1 Comment

Bending the spine backward, or "backbending," has myriad benefits to the body and mind. You can do it standing, kneeling, lying on your belly or even on your back. In our culture of sitting in chairs and hunching over a computer or phone, backbending is more important than ever for simple, functional health. Here are 5 reasons to backbend:

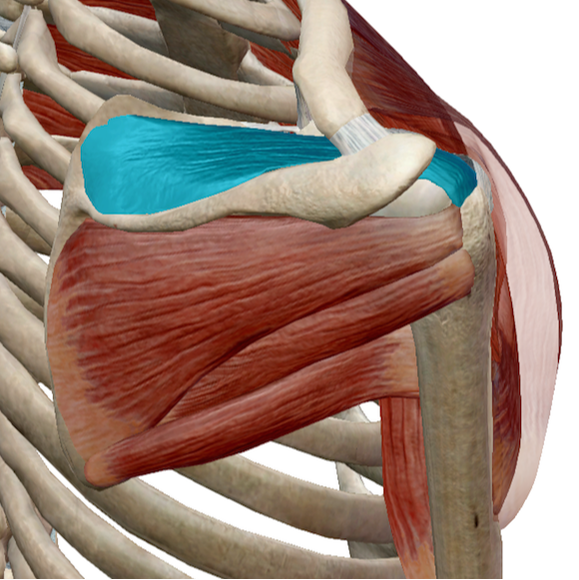

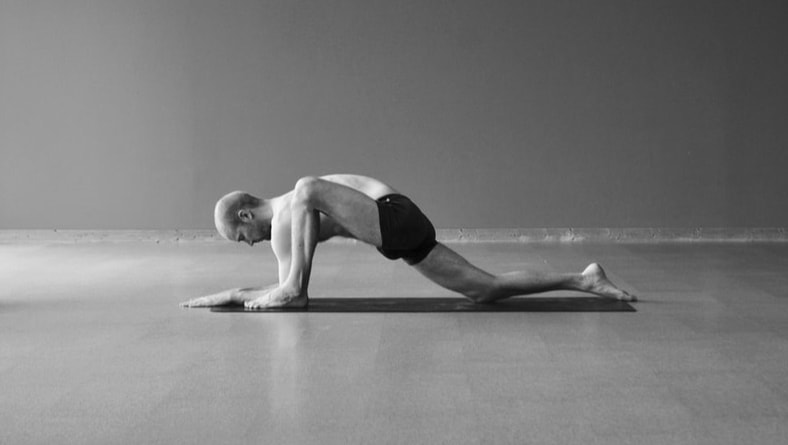

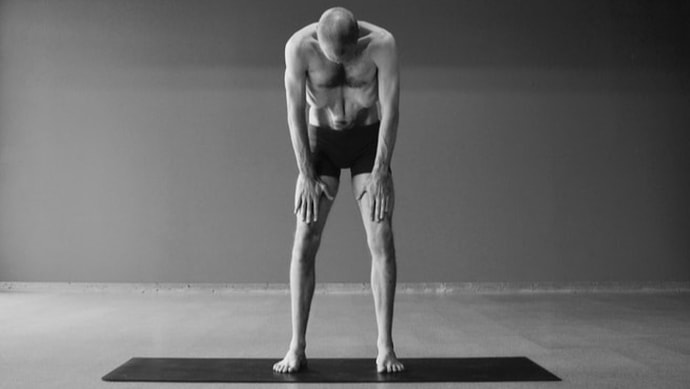

5. Improve your posture: Most of us spend the day sitting and hunching to some degree. Our back arches forward, the chest collapses and the head juts forward. The back muscles get longer and weaker and lose their ability to hold the body upright. Over time this can lead to shallower breath, digestive issues and pain in the chest and back. Doing backbends, especially ones that encourage strength like Cobra, Bow or Full Locust (pictured above), will straighten the spine, lift the chest and head. This goes a long way to preventing all the problems listed above. 4. Energize your nervous system: Bending the spine backward exposes the chest and throat, stimulating our sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight response). For those of us who are lethargic or sluggish, this stimulation has the ability to energize the mind and body. 3. Increase confidence: As explained above, backbending stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, increasing our alertness. If we do backbends while lying on our bellies, we also push the pelvis into the ground, which stimulates the secretion of testosterone. Combining these two---alertness and testosterone---has the general effect of boosting self-esteem and confidence. 2. Improve your digestion: We usually sit or stand with a slight hunch, our ribs pressing down on our bellies. Unless we move around a lot, the intestines (in our bellies) become somewhat stagnant and lose some of their ability to move food through the digestive system and waste out. When we bend backward, this whole area gets stretched, drastically changing the shape of the intestines and abdominal viscera. This often has the effect of unsticking stagnant areas in the gut. 1. Reduce stress: When we backbend, we compress the back of the body where the kidneys and adrenal glands are located. This has the effect of reducing cortisol in the blood, lowering our stress on the chemical level. Several scientific have shown this to be true, one of the great "medical" benefits of practicing yoga and backbending. When taken altogether, these benefits make backbending a powerful tool for mental and physical health. As we deepen our practice and study of yoga, the sheer volume of practices and traditions can be overwhelming. One solution is to stick to the teachings of one tradition and explore them deeply. Even so, I am often curious about why different traditions may have such disparate teachings, all called yoga.

Looking back in history can help clarify the purpose of many practices. We were recently asked if there was ever a point when all yoga was unified around a single set of teachings. Not to my knowledge, unless we go all the way back to the first documented explanation of yoga in the Katha Upanishad, from about 2,500 years ago: "When the five senses are stilled, when the mind Is stilled, when the intellect is stilled, That is called the highest state by the wise. They say yoga is this complete stillness In which one enters the unitive state, Never to become separate again. If one is not established in this state, The sense of unity will come and go." No mention of postures, health, nutrition, stress or flexibility. Only the senses, the mind, the intellect, and a unitive state that arises when they are still. The Katha Upanishad, Part 2, Chapter 2, Verse 10-11. (This post originally published 2/9/2017) We are moving, ridding ourselves of many possessions that we've accumulated over the years, including the house we've lived in for a decade.

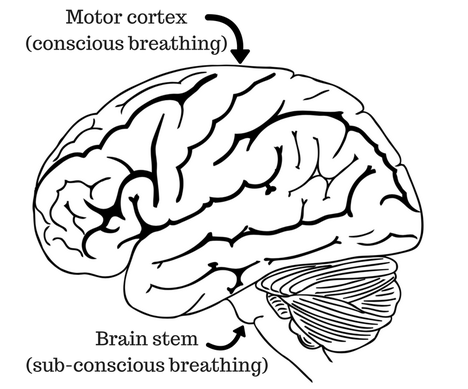

It is surreal to gather all of our belongings into one room, one duffel bag, one truck. To look into the back of a moving truck and see all of our worldly possessions...there are our books, packed away in boxes; there is our bed, wrapped in plastic; there are the lamps that sit by the bed, awkwardly resting on top so they don't break. It is a powerful reminder of how separate we are from the things we own, even though we often think of those things as inherent to our identity. The yogis would say, quite simply, "possessions are not the self." It seems obvious when you say it like that. Of course my possessions are not who I am. But when my possessions are separated from their usual place in my life, I feel their pull acutely. Especially the house itself. The house has given me a place to sleep, study, think, write, read, relax and play with our dogs. It has gradually become inextricable from the way I live and even the person I am. It may be inevitable, but as a yogi I see the danger there. And as we pack up our belongings and wave goodbye to the house, I feel the uncertainty within me: "who am I now?" Of course, on the deepest levels I am no different than I was a day ago or a month ago or, depending on your beliefs, since the beginning of time. But my worldly, human life is undergoing a huge change. It is a challenge for me as a yogi, to navigate this with at least part of my mind on my unchanging, deepest, truest self even as my entire outer world transforms. Most of us know that our breath functions automatically most of the time. This function---breathing without thinking---is controlled by the autonomic nervous system in one of the oldest parts of our brain: the brain stem, located at the base, where the spinal chord turns into the brain.

Most of us also know that we can control our breath consciously, choosing the speed at which we breathe and even stopping it altogether, for a short while at least. This conscious control of our breath is done by the somatic nervous system, the part that controls voluntary functions like walking, writing or playing baseball. It is located on the surface of the brain at the very back of the frontal lobe, in a place called the motor cortex. Whenever we consciously control our breathing, the motor cortex overrides the brain stem. This process takes a lot of effort from the brain, which is why it has the effect of focusing us. As an experiment, try to control your breath while doing a math problem in your head. It is difficult. When we consciously control the breath, the brain becomes still. This phenomenon is one of the key principles of pranayama (breath control) and even the most simple breathing exercises. Even for a true beginner, counting the breath or trying to control it at all calms the mind and leaves them feeling very focused. Uddiyana and Nauli are traditional yogic practices. They date back more than 500 years to at least the Hatha Pradipika.

To do Uddiyana, one holds the breath out and then expands the ribcage as if inhaling. What results is a vacuum in the abdomen which sucks the belly, intestines and organs up. Uddiyana means 'flying up.' "This practice is called Uddiyana because the diaphragm is made to fly up from its original position and held very high in the thoracic cavity." (Yoga Mimamsa, Vol. 1, Oct. 1924) In the early 1920s, Swami Kuvalayananda began a school and laboratory, using modern scientific equipment to test traditional yogic practices and publish the results. His newsletter is Yoga Mimamsa, which started in 1924 and continues today. The first edition was dedicated to the study of Uddiyana. They performed two ground-breaking studies, one involving early X-Ray technology to view the intestines, and the other measuring the internal pressure of the abdominal cavity during Uddiyana. "This exercise has been studied under the X-Ray. Very interesting and valuable data have been collected. Two X-Ray experiments are published...and an article discussing the therapeutic value of this Yogic practice is included..." (ibid.) The pictures above are from the 1960s, when Dr. Gouri Shankar Mukerji performed a similar experiment. These pictures are much clearer than the ones from 1924, which is why we post them here. The x-rays from 1924 are cloudy and difficult to discern. In the above pictures, one can clearly see that Uddiyana pulls the intestines and organs up into the thoracic cavity. The second test measured pressure in the intestines and rectum during the practice. They found that internal pressure is reduced, creating a partial vacuum. "As soon as the muscles were moved for Nauli, the mercury fell through 40 mm. indicating a clear partial vacuum." (ibid.) The discovery of this vacuum was significant, since scientists of the time hypothesized that Nauli reversed the peristaltic movement of the intestines, which would be detrimental to health. The discovery of the partial vacuum refuted this idea. Kulvalayananda named his discovery the "Madhavadasa Vacuum," after his esteemed teacher. When we are new to any given discipline, it is easy to be a sponge. We eagerly soak up the information presented to us by teachers and books. As we become more knowledgable, we are more likely to become closed off. We are sometimes justified in our confidence and skill, and it can lead us to skepticism and rigidity.

It is admittedly difficult to stay open and humble as we learn more and our experience grows. There are times when you will know more than your teachers, and times when you will know your teachers to be wrong. The danger comes when we assume that we know more than others and entrench ourselves in our current level of knowledge and belief. The way around this is (temporary) openness and acceptance. When you are in the position of the student (which is more often than you think), listen and process, accept the knowledge temporarily. Develop a short-term reservoir for new knowledge where all the teachings can go unedited. Afterward, take the time to research and confirm. Some of the teachings will hold up, others will not. The stuff that works will go into your long-term knowledge bank, the stuff that doesn't gets discarded. The more skeptical we are, the less likely we are to learn. We will simply hold onto the status quo and reject any new information that does not confirm our current state. The art of being a student, the art of learning is putting aside skepticism for awhile, no matter how justified it may be. Put yourself in the presence of good teachers, and then trust them to give you good information. As a yoga teacher I often hear students say that they fall asleep in Shavasana. This is a pretty common thing. We hear the snoring of one or more students quite clearly as they break the silence of relaxation at the end of a practice.

As a practitioner, this isn’t something that I often struggle with. I am usually able to relax quite deeply without actually falling asleep. Recently, however, I’ve personally experienced this very phenomenon. A few months ago, Scott and I took an intense course. We began at 4:30am everyday (even on our day off!) and ended around 10pm. The day was pretty much spoken for, although I would sometimes catch a 10 minute nap when I had the chance. After keeping up this schedule for a few weeks, I was exhausted. At around the same time in the course we started adding in Yoga Nidra, or long and deep relaxation. I inevitably would fall asleep. Of course I would try not to, but my system was tired and that was all there was to it. More recently, my life has been extremely busy with commitments. I definitely notice this throughout the days as my body is achy and my mind is slow. But where I notice it the most is in pranayama practice. Pranayama is most often thought of as a breath control practice, but it is even subtler. In English, we don’t have a great translation for “prana” so it becomes easiest to think of this in terms of breath, but it is the practice of working with your life-force energy. Yesterday afternoon, I sat down to do pranayama. I made it through most of my usual routine which consists of three rounds of Kapalbhati and ten or more rounds of Alternate Nostril with long retentions, followed by either Even Count or meditation. Typically when I practice, I begin to become very aware of energy in-between my eyebrows as I sit upright and breathe. Yesterday however, I became aware of energy, yes, but that energy was very tired. After finishing the practice, instead of continuing on with my day, I laid down and slept for 45 minutes. The moral of the story is if you are tired it means you need to sleep! If you fall asleep in Shavasana, good! If you do pranayama and want to sleep, go for it. Ideally, we will lead a balanced life and we will get the rest we need. But in times when that’s not the case, we should take rest when we can. Yoga classes are filled with students of different skill levels. The majority of students are somewhere in the middle: familiar with the practices, having attended dozens or hundreds of classes, neither beginning nor advanced. Some are new, never having done yoga before, and a few are more advanced, having practiced for long enough to move past beginning techniques. As teachers, how do we navigate this diversity?

BEGINNING AND ALL-LEVELS CLASSES One of the solutions that the yoga community has developed is "Beginning Class" or "All-Levels Class." These classes are attractive to newcomers since the practices aren't too difficult, and tentative new students won't be distracted or discouraged by confident, flexible yogis on the mat next door. A beginning class is targeted toward beginners. "All-levels" is a descriptor that basically means "beginning," but it tries to avoid alienating more experienced yogis the way that a term like "beginning" might. The obvious complements to "Beginning" class are "Intermediate" and "Advanced" classes. But there aren't nearly as many intermediate or advanced students, so these classes are unsustainable to a yoga studio. Non-beginning classes generally get limited to once or twice per week or dropped altogether, while beginning classes fill the rest of the schedule. So it is difficult for intermediate and advanced yogis to find classes or spaces to practice at their level. What we end up with is more advanced students in "beginning" classes. It is the teacher's responsibility to direct the students in his or her class, whoever those students may be. A teacher needs to be able to guide a beginning student in appropriate beginning practices, and also guide an advanced student in appropriate advanced practices. This requires some knowledge and skill from the teacher, who needs familiarity with beginning postures, modifications and injuries as well as intermediate and advanced postures and variations. Too often, teachers hold back their advanced students, demanding that they do beginning postures that will not benefit them, or worse, encouraging them to do beginning postures but work harder. This is the most common way to injury. THEIR OWN PRACTICE We often hear yogis make the case that beginning students should embrace "their own practice," meaning that they shouldn't be ashamed if they struggle or look silly. This helps the student trust the process. But the same is true for the advanced student who needs to embrace "their own practice." Too many advanced yogis hold back their practice for the sake of someone else in the room. Ideally, a yoga teacher can direct students of all levels at once. The beginner gets simple instruction while the experienced practitioner gets more detail and depth. All parties should respect their own place and the place of their peers. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed