|

The last blog of this series tackles the most technical and muscular relationship of effort and ease: the relationship between contraction and relaxation.

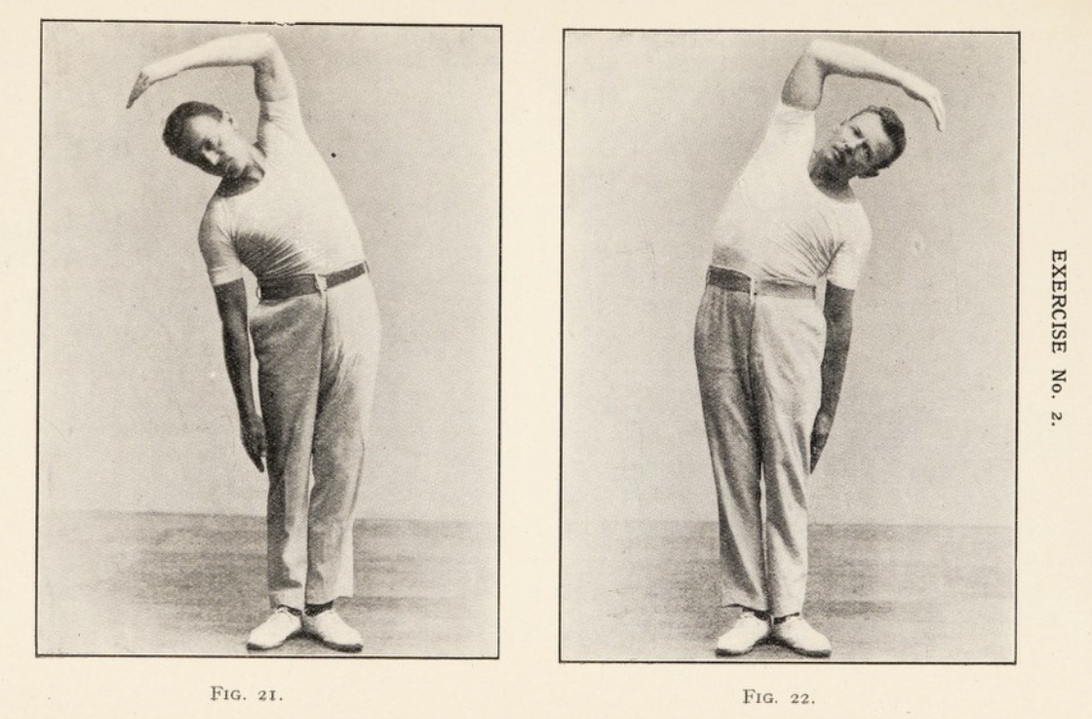

We started this series with the first type of effort and ease which is the combination of shavasana and asana. Then we moved to the second which is pose and counter-pose. Now we close with reciprocal inhibition. Reciprocal inhibition describes the muscular relaxation of one side of a joint in order to accommodate muscular contraction on the opposite side. This means that when the biceps contract to bend the elbow, the triceps know to relax. Or when hamstrings contract to bend the knee, the quadriceps know to relax. In asana, this means that something is relaxing even if we notice effort. It also means that relaxation of a muscle in a posture is the result of contraction. Let's take the example of the spine in Half Moon Sidebend, pictured above. When bending to the right in this posture, the left side of the body gets longer. This is relaxation or stretching. However, this stretch is only the result of engagement on the other side. So when bending to the right, the right side contracts and shortens. This is engagement. We are not trying to relax everything, but we are also not trying to contract everything. We need the opposites to be in conversation with one another: one side contracts and its opposite relaxes. This will happen somewhat naturally due to reciprocal inhibition. However, if we understand this concept we can be more precise in practice. We should always focus on contraction of the correct muscles in each posture, knowing that relaxation will result from correct engagement. This concept, reciprocal inhibition, represents the third way in which we cultivate effort and ease. Within each posture, even when they feel quite challenging, there is still relaxation. Where there is effort, there is always ease.

0 Comments

Continuing the conversation about alignment from the last episode, the discussion veers into 'prana' and 'virtue.' How does the body affect the flow of prana? For that matter, what is prana? And how does our physical alignment affect or symbolize our moral nature? Scott and Ida discuss these questions, along with abundant references and tangents.

Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts. In this blog, we'll explore the second type of effort and ease that is important in the Ghosh lineage: pose and counter-pose.

This is the belief that asanas should be practiced in pairs. With regard to the body, whatever was shortened in the first asana should be lengthened in the second. Or, whatever was contracted in the first, should be relaxed in the next. This is usually demonstrated with back and forward bends of the spine. A simple version of this is Camel & Rabbit, as pictured above. Since Camel pose engages the back and relaxes the front, we must follow it by Rabbit pose which does the opposite. By practicing asanas in pairs, we cultivate effort and ease through each pose and counter-pose combination. HISTORICAL CONTEXT This instruction is not presented clearly in the early writing from the Ghosh lineage. But by the time of Dr Gouri Shankar Mukerji in the 1960s it is. In 1963 he writes: "The sequence of exercises should be chosen in a way that body parts or muscles opposite to each other will always be stressed, thus after an exercise extending the spine follows one bending it (p. 7)". He explains this method in terms of the sequence one should practice while noting what is opposite in the body. CONCLUSIONS In the first blog of this series, we focused on shavasana as the ease that follows the effort of each posture. Here we bring attention to the fact that when we pair asanas together by pose and counter-pose, we cultivate a sense of effort and ease. What was exerting effort in the first pose, is relaxed in the next. This combination results in a balance of effort and ease. In the final blog of this series, we will focus on the third type of effort and ease. This is the combination of engagement and relaxation that happens in each posture.

Yoga World is back! After a two year (!) hiatus, we 're back with the concluding episodes of Season 3: All About Asana.

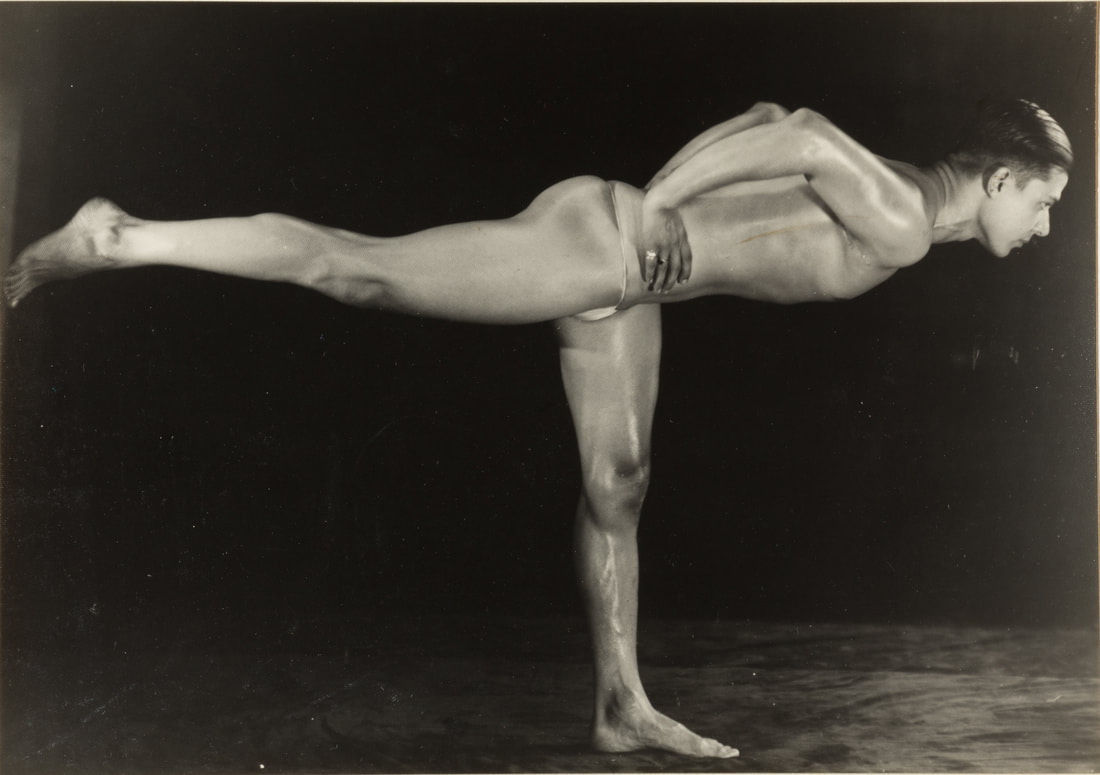

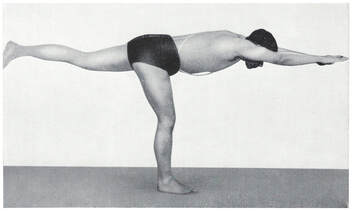

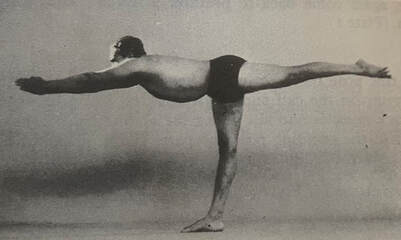

In this episode, we discuss the nature of "alignment" throughout the last hundred years. Did older texts talk about alignment? When did it become important, and how did that change the way we practice yoga? Is alignment a good idea? We cover early pioneers such as Krishnamacharya, Shivananda and Yogendra, as well as Iyengar and Jois, all the way into the modernity of Birch. This episode is the first of two about alignment, covering the first three "buckets" of what it means. Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.  Buddha Bose in Tuladandasana, in 84 Yoga Asanas, 1938 Buddha Bose in Tuladandasana, in 84 Yoga Asanas, 1938 Balancing Stick is a common posture in the Ghosh lineage. It is also in Bikram Yoga (26+2). It is essentially the same posture as what is known as Warrior 3, or Virabhadrasana 3, in Iyengar and flow styles of yoga. The purpose of the posture in the Ghosh lineage is to 1) cultivate balance, 2) strengthen the back of the body, particularly the back of the standing leg. BEFORE IYENGAR In 1938, Buddha Bose instructs to keep the hands on the hips and "bend forward raising the right leg backwards". In 1963, Dr Gouri Shankar Mukerji instructs to "balance on one leg and lift the other leg back without ending the knees (p. 119)." He says that the posture promotes balance of the body and that the muscles of the hip and back are exercised (p. 120).  Dr Gouri Shankar Mukerji in Tuladandasana, in 84 Yoga Asanas, 1963 Dr Gouri Shankar Mukerji in Tuladandasana, in 84 Yoga Asanas, 1963 IYENGAR'S INFLUENCE In 1966, Light On Yoga by Iyengar is published. The impact of this book on yoga is immense. In his instructions for Virabhadrasana 3 he writes about pulling and stretching. The instructions state, "Pull the back of the right thigh and stretch the arms and the left leg as if two persons are pulling you from either end (p. 74)." Nowhere was this language of pulling and stretching found in the Ghosh lineage instructions prior. However, after Iyengar, we do see it. AFTER IYENGAR In 1978, Bikram Choudhury writes in Bikram's Beginning Yoga Class, "The only way to keep your tummy and chest and left leg safe is to stretch your torso forward like crazy by lifting, ever lifting your arms and head, while you stretch more and backward with the pointed foot and ever more forward with the fingertips, all the while lifting at front and back (p. 65)."  BKS Iyengar in Virabhadrasana III, in Light on Yoga, 1966 BKS Iyengar in Virabhadrasana III, in Light on Yoga, 1966 This is a little wordy and indirect, but still introducing the idea of stretching while in the pose. However, by 2007 the instruction is nearly identical to Iyengar's. Choudhury writes in Bikram Yoga, "Imagine a tug of war: Someone is pulling your back foot toward the wall with all his might and someone else is pulling your outstretched hands as hard as she can in the opposite direction (p. 132)." CONCLUSIONS Iyengar's instructions have most certainly influenced how Balancing Stick is taught. We feel this is somewhat unfortunate for the following reason: the purpose of the posture is lost if we focus not on the standing leg and balance, but on the outstretched arms and back foot. (The concept of traction or stretching in opposite directions is also misleading, but that's for another blog....) Regardless, it's interesting to note the similarities in the postures and the evolution of the instructions. Bibliography:

84 Yoga Asanas by Buddha Bose 84 Yoga Asanas by Gouri Shankar Mukerji Light On Yoga by BKS Iyengar Bikram's Beginning Yoga Class by Bikram Choudhury & Bonnie Reynolds Bikram Yoga by Bikram Choudhury The Ghosh lineage of yoga is unique in the way it understands the relationship between effort and ease. There are three distinct ways, all of which are at play in asana practice.

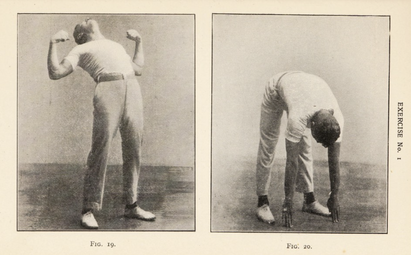

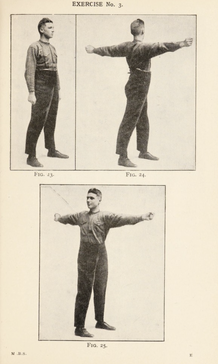

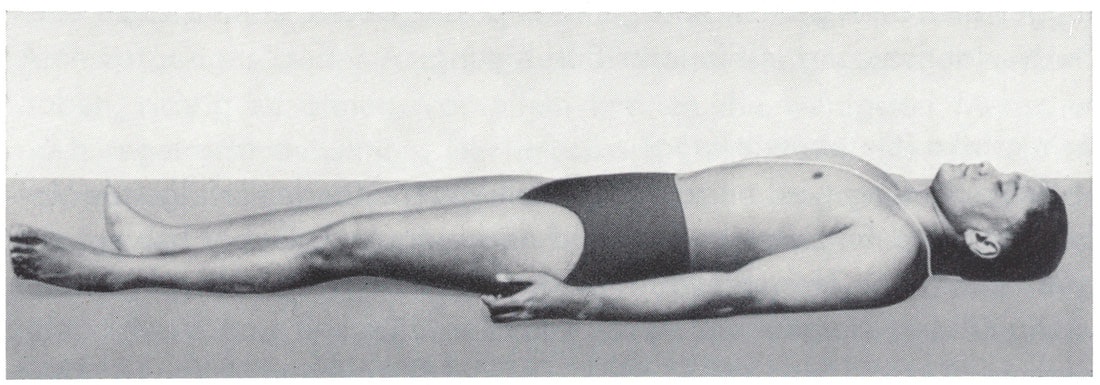

In this blog series we will describe each of the three, beginning with the first and most basic: posture & rest. SHAVASANA: A VERY BRIEF HISTORY Shavasana, called Corpse or Dead Man Pose, was named as an asana (posture) in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. Prior to that, it was a practice called laya yoga in which the practitioner tried to dissolve their material body. In the Ghosh lineage, rest is at the heart of asana practice. This is due to the influence of weightlifting, in which the exertion of force is followed by (sometimes a few) minutes of rest. As asana practice developed in the twentieth century, shavasana was emphasized in the practice of yoga, particularly in northern India and by weightlifters. INSTRUCTIONS FOR PRACTICE In the 1960s, Dr Gouri Shankar Mukerji not only writes about the importance of shavasana but says that it must be practiced after every other asana. He writes, "Any asana that you practice gives the full benefit when you end it with Shavasana (p. 12)." Taking it a step further, he explains: "The starting position for all exercises is a relaxation pose that is called Shavasana or Dead Man Pose. This posture is also resumed after each exercise and is to be considered an essential part of Yoga, because this system is based on an alternation between tension and relaxation (p. 5-6)". Not only is shavasana an important posture, but it represents a system of effort and ease that is foundational to the Ghosh lineage style of practice. In the next two blogs, we will examine the other two relationships of effort and ease: pose & counter-pose and muscular function.  JP Muller's Exercise No 1 in My Breathing System, 1914 JP Muller's Exercise No 1 in My Breathing System, 1914 For years, it has been known that Danish Lieutenant JP Muller's books were very influential on yoga as it developed in the twentieth century.* Muller wrote a handful of books on exercise, his most famous called My System. However, until now we had never realized the extent to which the warm-up series in Bikram Yoga (26+2) so closely follows Muller's exercises in My Breathing System. Muller's Deep Breathing The book My Breathing System was first published in 1914. In it, Muller teaches what he calls "Deep Breathing". Muller writes about the importance of learning to breathe correctly saying, "Of course everybody does breathe after a fashion, otherwise they would die. But few understand how to breathe, inhale and exhale, correctly." He writes about the "evils" of shallow breathing and that deep breathing must be taught. After explaining the concept of deep breathing and anatomical function, he instructs his "Five Minutes' Breathing System". You may recognize the movements!  JP Muller's Exercise No 3 in My Breathing System, 1914 JP Muller's Exercise No 3 in My Breathing System, 1914 Muller's Five Minute's Breathing System "Exercise 1: Full body breathing combined with backward and forward bending of body combined with bending and straightening of both arms simultaneously." "Exercise 2: One-side full breathing during sideways-bending of trunk, combined with alternative lifting over head and stretching downwards of arms." "Exercise 3: Full breathing during twisting of trunk to alternate sides, combined with arm-raising and lowering to the sides. "Exercise 4: Full breathing during arm-raising to front and lowering, combined with quick deep knee-bending, feet apart and without heel-raising." There are five more exercises in this system, but they are less notable here. One incorporates a common practice at the turn of the twentieth century: rubbing or tapping the body. The additional exercises are also alternative versions of the ones listed above. For example, side bending is repeated but with an emphasis on pushing the hips to the side and bending one knee. And notably, Exercise 4 (deep knee bending) is repeated but with a heel raise. This becomes like the second part of Chair pose in the 26+2.  JP Muller's Exercise No 4 in My Breathing System, 1914 JP Muller's Exercise No 4 in My Breathing System, 1914 Conclusion While there are many similarities between this and the 26+2, there are of course differences. The 26+2 series places the side bend of the spine before the back and forward bend and does not include a twist. What is interesting about this, is that a twist would benefit the Half Moon warm-up in the 26+2! It's the missing element in the spinal movements. Either way, it is quite stunning to see the bends of the spine followed in order by a position like Chair, with the arms held up and forward. It's also interesting to consider this in a book about deep breathing. Much more could be said about the actual instructions Muller gives and his ideas about the benefits and function of deep breathing. Perhaps we will tackle that in a future blog. For now, we hope you enjoy seeing these 100+ year old photos of what we have come to recognize as Half Moon and Chair. *See Singleton's book Yoga Body Bibliography:

Muller, JP. 1914. My Breathing System. London: Athletic Publications, Ltd. Singleton, M. 2010. Yoga Body. Oxford: Oxford University Press |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed