|

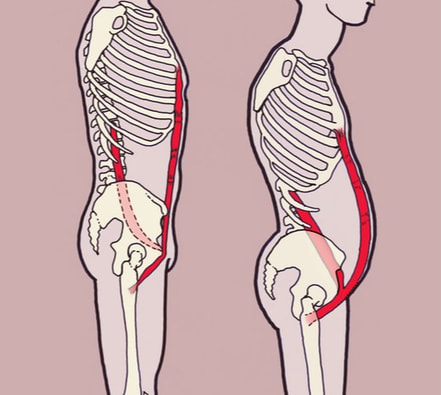

Most of us don't know where our psoas (pronounced so-az) muscle is. It is deep in the body, underneath our abs and guts, but it has a huge effect on the spine and hips. The psoas hugs the lower spine, the inside of the pelvis and crosses the hip. Its main function is to move the leg by flexing the hip, but the fact that it connects to the spine makes things a little more complicated. It is commonly ignored or misunderstood since it is not readily visible or easy to feel, but it is a vital muscle for our posture, our spinal and abdominal function, and our hip function.

In the picture above, the psoas and the rectus abdominis (6-pack) muscles are shown. The psoas is deep and close to the spine; and the rectus is on the surface of the abdomen. Ideally the psoas has enough length to allow the pelvis a neutral tilt (as pictured on the left). When the psoas gets overly tight or tense, as it often does when we sit for many hours a day, it pulls the pelvis into a forward tilt (as pictured on the right). OTHER ISSUES ARISE When the psoas is short, a handful of other problems arise. The first two problems come from the forward-tilted pelvis. These are 1) weak and long abdominal muscles (as seen in the picture), and 2) weak and long glutes and hamstrings on the back of the hips. These lead to poor posture and poor digestion, which in turn exacerbate the muscular issues of the abdomen and hips. The other problem that arises with a tight psoas, as you can see in the picture above on the right, is that the low spine gets pulled down and forward toward the pelvis. This creates compression, tenderness and pain in the low back. It also cascades up the spine, creating poor posture in the mid and upper spine, which leads to upper back pain, neck pain and chest pain. WHAT TO DO It is worth saying that sitting less will help the psoas stay long. Things like standing desks are useful to this end. Every hour that we spend sitting encourages the psoas to shorten. It helps to strengthen the abdominal muscles, especially the rectus abdominis. Then the pelvis will have an easier time staying neutral and upright, encouraging a relaxed psoas. Abdominal strengthening, like situps, is invaluable to this end. It also helps to strengthen the glutes and hamstrings with squatting motions. These muscles of the hip will keep the pelvis neutral and encourage the psoas to be long and relaxed. Even if you can't do something like squats or lunges, it helps to do what is called the "Glute Drill", which basically involves squeezing your butt muscles for a few seconds. Do ten squeezes a few times a day and that will go a long way to balancing the psoas.

3 Comments

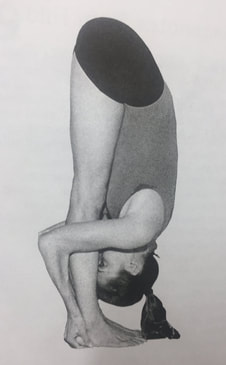

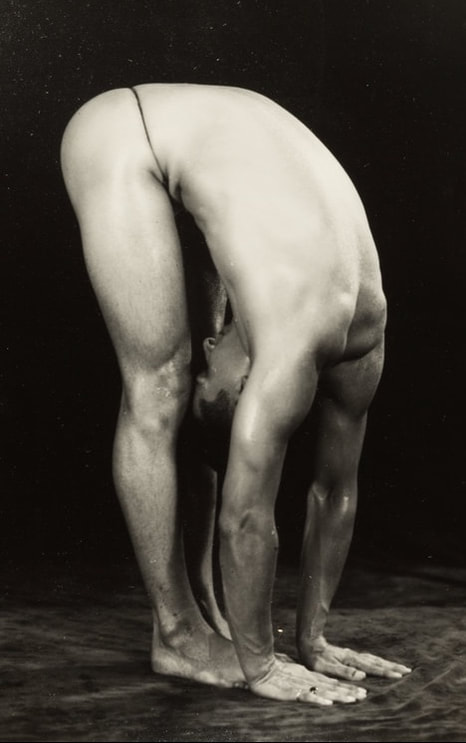

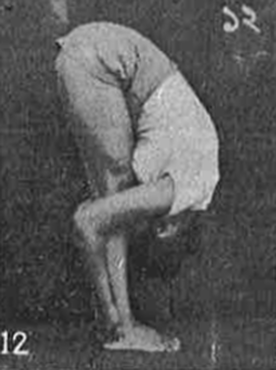

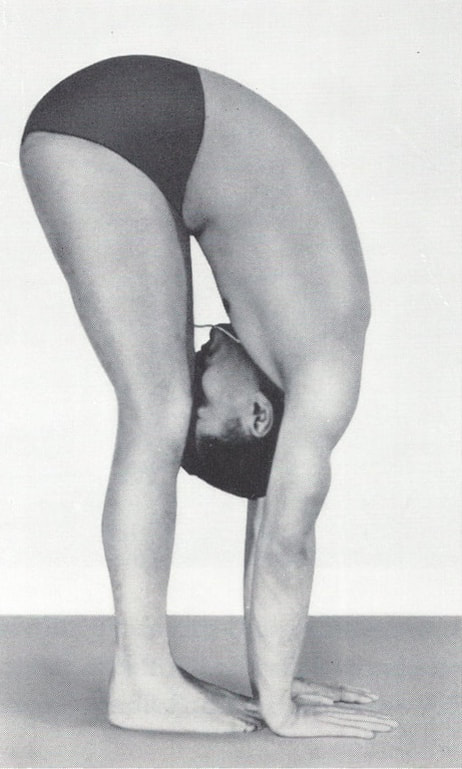

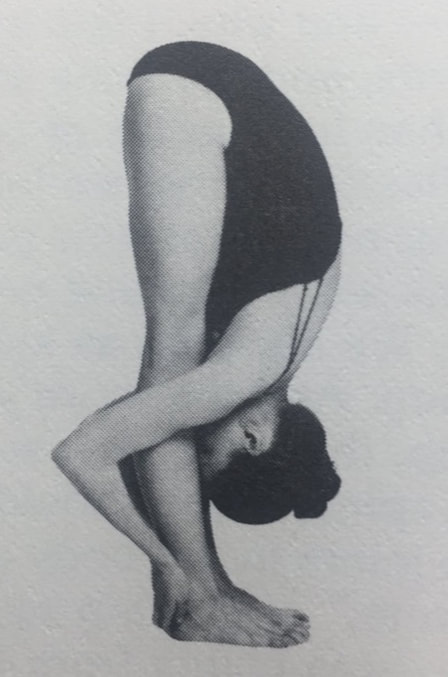

One of the simplest movements in the body is bending forward to touch the toes (not that it is necessarily easy!). This position is often called Padahastasana, which means "Foot Hand Posture", basically putting the hands by the feet. It has been around for nearly as long as any standing, athletic yoga posture, which is to say about 100 years. Its instruction, even within this lineage, has varied slightly. This is an exploration of the evolution of the posture from its earliest known iteration in 1938 to the present day.

From Bikram Choudhury's "Blue" Book, Padahastasana 2000 From Bikram Choudhury's "Blue" Book, Padahastasana 2000 BIKRAM CHOUDHURY, 2000 In 2000, Choudhury published a second edition of his 26-posture sequence. The written instructions are the same, but the position in the accompanying photograph is slightly different, especially the position of the fingers, which are now underneath the heels. THINGS WORTH NOTING Buddha Bose and Dr. Gouri Shankar Mukerji instruct the posture almost identically, with the palms on the floor in front of the feet and the forehead or nose against the knees. Interestingly, they suggest two different methods for anyone with difficulty. Bose suggest slightly bending the legs while Mukerji recommends grasping the ankles with the hands to pull the head toward the legs. Ghosh's 1961 instruction to hold the heels and "pull your body" is almost identical to Choudhury's method. These match Mukerji's instruction when there is difficulty putting the palms on the floor, to "grasp both ankles with the hands" and pull the body down more. The photograph in Choudhury 2000, with the fingers underneath the heels, seems to be an innovation designed to gain more leverage to pull the body down. Interestingly, his written instructions did not change at all from the 1978 version. It is as if there are two different postures being instructed here, clearly distinguished by the distance of the upper body from the legs. Bose and Mukerji emphasize placing the head close to the legs, but their bodies have visible distance from the thighs. Ghosh and Choudhury have instructed postures with the torso touching the legs and using the arms to pull the body into the position. Anyone who has attended one of our classes knows we place great importance on knowing why we are doing what we're doing, whether it is stretching, strengthening, breathing, meditating or eating french fries. This also applies to being a teacher. Why do we/you teach yoga? What do we set out to accomplish, what do we actually accomplish, and is there any discrepancy between those two that can be improved?

We encourage you to respond or comment with your thoughts. As I search my own motivations for teaching, I settle on a relatively simple answer: peace and happiness. These are the things I hope to bring to any students. My goal is at least to point them in the right direction. It will come as no surprise that human existence is interwoven with suffering. Some suffering comes in the shape of desire: wanting things that we do not have and feeling that lack acutely. Some comes in the shape of fear: seeing the possibility for suffering and dreading it. Some comes as depression or stress, and some comes as outright physical pain in the body. More than anything else I've experienced, the teachings and practices of yoga have reduced my suffering. Many physical pains have diminished, but mostly my mental state has improved, bringing contentment where there was dissatisfaction and peace where there was stress. I have become happier. These are the reasons I study and practice yoga; it has made my life better. All around I interact with people who suffer because they are swept up in the chaos of the senses and mind. I talk with people who have goals and desires that bring them pain instead of happiness. And I see people who have injuries or physical pain in their bodies. Through it all, I see how the teachings of yoga could really help to ease the suffering of so many people. The overwhelming activity and power of the mind is common in all humans. It is full of desire and fear, stress and imbalance. Learning about the mind and recognizing its tendencies is one of the fundamental principles of yoga. Over time we can see the activities of the mind as what they are instead of mistaking them for the deepest nature of ourselves. All this is why I teach yoga. I see suffering that has a remedy. I would remiss if I did nothing. So I am compelled to teach. Questions and arguments often arise over the spiritual and religious nature of yoga. Is it spiritual? Is it religious? Is it neither, but a physical exercise regime?

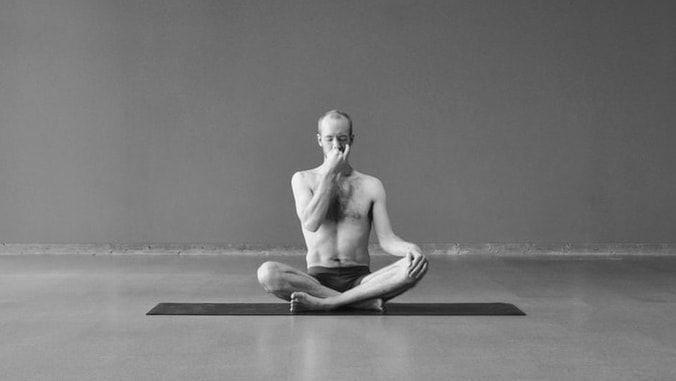

What does it mean to be spiritual? Most spiritual traditions and philosophies address a few important issues: What is the essential nature of the self? What is the essential nature of the universe? Is there God, and if so what is God's nature? Also, what is the relationship between God and us? Each spiritual philosophy and religion has its own answers to these questions. In essence, a religion is defined by its answers to these questions. How does yoga fit in to this? Many people in the West practice yoga for its physical benefits, no different from any exercise regimen. Yoga is great for balance and flexibility, and the calm nature of studios and teachers helps us feel peaceful. For the cardiovascular system yoga is on par with brisk walking, and it has been shown to improve the function of our blood vessels. For many, these physical benefits are more than enough reason to practice yoga. Others practice yoga for spiritual insight, because there is one specific element of spirituality that is clarified by physical activity: the nature of the self. When we control the body, we soon realize that the body is not the truest nature of the self. The self is not defined or limited by the hand or the spine or the stretching feeling in the hamstrings. Deeper still, the self is not defined by the wandering mind, our frustration or ambition to successfully perform a posture or exercise. In this way, physical yoga practices---physical practices of any sort, for that matter---can aid us in understanding the true nature of the self and be spiritual. On the other hand, physical practices including those in yoga have the potential of being devoid of spirituality when the intent is firmly on the physical benefits. So, is yoga spiritual? Yes and no! It depends on your goals, intention and focus. The Dattatreyayogashastra, Dattatreya's Discourse on Yoga, is the first known text to explain a system of hathayoga. There are other descriptions of many of its practices in previous texts, but this is the first time when they are given the title hathayoga. Hathayoga is described alongside three other forms of yoga: mantrayoga, layayoga and rajayoga. Dattātreya said: “Yoga has many forms, o brahmin. I shall explain all that to you: the Yoga of Mantras (mantrayoga), the Yoga of Dissolution (layayoga) and the Yoga of Force (hathayoga). The fourth is the Royal Yoga (rājayoga); it is the best of yogas." - verses 8-11 The sections on the other three forms are brief, but Dattatreya writes in depth about the practices of hathayoga, the yoga of force. Not only that, but the text describes two separate forms of hathayoga: "the yoga of eight auxiliaries known by Yājñavalkya and others" (29), and "the doctrine of adepts such as Kapila" (131). THE YOGA OF EIGHT AUXILIARIES Yajnavalkya's yoga of eight auxiliaries is closely related to the well-known eight part system of Patanjali. It begins with Rules (yama) and Restraints (niyama) and proceeds to Posture (asana), Breath-control (pranayama), Fixation (dharana), Meditation (dhyana) and Absorption (samadhi). It is interesting the Dattatreya references Yajnavalkya but not Patanjali. Of the rules (yamas), "a moderate diet is the single most important, not any of the others. Of the restraints, non-violence is the single most important, not any of the others" (33). Posture (asana) is afforded a healthy couple of paragraphs, mentioning the sacred "84 lakh postures" (34) but describing only one: the Lotus Posture. Breath-control gets the most attention with more than 30 verses. The section describes alternate nostril breathing, advising 20 breath retentions in the morning, 20 at midday, 20 in the evening and 20 at midnight. The final three auxiliaries get relatively brief treatment before the text moves on to the second form of hathayoga. THE WAY OF KAPILA Separate from the above methods are the methods of Kapila, also called hathayoga. "Adepts such as Kapila, on the other hand, practised Force [hatha] in a different manner" (29). "The difference is a difference in practice, but the reward is one and the same" (131). Kapila's methods entail several mudras and bandhas, which involve the combination of physical position---"He should stretch out his right foot and hold it firmly with both hands" (133)---with breath-control---"he should hold [his breath] for as long as he can before exhaling" (134). The purpose of these practices is to move the winds and sacred fluids around the body. PRACTICE It is not stated explicitly if the two forms of hathayoga can be practiced together or whether they should be kept separate. Over the ensuing centuries hathayoga became consolidated, combining the practices of the eight auxiliaries with the mudra practices of Kapila. In modern decades, hathayoga has evolved into a non-specific term meaning "the physical practices of yoga". We will leave you with a final thought from Dattatreya: "[If] diligent, everyone, even the young or the old or the diseased, gradually obtains success in yoga through practice...the wise man endowed with faith who is constantly devoted to his practice obtains complete success. Success happens for he who performs the practices - how could it happen for one who does not?" (40-42). - All quotations are from: James Mallinson, Dattatreya's Discourse on Yoga, 2013.

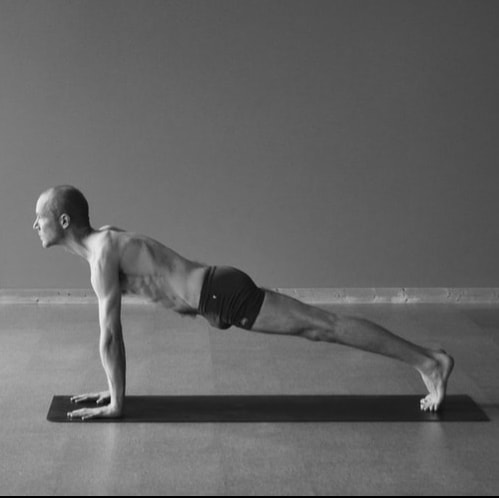

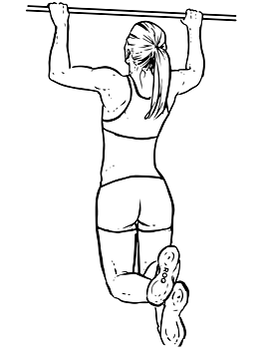

In a yoga class there are many complex and interesting postures to put the body in. They challenge our strength, flexibility, balance, concentration and coordination. It is easy to get lost in fascination with this complexity and lose track of the simplest, most fundamental things our body should be able to do: squatting; sitting up and its opposite; pushing up with the arms; and pulling up.

The opposite of a sit-up is also important. You may call it a back sit-up, back extension or Cobra Posture as it is often named in yoga (pictured at the top of this article). Either way, it involves lying on your abdomen and using your back muscles to bend your spine backward. The combination of these two motions---sit-up and back sit-up (cobra)---will strengthen and stabilize the spine.

These are 5 simple and important movements that every healthy body should be able to do to some degree. If we lose our ability to do these basic movements but still cultivate more complex ones, we are increasingly likely to develop imbalance and injury. Since the physical practices of yoga are about balancing the body more than anything else, it is always worth visiting and revisiting these movements. Without a balanced body, a balanced mind is almost impossible.

On our recent trip to India we visited Kaivalyadhama, the oldest yoga research facility in the world. It was founded by a yogi named Kuvalayananda, who dedicated his life to the three-fold mission of healing people through yoga, teaching the next generation of teachers and researching the scientific impact of the practices. The Kaivalyadhama campus now covers about 200 acres. It has grown from its humble beginnings as a small room for conducting research. As we walked the grounds, we were struck by a quotation from Kuvalayananda: "I have brought up this institute out of nothing. If it goes to nothing, I do not mind, but Yoga should not be diluted." It is a bold statement that shows clear values. Success---in terms of reach, money acquired or people reached---is not important. He goes so far as to say that he doesn't mind if the whole thing disappears!

What was vital to Kuvalayananda was the integrity of the teachings: "Yoga must not be diluted." It takes a strong vision and a strong will to carry out this mission, because it is far too easy to compromise our goals when survival or popularity enter the picture. This shows the intent of a yogi who's thoughts and actions are not swayed by worldly desires. Money comes and goes. Popularity comes and goes. Happiness comes and goes. Even our lives come and go. But knowledge and truth remain. We must not dilute knowledge for the sake of temporary things, even if our institutes go "to nothing". |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed