in anything that could be called yoga practice. According to the earliest texts, yoga is not a physical practice but a mental one. So focusing on what we are doing with the body can be misleading, lest we think that holding the body in stillness equals practicing yoga. But the body must be held "as motionless as a rock” (Mahabharata 12.294.14) for the true practices of yoga--the mental elements--to be done. WHAT ARE YOU PRACTICING? Over the past 100 years or so, increasingly physical activities have been labeled "yoga," bringing us to the present day, when yoga has the connotation of gentle exercise, stretching and perhaps some spiritual elements. The physical focus has become more central, and the mental/spiritual focus has diminished greatly. If you want to improve your flexibility and reduce your stress, the low-impact exercises that are now known as yoga will be helpful. If you want to increase your cardiovascular endurance, you should do longer, more repetitive exercise like running or swimming. Even the most vigorous yoga practices only give a fraction of the cardiovascular benefit of running. If you want to lose weight, check what and when you are eating, your stress and sleep. If you want to understand the nature of your mind, being and who you are, the meditative practices of yoga are for you. In the end, it doesn't much matter what you call the practices, it just matters what the practices accomplish. So whether you call it yoga or something else, try to choose the right practices for your goals.

7 Comments

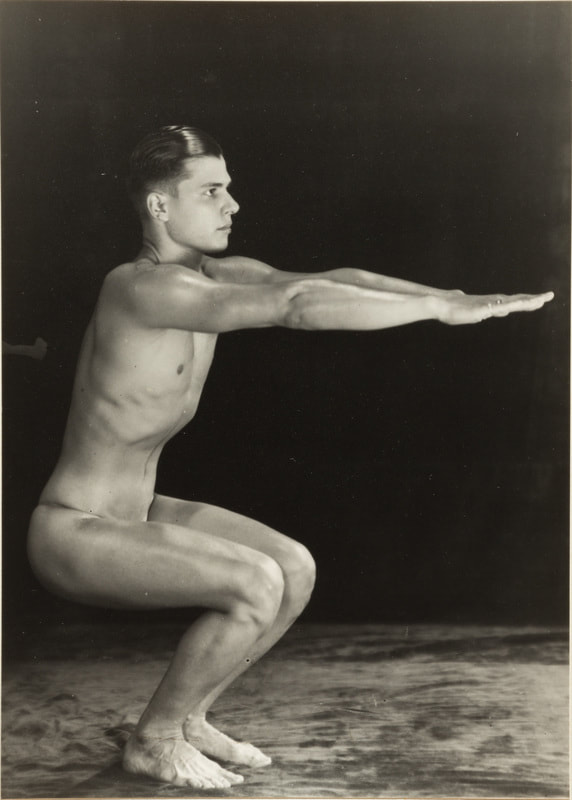

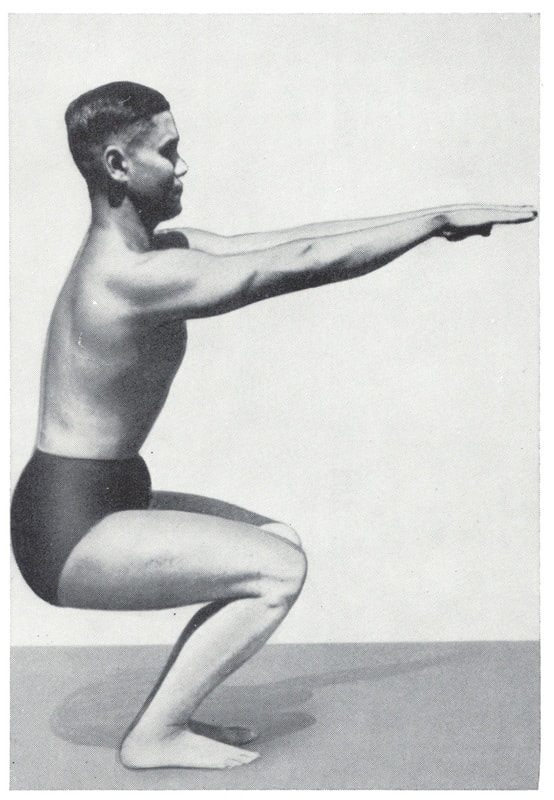

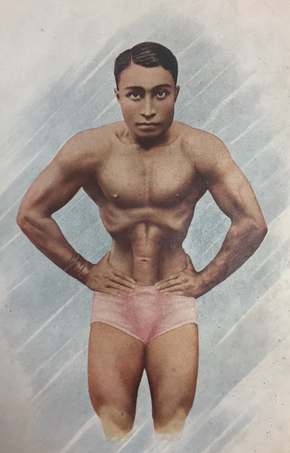

Postura de la Silla, también llamada postura incómoda, es una posición fundamental para el cuerpo. Es una posición segura para principiantes y desafiante para yogis con más experiencia. Ha sido malentendida en los últimos años, haciéndola como en una sentadilla con la espalda curvada, que se brinca muchos elementos importantes de la posición. La Columna Vertebral La columna vertebral en la postura de La Silla debe ser derecha y los más vertical posible. A tu izquierda verás fotografías de 3 yogis en esta tradición: Buddha Bose (arriba a tu izquierda) en 1939, Gouri Shankar Mukerji (en el centro a tu izquierda). Bikram Choudhury (abajo) en los 70s. Mira sus columnas vertebrales. Son derechas (con la forma natural curvada), y bastante altas. Ninguno de ellos se está inclinando hacia delante, sacando sus traseros hacia afuera detrás de ellos, o curveando sus espaldas para levantar sus pechos y hombros. También es interesante notar en la fotografía – la mujer a la derecha de la foto está haciendo la postura incorrectamente, con su trasero hacia afuera y con la espalda baja curvada. Nota qué tan diferente se ve su postura a la de Bikram (Bikram es el segundo de la derecha en la foto), y también que inestable y no integrada esta. Esta es la manera como muchos enseñan esta postura ahora. Los Pies Bose (arribe a la izquierda) y Mukerji (centro a la izquierda) tienen sus piernas y pies juntos, con los dedos de los pies un poco más abiertos que los talones. Esto es diferente a como muchos enseñan la postura hoy, motivando a que las rodillas y los talones estén separados a la medida de las caderas, y los pies metidos un poquito hacia dentro. Lo Que Se Ha Perdido De alguna manera esta postura se ha vuelto en “piernas separadas, dedos adentro, trasero hacia atrás, columna curvada (foto a la derecha)”, todo lo contrario a la manera en que esta postura se practicaba por estos estudiantes expertos de Ghosh. El culpable saca sus caderas y trasero hacia atrás para simular la profundidad en la postura. Sacando las caderas hacia atrás dobla las rodillas, pero obliga a que la parte superior del cuerpo se incline hacia adelante para contrabalancear. Entonces para corregir la significante inclinación hacia adelante, el practicante moderno arquea la columna vertebral para tratar de traer los hombros hacia atrás sobre las caderas. Ejecutando la postura de esta manera desacopla tanto como los músculos del glúteo máximo (trasero) y los músculos abdominales. Estos dos grupos enormes de músculos generalmente sufren en nuestro estilo de vida occidental, con tanto estar sentado uno en sillas. Tiene sentido que estamos débiles, y que la postura se ha alterado para compensar por nuestra debilidad. Como Cambiar Para ejecutar la postura apropiadamente, como se ha hecho desde Bose a Choudhury, los glúteos y las abdominales se deben comprometer para inclinar la pelvis hacia atrás. Esto aplanara la columna vertebral. El peso se mueve para atrás significativamente, lo que significa que los tobillos deben doblarse para empujar las rodillas hacia adelante. Fíjate en la posición de las rodillas de Bose, Mukerji y Choudhury. Todas están significativamente delante de los tobillos. Aprendiendo a practicar la postura de La Silla de esta manera puede ser retador, especialmente cuando lo hemos hecho incorrectamente por tanto tiempo. Empieza despacio. Dobla las rodillas solo un poco, y empújalas hacia adelante. En vez de enfocarte a que tus caderas se vayan hacia atrás, dobla tus rodillas y empújalas hacia adelante. Cada vez que sientas que la parte posterior de tu cuerpo se incline hacia delante, endereza tus piernas un poquito, levántate, y otra vez empuja tus rodillas hacia adelante. Evita que tu columna vertebral se arquee. Trata de mantener la espalda plana. Te darás cuenta de que tus músculos abdominales necesitan estar bastante apretados. Practicando de esta manera integrará a los músculos de tu pelvis y tu columna vertebral, fortaleciendo tus tobillos y mejorando tu balance significativamente. As we mentioned in the last entry, we are in Tokyo this week with the family of Karuna and Jibananda Ghosh. Today, their son Bubai wrote individual charts for us and led us through the regimen.

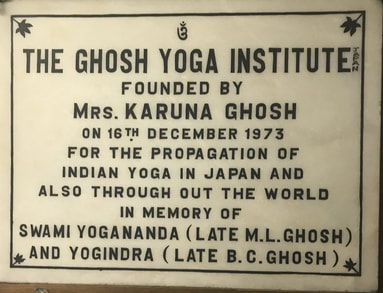

Yoga practice in this tradition--passed down from Bishnu Charan Ghosh and his students--is individual. It is hard to stress that enough. Each student gets one-on-one attention from the teacher, who assesses the student's strengths, weaknesses, illness, history and goals. The teacher then devises a routine of exercises unique to the student. The concept of a "yoga class" where many students perform the same routine is practically unheard of in this tradition, just as the idea of a yoga prescription is unheard of in the West. In making our charts, Bubai draws from a system of about 40 asanas, most of which Western yogis would be familiar with. The important element is not necessarily knowing more postures, but knowing which ones to use and when. In addition to the asanas, there are about a dozen "Exercises" that are done in movement, like calisthenics. These are generally done at the beginning of the session to warm the body and prepare it for the asanas. After many questions about our health, family history, goals, taking our blood pressure and pulse, and doing a small battery of tests to check brain function (luckily we both passed!), the prescriptions are drawn up. Both Ida and I are prescribed 2-3 exercises to warm up, followed by about 8 asanas and kapalbhati (blowing) breathing. Each element is done two or three times, punctuated by a few deep breaths and a rest in shavasana (which, like all Bengalis, he calls savasana). Bubai hovers over us as we do the postures, making corrections and explaining why things are done in a certain way. We end with a brief meditation, a focused set of thoughts that he gives us. Then a rest and we are done. It has taken about 45 minutes. It is not strenuous or sweaty or exhausting. We are calm and focused and ready to continue with the day. This week we are in Tokyo, Japan, connecting with part of the Ghosh lineage. Namely, the family of Karuna and Jibananda Ghosh, and their son Bubai.

Karuna was the youngest daughter of Bishnu Ghosh, and after Bishnu's death in 1970, she and her husband Jibananda adopted Bishnu's dream of establishing a yoga school in Japan. They came to Tokyo and founded the Ghosh Yoga Institute Japan. Ever since, they have been instructing prescriptive and therapeutic yoga from a humble room here. The yoga has always been one on one, with each student getting unique attention and instruction from the teacher. We have known about the Tokyo family only vaguely, aware that Bishnu traveled here with performance troupes, doing feats of strength and contortion. There are widespread videos of some of these performances. We knew that he had set up a yoga school and that perhaps Buddha Bose and his sons were involved in the early days. Thanks to Jerome Armstrong's new book Calcutta Yoga, we were aware that a handful of young teachers were sent to Tokyo as holdovers while a more permanent teaching solution was found. Among these young teachers was Bikram Choudhury, who passed through Tokyo before eventually settling in the USA. But we have been ignorant of the depth of history and knowledge here. This limb of the Ghosh family has committed themselves to yoga for 50 years. They established and fostered a school and community here, ambassadors of yoga to a new culture. Karuna Ghosh died in 2006, partly due to old internal damage from carrying heavy objects like elephants on her chest. Jibananda still runs the Institute. Their son Bubai is a businessman who also teaches yoga, prescribing "charts" for his students. He has started a separate little school in a more modern part of Tokyo. Bubai met us as we disembarked from the plane. He fluently speaks English, Japanese and Bengali. He will generously spend the next 3 days introducing us to his family, Tokyo and the yoga history here. The ultimate goal of yoga practice is understanding the true nature of who we are. This can seem abstract--how could we possibly be anything other that who we are?--but it has to do with the ego and the mind's creation of an identity. To realize our true self we strip away the mental constructions and are left only with our deepest "self."

The first step in this process is the body, since we identity our "self" with the body and its actions. So we teach ourselves that our body and its actions are malleable and impermanent. Since they are being controlled by a deeper power, they cannot possibly be the truest form of the self. We do this by controlling the body with yoga postures and alternating with stillness. This alternation between effort and rest, action and non-action, the posture and not the posture, gradually teaches us that even when we are not doing anything we are still ourselves. Again, this may seem obvious or abstract, but you may be surprised how hard it is to do nothing. Our minds and bodies are constantly drawn toward action, as if their very existence relied upon it. When we force the body to be completely still we can face something of an existential crisis, fearing that we will cease to exist of we cease to act. This is why alternating action and inaction--the posture and not the posture--is so profound. Breathing is central to yogic practice. Controlling the breath is far more powerful than controlling the body. It has physical, nervous and mental impacts. Here are three reasons to do breathing practices.

1. IMPROVE POSTURE AND DIGESTION By strengthening the two systems of breathing--the chest and abdomen--many muscles are strengthened. The muscles of the ribs and spine help hold the torso upright, improving posture. The muscles of the abdomen support the lower spine and massage the intestines with each breath. 2. CALM DOWN OR FOCUS The two parts of breath impact the nervous system, which controls how calm or focused we are. Breathing into the abdomen stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system, lowering our heart rate and settling the body and mind. Breathing into the chest stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, heightening our awareness and attention. 3. MIND CONTROL Controlling the breath requires communication between two distinct parts of the brain, one which is very old and one which is newer. When we breathe consciously, the coordination between these two parts creates intense focus in the mind. It is a relatively simple way to control our own minds! When we step in front of a class of students to teach, it is natural for the ego to grow. After all, the teacher is one person while the class is many people. The teacher knows about the practices, history and purpose while the class is learning. The teacher controls the practice while the students follow her lead. All attention is directed toward the teacher. It is normal for this to create an inflated sense of importance. But the teacher and student are two parts of a larger system of learning, and they need to work together to be successful. As much as the student must serve the teacher to learn and progress, the teacher must also serve the student. The two are an inextricable team. In the Sivananda tradition, there is a little invocation that precedes every class, describing this union between the teacher and student, and how they must work together in harmony. May we (the teacher and the student) be protected together, May we be nourished together, May we both work together with great energy, May our study be enlightening and not give rise to hostility. ...AND NOT GIVE RISE TO HOSTILITY

I especially like the last line: "May our study be enlightening and not give rise to hostility." It is pretty easy for the teacher to resent students who do not listen to instruction. These students make the teacher feel powerless and worthless, so the teacher dislikes them. Hostility is born. It is also easy for the student to resent the teacher. The student may be struggling to understand or progress. Or he may have conflicting experience or knowledge that makes him resist the new teachings. Or he may just be having a bad day. As the teacher pushes the student to conform, the student grows frustrated with the teacher. More hostility is born. BETTER COMMUNICATION It is important not only to avoid this hostility, but to actively promote collaboration and communication between teacher and student. We are all in it together. It is a symbiotic relationship, as the student can not exist without the teacher and the teacher can not exist without the student. A student must always be able to ask questions. Surprisingly, the questions will help the teacher as much as the student. They reveal the student's understanding--where he gets it and where he struggles. This is the single greatest tool that a teacher can use to serve her students. Today, July 9th, we celebrate the life and work of Sri Bishnu Charan Ghosh! So many around the world have benefited from his contributions to fitness, yoga and his dedication to teaching. We are ever grateful for his work and may we all remember him today and always.

In honor of his life, here is an excerpt from the new book Calcutta Yoga Jerome Armstrong: Bishnu naturally took to the stage. “I showed my muscle move ments and I can still hear the resounding claps I received. The people shouted from the gallery – ‘it was worth the eight annas spent.’” Once he had “performed the muscle control” exercises of nauli and uddiyana under “gas lights shown from below with reflectors,” he came on stage “dressed like a clown” and took part in all the performances, such as “parallel bar and ring acrobatics,” creating a “storm in the audience.” As he performed, Bishnu heard someone shout, “Did I not tell you, it is the same boy who has come back as a clown? He is the best performer.” Though it was his first performance, he won a silver medal that day. Bishnu later recalled: I was stupefied! Thank God I was in a clown’s dress or else everyone would have been witness to my highly emotional expressions that day. Lalbabu must have given such silver medals to many such students but it was like manna from heaven for me that day. I cried the whole night, tears of emotion. That silver medal gave me the incentive to proceed in this path for the last 40 years. This was not a one-time act; Bishnu “became famous as a clown” during the early 1920s. As he took up bayam, combat sports and feats of strength, Bishnu had two qualities that he felt propelled him to succeed: “determination finish a job” and a desire for praise. He candidly stated, “I paid full attention to anything I did so that I would be loved and praised.” Alongside Thakurta, Bishnu participated in boxing, wrestling and Jiu-Jitsu matches, lathi-khela (sticks), and lifting tonnage. They performed in Calcutta at Seller’s Circus and Gemini Circus, and at events in the villages throughout Bengal. The troupe organized demonstrations either for charity or to raise funds for the City College akhara managed by Thakurta. Read more about Bishnu Ghosh in Calcutta Yoga by Jerome Armstrong. In our normal bodily positions like standing or sitting, the head is above the heart. Pumping the blood from the heart up to the head requires fighting the effects of gravity, so blood pressure in the head is higher than other parts of the body.

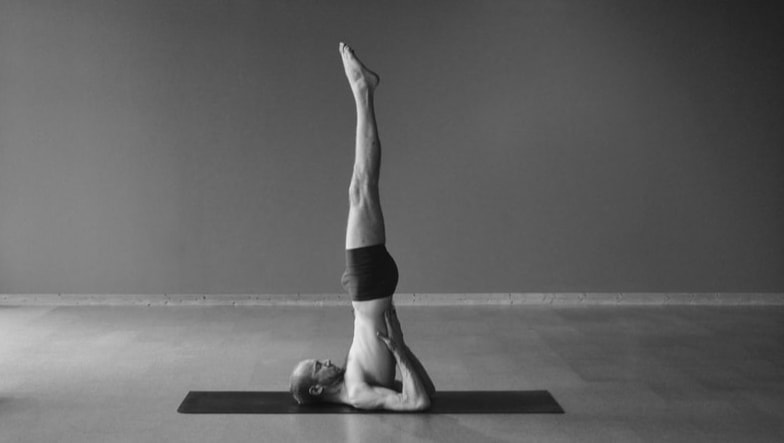

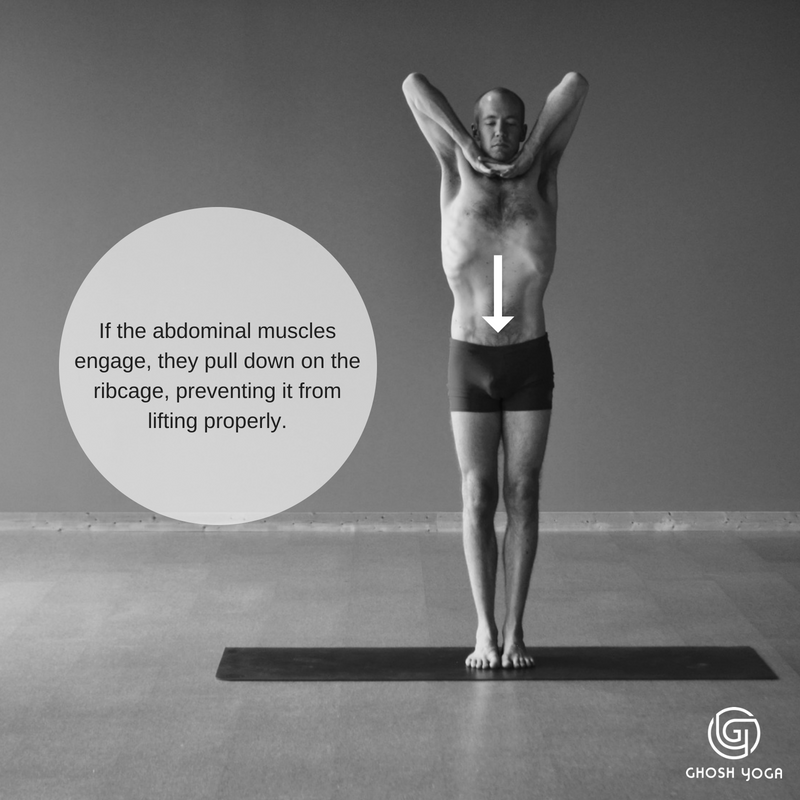

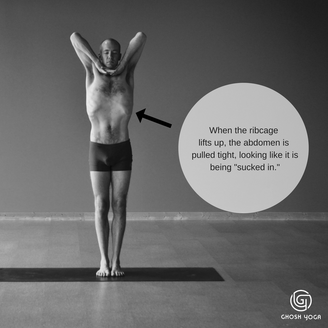

When we adjust the position of the body, as we often do in yoga practice, the head sometimes goes below the heart. When this happens, gravity pulls blood into the head, raising the blood pressure. Our body adjusts by decreasing the blood pressure in the head to protect the brain and face. This effect can be both positive and negative depending on our health and our bodies' ability to adjust the pressure. If we are healthy, the shifting of the blood pressure up and down can be beneficial, teaching our systems how to respond to changing conditions. This is why healthy people should put the head below the heart. If we have high blood pressure we must be very careful. Whenever the head goes below the heart, it is possible that the blood pressure will get dangerously high before the body responds. Or the body may not respond effectively and let the blood pressure stay too high for too long. So those of us with high blood pressure should take care when putting the head below the heart. We can do gentle "inversions" by bringing the head even with the heart or only slightly below. This can be done in forward folding positions and kneeling positions like Half Tortoise or Child's Pose. Una de las maneras principales en las que respiramos es con nuestro pecho. Los músculos entre las costillas causan que la caja torácica se expanda, llevando aire a los pulmones. Esto causa que los músculos abdominales se alarguen al ser jalados por la moción alta de las costillas. Los músculos abdominales deben de estar relajados para que las costillas se levanten por completo. Los músculos abdominales al ser jalados y la cavidad abdominal estirada hacia arriba, su circunferencia es reducida, esencialmente llevando el abdomen hacia adentro. Esta apariencia es engañosa, ya que por fuera parece ser como si los músculos abdominales se estuvieran contrayendo para “meter el vientre”. No es así.

|

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed