|

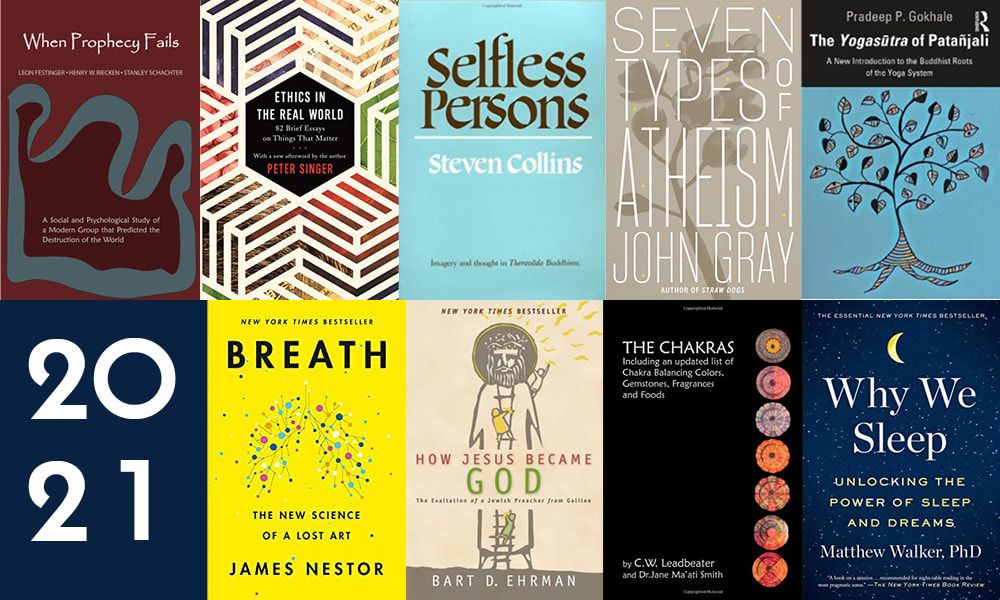

Gosh I love to read! Every book is an opportunity to see the world from a new perspective, to learn something from an expert, or to peer through a window to a different time and place. Here is a short list of books I read this year that had a profound impact on me. They are not new books. In fact, some of them are quite old. But they are all valid, and they meant a lot to me this year. WHEN PROPHECY FAILS by Festinger, Riecken and Schachter This work of social psychology from the 1950s dives into the mentality, actions and beliefs of a UFO cult. But it is so much more than that: an exploration of how our minds react when we may be wrong about something we really believe in. The authors build the case that, even when we are confronted with evidence that we are wrong, we essentially double-down in our beliefs. It is a chilling conclusion — that humans are sometimes immune to changing our minds. As the authors write, "when people are committed to a belief and a course of action, clear disconfirming evidence may simply result in deepened conviction". After reading this book, it is hard not to see this phenomenon all around us in the world today. ETHICS IN THE REAL WORLD by Peter Singer Ethics and morality have become especially important to me this year. Perhaps it is due to the ongoing pandemic and the acute awareness of how my actions can impact others. I stumbled upon this book, which contains 82 short essays about various ethical conundrums — from geopolitics to religious freedom, eating meat to climate change — and thought it would be a good overarching introduction. It is. Singer writes with remarkable clarity about ethical issues of all sorts. And the brevity of the essays means that nothing is belabored. SELFLESS PERSONS by Steven Collins This scholarly dive into the Buddhist concept of non-self is deep, complex and absolutely stunning. The idea that there is no eternal Self can be confounding and frustrating, especially when compared to other systems that insist upon its existence. The importance of non-self is summarized best in Collins's introduction: "this belief in a permanent and a divine soul is the most dangerous and pernicious of all errors, the most deceitful of illusions, that it will inevitably mislead its victim into the deepest pit of sorrow and suffering". SEVEN TYPES OF ATHEISM by John Gray I'm a sucker for an analysis of human spirituality in all its subtlety, diversity and contradiction. Gray's book does not disappoint. He begins by defining an atheist: "anyone with no use for the idea of a divine mind that has fashioned the world...It is simply the absence of the idea of a creator-god". This leaves a lot of room for variation in beliefs about the nature of the universe, creation and human spirituality. Gray systematically explains seven distinct forms of atheism that have been embraced throughout history. A book of remarkable clarity and exposition that illuminates the ways we see ourselves and the world. THE YOGASUTRA OF PATANJALI: A NEW INTRODUCTION TO THE BUDDHIST ROOTS OF THE YOGA SYSTEM by Pradeep P. Gokhale I don't know how many different translations and explanations of the Yoga Sutras I have read. Dozens. Many are confused or confusing, and scholars are increasingly aware of the compiled nature of the text, and how it shows influence from a handful of other systems of thought. Buddhism is among these influences, but deep dives into the Buddhist roots of the Yoga Sutras require a rare combination of expertise. With this new research, Gokhale has provided a huge step forward in our understanding of the philosophical and linguistic roots of the Yoga Sutras. He analyzes works of Abhidharma Buddhism and shows how they explain many aspects of the Yoga Sutras better than traditionally accepted narratives. This is a scholarly work, full of difficult history and terminology, but worth it for anyone with a serious interest in yoga history or the Yoga Sutras in particular. WHY WE SLEEP by Matthew Walker This book was recommended to us by several people over the past few years until it became impossible to ignore. And it was worth it! We even wrote a blog about it. The book begins with the obvious-in-hindsight revelation that sleep is vital. It is not a passive state of nothingness that can be shortened or neglected. Rather, it is a very active state for many systems of the body, especially the brain. Walker explains the structure of sleep and its impact on things like our memory, physical health and even physical coordination. This is a book with practical, everyday implications that can make anyone's life better. THE CHAKRAS by C.W. Leadbeater Earlier this year, as we were doing research for a workshop series on the Yogic Body, we read a handful of books about the chakras from the early 20th century, including this one. Leadbeater was a prominent Theosophist, a highly influential group that shaped modern conceptions of yoga and spirituality. This book from 1927 is remarkable as a vivid capsule of the time. Leadbeater claimed that he could see the chakras, and he painted them beautifully. I find these paintings to be among the most remarkable elements of 20th century yogic history because, aside from being lovely, they show the break-neck speed of change in conceptions of the yogic body. Here, in the 1920s, there were seven chakras associated with parts of anatomy. But they were not yet rainbow in color nor linked with psychological traits as they came to be in the 1970s. HOW JESUS BECAME GOD by Bart D. Ehrman Along with our study of yoga history and the history of religion in general, both Ida and I have been increasingly reading about the history of Christianity. It is fascinating for the same reason as all history — our ideas change rapidly along with the cultural needs of the time. This book by Ehrman explores the early centuries after the death of Jesus, and how the story of Jesus changed, turning him from a preacher or even a prophet into the only son of God himself who rose from the dead. It is full of scriptural quotations and explanations alongside historical analysis. And it is quite readable, which is not something one can often say about a work of scholarship like this. BREATH by James Nestor

I never thought someone could write a compelling story about breathing, something we all do thousands of times each day. But Nestor has crafted a surprisingly interesting narrative around his own research into breathing anatomy, physiology and history. Where it falls short of a scholarly history or a medical anatomy text, it more than makes up with its humor and readability. This is a book that anyone can and should read to have more understanding and appreciation of the most fundamental function of life — breathing.

0 Comments

Nowadays, ujjayi is a term that is often used in yoga classes. It is said that ujjayi creates a snoring sound, focuses the mind, slows the breath, heats the body, or is a constriction in the throat. Let's examine ujjayi from a historical lens and see if these ideas can be supported. HATHA YOGA'S UJJAYI In the 15th-century text the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP), the instructions for ujjayi are as follows: Close the mouth. Slowly draw the breath through both nadis so it resonates from the throat to the heart. Form the kumbhaka as before. Exhale the prana through the Ida. This kumbhaka called Ujjayi can be done walking or standing. It removes phlegm diseases in the throat, increases digestive power in the body, and destroys dropsy and diseases of the nadir and of all bodily constituents. (2.51-53) There are quite a few terms that may be confusing, but essentially this instructs the practitioner to inhale through both nostrils and exhale out of the left side. This is not what we have come to know as ujjayi today, in which we exhale through both nostrils or even out the mouth. However, as we will see, ujjayi with the exhalation out the left nostril is a consistent instruction up until very recently. The exact same passage from the HYP is found in the Hatharatnavali from the 17th-century. This translation states that we should breathe "with a frictional sound" rather than using the word "resonates" as found in the HYP translation. Either of these instructions could support the idea that ujjayi is practiced with a snoring or whisper sound. Another text of hathayoga, the Gheranda Samhita states: Draw in air through both nostrils and hold it in the mouth. After drawing it through the chest and throat, hold it in the mouth again. After rinsing the air around in the mouth, bow the head, perform Jalandhara, and hold the breath for as long as is comfortable. After performing the Ujjayi kumbhaka, the yogi can succeed in everything he does. (5.64-66) Here we have instructions to breathe in through both nostrils and move the air around in the mouth. However, the next passage is potentially where the mix-up happens. The instructions then say to "perform Jalandhara". The instructions for Jalandhara mudra are to "contract the throat and put the chin on the chest." We would argue this does not mean "constrict" the inside of the throat, but rather contract the muscles on the front of the throat to put the chin on the chest. (This is in line with the common understanding of jalandhara.)

Ujjayi requires Abhyanatara Kumbhaka, that is Kumbhaka practised after deep inhalation. The first thing that demands our attention is the complete closure of the glottis. This thoroughly shuts off the passage to and from the lungs. The second thing is the practice of Jalandhara-Bandha and the third is shutting of the nostrils.....When Kumbhaka is to end, first relieve the pressure from the left nostril, then unlock Jalandhara-Bandha and afterwards partially open the glottis. Rechaka is done through the left nostril. Here again we have the instruction to hold the breath after the inhale. The throat lock is applied to keep the air in, and here the nostrils are also closed. Again, exhalation is done through the left nostril. We see the move toward teaching the throat constriction with anatomical language. Kuvalayanada clearly states to close the glottis. In 1931, Swami Shivananda instructs: Inhale through both nostrils in a smooth uniform manner till the breath fills the space from the throat to the heart with a noise. Retain the breath as long as you can comfortably do it and then exhale slowly through the left nostril by closing the right nostril with your right thumb. Shivananda writes that ujjayi "removes the heat in the head" yet he also says that it increases the gastric fire. Whether this supports removing heat or building heat is up for debate. Either way, this is the only mention of heat in all of the sources examined here. It is no surprise that Shivananda's disciple Swami Vishnudevananda in his popular book The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga instructs the practice in the same way. Vishnudevananda quotes the HYP. The benefits he lists for ujjayi suggest it removes "phlegm from the throat" and prevents a handful of diseases. He says nothing about internal heat. In 1962, Patthabi Jois mentions ujjayi only in a list of pranayamas that pregnant women can do in Yoga Mala. There is no description given.  Iyengar teaching ujjayi in Light On Yoga - 1966 (p. 442) Iyengar teaching ujjayi in Light On Yoga - 1966 (p. 442) In Light On Yoga from 1966, Iyengar teaches ujjayi as follows: Take a slow, deep steady breath through both nostrils. The passage of the incoming air is felt on the roof of the palate and makes a sibilant sound (sa). This sound should be heard. Fill the lungs to the brim....Hold the breath for a second or two....Exhale slowly, steady and deeply, until the lungs are completely empty. As you begin to exhale, relax your grip on the abdomen. Iyengar instructs that mula bandha is to be used and states that "ujjayi pranayama may be done without the Jalandhara Bandha even while walking or lying down". Iyengar removes the instruction to exhale out the left side only, but he maintains the use of jalandhara bandha and emphasizes the sound of the breath. Though Iyengar shortened the retention to just a few seconds, there is still a retention. It is not a smooth or even breath cycle. Ujjayi is rarely referred to in the Ghosh lineage. In Gouri Shankar Mukerji's 84 Yoga Asanas from 1963, it appears only in mention of additional pranayama practices and is one in which "longer pauses are inserted between the inhale and exhale". RECENT DESCRIPTIONS OF UJJAYI IN YOGA Very recent passages such as David Swenson's in his 1999 book Ashtanga Yoga explain: This unique form of breathing is performed by creating a soft sound in the back of the throat while inhaling and exhaling through the nose....The main idea is to create a rhythm in the breath and ride it gracefully throughout the practice. This sound creates a mantra to set the mind in focus. In 2006, Gregor Maehle writes: Ujjayi pranayama is a process of stretching the breath, and in this way extending the life force. Practicing it requires a slight constriction of the glottis....Start producing the ujjayi sound steadily, with no breaks between breaths. These passages don't refer to creating internal heat, but the sound created is given deep importance. It is surprising to see ujjayi become an even breathing technique. However this makes more sense if we look at descriptions of breathing techniques in systems outside of yoga. BREATHING IN PHYSICAL CULTURE & GYMNASTICS JP Mueller was a Danish instructor of gymnastics and physical culture in the early twentieth century. Mueller's "System" manuals deeply informed the practices of modern physical culture, and in turn, modern yoga. (For more on this see Mark Singleton's Yoga Body.)  "The Correct Pose for Inhalation - Front View" JP Mueller's My Breathing System - 1914 "The Correct Pose for Inhalation - Front View" JP Mueller's My Breathing System - 1914 Instructions in Mueller's My Breathing System are more in line with today's descriptions of ujjayi which emphasize rhythmic breathing. Mueller writes: I do not advocate any breath-holding exercise. It must also be remembered that it is not only the action of the lungs and heart which is disturbed by holding the breath. What stimulates the stomach, liver, bowels and intestines is just the internal massage produced by the movements of the lower ribs and the diaphragm, when full, deep, correct breathing is performed. Furthermore, there is emphasis on the importance of rhythmic breath for vitality as early as 1892. Genevieve Stebbin's writes in her book Dynamic Breathing and Harmonic Gymnastics: ...the truth that deep, rhythmic breathing combined with a clearly formulated image or idea in the mind produces a sensitive, magnetic condition of the brain and lungs, which attracts the finer ethereal essence from the atmosphere with every breath, and stores up this essence in the lung-cells and brain-convolutions in almost the same way that a storage battery stores up the electricity from the dynamo or other source of supply, and is held in suspension amid the molecules forming the cellular tissue as a dynamic energy, possessing both mental and magnetic powers, always ready for use whenever required. It is here that we see the distinct link of breath to cultivation of life force in the body. Where hathayoga texts suggested ujjayi removes phlegm, in sources outside of yoga we see the focus on building vitality. This is still common in yoga classes today and is another display of the outside influence on modern yoga. CONCLUSIONS Early- to mid-20th-century conceptions of ujjayi in yoga instruct retention of the breath. Most instruct the exhalation out of the left nostril, with the exception of Iyengar. While there is a sound and constriction of the throat associated with the practice, that constriction often means jalandhara bandha, or tucking the chin to the chest. There is no mention to creating internal heat except when Swami Shivananda mentions gastric fire and removing heat from the head. With the exception of Iyengar, all of these descriptions follow the hathayoga instructions quite closely. Ujjayi has undergone quite a transformation in the centuries it's been taught. If we look to instruction on breathing practices from systems outside of yoga such as physical culture and gymnastics, we get a glimpse at how ujjayi evolved into what it is today. Sources: Akers, Brian. 2002. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika. (p. 45-46)

Gharote, Devnath & Jha. 2014. Hatharatnavali (p. 46) Iyengar, BKS. 1966. Light On Yoga. (p. 442) Jois, P. 1962 (in Kanada, 1999 in English ) Yoga Mala. (p. 67) Kuvalayananda, S. 1931. Pranayama, (p. 76-78) Maehle, G. 2006. Ashtanga Yoga. (p. 9) Mallinson, J. 2004. The Gheranda Samhita. (p. 62, 105) Mukerji, GS. 2017. 84 Yoga Asanas. (p. 3) Mueller, JP. 1914. My Breathing System. (p. 17) Shivananda, S. 1931. Yoga Asanas. (p. 85) Singleton, M. 2010. Yoga Body Stebbins, G. 1892. Dynamic Breathing and Harmonic Gymnastics. (p. 53) Swenson, D. 1999. Ashtanga Yoga. (p. 9) Vishnudevananda, S. 1960. The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. (p. 249) In a normal year we leap into action in September, traveling all over the US and Canada to visit studios and lead workshops. We spend a weekend in each city so that the yogis there can take real time immersed in study and practice. But this is not a normal year. Yoga studios are either closed completely, operating with severely limited schedules and capacity, online, or fighting for their lives as a business. Which of course means that yoga practitioners are left wondering how to practice and how to make progress.

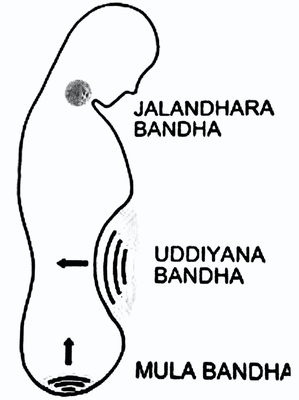

This September we will run two four-week workshop series online. Our goal is to enable yogis to study, learn and practice as they would if they attended an in-person workshop. When we are in-person we usually practice for 6-8 hours per day. But that would be pretty terrible in an online setting, so we will break it up into two-hour chunks. One each Saturday, every Saturday in September. BREATHING & PRANAYAMA The first workshop series is about pranayama. More people ask us about this than anything else. It is a natural and important progression from posture practice, since once we can control the body, the breath is next. In two-hour sessions we will walk you through how the body breathes, the effect it has on the nervous systems and body chemistry, and what it means for yogic practice. Part of the sessions will be in lecture format and part will be practicing these ideas and techniques. Each week you will get a little homework practice that will take 10-15 minutes per day. In this way you will build your understanding and experience with pranayama, yogic breath control. By the end of the month, you will have the knowledge and skills to make progress on your own for 1-2 years. More details about the schedule and sign-up are here. BUILDING BALANCE The second series is a class series about Balance. We will lead you through 90-minute classes designed to build the strength, awareness, control and concentration that are needed to balance well. No lecture portion for these classes, as they are purely experiential. More details about the schedule and sign-up are here. BOTH Of course, you can sign up for both. The two are intended to work together and complement each other. Our goal with these is exactly the same as when we travel to meet you in-person: to provide the opportunity to learn and deepen your practice. You may be a dedicated daily practitioner or someone who goes in fits and starts. Our hope is to inspire you in your practice and give you the knowledge and tools to make progress! Mula bandha is a somewhat common technique in modern yoga. It is generally accepted that this technique, which means 'root lock', is a contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor. Some interpret this to be the perineum, the anus, or a combination of the muscles in the pelvis. The anatomical specifics of how and when to do mula bandha are not the goal of this article. Today we are looking at where the practice comes from, and perhaps why it was developed. The instruction of mula bandha dates back to the early days of Hathayoga, around the 12-13th centuries CE. At this time, Hathayoga was gradually forming out of the tantric beliefs of Buddhism and Shaivism. Alchemy, the attempt to forge new substances, was widely accepted, and the spiritual seekers began practicing an 'inner alchemy' where the magic happens inside the body of the yogi. According to this alchemical belief, the inner elements of a person could be forged to create immortality, divinity or great power. As Shaivism (the worship of Shiva) became more prominent in Hathayogic teaching, the concept was related specifically to the awakening of kundalini, a latent power of pure consciousness. The way that kundalini is awakened is by manipulating the 'winds' of the body, some of which naturally go up while others go down. In Hathayoga, mula bandha is specifically intended to take the downward-moving 'wind', called apana, and push it upward. Once the apana wind is turned upward, it is fanned with the abdomen to heat it. Then it combines with the upward wind, called prana. The combination creates an inferno that awakens and raises kundalini. Below is an excerpt from the Hathapradipika, perhaps the best known text on Hathayoga:

As you can see, mula bandha is specifically intended to turn apana upward, where a whole series of events follows. This description of mula bandha is present in almost all the texts of Hathayoga. Here is one other, from the Goraksasataka, translated by James Mallinson. I include it because it is pretty elaborate and well-explained:

This explanation continues to the modern day, though it is rarely incorporated in common yoga posture classes that remove esoteric or spiritual overtones. For obvious reasons, a simple muscular contraction is far easier to teach and understand than a detailed metaphysical system of bodily winds and latent spiritual energy. Nonetheless, Swami Sivananda and his students like Vishnudevananda explain mula bandha similar to the older Hathayogic way. Iyengar, in Light On Yoga, foregoes the apana-kundalini approach and explains mula bandha a little differently. He initially explains the bandhas as closing off "safety valves", which is reminiscent of the old way. But he goes on to interpret the term mula bandha as follows: mula means 'source', and bandha is 'restraint'. So mula bandha is the restraint of the mind, intellect and ego. This recalls Patanjali's famous definition of yoga at the beginning of the Yoga Sutras. Here is what Iyengar writes in Light On Yoga:

We don't think it's a stretch to say that this is a reinterpretation of the meaning of mula bandha. Separately, in modern practice and teaching mula bandha is sometimes taught as a physically stabilizing technique, again quite different from its original iteration.

What does it all mean? Like so many things in yoga, the purpose of the practices can change so that they become unrecognizable. Does that make them less effective, useful or valuable? Perhaps. We think it is worth asking ourselves why we do what we do. What are the underlying reasons? Personally speaking, we do not hold the belief that our bodies are populated by 'winds', as was apparently the belief for some time during the development of Hathayoga. We attribute our 'digestive fire' not to actual fire but to hydrochloric acid in the stomach. And we attribute urination and excretion not to downward-moving apana wind but to peristaltic movement of the intestines and contraction of the sphincters. Do these beliefs make something like mula bandha anachronistic? We think that they do. Along with the introduction of modern physical practices, a lot has been lost in the world of breath control practices as they were documented through yogic texts for many hundreds of years. Pranayama is most easily translated as breath control, but “prana” means one’s life force. Pranayama is therefore, the control of one’s life force as accessed through the breath.

There are many benefits to controlling the breath. These benefits continue to be brought to the forefront through scientific study. Benefits range from relaxation to potentially suppressing tumor growth in the body. While the studies are magnificent in their potential, the most powerful reason to cultivate the breath in yoga is because of its intermediary relationship to the body and the mind. When we access and manipulate the breath, we use two different parts of our brain. We also can access the two parts of our autonomic nervous system by changing how we breathe. If that wasn’t enough, we can also choose which nostrils we breathe through and stimulate our olfactory nerve which has a direct relationship with our brain. Many of us might question the necessity of these types of practices since our breath is an automatic function. However, it is easy to make the judgement that breath manipulation is unnecessary when we have not experienced the results. Once you realize breathing can reduce stress, focus the mind, and possibly suppress cancerous tumors, it seems an obvious practice to undertake. When we strengthen our awareness of the body through asanas, we are mostly concerned with our muscles, bones and structural tissues. We get stronger muscles, and ease muscular tension. The benefits often translate into other systems of the body which result in things like better circulation or digestion. However it is not until we get into pranayama that we experience the body on a deeper plane. The awareness we get from breathing is the awareness of our nervous system. It is a deep and profound level of awareness that leads us to a level untouched by most: experiencing the mind. Most of the time we experience our thoughts. We never think about thinking, we only react to our thoughts. We get lost in the result of our thoughts, but not in what caused them to begin with. A very common example of this phenomenon involves the idea of a movie and the screen on which the movie is projected onto. When we watch a movie, we know it is not real. The screen is blank before the movie begins and is blank after the movie finishes. We just accept this. However our minds are no different! They are blank before a thought arises and blank after the thought finishes. The problem is that we mistake the thoughts for reality. Through stillness, we can learn to identify the “movie screen” of our minds as reality, not the fleeting thoughts that project onto our mind. Pranayama, and working to still the breath, is the gateway into stillness of the mind. Most yoga practitioners know pranayama is the skill and art of breath control. But the breath can be a difficult animal to tame.

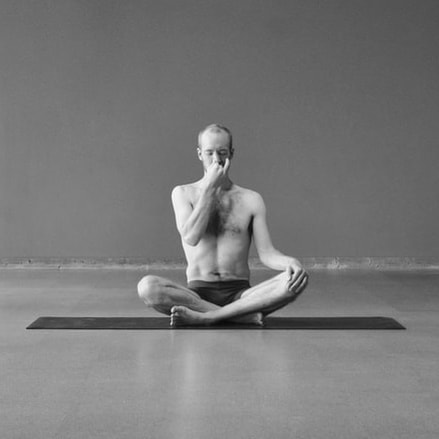

When we start to do breathing exercises, it can make us feel claustrophobic or anxious. Our breath is largely governed by the autonomic nervous system, and when we control it consciously we can run head-on into the body's habits and patterns. The Hathapradipika says, "like elephants and tigers, the breath must be controlled slowly." (II.15) When practicing pranayama, sit on the ground so that your legs are crossed and your torso is upright. Sit up nice and tall. If it's impossible to sit on the ground, you can sit in a chair. Make the body still so that the breath becomes the center of your focus. Always stay relaxed. If the breathing makes you anxious or panicky, stop immediately. Here are two simple and safe practices to start: 1) Even Counting, and 2) Alternate Nostril. EVEN COUNTING This technique is so simple that you may do it already in some yoga classes. It involves making the inhale and the exhale even in length. A great length to start with is 3 or 4 seconds each. So inhale for 3 or 4 seconds, then exhale for 3 or 4 seconds. Stay very relaxed and continue this for a few minutes. This technique has the effect of synchronizing the breath with the nervous system and the heart rate. After a minute or so you will feel quite calm, peaceful and centered. ALTERNATE NOSTRIL When starting with this technique there is no need to control or count your inhales and exhales. You can let the breath come in and out naturally and relaxed. Use your right thumb to close your right nostril. Inhale calmly through the left nostril. Then use the ring and pinky fingers to close the left nostril, open the right, and calmly exhale out of the right nostril. Then inhale through the right nostril. Then close the right nostril, open the left, and calmly exhale out of the left nostril. Continue in this fashion for about 5 minutes, staying as relaxed as you can. As mentioned above, controlling the breath can bring up anxiety or a sense of panic. If you feel this, stop immediately. The goal of these beginning breath practices is to stay absolutely calm throughout. They should give you a growing sense of well-being and peace, not anxiety. Once you can do these exercises with control, ease and calmness, you are ready to move on to more difficult practices. Western medicine has known for decades (and yogis have known for thousands of years) that controlling the breath is a powerful tool to access the mind.

Now we know that this connection is largely via the autonomic nervous system. Every time we inhale, the heart rate goes up a little. And every time we exhale, the heart rate goes down a little. This is controlled by the two parts of the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic, respectively). In everyday life we tend to get overwhelmed with tasks and stress, which causes an overstimulation of our "active" nervous system. Our heart rate stays a little higher, we have trouble relaxing and we feel this as stress. In recent years breathing techniques have been making their way into the popular culture, with everything from heart rate variability monitoring devices to smartphone apps that help you control the breath. This includes a great new app called the "Breathing App" developed by yogi Eddie Stern and Deepak Chopra. The basis of their app is so-called "resonance" breathing, a specific, regular tempo that has benefits like lowering the blood pressure, improving heart rate variability and positive applications for anxiety and depression. The tempo is not difficult to achieve and is accessible for nearly every person. It ranges from breathing 5-7 times per minute as opposed to our normal rate that is closer to 15 times per minute. (5 times per minute is 12 seconds for a complete inhale & exhale. 7 times per minute is about 9 seconds for a complete inhale & exhale.) We recommend the "Breathing App." It is free and quite simple to use. It requires nothing more than a couple minutes of your time to breathe, regulating your inhale and exhale to achieve the coherence and resonance between the breath, heart and nervous system. Hopefully it will bring a little bit of peace, relaxation and well-being. Why do we, as yogis, practice physical postures?

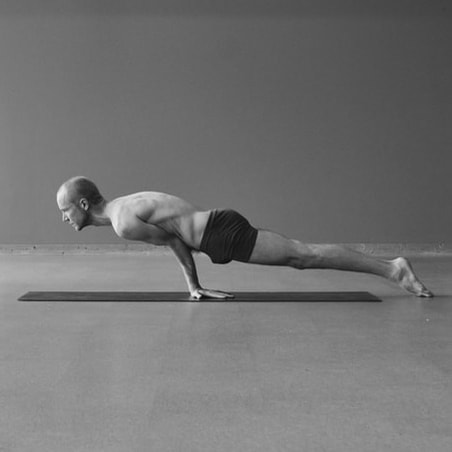

Depending on your goals, there may be a handful of answers to this important question. The exercises may increase your flexibility, increasing your ability to move the body without pain or limitation. They may help you relax, spending a little time each day focused only on your breathing and forgetting about your stress. They may help your balance, strength, blood pressure or sleep. At the center of all these motives is the spine, perhaps the single most important communication pathway of our body and mind. We can live without our arms and legs, but we cannot live without our spine. It provides structure, protection and support for our heart, lungs, organs and head. Almost every signal sent from around the body, from the fingers to the toes, makes its way to the central nervous system by way of the spinal cord. And almost every command about balance, movement or breath also travels via the spine. So every exercise, whether of the feet, arms, hips or abs is also an exercise of the spine. Even breathing exercises and meditation require communication through the spinal cord as we control our ribs, abdomen and posture. Paramhansa Yogananda called the spinal cord a "lightning rod for the divine." Our practices should contain plenty of attention to the health and function of the spinal column (the structural part) and cord (the nervous system part). We should keep the muscles of the spine strong and mobile, as well as doing what we can to protect the bones and discs strong; plenty of forward bending, backward bending and twisting. And we should also keep our awareness on the communicative aspects of the spine: its nerves. As one of our teachers said: "The arms and legs assist the posture. Every posture is in the spine." If you are thinking about trying yoga or have just begun, there are a few simple things to keep in mind during your first few classes.

1. KEEP YOUR BREATHING CALM As you do different exercises, you may notice that you are holding your breath or grunting. This isn't inherently bad or dangerous, but it illuminates tension and weakness in the body. Try to do each exercise and movement with the breath as smooth and calm as possible. Some practices will be easier than others! 2. IT'S A MARATHON, NOT A SPRINT It is easy to try to do everything perfectly in the first couple classes. But the practice of yoga unfolds over the course of years. Too often, new students work really hard for one or two weeks before burning out and disappearing, never to return. It is better to be calm and gentle in your practice. Let it develop slowly and you will make far more progress. 3. KEEP AN OPEN MIND You may be asked to do things that you've never done before: unusual breathing patterns or body positions. (Luckily, as yoga has become popular more and more people are familiar with the basic practices.) Trying something new always feels awkward, but give it a chance. 4. DON'T DO ANYTHING THAT HURTS At the beginning your body will be stiff, and some of the exercises may be painful. Err on the side of gentleness, especially if you're unsure. The teacher may instruct that the exercise is uncomfortable and that may help you relax. But if you have pain it is best to back off. You will make more progress if you can keep your body and mind relaxed. Over time your strength and flexibility will improve along with your understanding. There is no need to force it at the beginning. 5. ASK THE TEACHER As you go through the class and the teacher asks you to do things you've never done before, there will probably be a lot of questions that pop into your mind. Am I doing this right? My such-and-such hurts, should that be happening? I don't feel anything...? When you are unsure of what you're doing or why, don't be afraid to ask the teacher after class. The teacher is there to help you learn and progress, so they will be happy to help.  Sometimes yogis talk about "stuck energy" or "moving the energy" of the body. According to some yogic texts, especially in hathayoga, there are subtle channels in the body along which energy moves. It is difficult to determine whether these channels are intended to be purely mental visualizations, descriptions of what we call the nervous system today, or a separate entity altogether. The details of this vast topic are best saved for another time, but here are 5 postures and exercises that are great and moving and affecting the energy: 1. TWISTING TRIANGLE Pictured above, this posture goes right to the areas where most of us feel "stuck," the chest, the hips and the breath. By bending forward and then twisting the body, the posture feels like it makes everything tight. The trick is to release tension with short, calm breaths and a relaxed face. This posture also challenges the balance, which focuses the mind and enables a deeper experience.

|

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed