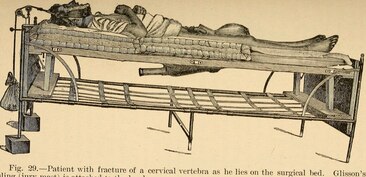

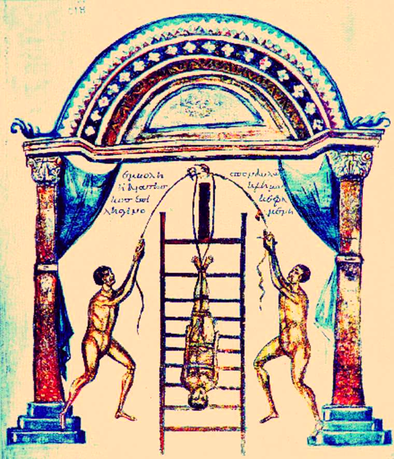

From "Saunders Medical Hand-Atlases - Fractures and Disclocations", 1902 From "Saunders Medical Hand-Atlases - Fractures and Disclocations", 1902 Traction the spine! Natural human traction! We hear these phrases in yoga classes. But what is traction? Do postures really provide traction?! The quick answer: No, yoga postures do not traction the spine. Here is why. CONTEXT Traction Therapy is defined as a technique that separates the spinal vertebrae by mechanical force. Interestingly, there is evidence of the use of traction dating back 4,000 years. Historical records show that even Hippocrates invented an apparatus to traction the spine around the 4th century BCE. TWENTIETH CENTURY The early twentieth century was the era when asana flourished and health of the body was of primary importance to the evolving practice of yoga. Not coincidentally, this was also an era when low back pain was commonly being treated using traction devices. Given this overlap, the language of traction in yoga makes sense as yoga swallowed up a lot of health-based language of the era. (Other examples include the focus on the spine in general, deep breathing, circulation, focusing on the organs and glands, to name a few.) Furthermore, it makes sense that since traction was popular in the early twentieth century particularly within British medicine, that it would influence modern yoga as it developed in Colonial India. Today traction is most often used as a method to reset a dislocated joint. Significant external force is applied to put the body back together from an injury. It is less common that traction is used today as a therapy.  It is commonly said that traction occurs in Balancing Stick, but this is not physically possible due to the lack of apparatus. It is commonly said that traction occurs in Balancing Stick, but this is not physically possible due to the lack of apparatus. TRACTION IN YOGA As we saw from the definition above, traction requires external force. Mechanical force is applied to the body. This force can come from weights or pulleys. So, can we use traction in a bodyweight movement? The answer is no. We cannot traction in yoga, because there is no external force. Often it is said that reaching the arms tractions the spine. But this is not the case. The shoulders actually get there stability from the spine and do not move the spine. Any reaching with the arms is called shoulder elevation, essentially engagement of the upper trapezius, rhomboids and levator scapulae. Even if two people pull on the arms and lifted leg in Balancing Stick, this will still not traction the spine. This is because the joints that would be receiving the force of the pull are the wrists, elbows, shoulders and the ankles, knees and hips. These are not the spine. SUMMARY While the language of traction makes sense for the evolution of yoga, actual traction is not possible in a bodyweight movement. (The small caveat to this the use of gravity in very specific circumstances.) Traction requires external force. However in postures where traction is taught, like Balancing Stick for example, the spine cannot traction because there is nothing pulling on it. Any movement of the body which makes the spine look like it is getting longer, is not actually the vertebrae separating. There is not a scenario in which "natural human traction" without external force is possible. Even Hippocrates needed a contraption to traction the spine. Source: Ralph E. Gay, Jeffrey S. Brault, CHAPTER 15 - Traction Therapy, Editor(s): Simon Dagenais, Scott Haldeman, Evidence-Based Management of Low Back Pain, Mosby, 2012, Pages 205-215, (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323072939000155)

0 Comments

Yoga is constantly being defined. Nearly everyone in the yoga world seems willing and eager to tell you what yoga means. This is often paired with judgement about all the things yoga is not. The person defining it usually assumes that they are correct and that anyone who doesn't agree with them is incorrect. So really, what is the definition of yoga? There is no singular definition of yoga. Anyone who tells you otherwise is actually suggesting what yoga means to them, not what yoga means. Yoga is a vast concept, which has moved across time, place, culture and context. As a practice, yoga can be material or transcendent, literal or figurative. It can be religious or secular. It can be a practice to cultivate the body or a practice to destroy it. For the Classical Yogis, yoga is the goal. For the Jains, yoga is a problem. Yoga is exercise for some practitioners today. For others, it is offensive that anyone considers it to be exercise. Historians on yoga explore how the meaning of yoga has always been in flux. It has always evolved and been defined then redefined. Foxen and Kuberry write "the fact of the matter is that ‘yoga’ is a very basic and generic type of word” and “yoga practices (the entire spectrum of them) have continuously changed and evolved in tandem with the culture around them” (Foxen & Kuberry 2021, p. 5). Do you think about the definition of yoga? Do you feel strongly that it means a specific thing? We will all certainly have personal opinions on yoga. But we should not mistake our views on what yoga is as the one definition of yoga. Anyone who defines yoga is not defining yoga. They are defining what yoga means to them. Source:

Foxen & Kuberry, 2021. Is This Yoga?: Concepts, Histories and Complexities of Modern Practice. Routledge. In this blog series, we will explore the difficult tendencies of the mind as taught and described by various traditions of meditation. Buddhism suggests that there is suffering, and suffering arises from desire. This desire is referred to as thirst or craving. If we all have desire, and therefore suffering, where does it come from?

In Buddhism, desire comes from greed. We can want any number of things. Cravings are endless. There might be sensory desires like foods or drinks, experiential cravings like entertainment or travel, or egoic desires like fame or power. These can be linked to each other-- a meal that makes us feel like a king or queen, for example. In this case, there is sensory craving alongside a sense of power or stature. The teaching on greed and desire suggests that it does not matter what the object of craving is, it is craving itself which is the root of suffering. We have to eliminate desire to eliminate suffering. We cannot simply eliminate the objects of our desire. Let's look at some textual passages. In the Buddha's Final Nibbana, it states: When one gives, merit increases; when one is in control of oneself, hostility is not stored up; The skillful man gives up what is bad; with the destruction of greed, hatred and delusion he is at peace.* If greed is the problem, instead one should give. This gets at the idea of cultivating the opposite, which is also found in the Yoga Sutras: When one is plagued by ideas that prevent the moral principles and observances, one can counter them by cultivating the opposite. Cultivating the opposite is realizing that perverse ideas, such as the idea of violence, result in endless suffering and ignorance--whether the ideas are acted out, instigated, or sanctioned, whether motivated by greed, anger, or delusion, whether mild, moderate, or extreme.** The idea is to cultivate the opposite of greed or desire. If we do so, we will realize that greed only results in suffering. What are some ways we can cultivate the opposite of greed and desire? Sources: * Mahaparinibbana Sutta, D II 72-168 in Gethin, R. 2008. Sayings of the Buddha. Oxford World's Classics: Oxford, pp. 78 ** Yoga Sutras 2.33-34 in Stoler Miller, B. 1995. Yoga Discipline of Freedom. Bantham Books: New York Gethin, R. 1998. The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press: Oxford In this blog series, we will explore the difficult tendencies of the mind as taught and described by various traditions of meditation. The Buddhist meditative tradition teaches that there are five hinderances of the mind. These are mental factors or states that exist and arise in the mind. These qualities prevent the practitioner from making progress in meditation.

The five hinderances, as taught in Establishing Mindfulness (Satipatthana Sutta)* are: 1) sensory desire, 2) hostility or ill-will, 3) dullness or lethargy, 4) agitation or worry, 5) doubt. It is the practice of mindfulness that allows us to recognize these qualities in the mind. The practitioner recognizes when they are present and when they are not present. Through practice, if and when these qualities are abandoned, the practitioner knows they will not arise in the mind again. The practice of mindfulness consists of sitting in contemplation and establishing mindfulness. There are four phases: mindfulness of the body, feelings, mind and qualities. Within the explanation of the last section, qualities, is the explanation of the five hinderances. It is taught that if one is able to live in recognition that there are these qualities, one can be aware as they come and go without holding onto them. Source: * Satipatthana Sutta, M I 60 - Sayings of the Buddha, Rupert Gethin, pp. 147-148. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed