|

Cuando regresamos de nuestro primer entrenamiento, nuestros buenos amigos y mentores---David y Ken--- nos dieron un consejo importante: Cuando tomes una clase, toma la clase. Ellos explicaron que al progresar como maestro(a) de yoga, tu idea de lo que es correcto, bueno, efectivo, etc., crecerá. Será más y más difícil tomar clases sin ser crítico, o mas peor, arrogante.

Esto se volverá más difícil, porque claro, tenemos ideas de lo que una clase debe de ser. Aunque nos seamos un maestro(a), sabemos lo que nos gusta y no nos gusta. Mientras que nunca deberías sentirte inseguro en una clase, no es apropiado decir ninguna objeción a la clase verbalmente o con tus acciones. Si el maestro(a) te pregunta por tu opinión, es diferente. De otra manera tú eres el estudiante y el maestro(a) es el maestro(a). Al estar en la clase, aceptamos las responsabilidades del estudiante: aprender, escuchar y practicar. Al progresar como yogis, esto se vuelve más importante, no menos. Aprendemos que todos tenemos ideas que hemos construido, y parte de la práctica es notar y tratar de silenciar estas ideas. Durante una clase de yoga, no es nuestro trabajo educar al maestro(a) sobre los errores que han cometido. En ese momento, todo lo que haría es llevarnos bajo el camino incorrecto al faltarle al respeto al maestro(a) y hacer crecer nuestro propio ego. Claro, no es lo mismo que no tener opiniones. Más bien es simplemente una oportunidad para practicar la humildad. Todos tenemos opiniones, incluso opiniones fuertes que forman la fundación de la que enseñamos. Cuando escojamos tomar una clase, debemos tomar la clase.

0 Comments

We often get questions about namaste, a word that has become practically ubiquitous in western yoga classes, where most teachers will end class by saying it.

As you may already know, namaste involves placing the palms together in prayer in front of the chest. Often the head bows and the word namaste is spoken. The literal meaning is "I bow to you". It is a greeting and a display of respect. Namaste in Western yoga culture has been imbued with high meaning: that there is a divine being in me which recognizes a divine being in you. This belief comes from a spiritual philosophy called Advaita Vedanta, which argues that all the world is one; that any perceived separation between entities, including between you and me, is a misperception. This may seem like a lot of meaning to squeeze into one little word, and it is. In its most common sense, namaste simply means "hello" or "greetings". When deeper, more spiritual meaning is desired, you might be more specific by naming the entity to whom you bow: "Teacher, I bow to you", "God, I bow to you", "Highest self, I bow to you". THE HANDS It is easy to overlook the cultural reasons for the hand gesture. In the west, we shake hands or even hug when we greet. In India shaking hands is quite uncommon. It is impolite to touch other people, since the hands are used for other activities like eating and washing the body. The hands are of questionable cleanliness, so we keep them to ourselves when we greet one another. What happens instead is we touch our hands together in greeting, forming a prayer or namaste gesture. HOW & WHEN DID IT BECOME SO POPULAR The word namah is common in old Sanskrit texts. Like mentioned above, it is generally accompanied by something more specific, naming the entity to whom we are bowing with respect and devotion. What we often overlook is that namaste is a common modern Hindi word that has been used in recent decades by Indian yoga teachers and public figures who speak Hindi. There are many examples of Ghandi, Nehru and Osho stepping onstage before a large audience and assuming the namaste hand position. In the 1950s, 60s and 70s this captured the imagination of the Beat and Hippie generations in the West. They were quick to adopt the respectful and peaceful gesture. Over the ensuing decades, namaste has evolved from a respectful greeting to a full-on spiritual statement, which is perhaps overblowing it. OM We don't say namaste at the end of practice, nor do the Indian teachers we know or the Vedantic swamis with whom we have studied. When we're in India, we say it all the time as a greeting to people we meet. When we're in Kolkata, we say nomoshkar, which is the Bengali equivalent. There is, though, a word which carries significant meaning and history. It is what the swamis say at the beginning and end of every lecture, class, meditation and mantra: om. Om is a word that is present in the Vedas (there's even an entire Upanishad devoted to it) and the Yogasutras, explained as containing the sound and meaning of all creation. In our estimation, om is a more appropriate word to remind us of oneness, humility, respect and devotion. Palmstand is an unsung hero for the body, directly helping two of the most common physical ailments: a tight neck and a weak abdomen. These two problems lead to all kinds of issues in the body, nervous system and mind, making us uncomfortable, unhappy and perhaps even injured.

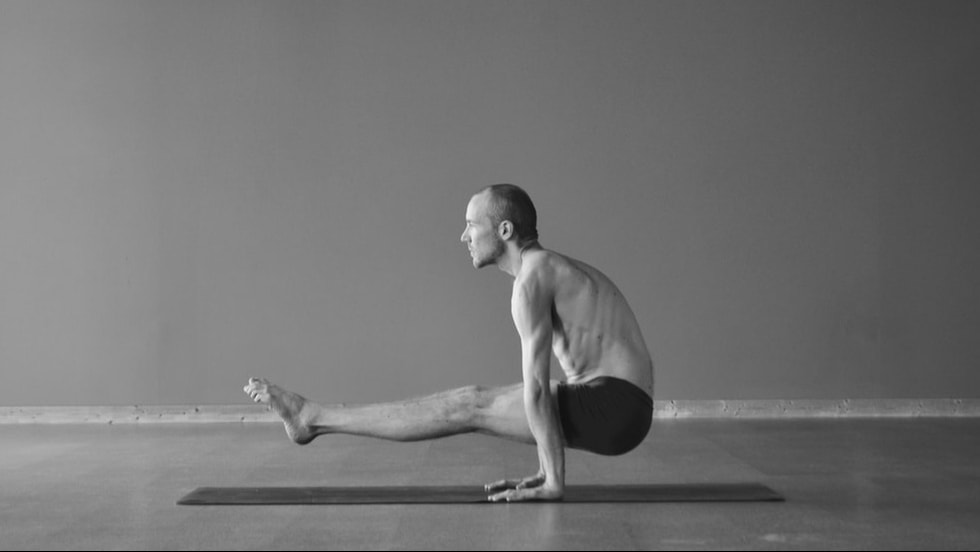

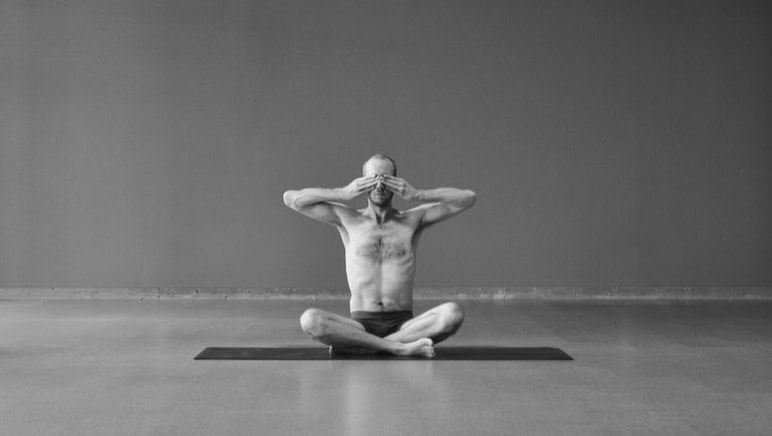

Palmstand is accomplished by sitting, placing the hands by the sides of the hips, and then lifting the butt and legs off the floor. It can seem impossible at first, but you can begin by lifting only the butt up and leaving the feet down. It can also help to put blocks under the hands, giving a little extra height. NECK & SHOULDERS In our culture we spend lots of time in front of computers, with our shoulders hunched up and forward. Over time this leads to a tight neck and tightness on the tops of the shoulders. This is exacerbated by the infrequency with which we push (or pull) things down with our shoulders. What ends up happening is the top of our shoulders and neck become overly engaged while the bottom of our shoulders, which act to counterbalance the top, are weak and underdeveloped. The way to remedy this problem is to develop strength underneath the shoulders by pushing them down strongly. This is where Palmstand comes in. The action of the posture requires a powerful downward push. When you do it, you may notice that your neck becomes long, as do the tops of your shoulders. If you do the posture regularly, you will develop strength under the shoulders, balancing the joint and releasing the neck and shoulder tops! ABDOMINAL STRENGTH It is well-known that most of us have weak abdominal muscles, and that this weakness can lead to all sorts of problems like poor digestion and back pain. This is why "core strength" has become so popular and exercise regimes like Pilates are making a comeback. In Palmstand the legs are held aloft by the abdominal muscles (along with the hip flexors), making them quite strong. If you find yourself struggling to lift the legs, know that your effort is strengthening your abs and that in time you will get them up. The posture ends up being quite engaged, with your muscles so tight that breathing is difficult. This is okay. Hold the posture strongly for a few seconds before relaxing and breathing. Then do it again. With practice, Palmstand balances the body and remedies two of the most common physical issues in our culture. The Ghosh Yoga Mentorship program officially begins today.

At the beginning of practice, when we know very little, it is enough to learn in a group setting like grade school or yoga class. In these situations information can be dispersed efficiently to a lot of people, so we can learn the basics and decide if we want to pursue a subject in depth. As we progress in our lives and yoga practice, it is increasingly important to get unique, individual instruction and feedback. It is said that the paths are many even when the goal is one. The more specialized we get, the less appropriate a classroom experience is since the lesson that is perfect for our neighbor might miss the point for us, and vice versa. The Ghosh Yoga Mentorship addresses the needs of yoga students and teachers who are ready for individual attention. You will have direct one-on-one communication with Scott and Ida via email and telephone, and they will help guide you on your path. - Ask the questions that come up, whether in your practice, teaching or study. - Get homework assignments, readings and tasks customized for your goals and needs. - Feedback and instruction on your postures or breathing. - Specific, individual meditation or mantra guidance. - Instruction and feedback on your teaching. - Advice about students, class structure, sequencing, etc. - Much, much more... It is impossible to predict your path and questions. What is important is having access to someone who can offer insight and support. Click here for more info about the Ghosh Yoga Mentorship program. The world outside calls the mind,

with voices, horns, billboards and email alerts, until the mind emerges and comes to reside in the world. The assault on the senses is like a day with no night. We become disoriented from stimulation, insane but unable to rest. Still, we think the key to relief is somewhere outside. Peace, rest and happiness do not lie in the world outside. They can not be found by sight, touch, hearing or taste. This is the first realization: that happiness lies within. Only with this can our journey toward actual peace begin. Start listening to the discussion around food; the words we use to describe it. You will hear little aside from comments about taste and satisfaction. "Yum" or "this is so good" or "tastes ok" or "definitely worth the calories."

What all of these have in common is their reference to taste, something that has become increasingly dominant in our idea of what makes good food. You may even hear healthy food---food that serves a useful propose to the function of our bodies---described with derision: "Ugh, this tastes healthy." Even though we occasionally pay lip service to the value of eating healthy, we drift farther and farther from the understanding that we eat to keep our bodies alive. Instead we eat to simulate our senses with aromas and flavors. We eat what smells good and what tastes good. We go to restaurants expecting a delicious experience. Even if we go to a health food store or eatery, the measure of value is most often in the taste. This relationship with food is bad for our minds. (It is almost inappropriate to call it food since that's not why we put it in our mouth. We should call it "flavor swallow" or something that signifies its true use.) Every time we stimulate the senses, the mind is drawn outward, causing it to seek satisfaction externally. But this ends up making us eternally unhappy, because the senses can never give satisfaction. They only bring more sensory craving. The way to happiness lies through resisting our sensory cravings until they become quiet. When our senses are quiet we can perceive things more clearly. With food this means that we must resist our cravings for tasty food, at least in their disguise as "good" food. Once we do this, our consumption of food becomes so much clearer. We understand eating as a process of nourishment, not of sensory simulation. We don't need to avoid all tasty things, we just need to recognize what they truly are. P.S. We do our best to not offend. Really, we do. And we know the sensitivity of this issue. If this article strikes a tender spot in you or brings up emotion or anger, take just one millisecond to recognize that, and that is enough for today. We are on your side! This morning we arose at 5 a.m. so we could be on the Ganges for the rising of the sun. As our guide constantly tells us, this is one of the holiest places in the world, and the Ganges river as it passes through Varanasi is lined with temple after temple.

The early morning is populated by people coming to the river and bathing at the ghats--- stone steps that lead down into the river. The water level of the Ganges varies drastically depending on the time of year, and it has just begun descending from its high point during the monsoon so the ghats are covered with dirt and clay from the receding current. The traditions here are old, and we pass by ghat after ghat of devotional bathers preparing for worship and the day. The funeral pyres at some ghats burn 24 hours a day, as bodies are placed atop 400 kg of wood and sprinkled with ghee (butter) and sandalwood to hasten their path to heaven. It is all juxtaposed with modernity, as everyone carries cell phones and our young boat driver has earbuds in, listening to the latest hits I assume. The tone of this city is much different than Kolkata. The modern ideas scrape against the grain of an ancient culture. Tourism is common in Varanasi, so the reactions to our white skin are distinct. Whereas in Kolkata we were curiosities and the locals simply wanted to take selfies with the strange white people, here in Varanasi we are marks, foreign tourists from whom to extract money. The concept of non-attachment is one of great importance in the study of yoga. Discussion of non-attachment, or vairagya (वैराग्य), appears in the YogaSutras 1.15-1.16. These verses talk about non-attachment as a type of consciousness in which we are not craving objects or being controlled by our senses. Non-attachment is not necessarily an action, but rather a state of being. We no longer use our likes and dislikes as the determining factor for our decisions.

When we are driven by our cravings, we exists in two states: giving in or resisting. These are very similar states of mind from a yogic perspective. In both cases we are using our thoughts to debate what action to take based on what we do or do not want to do. Maybe you can think of a time you really wanted something but resisted, or really didn't want to do something you had to do. Regardless of the action you chose, the inner debate is what is interesting from a yogic perspective. While non-attachment isn't technically renouncing our desires, that is the best way to begin the practice. When we notice a craving or desire, we first have to consciously abstain and break the pattern in our mind that creates the desire in the first place. Over time, it doesn't mean we never have the piece of cake (as the yogis would say!) but we aren't being controlled by our desire. In order to work on non-attachment we must practice it. Progress comes through being very aware of our emotional responses to all situations we find ourselves in. We must monitor our thoughts and our reactions by way of choosing not to associate with them. We must not attach to our thoughts. With practice we exist in a state of non-attachment while interacting with the world just as we always have. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed