|

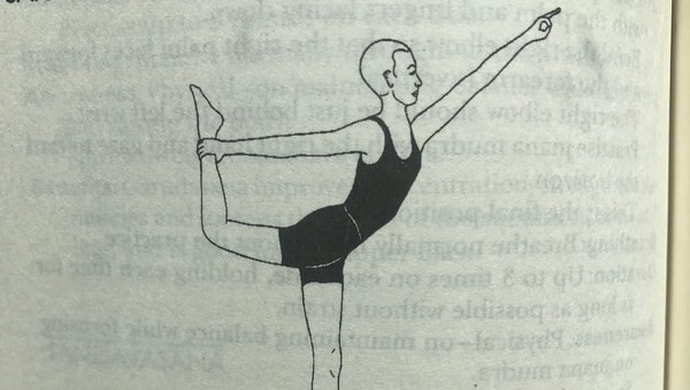

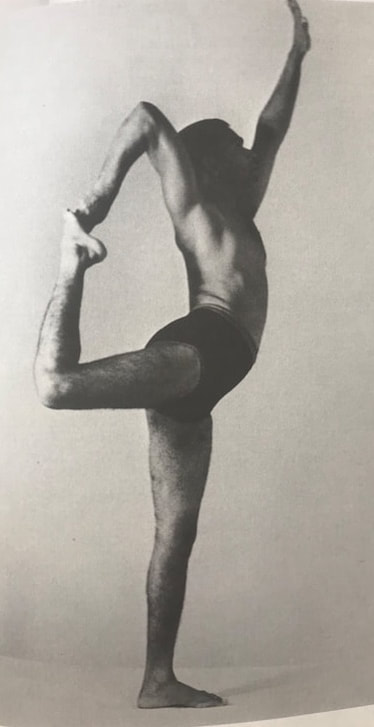

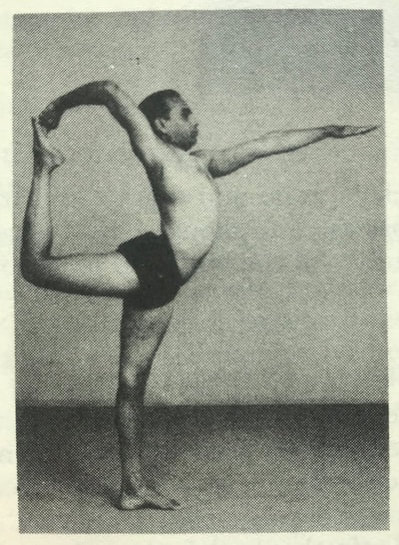

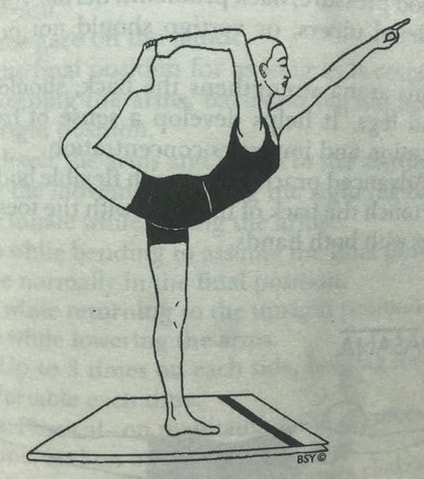

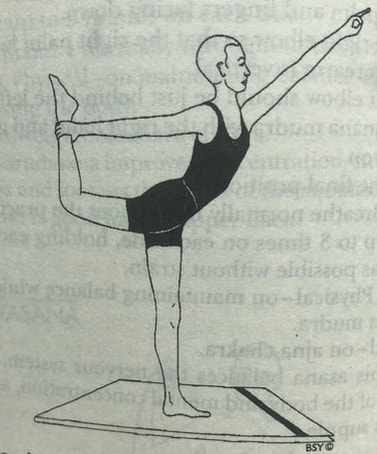

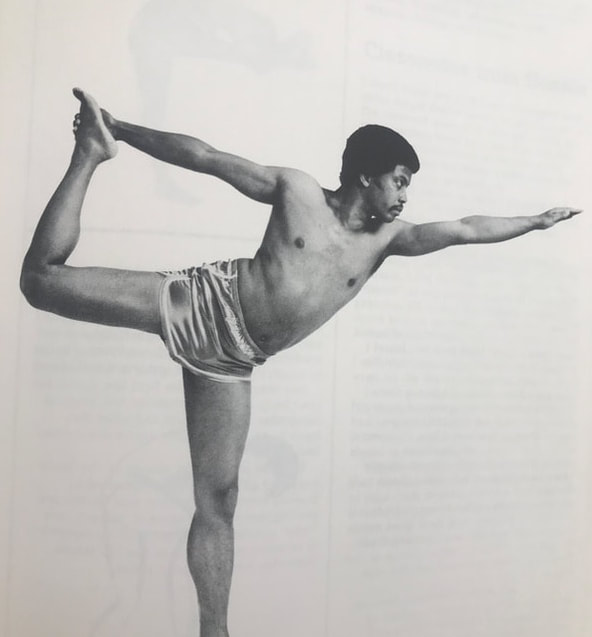

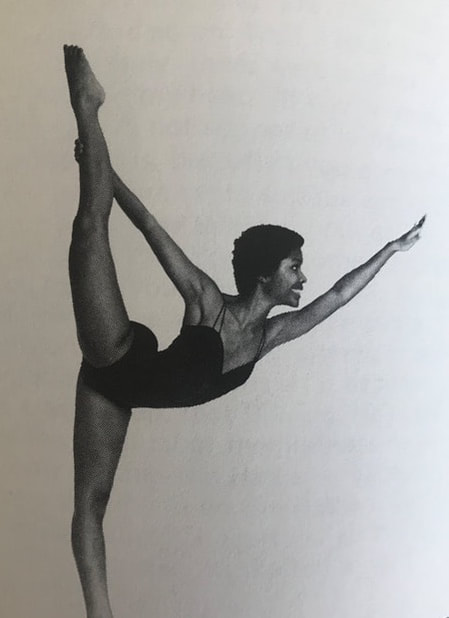

A couple years ago we did a comparison of all the postures in significant publications from the Ghosh yoga lineage. There were a couple of surprises in that search. One of the most significant was the complete absence of Standing Bow Pulling posture in any of the texts. Why was this posture missing? Where and when did it come from? And how did it become so central to Bikram Choudhury's system of 26 postures that he developed in the 1970s? Upon further research, it seems that Standing Bow Pulling posture is a descendant of a more difficult position, Lord of the Dance. But even Lord of the Dance is a recent addition to the yoga canon, appearing only in the 1950s or '60s. It seems that Lord of the Dance popped up in south India, perhaps coming from Indian dance, contortion and gymnastics, and quickly spread. Its transition toward Standing Bow Pulling didn't come until late in the 1960s. Let's start at the beginning... Obvious as it may be to state, Standing Bow Pulling and its predecessor Lord of the Dance posture (Natarajasana) are nowhere to be found in the pre-modern texts of yoga. As physical postures were becoming more prominent throughout the development of hathayoga, they were largely seated or lying positions. Almost no postures in hathayoga are done standing. Even as we entered the 20th century and the fathers (sadly we don't know of many mothers) of modern yoga revolutionized the discipline, the acrobatics and deep stretching that we recognize today were still scarce. Early pioneers like Yogendra, Kuvalayananda, Krishnamacharya, Shivananda of Rishikesh, Bishnu Ghosh and Buddha Bose greatly expanded the number of positions in "yoga" through the 1920s, '30s and '40s, but still there was nothing resembling Standing Bow Pulling. At that point, yoga was largely adopting the practices of calisthenics and marrying the breath with relatively simple movements of the body.

IN CONCLUSION This all makes Choudhury's Standing Bow Pulling posture fascinating and very new. It seems to be based on a modification or preparation for Lord of the Dance, which itself is a recent addition to the yoga asana canon. And further, this variation continues to be deepened and elaborated until it has become essentially a new posture in its own right. 1. Goldberg, Elliott. The Path of Modern Yoga. p395

2. Swami Satyananda Saraswati. Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. 2012 (1969).

4 Comments

As yoga teachers, the words we use are of the utmost importance. This is how we transfer information to our students. People come to a yoga posture class to gain a better understanding of their practice, make progress and generally feel better. We want to help them achieve these goals.

With this in mind, there are three categories of cues we can use. Let's look at the different types of cues and how we can incorporate them. TYPE 1: Cues that get the right result and teach people how their body works. This type of cue gets people to move their body in the direction of the pose, while putting their mind right where the action happens. To better understand this, we'll use the example of a backward bend of the spine. In all backward bends of the spine, we want the back muscles (erector spinae) to engage. Knowing this, a cue such as "engage your back muscles to bend your spine" teaches what to do and how to do it. We should use this type of instruction as much as possible. The sticking point becomes if people do not understand how to access the muscles we are asking them to use. This brings us to the second type of cue. TYPE 2: Cues that get the right result but do not teach people how their body works. These types of instructions get people to move in the shape of the posture, but don't put their mind in the right place. Let's stick with the backward bend example. Often we will say "lift your chest up." This cue almost always gets the right result in the body. However, the action that makes the chest "lift up" is nothing more than the back muscles engaging! So while this instruction teaches our students what to do, it does not teach them how. Over time this can lead to students that are very confused in their postures, and have their mind focused on areas of the body that will not help them do what they are trying to do. TYPE 3: Cues that do neither. Cues that do not teach what to do or how to do it, are usually born from the desire of the teacher to be creative or interesting. While it's a valid temptation, we should try not to fall for it. Our desires should never get in the way of our student's progress. Simple and clear instruction is the best road forward. The physical practice is hard enough as it is. All instructions are not created equally. If our goal is to help people as much as possible, we should focus on the cues that will do just that. Teach them what to do and how to do it. So many of us practice physical postures on a regular basis. In doing this, it's easy to lose sight of what these postures really are, and why we practice them in the first place.

A posture is a set of muscular engagements and relaxations. Figuring out what is happening in each position and using our muscles accordingly, is the goal of a physical practice. Once we find the correct musculature in a pose, we adjust our breathing, focus our gaze and enter stillness. Each posture is different, hence the different shapes. Where we get into trouble is beginning to think, consciously or not, that simply getting our body into the shape of a posture is the goal. This becomes a problem when we look like we are doing a posture, but we don't have correct control over the musculature of the pose. This often happens in a forehead to knee poses for example. We become focused on touching our forehead to our knee rather than being aware of the mechanism that rounds our spine and makes this happen in the first place. (The abs!) Or we become focused on pulling with our arms in Hands to Feet, thinking we will get further in the pose. (Pull with the arms doesn't teach our body to stretch properly, and often leads to injury over time.) The Ghosh style of physical practice is built upon principles of muscle control. As Bishnu Ghosh himself explained, "Controlling of any muscle is nothing but to contract and relax the muscles without any movement of the limbs or contraction of any other muscle.” In posture practice, we should seek to develop our muscle control, remembering that the shape isn't worth making if our bodies aren't working correctly. Five years ago Ida and I set foot in Kolkata for the first time. I was certain it would be our only visit, since the circumstances were so utterly odd and couldn't possibly be replicated. We were searching for the roots of Buddha Bose's manuscript which had been written in 1938 but never published. The reason for its disappearance was unclear, and that's what we were in Kolkata hoping to understand. Ida and I were the second and third wheels of Jerome Armstrong, who had tracked down the manuscript through some impressive sleuthing. He didn't want to make a trip to the other side of the world alone and so enlisted our company. How could we say no? The three of us arrived in Kolkata in the middle of the night. Our flight landed at 2 a.m. and we stepped into the hot, humid Indian darkness. The city never quiets down, and the streets were filled with drivers leaning against their yellow cabs and passing the time in conversation. We found a proprietor who ensured us he could take us where we were going, and after Jerome hilariously tried to get into the driver's seat--located on the right side of the car in India--we were off. Even though it was approaching 4am, we insisted on locating Ghosh's College of Physical Education before proceeding to the hotel. None of us had been to Kolkata before, and our ignorance was made worse by the blackness and the fact that our GPS didn't work in a foreign country. We were confined to guesswork and imperfect commands to the driver. After a few confounded circles we found the gate, and so our Kolkata experience commenced with a predawn photo of our trio outside the College, while those who weren't sleeping looked on with disbelief and mild annoyance. We stayed at the Hotel Neeranand, which far exceeded my expectations with its delicious breakfast--I had feared that I would be unable to eat much food simply due to its unfamiliarity--occasionally functioning WiFi and lukewarm water. To our great relief, the room had a Western style toilet, though it had no seat. It wasn't until the last day of our visit that we realized it was a mistake. Directly prior to our departure, a new paper-wrapped toilet seat appeared in our bathroom, with apologies for its tardiness. I had resigned myself to its absence, grateful for anything that flushed. The first day began without hesitation, as we met Buddha Bose's grandson, Pavitra, and ex-daughter-in-law, Chitralekha, for breakfast at the hotel. Since Bose had married Bishnu Ghosh's daughter, Pavitra is also the great-grandson of Ghosh and Yogananda. He looks it, with a round face and piercing black eyes. They sat down across the table from us with palpable distrust. Who were these Westerners who dared to poke their noses into Bose, Kolkata and yoga? Fair enough. But Pavitra and his mother had come to meet us nonetheless, perhaps driven by curiosity or amusement. As we sat together on the roof of the hotel in the bright morning sun, they flipped through the photocopied manuscript and became more and more engrossed as they realized its authenticity and were reminded of their love for Bose and the methods of yoga. We, the imposing Westerners, quickly faded into non-existence. Next stop: the National Library, a goliath of storage and a relic of pre-digital organization. The building is huge, with an entryway that only hints at the vast treasures hidden in the back rooms and basements. It reeks of mildew and age, of written human history that is disintegrating one monsoon at a time. On the quest for Buddha Bose's story, Jerome had stumbled upon a later publication that Bose wrote about pilgrimages into the Himalayas, named Holy Kailas after the sacred mountain. Pavitra came with us. He had never seen nor heard of this book by his grandfather. It took a couple hours of filling out forms and waiting, dazed as we were with exhaustion from travel, jet-lag and the excitement of a new world, but eventually the library staff called our number and delivered Holy Kailas. We returned to Ghosh's College in the daytime when it was open. Muktamala, Ghosh's granddaughter who runs the school, agreed to teach the three of us a class if we came back when the school was closed on Sunday. Cost for the class would be about $20 per person, which is outrageously expensive for Kolkata. But we would pay that for a class in the states, and how often would we get the opportunity to take a semi-private lesson with BC Ghosh's granddaughter? We agreed. The hour-long class she led us through included lots of therapeutic exercises and a handful of postures, plus a little meditation at the end. Little did we know at the time that a yoga "class" was unusual at Ghosh's College. Most yoga there was done via individual prescription as opposed to led group class. Afterward, Jerome asked Muktamala if she would teach Westerners how to do the exercises and prescriptions. Without hesitation, she agreed. The primary purpose of our trip was a meeting with Bose's daugther, Rooma, who runs the school that he started in the 1970s, the Yoga Cure Institute. We taxied to newer neighborhoods in southern Kolkata where the school is located and were invited into the office for about an hour with Rooma and her husband. They insisted that we did not record the meeting or even take notes, admonishing us that asking questions of the teacher was disrespectful. The student simply sits quietly and absorbs what the elder deems important to impart on any given day, Rooma's husband said. It seemed that the very fact of our coming here was offensive in its audacious curiosity. Our discussion was polite and wide-ranging. Rooma told us that they knew of the manuscript, had an original copy, and that it was never "lost." That Bose had chosen not to publish it because of errors. They did not show us their copy or offer any evidence of their claims. She told us a few stories about performing stunts in the old days, like lying across a sword while a brick was broken on her back. And she pointed us to an invaluable new character of whom we had never heard: Dr. Gouri Shankar Mukerji, mentioning offhand that he wrote an exhaustive book in German. I was wholly unprepared for the power of 11.5 hour jet-lag, almost completely opposite of what my body expected as far as sleeping and waking. Each day was ghostly, bright and hot while my brain tried to dream. The nights were vivid and alert, only adding to the other-worldly impression of Kolkata.

That trip would not be our last to India. Since then, Ida has gone to Kolkata at least twice every year to help at the College and to do research. I have gone back about once per year. My original assumption, that this excursion would be my only one, turned out to be absurdly false. India and Kolkata are endlessly fascinating and engrossing. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed