|

We recently had the pleasure of chatting with Henry Winslow for a new episode of his podcast, Dharma Talk. The episode is out now! You can listen to it here.

About the podcast: Yoga student and teacher, Henry Winslow, interviews inspirational yogis about their path and purpose in this life, and how their yoga practice has shaped it. Tune in each week for powerful stories of self-discovery, resistance, and triumph, and get inspired to live your dharma. Enjoy the podcast!

0 Comments

As the summer settles in, our teaching schedule lightens up. Ida and I don't travel as much or teach as many workshops during the warm months of the year. Inevitably this time away from teaching leads me to explore new areas of study and curiosity.

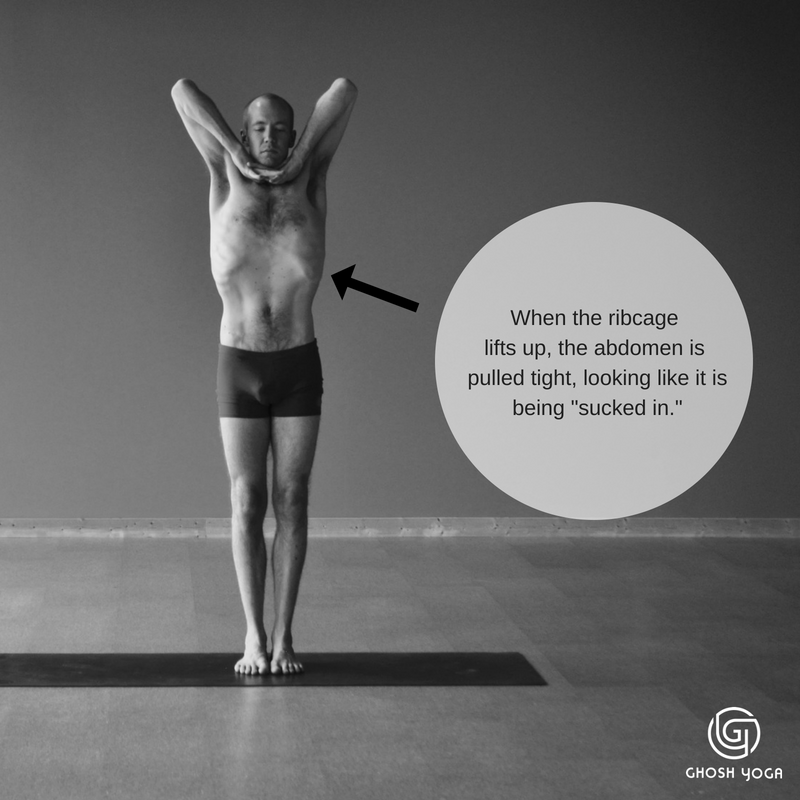

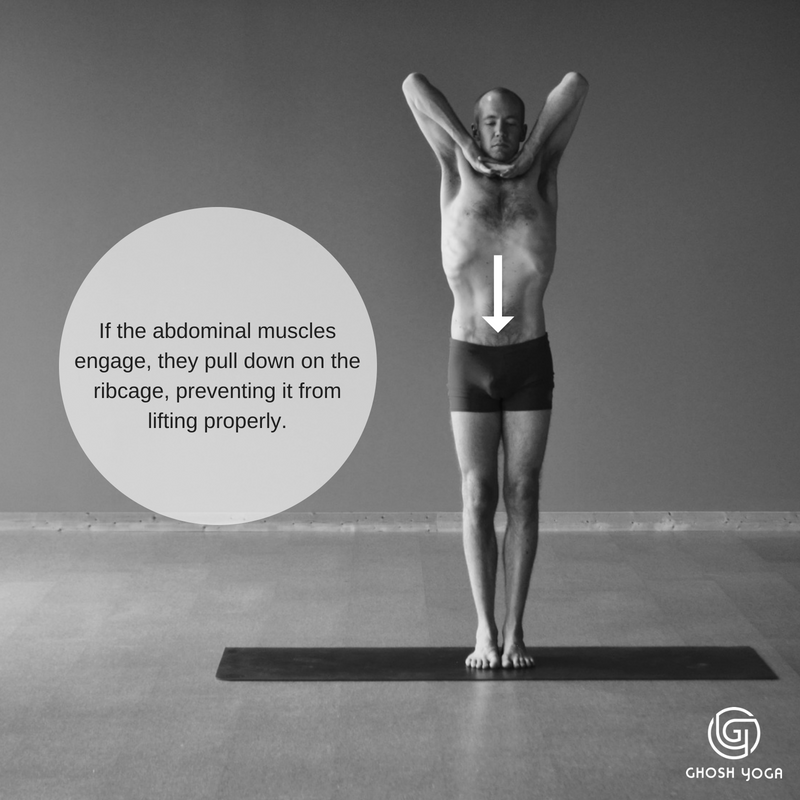

During the fall, winter and spring our schedule can be overwhelming and it is difficult to embrace new ideas. I may have an interesting conversation, learn about a new book or get a mind-boggling question that sparks my spirit of inquiry. But due to the requirements of travel and teaching those inquiries get put on hold until a later date. The procrastination and patience are important as we focus on the tasks at hand, but they can be frustrating too. Now, with the summer, the time has arrived to explore. The questions arise in me again and again: How can I be a good yogi and also a good person? Where is the balance between learning, knowing and teaching? How can I take responsibility for myself, my communities and environment while still staying humble? These are the questions that agitate me on a daily basis. I welcome any of your thoughts or insights. One of the main ways that we breathe is with our chest. The muscles between the ribs cause the ribcage to expand and lift up, drawing air into the lungs. This causes the abdominal muscles to become long as they are pulled by the upward motion of the ribs. The abdominal muscles must be relaxed for the ribs to lift fully.

When we recognize violence and suffering in the world, often our first response is, "How can I help?" What can I do to reduce the violence, to reduce the suffering?

It is easy to say that the world needs to change, or to try to affect change in the world. The problem with this attitude, from a yogic perspective, is that it externalizes. It has us imposing our will upon the world, usually at the expense of a clear view of ourselves. It is generally our most ingrained and obvious views that we seek to export to others. In the Yogasutras it is explained that, "When non-violence (ahimsa) is firmly established, hostility vanishes in the yogi's presence." (2.35) Only when we are peaceful ourselves can we affect peaceful change in the world. As one of our teachers said, "It is impossible to give what you don't have." If we are not peaceful, how can we give peace? It is as futile an effort as if we had no food but tried to give food to others. First we must have something before we can offer it. So, from the yogic view, the best way to reduce someone else's suffering is to eliminate our own. The best way to bring peace is to become firmly established in peace ourselves. Each of us is capable of remarkable progress in yoga. But that progress requires commitment and the recognition that there is more than one element to a well-rounded practice. There are four parts of a yoga practice, and when they are all incorporated, our progress is swift.

1. STUDIO PRACTICE This is the most common element of yoga practice, especially in the modern West. We go to our local yoga studio to do class, led by a teacher. These classes have the benefit of being scheduled, so we carve out time from our day to attend. Regular attendance leads to familiarity and hopefully expertise. The main drawback of studio classes is that they are geared toward the group and not the individual. The practices are generally "good for everybody," which often means they are not optimized for the progress of each unique student. There is great benefit to be wrung from Studio Practice, but it is important to complement it with Home Practice. 2. HOME PRACTICE The benefits and drawbacks of Home Practice are exactly opposite of Studio Practice. The main benefit is that it fits our skill level and trajectory perfectly. We can include practices that are challenging enough to enable progress; we can take time and repetition to build new skills. A Home Practice is vital for the progressing yogi. It will always be changing, because we are always changing. The main challenge of Home Practice is that it requires tremendous internal motivation from us, as opposed to a Studio Practice in which the teacher assumes responsibility for the student in motivation, choice and length of practices. At home, we have to carve out our own time; we have to ignore the dinging phone; we have to stay focused and alert all by ourselves. Great aids to this end are videos, books and pre-determining what our practice for the day will entail. 3. STUDY This, along with Home Practice, is where exceptional yogis are made. We go beyond the ordinary physical- and fitness-based approach and begin to explore its larger and deeper meaning. Study includes a vast array of subjects---and we can start with what interests us---from anatomy and psychology to history, philosophy and spirituality. The good news is that we really can study what compels us, as it will lead us to greater knowledge, understanding and curiosity. The challenge is simply finding time, plagued as we are by busy schedules and abundant sources of distraction. 4. INTENSIVE STUDY/PRACTICE WITH MASTERS In all walks of life, our habits blind us and we can lose track of the forest for the trees. In order to see ourselves clearly and keep from developing detrimental patterns, it is important to step outside of our daily routines once in a while. In yoga, this means finding yogis who have committed their lives to its practice and teaching. They have generally gone far and deep into the practices, and we benefit greatly from being in their presence and receiving their instruction. Their expertise is compounded by their fresh perspective---since they don't watch us practice everyday---and they will often see our weaknesses and potential immediately. The main drawback of studying with masters is that it takes great commitment of time and usually money. We may have to travel to another city and dedicate an entire weekend, week or month to their program. In our experience, it is usually worthwhile, but it doesn't make the decision any easier! We begin at the beginning. That much is obvious.

As we practice, we gain proficiency; we get good at whatever we are drilling. Soon enough, it becomes time to move on and up to the next level. Almost all disciplines take this process for granted. If you study music, you start with the Level 1 book and move through Level 2 up as high as you can, through maybe 6 to 10 levels. And that is all before you even arrive at the University level that plays the standard "repertoire" that makes up most concerts. Even school subjects progress through levels, building on one another to create complex and deep understanding. Arithmetic is layered with geometry, algebra and calculus to give the student a high level of competency in maths. Sadly, this structure rarely exists in yoga, especially in the West. The studio culture that has built up---where we attend a group yoga class in the morning or after work---contains almost exclusively "all-levels" classes, which means that they aren't particularly suited for beginners or experienced practitioners. Since we all begin at the beginning, we should do the simplest introductory practices. We are in Yoga First Grade, learning the yogic equivalent of counting and the alphabet. This includes things like touching our toes, awareness of the breath and perhaps even linking our breath with movement. Before too long we graduate to Yoga Second Grade, where we build upon the skills we have learned. This continues indefinitely as the practices become more and more complex. This may seem obvious, but it is quite common in the yoga world for beginners and experienced practitioners to do the same practices, the equivalent of having everyone in the room practice algebra even though some don't know how to add while others are astrophysicists. Who is being served? Practice must begin simply and it must evolve. It must grow and increase in complexity. As teachers, we must embrace and enable these qualities and capabilities in our students. Whenever we teach yoga, it is mostly done with words. We describe the actions, body movements, breathing, areas of concentration and purpose to our students. Sometimes there are moments of demonstration, discussion, contemplation and quiet practice, but for the most part yoga teaching is done by speaking. This makes our words important. What are we saying? And for what purpose?

OLD WORDS There is value in repeating the words of our teachers. It can root us in tradition, since our teachers often learned the same words from their teachers. It can also bring us closer to our own past experiences of practice, since we heard our teachers use the words while we were discovering. Now those same words can tether us to our own practice even as we guide others. Sometimes the words of our teachers are simply great, and try as we might, we can not invent a more effective way to describe a concept or action. In these cases, repeating our teachers is a wise choice. But there is also danger in repeating someone else's words, even when they come from a knowledgable, respectable source. The greatest risk is that we will instruct what we do not understand ourselves. When we already have instructions ready to disperse, there is little motivation to plumb the depths of practice and then teach from our own knowledge. We may end up teaching things far beyond our own ability and understanding, and this is bad for everyone--us, the students and the knowledge that we are claiming to perpetuate. Another danger is that speaking someone else's words can disconnect us from our own knowledge and experience. It is easy to switch to autopilot when we have the words ready beforehand. We can disconnect from our own practice as well as the needs of the students in front of us, simply repeating prepared statements that may or may not apply to the current moment. NEW WORDS Sometimes we invent our own instructions to guide our students. This has the advantage of being absolutely real and true; we aren't instructing what we've heard or read but what we've practiced and experienced. Almost always these words are clear, evocative and precise. When we speak with our own words, we are forced to connect our brains (and mouths) to our own knowledge, and this brings unity to both our teaching and practice. Disparate parts become unified. Also, this forces us to teach what we know. When we use our own words, there is no possible way to instruct something beyond our own understanding. The greatest danger to teaching in the moment with our own words is that we can lose humility and become caught up in our own story. We get intoxicated with the sound of our own voice, convinced that our experience is worth trumpeting, that our instructions are worth following. This perspective is ruinous to the yogi, as the ego can grow and drown out all yogic knowledge and humility. IN CONCLUSION There are pros and cons to repeating traditional words, old phrases and the words of our teachers. The same is true for inventing our own instructions directly from personal experience. Above all, we must be aware of what we say and why, and also what impact the words have on our students and us. Calcutta Yoga is a new book about the history of yoga in Calcutta, covering 4 generations of the Ghosh and Bose families. Below is an excerpt from early in the book, about Buddha Bose's birth in 1912. It begins with his parents, Rajah and Emily. Learn more and purchase the book here. Chapter 3 |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed