|

The second abdominal engagement - engage the back, relax the front - is the opposite of the first.

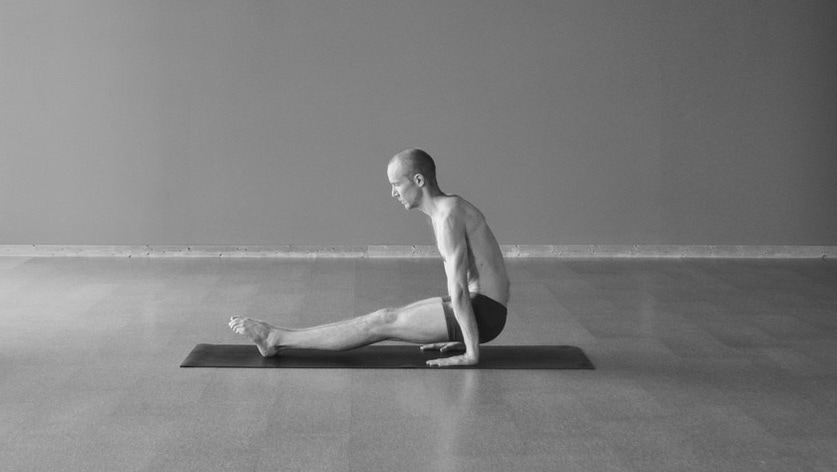

To bend the spine backward like in Cobra, Camel or the Back Sit-up (pictured above), the muscles on the back of the body must engage and shorten. These largely include the erectors of the spine, which are aided by pulling the shoulder blades together (trapezius and rhomboids). Pulling the shoulder blades together especially helps to stretch the chest and shoulders which are commonly tight from using computers and hunching forward as much as we do. THE HARD PART The muscles of the front must be completely relaxed. Believe it or not, this is actually the hard part of backward bending. The abdominal muscles, namely the rectus abdominis (6-pack) needs to relax to let the spine bend backward. If it is tight or engaged, backbending will be difficult or even detrimental. THE GLUTES & PELVIS Any backbend that is done lying on the belly (like the one pictured above) benefits from engaged glutes (butt muscles) to stabilize the pelvis and release the psoas, enabling the spine to bend completely. It feels like reaching back strongly through the feet. On the other hand, any backbend that is done upright like the Standing Backbend (Half Moon) or Camel, should have soft glutes until you've come into the depth of the posture. If you engage the glutes from the start to push the hips forward, your abdominal muscles will probably engage too, and this will prevent your spine from bending. This type of muscular action encompasses (starting top left) Salute to the Gods & Goddesses, Half Moon, Standing Bow, Separate Arms Balancing Stick, Dancer (variation), Camel, Cobra, Full Locust, Bow, Wheel, and full backbends like Full Cobra & Pigeon.

0 Comments

There are 6 main abdominal engagements in yoga postures. They encompass forward bending, backward bending, a straight spine, side bending, twisting and abdominal relaxation.

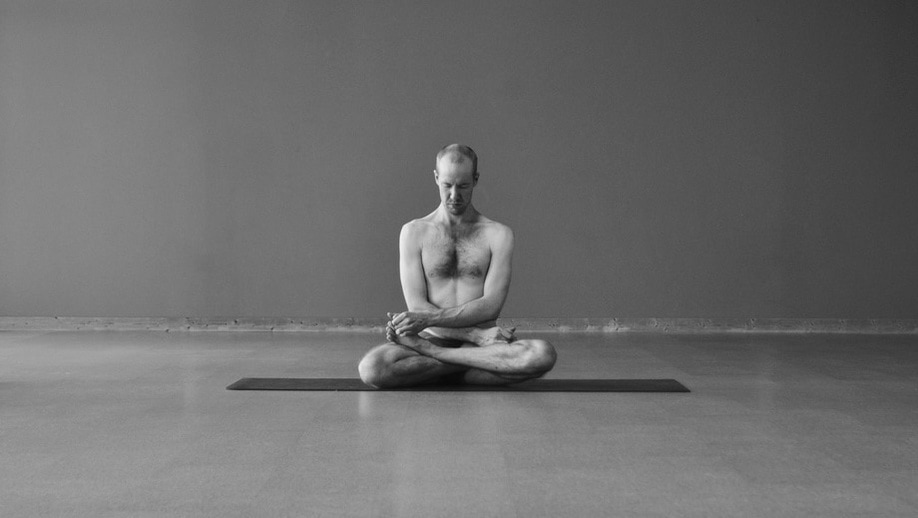

1. Engage the front, relax the back (forward bending). 2. Engage the back, relax the front (backward bending). 3. Relax both the front and the back (abdominal relaxation). 4. Engage both the front and the back (straight spine). 5. Engage the right, relax the left (side bending). 6. Engage the right oblique, relax the left oblique (twisting). FORWARD BENDING To bend the spine forward like in Rabbit Pose (pictured above), the muscles in the front of the body must engage and shorten. These include the sternocleidomastoids in the neck, to bend the head forward, and the rectus abdominis (6-pack) in the abdomen, to bend the lower spine forward. There aren't really muscles in the ribcage to bend the mid-spine forward, but a strong exhale can help make the ribs compact and create a small forward bend there. The muscles of the back must be completely relaxed in a forward bend. This is how the spine bends forward. If the back muscles are tight, the spine will stay straighter. (The arm balances pictured below don't incorporate the neck into the forward bend. Instead, the head is kept lifted for counterbalance.) This type of muscular action encompasses (starting top left) Salute to Gods & Goddesses; Hands to Feet; Crouching Head to Knee (in the Sun Salute), Standing Separate Legs Head to Knee, Standing Head to Knee, Crow, Crane, Rabbit and Stretching Head to Knee. In 1947, Buddha Bose was in a plane crash. He survived, but badly injured his spine. It marks a turning point in his life, away from physically-centered yoga practices toward spirituality. After this, he made several treks into the Himalayas to visit sacred places.

On one of these trips, he took off his back brace (which he was forced to wear to support his injured spine) to wash in the icy mountain river. He emerged, sat down to meditate and unwittingly went through the rest of the day without the brace. When he finally realized his oversight, he found he had no more need of the support. This and many other stories of Bose's treks to the holy places in the Himalayas are described in his little-known book "Holy Kailas." There is only one known copy left in the world, in the Indian National Library in Kolkata, India. Chitralekha Shalom, Bose's daughter-in-law who lived, studied and taught with him before his death, writes an interesting blog full of personal and historical stories. She recently wrote about "Holy Kailas." Her blog called Moral Courage, from a phrase suggested to her by Buddha Bose himself, is here. Her Facebook page, also called Moral Courage, is here. If you've ever been to a yoga class, it is likely that you heard the teacher say "Namaste" at the end of class. In the West, this salutation often gets interpreted as "the spirit within me is the same as the spirit within you and all things. This oneness pervades all of existence." This is a specifically non-dualist philosophy/spirituality that sees unity in all of the universe, a philosophy that is central to Advaita Vedanta, one of the schools of Hindu thought.

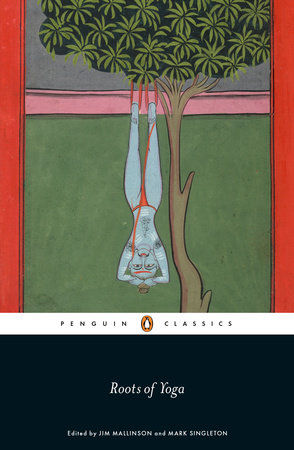

The Yoga Sutras by Patañjali, on the other hand, espouse a dualistic philosophy wherein the 'consciousness' (purusha) is separate from 'matter' (prakriti). Furthermore, there is a separate God figure, Ishvara. The idea that "all is one" is simply not present. Quite the contrary, since the philosophy of yoga is based on the idea that our suffering will cease only when we realize that our 'consciousness' is different from 'matter,' specifically our body and the objects we experience with our senses. We must acknowledge that these two ideas conflict. They are irreconcilable with each other. And although there are many definitions and philosophies of yoga throughout history, it is important that we realize what ideas we are perpetuating, and that we are careful not to teach ideas that are philosophically incompatible. A new book was released in the US a couple days ago: Roots of Yoga, edited by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton. (You may know Singleton from his book Yoga Body, and Mallinson is perhaps best known for his critical translation of ancient texts.)

WHAT IT IS The book provides translations and organization of "core teachings" throughout the history of yoga, including lots of texts in scholarly translation for the first time. It is organized by chapter into the "limbs" of yogic practice, including Posture, Breath-control, The Yogic Body, Yogic Seals, Mantra, Samadhi, Yogic Powers and Liberation. Each chapter includes source texts that deal with the specific topic. WHY IT'S IMPORTANT This book doesn't attempt to "explain" or modernize any of the teachings of yogic practice. It only provides original instructions from old texts. And while the texts may differ and even contradict each other at times, it is extraordinarily valuable to see what they actually say. This book brings scholarly translation of rare yoga texts into an accessible and organized format. It is widely available anywhere books are sold, including Amazon. Tiger (also called Byagrasana, Forearm Balance or Pincha Mayurasana) is a difficult posture that involves balancing the body upside down using only the strength of the arms and shoulders. In order to do the posture safely and sustainably, we must gradually build strength and coordination in our arms, shoulders and torso.

There are two main elements necessary to do Tiger (pictured bottom right): strength and balance. Strength must be built first; it will be impossible and even dangerous to balance without strength. We start with the Forearm Plank (pictured top left). Quite simply, this begins to teach the shoulders how to carry the body's weight. Next, walk the feet toward the head so that the hips lift up (pictured top center). Notice how this changes the position of the shoulders in relationship to the body. We are gradually moving them toward the position of Tiger. Walk the feet as close as possible to the head (pictured top right). The hips come over the shoulders, placing the shoulders in the proper position for Tiger while still keeping the feet on the floor. Then lift one of your legs straight up (pictured bottom left). This puts more weight into the arms, building strength, and also destabilizes our balance, forcing more balance into the arms. The final preparation works entirely on balance. Lift both feet off the floor and split the legs apart (pictured bottom center). It helps to do this against a wall at first. Splitting the legs lowers the center of gravity, making balance a little easier. As your balance stabilizes, you can slowly lift your legs up and together, until you are balanced in Tiger! On April 15 we pay a portion of our earnings to the government to be redistributed. These taxes are essential to running our society. There are good, bad and difficult yogic concepts hidden within this one day.

Perhaps most yogic (and spiritual) about paying taxes is ridding ourselves of excess. It is no coincidence that every spiritual tradition encourages humility and poverty. By giving up our possessions, we avoid the common problem of mistaking our possessions for ourselves. Even though taxes aren't technically voluntary, we can offer them with that state of mind. We should celebrate the opportunity to support our fellow humans, our environment and community, paying the salaries of our teachers, fire department, police and other government-paid employees. Of course, there are also philosophical challenges to paying taxes. When our government uses public money to fund programs to which we are morally opposed, it turns the greatest benefit (see above) into the greatest frustration. (We must take care, though, that we don't use this as an excuse to hoard our resources.) In conclusion, we have the power to control our state of mind about paying taxes. We could think about it like government oppression, with the state taking our hard earned money. Or we could think about it as an opportunity to support the people and institutions around us. The full version of Palmstand involves lifting the hips and the legs off the ground into an L shape, supported only by the arms. It is difficult to do, but there are a couple of great preliminary steps to help move us in the right direction.

The first step, pictured above, is simply to lift the hips off the ground. Make sure that the hips go BACKWARD between your hands instead of forward. Virtually everyone can practice this. If it seems impossible to get your hips off the ground, or that your arms are too short (they're probably not!), you can put your hands up on blocks at the beginning. Palmstand is hard to beat for its strengthening of the arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen and hip flexors. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed