|

It is hard to be a student. We are faced with juggling what we already know along with new information. As our bodies change, our minds change, and our practices change, we have to constantly adjust. Here are some tips for being a good student.

1. Do the work No matter how good the teacher is, they cannot do the work for us. We need to practice in order for learning to be a good use of our time. This means putting in effort every day. 2. Be prepared Ask the teacher questions that have come through practice. This is the difference between "How do I do the posture?" and "While practicing I realized I don't know how to bend my spine effectively. Can you watch and see what you think?" The first question shows no initiative to try and figure it out or a commitment to our own practice. The second question is what a teacher is there for: to guide us through roadblocks. 3. Listen When assuming the role of a student, we are agreeing to learn from the teacher. While questions may arise for us, the best thing to do is listen. Give it a chance. If we immediately question what the teacher says, we are inhibiting our own chance of learning something new. 4. Be patient Every time we learn something new we are a beginner again. This is tough to swallow. It's like a constant cycle of big fish/small pond to small fish/big pond. It's important to remember that we're not bad at the practice, we are simply progressing. When something is new, we won't be good at it. That is exactly what practice is for. We have to embrace what we are not good at, put in the work and be patient. Trust practice. It always works.

1 Comment

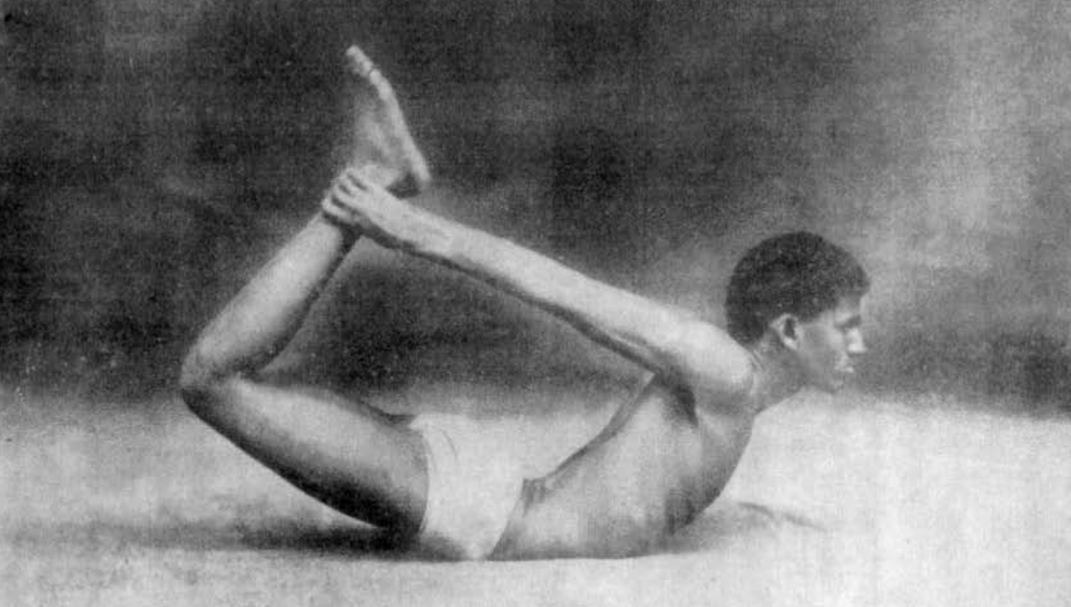

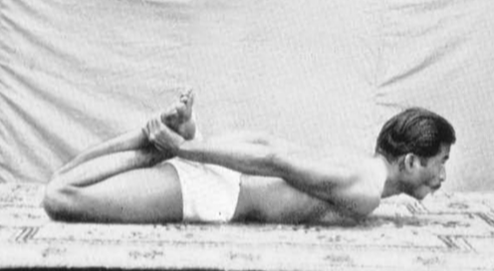

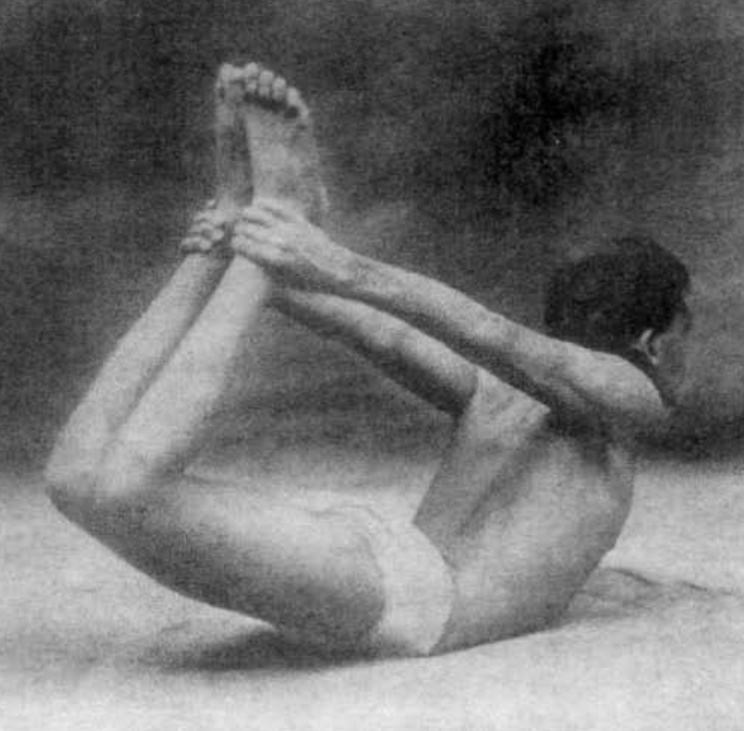

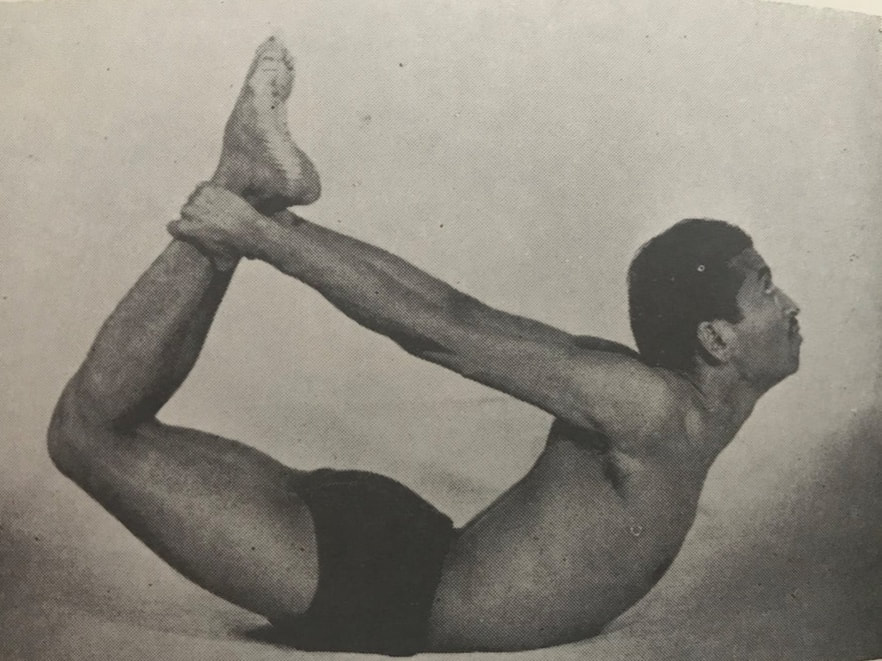

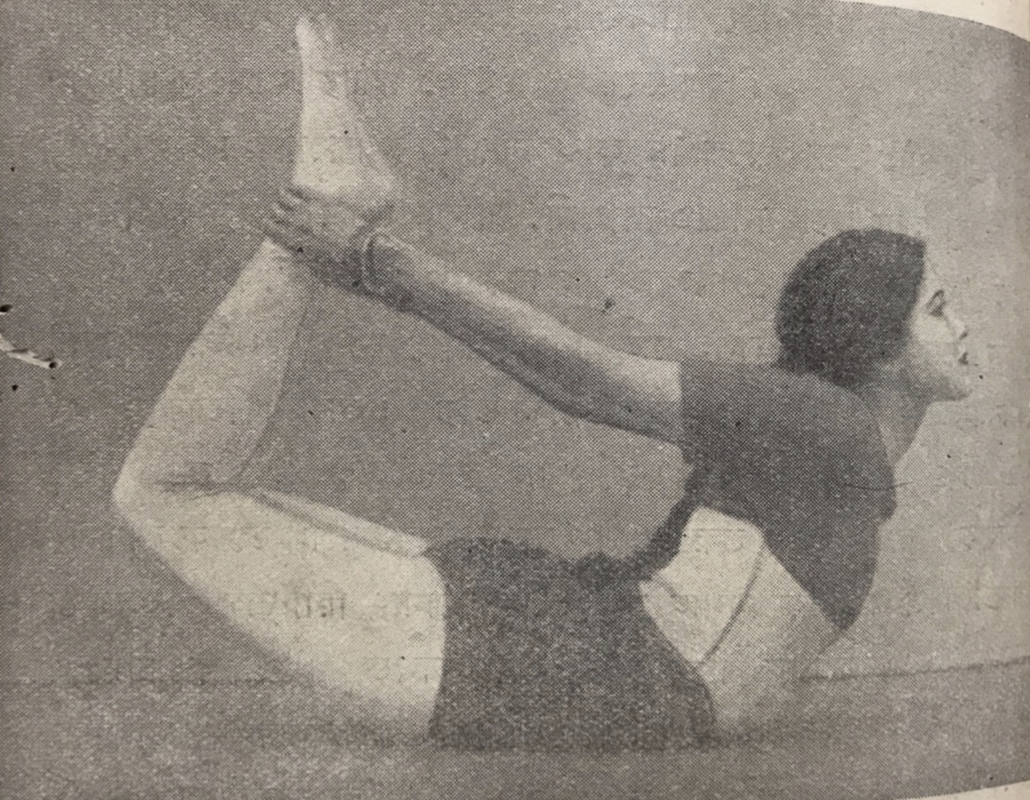

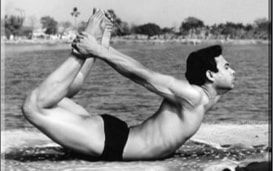

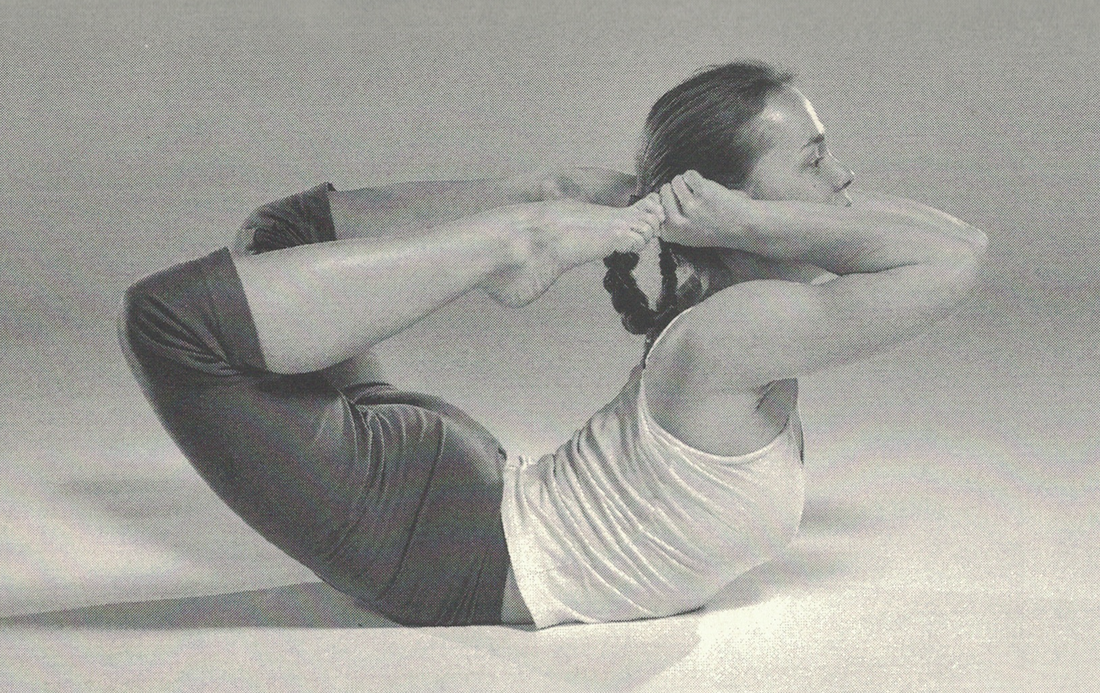

Read about the premodern version of Bow Posture, dhanurasana, here. For the past 100 years or so, Bow Posture is done lying on the belly, holding the feet or ankles, and bending the body backward, as pictured above in 1925. Prior to that, the posture seems to have been done sitting and pulling the feet toward the ears. The question remains: Where and when did the posture transition into its modern iteration?

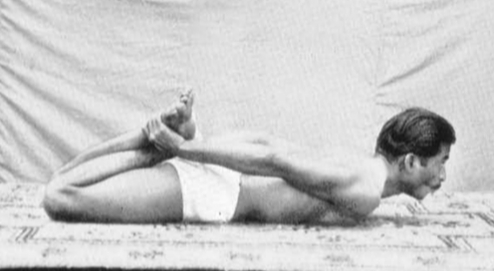

These premodern prone backbends are not called Bow Posture. By 1925 when Yoga Mimamsa publishes instruction, the modern die for dhanurasana seems to be set.

Kuvalayananda's book Popular Yoga Asanas from 1931 also includes Bow Posture, which is no surprise since it is drawn largely from issues of Yoga Mimamsa. Krishnamacharya's Yoga Makaranda in 1934 is curiously devoid of the posture. It makes one wonder about the influence of the Sritattvanidhi above.

Nearly every modern text that we examined contains the posture, from North India's Shivananda lineage, East India's Ghosh lineage, South India's Krishnamacharya lineages, to Europe.

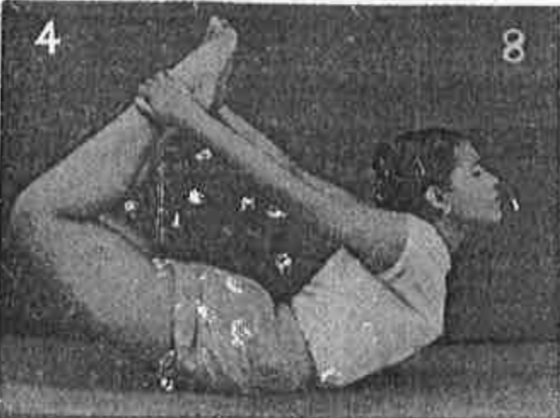

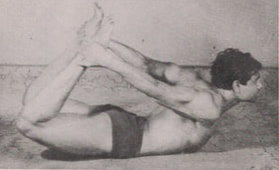

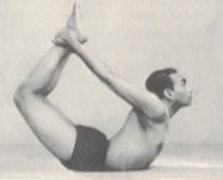

All the students of Bishnu Charan Ghosh include Bow Posture in their instructions. This includes Buddha Bose (above), Labanya Palit in 1955, Ghosh himself in 1961 (demonstrated by his daughter Karuna), Dr Gouri Mukerji in 1963, Monotosh Roy in the 60-70s, and Bikram Choudhury in the late 60s.

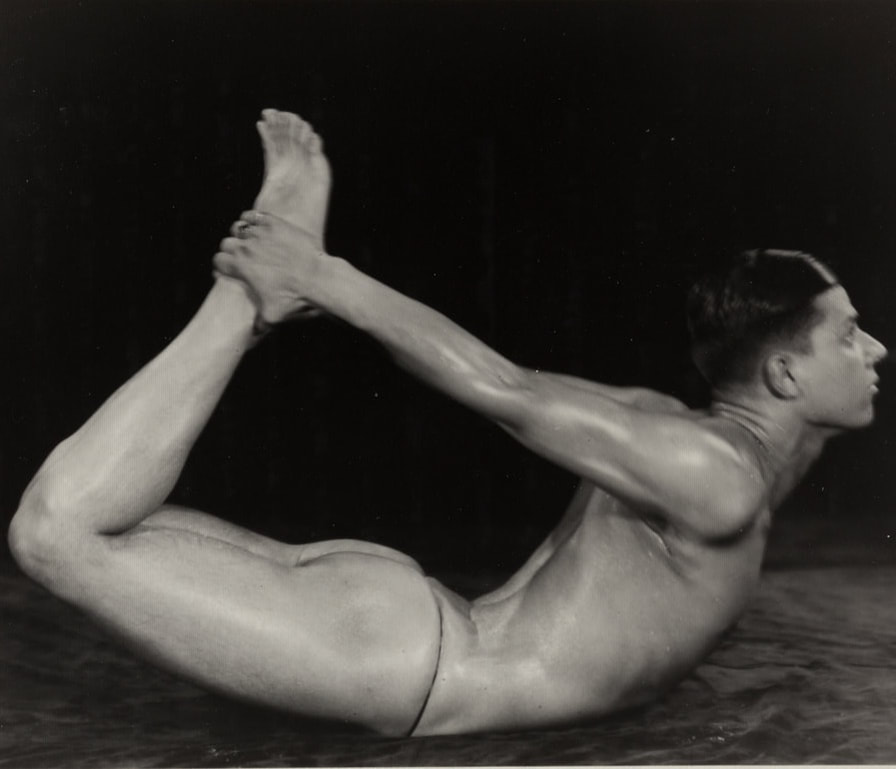

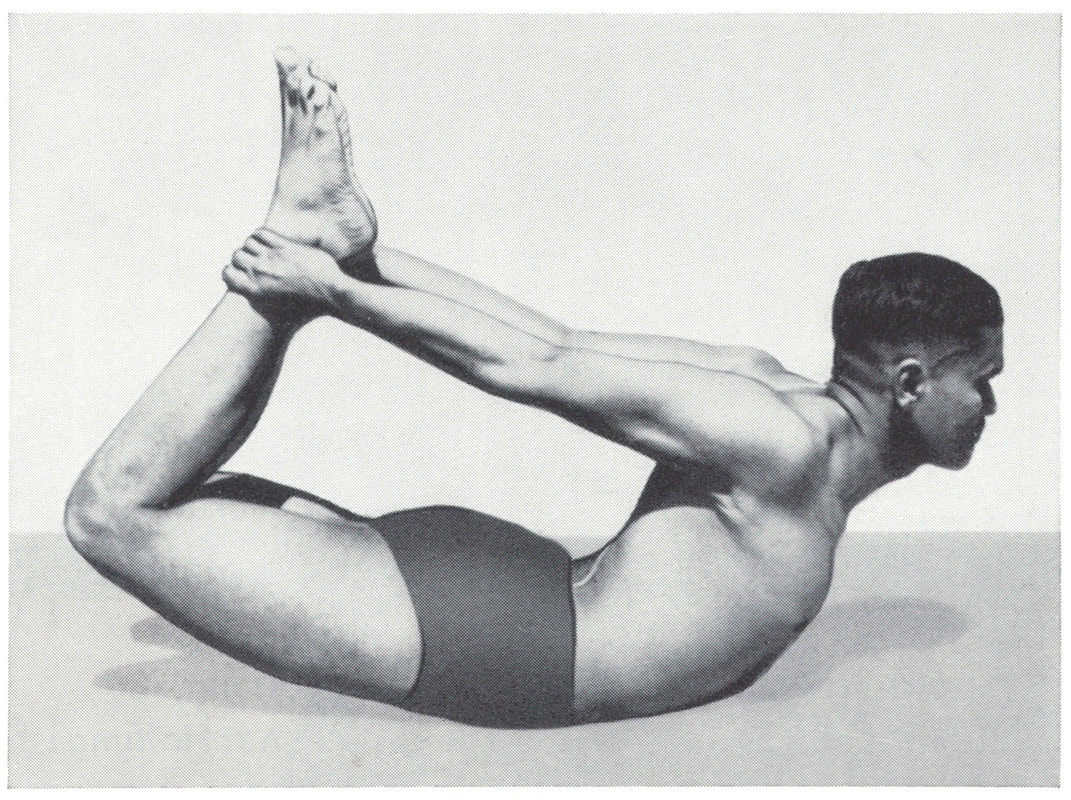

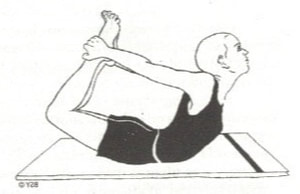

Iyengar, in his hugely influential Light On Yoga, is specific about where to carry the body's weight and also to keep the knees slightly apart: "Do not rest either the ribs or the pelvic bones on the floor. Only the abdomen bears the weight of the body on the floor. While raising the legs do not join them at the knees, for then the legs will not be lifted high enough." (Iyengar 1966: 101-2)

The instruction and performance of Bow Posture has been mostly consistent from about the 1920s. It is still unclear when it transitioned from the premodern, seated version into the prone backbend. Its hyper-modern shift to greater depth that resembles contortion more than dhanurasana is also interesting, but a topic for another time.

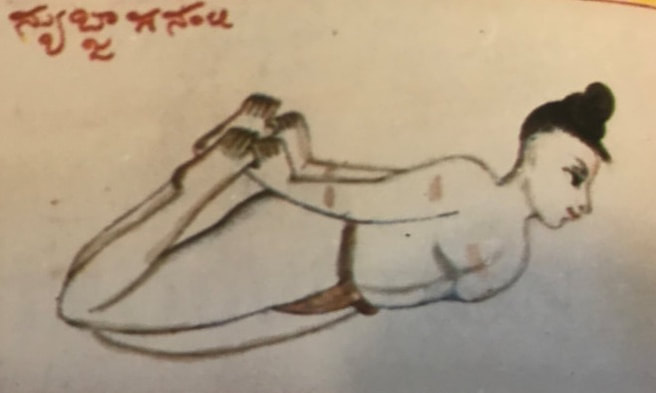

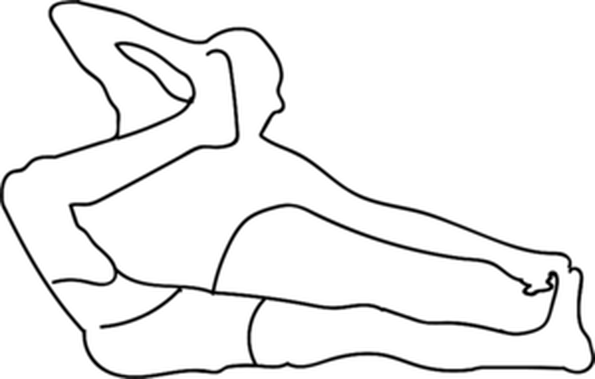

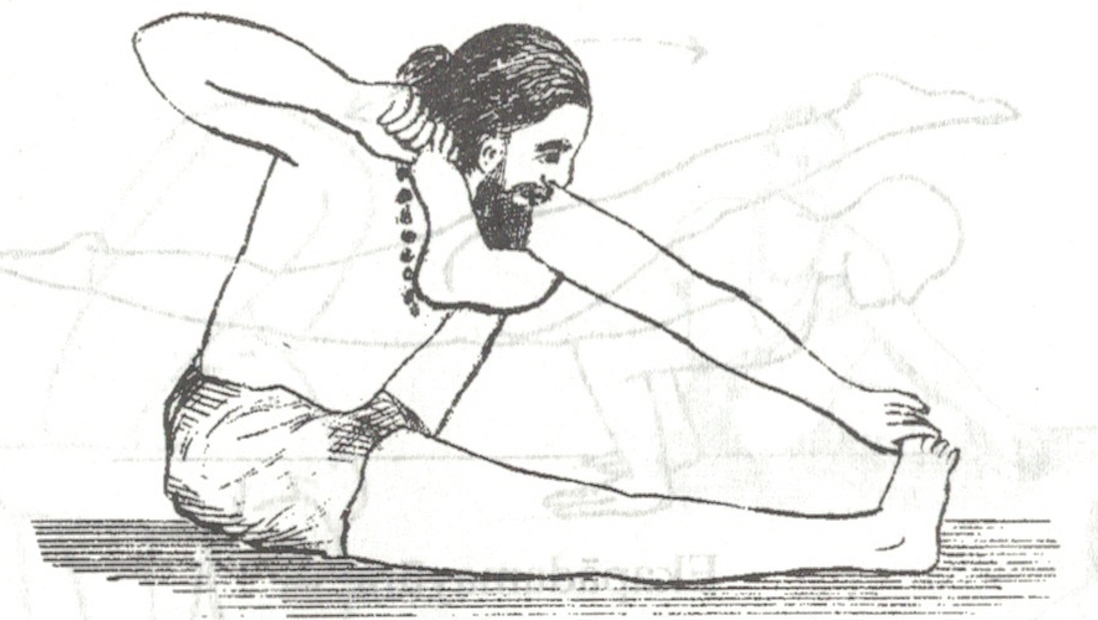

Bow Posture, dhanurasana, is one of the few postures of premodern Hathayoga that is not a seated, cross-legged, meditative position. Its first known instruction is from the 15th century in the Hathapradipika, and it is also included in the 17th century Hatharatnavali and the 18th century Gheranda Samhita. Interestingly, these premodern versions of Bow Posture may be different from the modern understanding. The modern version of Bow Posture, which has been prominent for the past 100 years or so, is done lying on the belly, holding the feet or ankles, and bending the body backward. Prior to that, the posture seems to have been done sitting and pulling the feet toward the ears. Bow Posture's earliest known instruction is in the 15th century Hathapradipika: "Bring the toes as far as the ears with both hands as if drawing a bow. This is Dhanurasana" (HP 1.25). (1) The Hatharatnavali from the 17th century repeats the Sanskrit instructions word for word. Here is a different English translation: "The big toes are held with the hands and are pulled up to the ears (alternately). Thus, one assumes the shape of a stretched bow. This is dhanurasana" (HR 3.51). (2) This posture is done sitting and pulling one foot to the ear as the other leg stays straight, making the body look like a drawn bow. There are two ways that the instruction has been interpreted, depending on whether the hand grabs the foot on the same side of the body or opposite. So this posture has been interpreted as pictured at the top, with the hand pulling the same side foot toward the ear; or with the leg crossing the body as pictured directly above. The instruction is not specific, making it likely that crossing the body is not intended. Nowadays, these positions are still taught sometimes. They are often called akarna dhanurasana, which means Bow to the Ear Posture; or akarshana dhanurasana, which means Bow Pulling Posture.

Bow Posture is also in another well-known premodern text, the Gheranda Samhita, from the 18th century. The instruction has changed a little from the Hathapradipika and Hatharatnavali: "Stretch the legs out on the ground like a stick, extend the arms, hold both feet from behind with the hands, and make the body curved like a bow. That is called Dhanurasana" (GS 2.18). (3) The interesting new instruction here is that the feet are held "from behind". Some interpret this as bending the legs backward and holding the feet, as one does in the modern backbend. But it is entirely possible that this is the same posture as instructed earlier, and the cue to hold the feet from behind is not particularly ground-breaking. The first words in this instruction, to "stretch the legs out on the ground like a stick", are identical to the instructions for Stretching Posture, paschimottanasana. This is perhaps a clue that the Bow Posture in the Gheranda Samhita is intended to be done sitting down with the legs stretched forward.

It seems most likely that the premodern Bow Posture was intended to be seated, pulling the toes toward the ears. The questions arise: When and why did it shift to the modern understanding of a prone backbend? As we will explore next, it seems to be established as the 'modern' Bow Posture by the 1920s.

(1) Akers, Brian Dana, trans., 2002 Hatha Yoga Pradipika NY: YogaVidya.com (2) Gharote, M.L., Devnath and Jha, editors, 2014 Hatharatnavali Lonavla Yoga Institute: Pune [2002] (3) Mallinson, James, trans., 2004 Gheranda Samhita NY: YogaVidya.com As we write this, from our home base in Minnesota, we have been reflecting on issues of race in yoga. From a philosophical perspective, any perceived difference between people (or beings of any kind) is not only a problem, but the cause of suffering.

In Samkhya, all physical matter is pakriti and therefore, not purusha. Meaning, bodies, skin, physical features are all of the material world. While the material world is real, we suffer because we mistake it for who we are. Liberation is the knowledge that we are not matter, but spirit. In Advaita Vedanta, names and forms are nothing but Brahman. It is Maya, or illusion, that makes us see individuals as separate and prevents us from seeing everything as one. This sense of separation is why we suffer. Here, liberation is knowledge of the true self. This self is the same in all beings. We were recently in a class where we were studying the Upanisads. A classmate raised some issues with a passage that we thought seemed standard at first glance. The passage says this: Lightness, health, the absence of greed, a bright complexion, a pleasant voice, a sweet smell and very little faeces and urine-- that, they say, is the first working of yogic practice. Svetasvatara Upanisad 2.13 Our classmate highlighted "lightness" and "a bright complexion". When he pressed on, it was revealed that it could literally mean a light color of skin. Let's hope that was not the intended meaning for the verse. Regardless, it is a reminder to keep our eyes and ears open. So, this is a time to carry on as people and as yogis. As students we have to be aware of what we don't already see. To continuously learn, question and practice with as much humility and discipline as we can muster. As yogis we need to be ever kind, peaceful and clear with our words and actions. Black lives matter. Racism is wrong. On down the path we go. There is a whole lot of stress and anxiety in the world right now. As yoga teachers, we can offer our students tools that can help. Here are a few ideas to consider.

Forward Bends of the Spine Forward bends of the spine help to activate the parasympathetic nervous system. Because of the compression of the front side of the body, they can help to calm the body and lower the heart rate. Postures such as Rabbit Pose, Stretching (with a rounded spine) or Half Tortoise fall into this category. Teach your students to focus on their exhales. The lungs are compressed in these positions and therefore the breath will be small. Be careful not to confuse this with forward bends of the hips such as Paschimottanasana with a straight spine. Also, be aware that backbends, while fabulous for many reasons, do the opposite of forward bends. They activate the sympathetic nervous system and raise the heart rate. In moments of stress or anxiety, be conscious of this if you're teaching in a high stress situation. Postures with Abdominal Breathing Breathing with the diaphragm is calming. Since this is not possible in many postures due to the muscular engagement necessary for the posture itself, emphasize postures that allow for this type of breathing. These postures include Shavasana, Wind Removing and Half Tortoise. Language like "breathe into your belly" or "feel your belly rise on the inhale" is helpful. If you see students with their chest or shoulders moving, remind the class that only the abdomen moves in this type of breathing. Pranayama There are two breathing exercises that are very simple and very effective for reducing stress. These are Chandraved Breathing and Even Count. For Chandraved Breathing, the inhale is always through the left nostril only and the exhale is through the right nostril. Don't make the breath too slow, just 4-6 counts for the inhales and exhales. (See below for further instructions) Even Count breathing is a practice of making the inhale and exhales even and smooth. Use an short count such as 4 counts in and 4 counts out. Anything beyond 8 counts in and out is not necessary for the purpose of reducing stress. Keep the count short, but even and consistent. Also, remind your students that there should be no stress or tension in their breathing. If it's too difficult, they can just breathe normally. Teach to the Class In Front of You Don't be afraid to add these practices into your teaching or adjust your classes to fit the needs of your students. As always, we're here to help. Leave a comment or email us if you need further instruction or information on these practices. Chandraved Breathing instructions: "Bring your right hand in front of your face. Close your right nostril with your thumb. Inhale through the left side. Close the left nostril, open the right and exhale. Close the right, open the left and inhale...." Repeat. |

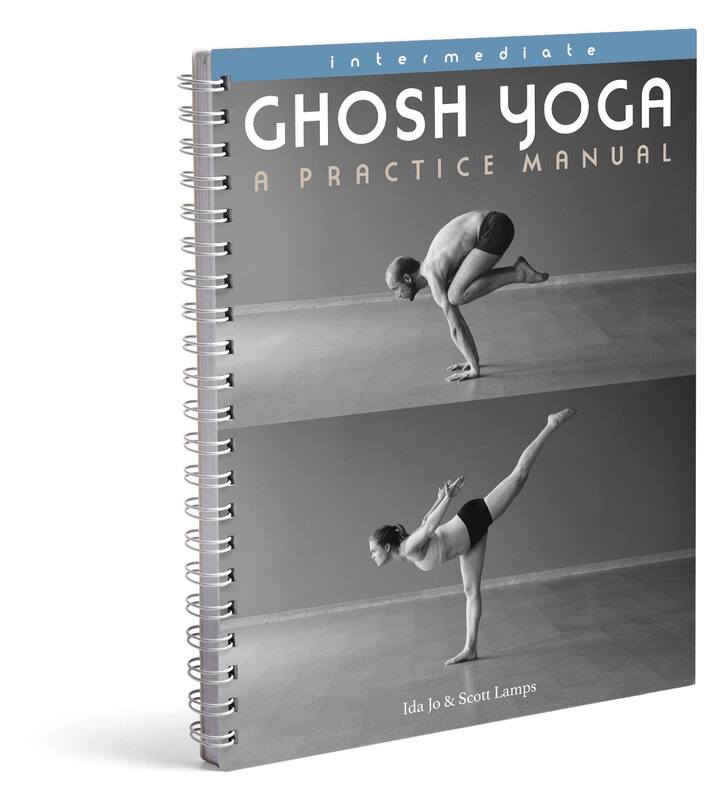

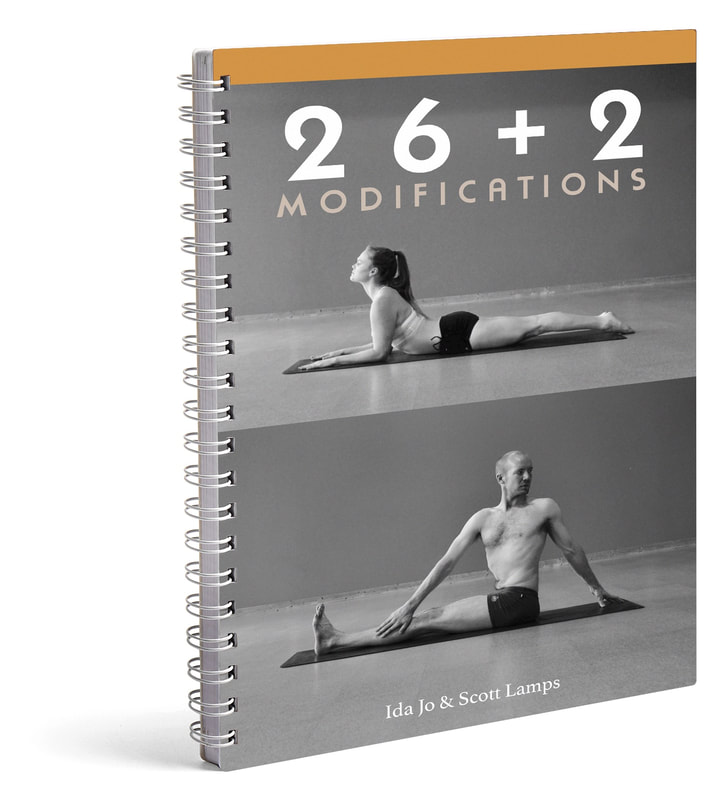

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed