|

Two weeks ago, the state of Alabama overturned a 30 year ban on yoga instruction in public schools. Now yoga can be taught in schools there, with a few caveats.

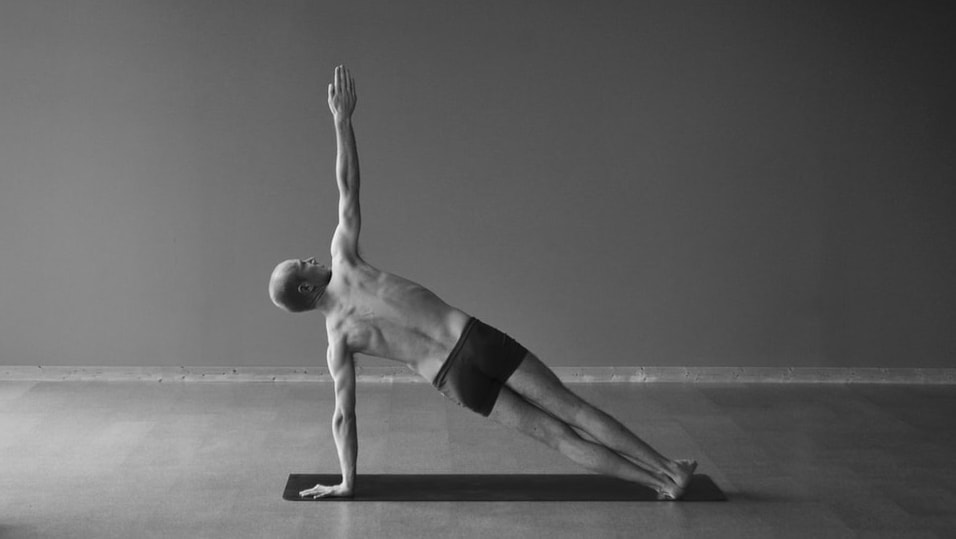

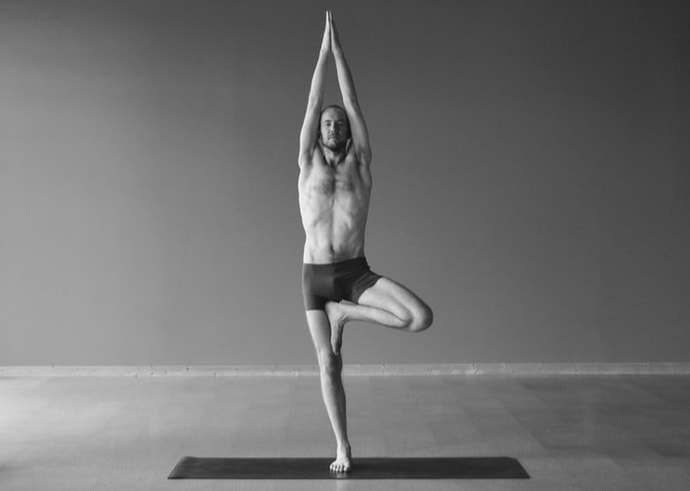

The bill continues the transformation of modern yoga into a secular, physical, health-centric exercise practice, a process that began about 100 years ago in India. As far as the bill promotes health in students, it is to be applauded. But its understanding of the essence of modern yoga is off the mark, which leads to a couple mistaken restrictions, like the exclusive use of the English language. According to the bill, "All instruction in yoga shall be limited exclusively to poses, exercises, and stretching techniques. All poses shall be limited exclusively to sitting, standing, reclining, twisting, and balancing. All poses, exercises, and stretching techniques shall have exclusively English descriptive names. Chanting, mantras, mudras, use of mandalas, induction of hypnotic states, guided imagery, and namaste greetings shall be expressly prohibited." These stipulations come from concerns over the possibility of yoga's inherent religiosity or spirituality. Religious teaching of any kind is not permitted in public schools, and some worry that even non-religious yoga practices are a trojan horse, smuggling Hinduism or Buddhism into the curriculum. At the root of the confusion is a common term: yoga. It can refer to old practices or new, spiritual, religious or physical. The confusion arises when we do not know which are being taught, or when we think they are all the same. The Alabama bill makes this mistake, equating yoga practice with Hinduism. It requires parental permission for any student to participate, including the statement, "I understand that yoga is part of the Hinduism religion.” Let’s look at this misunderstanding in a little more detail. Practices called yoga have been around for thousands of years. For most of history, yoga was spiritual, a practice of linking one's awareness with the eternal soul within, or with a deity. In this way, yoga can be associated with Hinduism. But yoga that is practiced today is different. In the early 20th century, yoga practice became largely physical and focused on health, downplaying or entirely dropping its spiritual and religious elements. According to yoga scholar Mark Singleton, conceptions of yoga in the 20th century are shaped by "modern physical culture, 'healthism', and Western esotericism." In other words, modern yoga is closer to gymnastics than prayer. Even though they share the same name — yoga — modern practice is fundamentally different from earlier spiritual forms. Confusion is common. Most people who do not practice yoga, and even many who do, mistakenly think that the postures and exercises in a yoga class are ancient and inherently spiritual in nature. But most of the stretches and asanas in a yoga class come from calisthenics, gymnastics and dance as recently as the last few decades. As such, they are exercises that look good, feel good and improve our health. Singleton writes, "among outsiders and practitioners alike, there is often little awareness that these modes of [modern] practice have no precedent (prior to the early twentieth century, that is) in Indian yoga traditions.” So it is no surprise that parents and politicians fear inherent Hinduism in yoga, even though little or none exists in its modern iterations. THE SANSKRIT LANGUAGE This same misunderstanding appears in the Alabama bill with regard to language. Though it is not stated explicitly, the insistence on "exclusively English descriptive names" seems to be a way to prevent the use of the Sanskrit language, most likely due to fear that Sanskrit will smuggle in Hinduism or Buddhism. But non-English languages are fundamental parts of many disciplines. In music, every student learns the Italian allegro, andante, forte and piano, words meaning fast, slow, loud and soft. And biologists often use Latin to classify species like homo sapiens. Some yoga postures are named after Hindu deities. For example, Hanumanasana is named after the god Hanuman; Virabhadrasana is named after Virabhadra; Vasishthasana is named for Vasishtha. These names and their deities are rightfully forbidden from public schools, just as any mention of Moses, Jesus or Mohammed would be. But other postures are named for secular objects like shapes and animals. There is Trikonasana, the Triangle Posture; Vrikshasana, the Tree Posture; Bhujangasana, the Cobra Posture, among countless others. Surely these names do not infringe upon religious freedom or inherently imply Hindu worship, whether in English or Sanskrit. And there is no harm in learning the Sanskrit word for tree. At its core, then, the new bill in Alabama continues the secularization, exercise and health focus of modern yoga. In this way, it isn't terribly different from the twentieth-century innovations of Vivekananda or Yogendra, who removed unattractive traditional beliefs in favor of modern ones. — Singleton, Mark. 2010. Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford University Press.

1 Comment

The issue of cultural appropriation has been troubling yoga lately. Did the West steal yoga from India? Does India own yoga? Do Indians naturally and inherently understand yoga because of their cultural heritage? Is it in their blood? Some have suggested that non-Indians should not teach yoga.

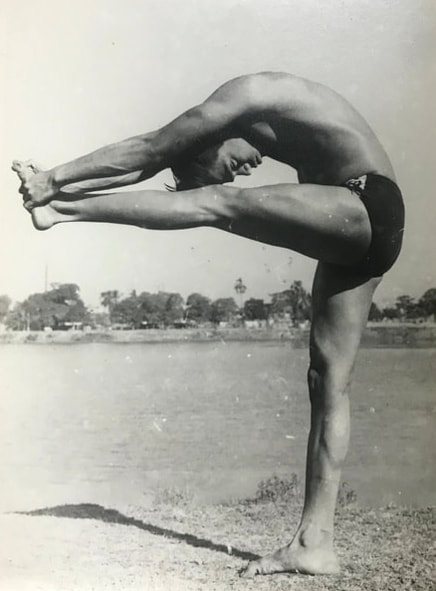

Three elements are worth stating briefly before we answer the central question. First, any claim that intelligence, knowledge, understanding or ability can be judged by a person’s heritage or race should be recognized for what it is. At best it is nationalism, at worst it is racism. With yoga, the sentiment is understandable on several levels. Yoga has become a billion dollar industry beyond India's borders. Furthermore, much about what modern yoga is today shifted drastically while India was under British rule. The desire to reclaim a popular system as one’s own is relatable. Yoga, like many other trades, practices or professions can be passed down generation to generation. At a young age, the next in line takes over the family business. They grow up around it and learn everything there is to know about it from the older generation. This is different. This is closer to a master/apprentice or guru/disciple relationship. In this case, the second generation will have knowledge and understanding that the outside world won't have. But this is because of the immense time spent learning and studying the craft. If the child of an expert chooses not to study or practice yoga for example, they cannot expect to know a great deal about it even if they are directly related to an expert. Second, heritage of a subject or art form in a country does not give that country exclusive ownership of it. Ideas and goods have been traded internationally for thousands of years, evolving as they go. The Chinese cannot claim the exclusive right to make paper, the Babylonians mathematics, nor the Indians yoga. Third, we need to be clear about what we mean by 'yoga'. This may seem obvious, but it is nuanced enough to deserve a little explanation. There is no doubt that yoga originates in India. The ancient Katha Upanishad is its first known explanation. For thousands of years, yoga was a spiritual practice of uniting one’s awareness with an eternal spirit within, or with a deity. In the twelfth century, a practice with bodily elements developed, called hathayoga, the 'yoga of force'. But the goal was the same, to create spiritual unity with a higher being. In the early twentieth century, this changed drastically. Over the course of a couple decades, yoga was refashioned as a modern, scientific, physical practice for health. Modern yoga represents a fundamental break from the older spiritual iterations. It shows influence from European physical cultures like gymnastics and calisthenics. As such, even India’s claim as the singular authentic source of modern physical yoga is worthy of healthy debate. But let’s get back to the central question: who should be teaching yoga? The answer is the same as for any topic, whether mathematics, physics, astronomy, music or literature. A topic should be taught by those who have knowledge of it. Regardless of their age, gender or race, a teacher needs no more — and no less — than expertise of their subject. This gets more complicated because of the unequal power structures permeating the world. Those that know should teach. However, those that have resources should work to make sure that those who have less still have the opportunity to learn if they choose to. Perhaps the question is not who should teach, but rather how do we make high quality education affordable and available. This issue has quickly moved in the wrong direction as more and more "teacher" trainings see big money to be made. This is in exchange for the promise of the title of teacher, often with not enough regard for the task of actually training a teacher. As for the suggestion that non-Indians should not teach yoga, the nationalistic element should quickly be discarded. Furthermore, we need to address the quality of yoga teachers. The only worthwhile question to ask about a potential yoga teacher is this: do they know what they are doing? Today we mourn the passing of yet another important figure in the Ghosh yoga family. Montosh Choudhury was a lifelong yogi, a performer, a teacher, a husband and a father. He will be missed tremendously. I had the chance to spend some time with him over the past few years. I will share some stories along with some details about his life. In 1944, Choudhury was born in Burma (present day Myanmar). As a young man, he sent a letter to Bishnu Ghosh. He requested that Ghosh teach him and Ghosh agreed. Choudhury then went to India and began his training. He trained in stunt work like bending iron rods and mastered difficult yoga asanas. As a young performer, Choudhury won bodybuilding awards and was recognized for his physical abilities. He was part of Bishnu Ghosh's performance troupe that went to Japan in 1968. There he was recognized by Fuji Telecasting as a very popular performer.  Montosh Choudhury & Ida (April 2019) Montosh Choudhury & Ida (April 2019) History in the form of photos and documents is easily lost in Kolkata. The heavy rains and humidity make preservation difficult. It is rare that someone is a good record keeper who has held onto photos. Luckily, Choudhury was this rare exception. He had scrapbooks and boxes of well kept photos. Furthermore, he was a generous, patient and kind person and eagerly shared his treasures. He shared photos of his stunts and asanas like the one pictured above. In 1986, Choudhury founded the Swasthyasri Yoga & Physical Culture Center. Until very recently, he was still writing yoga prescriptions and running the center. As I sat with him, our discussion would occasionally be interrupted by yoga patients coming to see him. I would immediately get up to leave to give him privacy. He would say, "No, no, just a minute." One one occasion, a woman carrying a young toddler walked in. I sat, eating the sweets he had given me, while he examined the toddler's legs. They were slightly bow-legged and the mother was concerned. He wrote a list of exercises for the child to do and tore the list off of his prescription pad. Choudhury's assistant then took the mother, child and list of yoga exercises and away they went. He was knowledgeable and confident. He had likely written thousands of prescriptions by that point.  From left to right: Mukul Dutta, Montosh Choudhury, Jerome Armstrong (April 2019) From left to right: Mukul Dutta, Montosh Choudhury, Jerome Armstrong (April 2019) Though he was nearly 80 years old, he was still quite strong. On one meeting, he requested that we "test his abdominal strength." I was visiting with Jerome Armstrong, author of Calcutta Yoga, and Mukul Dutta. Choudhury asked Jerome to press on his abdomen. As he did, the roller chair Choudhury was sitting in slid back. Mukul Dutta came and held the chair in place. They were all laughing and enjoying the playful and boyish moment. Dutta and Choudhury had not seen each other in many years. It was a lovely reunion. Like many from his era, Choudhury worked tirelessly throughout his life. He promoted yoga in West Bengal through competitions, seminars and shows. He did not show any sign of slowing down or that he felt his work was done. After one meeting, he asked that we shake hands for a picture. He wanted to stay in contact so that he could visit America and continue spreading his knowledge of yoga. Both yogic and Buddhist traditions emphasize the inherent suffering of being alive and being human. And both traditions place great importance on removing suffering in order to live contently and peacefully. But these traditions, focused as they are on our conceptions of the self and the world around us, tend to zero in on one kind of suffering in particular — suffering which comes from desire and attachment.

There are other forms of suffering, too. And it is vital to understand what we are talking about when we discuss 'removing suffering'. As we see it, there are three distinct forms of suffering. 1. EXISTENTIAL DISTRESSS It may be obvious to state that we are here as living, breathing beings. We are born, we live for awhile, and then we die. This period of 'being' is defined by a physical, biological form, a body which is shot through with nerve endings and loaded with self-preserving instincts. These characteristics are shared by every living being — whether human, animal, insect or amoeba. They are inherent in the physical nature of our being. When the existence of our physical being is threatened, we experience distress. This happens when we are hungry or starving, when we have no shelter, if we are threatened with physical violence, etc. These create real, visceral suffering that is common to all living beings. You can think of it like this: If another animal would suffer in this situation, due to a threat to its life, it is this type of existential suffering. 2. PAIN Another result of having physical bodies is that they are sensitive. If I hit my finger with a hammer, or cut my face, I will experience pain no matter how enlightened I am. Neurological scans show that the brain registers physical pain acutely, even in meditating monks. There is no way around this as long as we inhabit these bodies. 3. THE SUFFERING OF EGO, DESIRE AND ATTACHMENT The third kind of suffering is uniquely human. It is the target of the systems of yoga and Buddhism. While we can not remove the first two kinds of suffering while we are alive, this third type can be eliminated to a large degree. As humans, we have an acute sense of who we are and how we are different from those around us. This sense of individual identity is called ego by the yogis. Modern western culture cultivates this sense of identity, encouraging us to embrace our individuality and live out our desires — who we wish ourselves to be. As powerful as this idea may be, it is still only an idea. We build much of our lives around this idea of self, and it causes us great suffering. Our desires and attachments stem from our ego, and they cause us to hold onto things that are fleeting by their very nature. A job, a car, a cookie, a spouse, our own identity... all these things change over time and eventually disappear altogether. When we link our happiness to them, we are setting ourselves up for suffering because they are transitory. To paraphrase the Yoga Sutras, we are taking impermanent things and imagining them to be permanent. It is a recipe for trouble. REMOVING SUFFERING The traditions of yoga and Buddhism insist that the third kind of suffering can be halted by stopping it before it starts. Like weeding a garden, we remove our desires, attachments and ego so that contentment may grow and thrive. The first two kinds of suffering — existential distress and pain — are unavoidable elements of living in these bodies. When we talk about 'removing suffering', this does not mean that we will never be hungry, never fear for our lives or experience pain. It means that we will see ourselves and the world more clearly, thus ceasing to mistake our own ideas of self for reality. A short while ago, we decided to accept donations for Covid relief in India. We were not sure what to expect, but so many of you donated so generously! We committed to matching up to $1,000. You sent much more than that. The current total is $3,803!

A portion of the funds is going to the Patharpratima Runners, who are working in a very rural part of Bengal. Recently, they organized a blood donation site because blood banks are running out of supplies. They didn't know if anyone would show up, but they met their goals quickly and easily through the generous spirit of those who showed up. As Covid ravages India, other medical issues do not go away. This is one way of trying to prevent other disasters from piling on top of Covid-19. They are also organizing the distribution of 500 face shields, 1000 masks, 500 bottles of hand sanitizer and 500 bottles of soap to the water taxi drivers. These drivers transport people between 15 small islands and the mainland. You may have heard that much of the Covid relief in India is a grassroots effort. It is being done by people on the ground there. They are communicating where hospital beds are available, organizing free meal delivery services to those who have tested positive or are sick, and helping out where they can. With your donations we will continue to support these efforts for as long as we can. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed