|

Over the past few years, we have researched the origin and evolution of several postures and practices in this lineage. We thought we would gather them all together in one post, with convenient links.

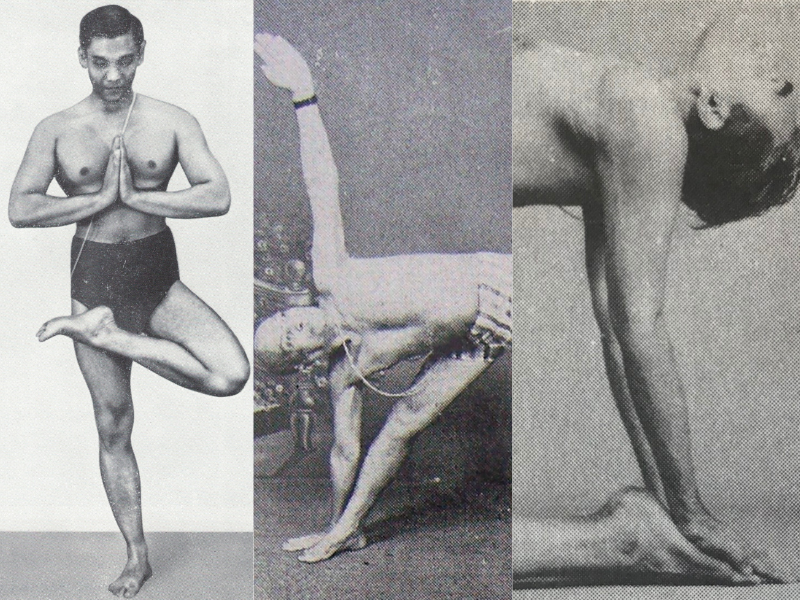

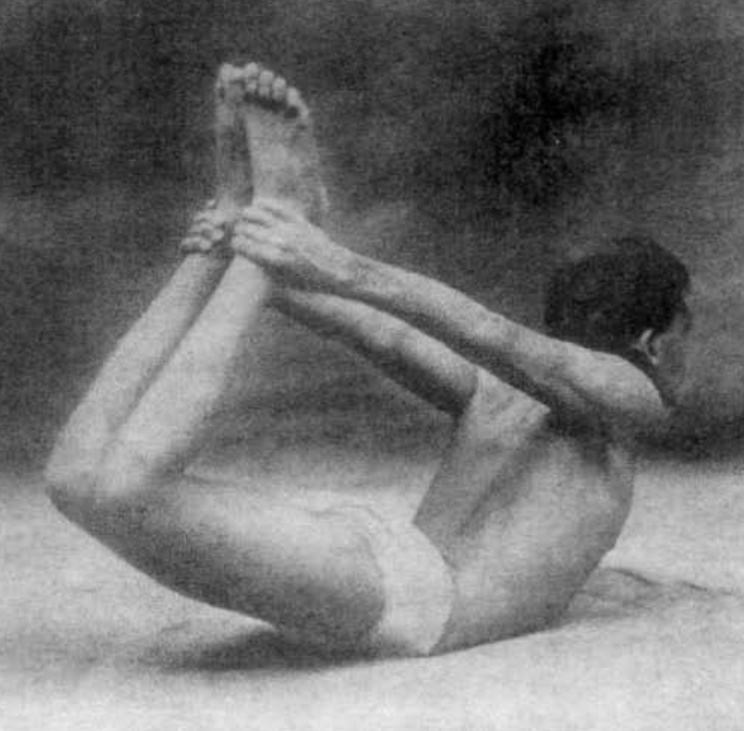

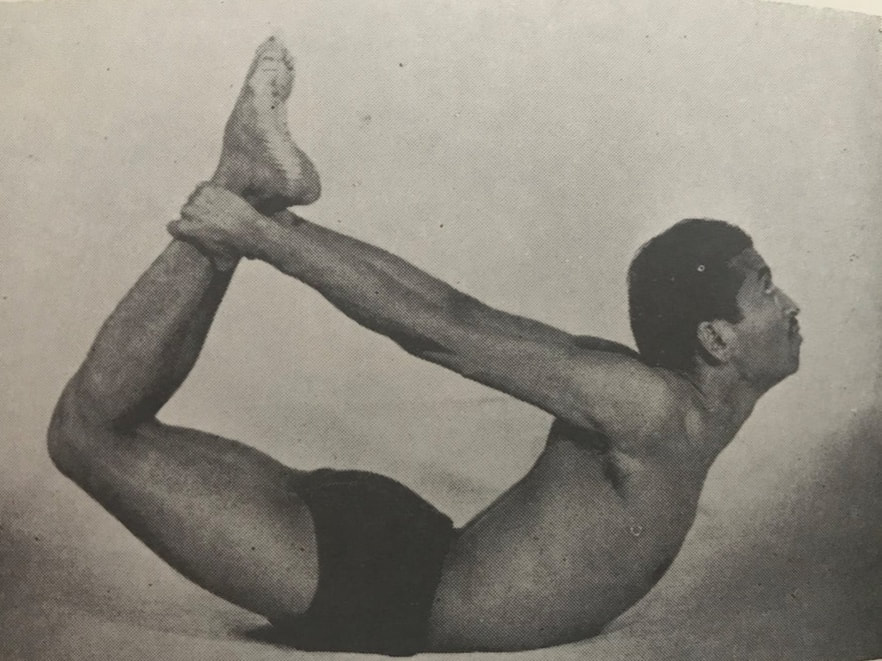

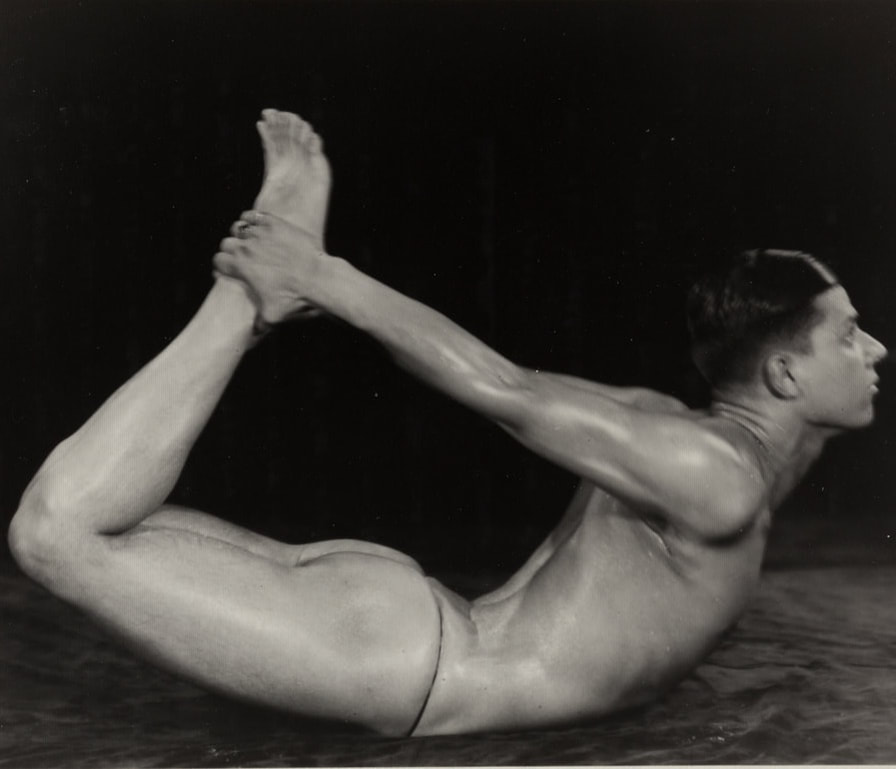

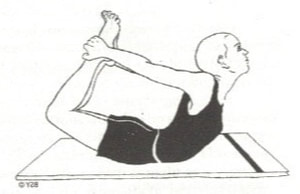

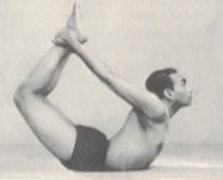

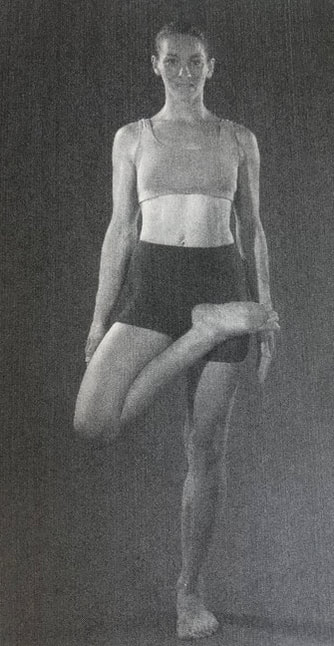

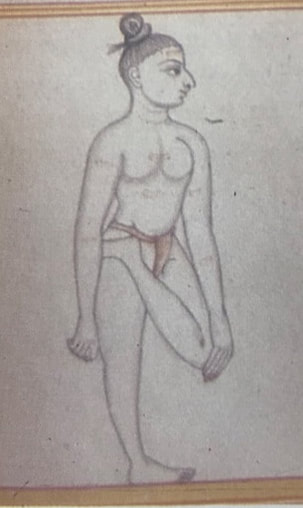

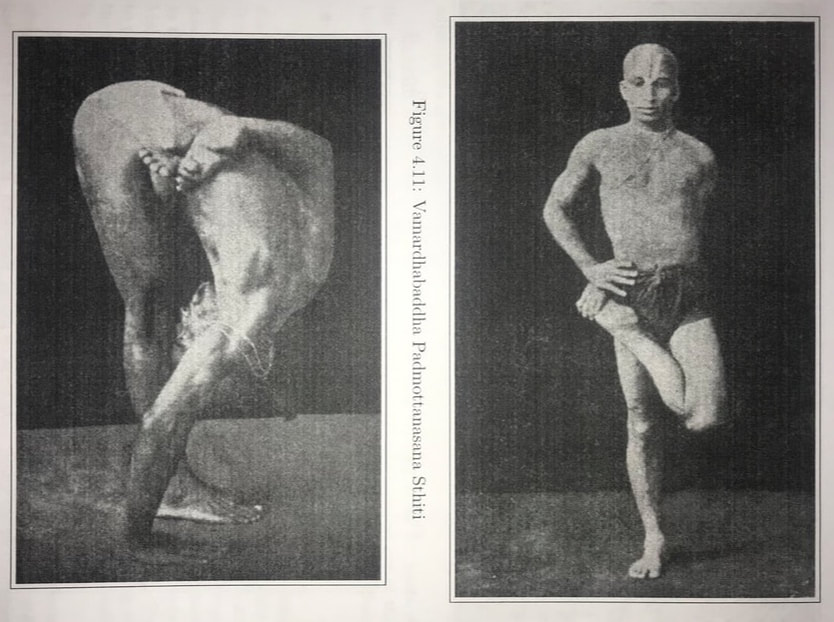

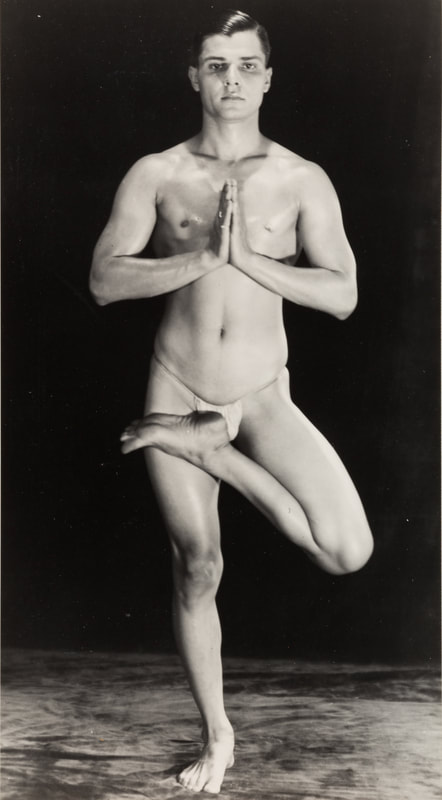

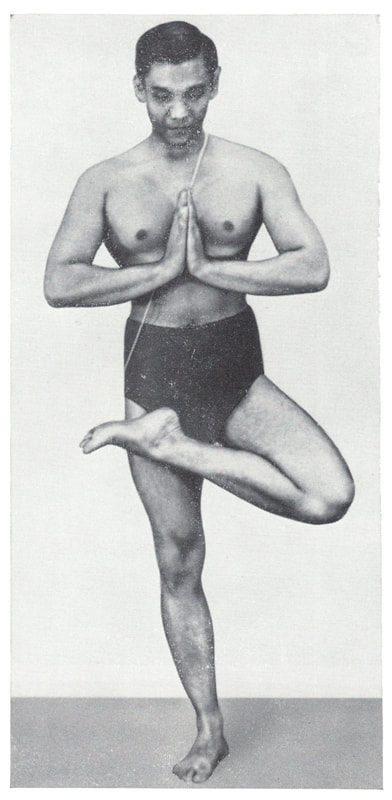

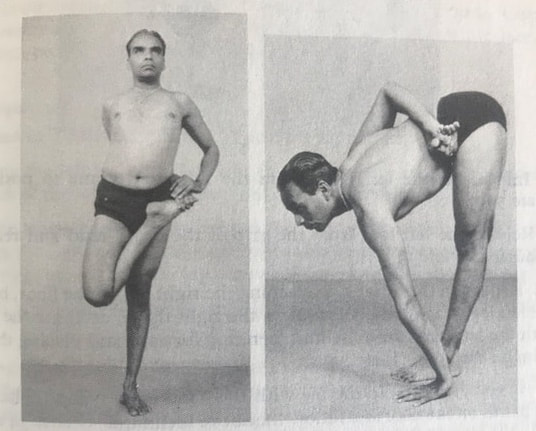

Probably the most significant single piece of research we've done was organizing the postures taught by Bishnu Charan Ghosh and several of his prominent students. We found 113 total postures, with 27 of them that seem to have been central during Ghosh's lifetime. The full list is here, in all its detailed glory. Of course, many of the postures in modern yoga trace back to the late hathayoga era, as physical practice was blossoming. It is noteworthy that all 10 of the older postures in Bikram's class were in the Gheranda Samhita, a text thought to be from Bengal (where Kolkata is). Bow Posture, a staple of modern yoga, seems to have transformed in the 1920s. The posture dhanurasana is explained in hathayoga texts, but it was probably a different posture. Then, the modern backbend came became popular, and is now one of the most recognizable yoga postures. Triangle Posture came into modern yoga in the 1920s, probably under the influence of gymnastics and calisthenics. But it wasn't until the 1970s that Bikram Choudhury transformed the posture into a deep sideways lunge that resembles a bodybuilding pose. Tree Posture is old by any measure. But it has curiously changed names several times, called anything from ardha chandrasana to ardha padasana, vrikshasana to tadasana. Modern Camel Posture, ushtrasana, seemingly came out of nowhere in the 1930s before completely overtaking the older version in the 1960s. Camel Posture has never looked back! Standing Bow Posture is such a new phenomenon that it is hard to even trace where it comes from. Probably some combination of dance and gymnastics, and probably from the south of India. Bikram Choudhury seems to have evolved this posture into its modern form.

0 Comments

Navigating the yoga world can be frustrating. There are so many different styles and so much history underpinning the practices. Not everyone thinks that yoga's history is important, but many find value in the traditions. If you are someone who cares about — or wants to care about — yoga's history and traditions, here are four important concepts, explained as simply as we can.

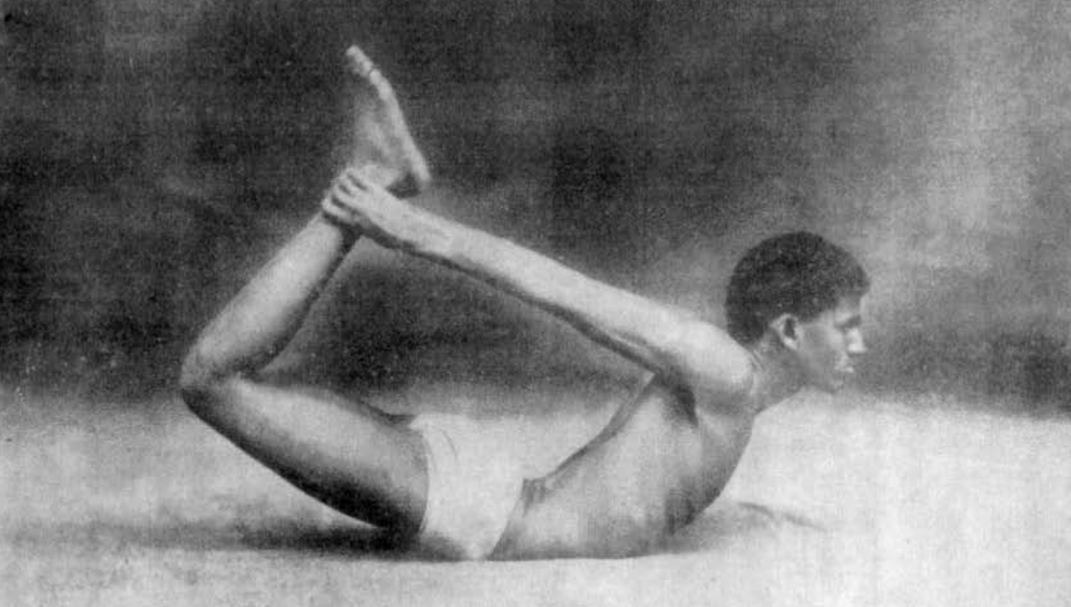

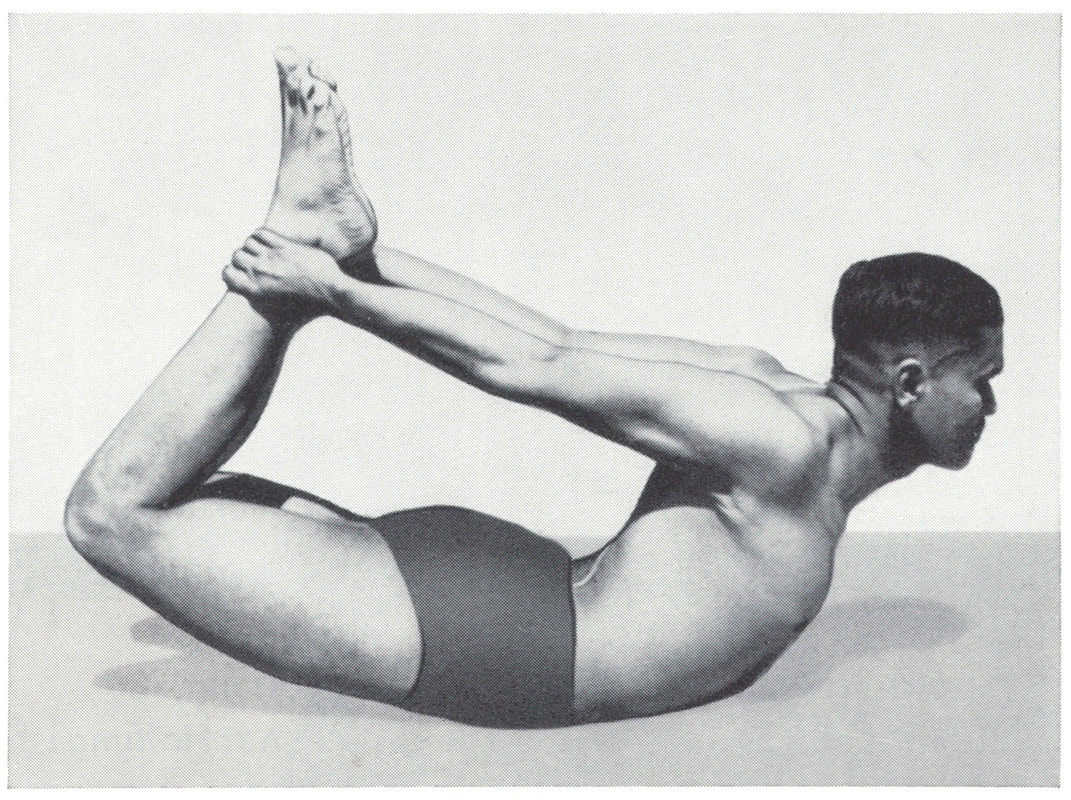

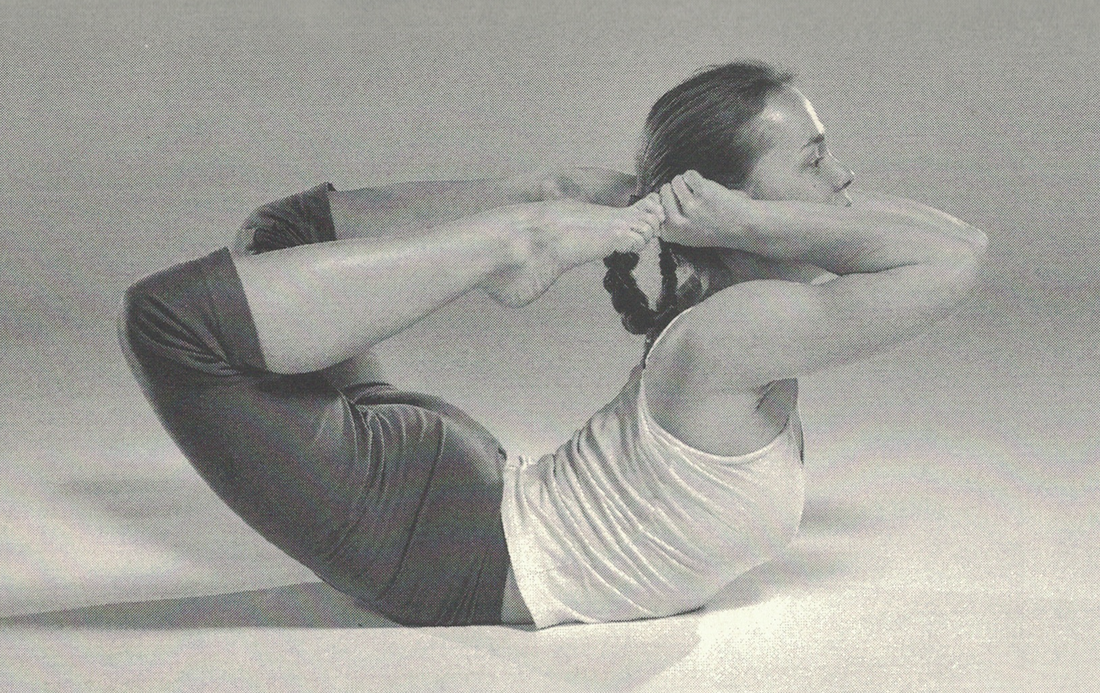

VEDA The word Veda (pronounced vay-duh) means 'knowledge'. This is the name given to the sacred scriptures of Brahmanism/Hinduism. Sometimes these traditions (like Hinduism) are even called Vedic religions because they are largely defined by their reverence for these holy books. The Veda is considered to be revealed knowledge, meaning that it was not written or composed by a human. It was simply written down by humans, sages with special abilities of sight. The knowledge within is thought to be universal, eternal wisdom, something akin to 'the word of God'. UPANISHAD The Upanishads are the last group of books in the Veda. It can help to think of them like the New Testament of the Christian Bible. They are grouped with the rest of the Veda as revealed knowledge, but they present a somewhat different view of the world and spiritual effort. The Upanishads introduce an internal spiritual path, where rituals are carried out in one's own heart rather than externally. This is also where the concept of 'yoga' is introduced, an inward linking of one's awareness to the infinite consciousness within. YOGA Yoga means 'linking' or 'harnessing'. In the Upanishads, where the concept of a spiritual practice named 'yoga' first arises, it refers to linking our awareness within rather than to the world outside. At other times, in more God focused traditions, yoga can refer to linking one's awareness or being with God. In medieval systems of hathayoga, abstract concepts of non-duality became common. Much like the concept of yin and yang, where two opposing forces combine to create balance, yoga could mean the balance of male-female, sun-moon, hot-cold, etc. In this way, many people now define yoga as 'union', which usually refers to some sort of balance or non-duality. In the modern West, most will relate yoga to a physical routine of stretching and relaxation. This type of yoga is pretty new, about a hundred years old. HATHA Hathayoga developed about a thousand years ago. It was a method of using the body to force an effect on consciousness. This is probably why it was called hatha, which means 'force'. A more poetic explanation of hatha developed a little later: it is the union of masculine (ha) and feminine (tha). Much like 'yoga', above, this understanding appeals to balance and unity. In the last couple hundred years, hathayoga has taken on the meaning of 'any physical practices, like postures or breathing'. As such, a lot of modern yoga refers to itself as hathayoga. But modern yoga is a pretty new phenomenon, quite different in practice and belief from the hathayoga of 500 years ago. So most scholars hesitate to call modern yoga hathayoga, instead adopting other labels, like neo-hathayoga or modern postural yoga. Read about the premodern version of Bow Posture, dhanurasana, here. For the past 100 years or so, Bow Posture is done lying on the belly, holding the feet or ankles, and bending the body backward, as pictured above in 1925. Prior to that, the posture seems to have been done sitting and pulling the feet toward the ears. The question remains: Where and when did the posture transition into its modern iteration?

These premodern prone backbends are not called Bow Posture. By 1925 when Yoga Mimamsa publishes instruction, the modern die for dhanurasana seems to be set.

Kuvalayananda's book Popular Yoga Asanas from 1931 also includes Bow Posture, which is no surprise since it is drawn largely from issues of Yoga Mimamsa. Krishnamacharya's Yoga Makaranda in 1934 is curiously devoid of the posture. It makes one wonder about the influence of the Sritattvanidhi above.

Nearly every modern text that we examined contains the posture, from North India's Shivananda lineage, East India's Ghosh lineage, South India's Krishnamacharya lineages, to Europe.

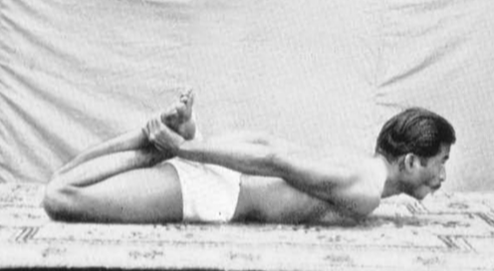

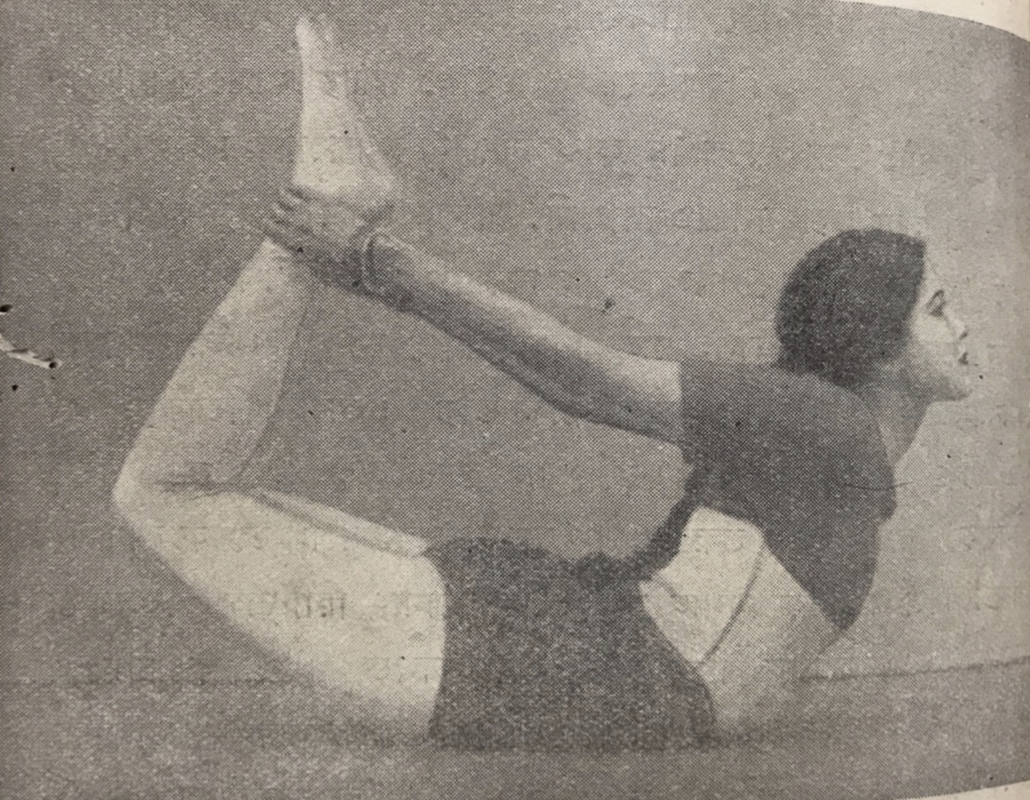

All the students of Bishnu Charan Ghosh include Bow Posture in their instructions. This includes Buddha Bose (above), Labanya Palit in 1955, Ghosh himself in 1961 (demonstrated by his daughter Karuna), Dr Gouri Mukerji in 1963, Monotosh Roy in the 60-70s, and Bikram Choudhury in the late 60s.

Iyengar, in his hugely influential Light On Yoga, is specific about where to carry the body's weight and also to keep the knees slightly apart: "Do not rest either the ribs or the pelvic bones on the floor. Only the abdomen bears the weight of the body on the floor. While raising the legs do not join them at the knees, for then the legs will not be lifted high enough." (Iyengar 1966: 101-2)

The instruction and performance of Bow Posture has been mostly consistent from about the 1920s. It is still unclear when it transitioned from the premodern, seated version into the prone backbend. Its hyper-modern shift to greater depth that resembles contortion more than dhanurasana is also interesting, but a topic for another time.

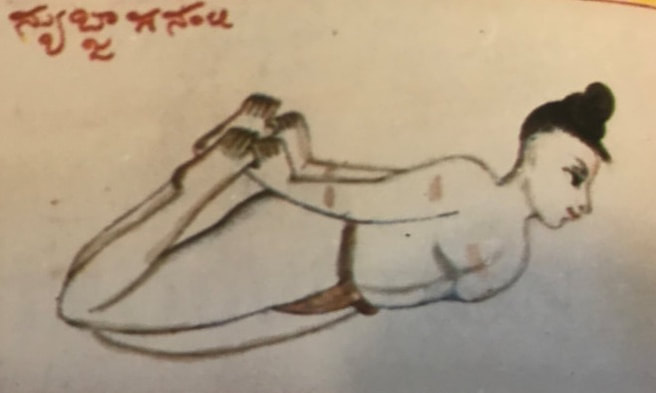

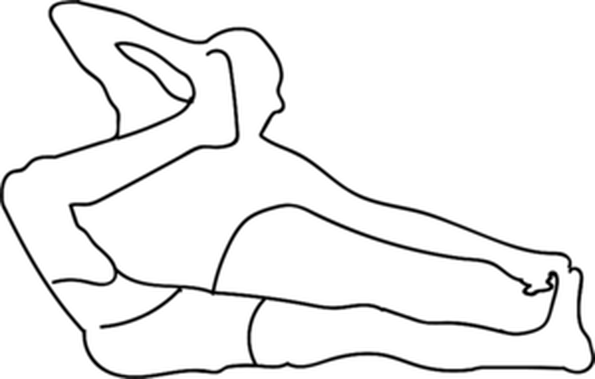

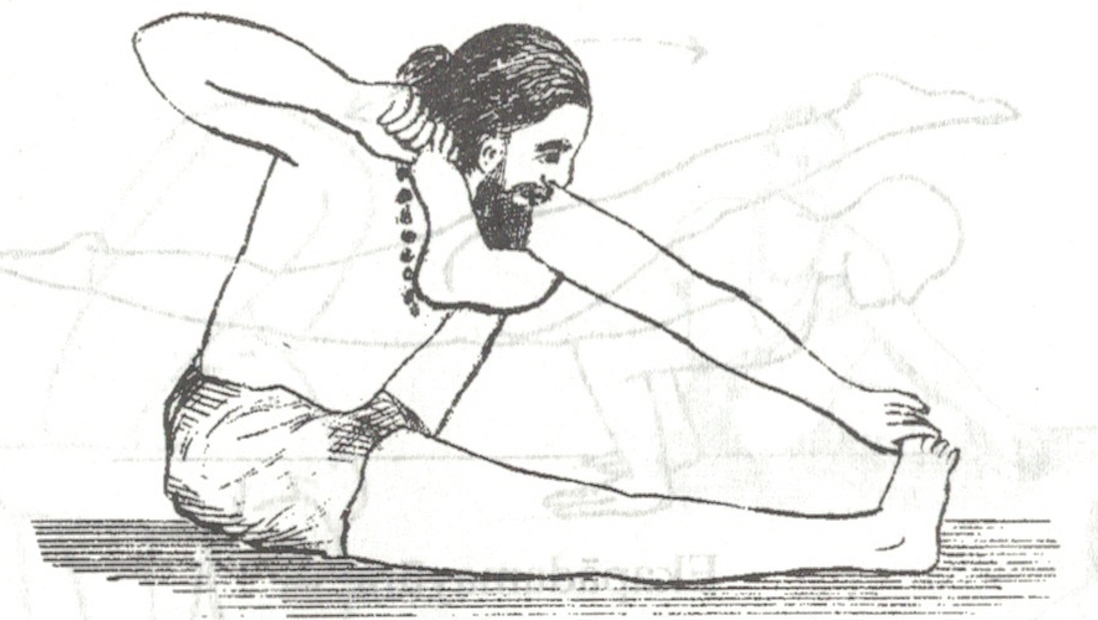

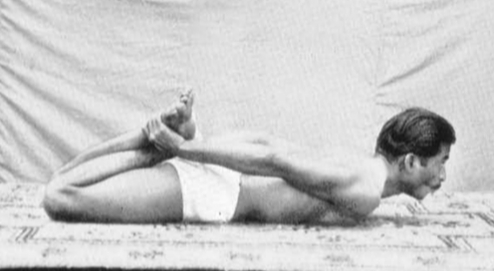

Bow Posture, dhanurasana, is one of the few postures of premodern Hathayoga that is not a seated, cross-legged, meditative position. Its first known instruction is from the 15th century in the Hathapradipika, and it is also included in the 17th century Hatharatnavali and the 18th century Gheranda Samhita. Interestingly, these premodern versions of Bow Posture may be different from the modern understanding. The modern version of Bow Posture, which has been prominent for the past 100 years or so, is done lying on the belly, holding the feet or ankles, and bending the body backward. Prior to that, the posture seems to have been done sitting and pulling the feet toward the ears. Bow Posture's earliest known instruction is in the 15th century Hathapradipika: "Bring the toes as far as the ears with both hands as if drawing a bow. This is Dhanurasana" (HP 1.25). (1) The Hatharatnavali from the 17th century repeats the Sanskrit instructions word for word. Here is a different English translation: "The big toes are held with the hands and are pulled up to the ears (alternately). Thus, one assumes the shape of a stretched bow. This is dhanurasana" (HR 3.51). (2) This posture is done sitting and pulling one foot to the ear as the other leg stays straight, making the body look like a drawn bow. There are two ways that the instruction has been interpreted, depending on whether the hand grabs the foot on the same side of the body or opposite. So this posture has been interpreted as pictured at the top, with the hand pulling the same side foot toward the ear; or with the leg crossing the body as pictured directly above. The instruction is not specific, making it likely that crossing the body is not intended. Nowadays, these positions are still taught sometimes. They are often called akarna dhanurasana, which means Bow to the Ear Posture; or akarshana dhanurasana, which means Bow Pulling Posture.

Bow Posture is also in another well-known premodern text, the Gheranda Samhita, from the 18th century. The instruction has changed a little from the Hathapradipika and Hatharatnavali: "Stretch the legs out on the ground like a stick, extend the arms, hold both feet from behind with the hands, and make the body curved like a bow. That is called Dhanurasana" (GS 2.18). (3) The interesting new instruction here is that the feet are held "from behind". Some interpret this as bending the legs backward and holding the feet, as one does in the modern backbend. But it is entirely possible that this is the same posture as instructed earlier, and the cue to hold the feet from behind is not particularly ground-breaking. The first words in this instruction, to "stretch the legs out on the ground like a stick", are identical to the instructions for Stretching Posture, paschimottanasana. This is perhaps a clue that the Bow Posture in the Gheranda Samhita is intended to be done sitting down with the legs stretched forward.

It seems most likely that the premodern Bow Posture was intended to be seated, pulling the toes toward the ears. The questions arise: When and why did it shift to the modern understanding of a prone backbend? As we will explore next, it seems to be established as the 'modern' Bow Posture by the 1920s.

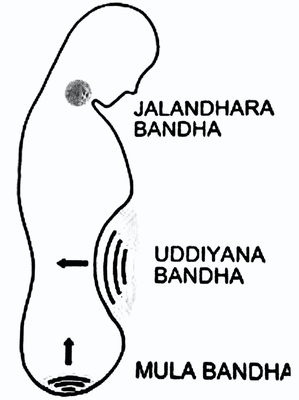

(1) Akers, Brian Dana, trans., 2002 Hatha Yoga Pradipika NY: YogaVidya.com (2) Gharote, M.L., Devnath and Jha, editors, 2014 Hatharatnavali Lonavla Yoga Institute: Pune [2002] (3) Mallinson, James, trans., 2004 Gheranda Samhita NY: YogaVidya.com Mula bandha is a somewhat common technique in modern yoga. It is generally accepted that this technique, which means 'root lock', is a contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor. Some interpret this to be the perineum, the anus, or a combination of the muscles in the pelvis. The anatomical specifics of how and when to do mula bandha are not the goal of this article. Today we are looking at where the practice comes from, and perhaps why it was developed. The instruction of mula bandha dates back to the early days of Hathayoga, around the 12-13th centuries CE. At this time, Hathayoga was gradually forming out of the tantric beliefs of Buddhism and Shaivism. Alchemy, the attempt to forge new substances, was widely accepted, and the spiritual seekers began practicing an 'inner alchemy' where the magic happens inside the body of the yogi. According to this alchemical belief, the inner elements of a person could be forged to create immortality, divinity or great power. As Shaivism (the worship of Shiva) became more prominent in Hathayogic teaching, the concept was related specifically to the awakening of kundalini, a latent power of pure consciousness. The way that kundalini is awakened is by manipulating the 'winds' of the body, some of which naturally go up while others go down. In Hathayoga, mula bandha is specifically intended to take the downward-moving 'wind', called apana, and push it upward. Once the apana wind is turned upward, it is fanned with the abdomen to heat it. Then it combines with the upward wind, called prana. The combination creates an inferno that awakens and raises kundalini. Below is an excerpt from the Hathapradipika, perhaps the best known text on Hathayoga:

As you can see, mula bandha is specifically intended to turn apana upward, where a whole series of events follows. This description of mula bandha is present in almost all the texts of Hathayoga. Here is one other, from the Goraksasataka, translated by James Mallinson. I include it because it is pretty elaborate and well-explained:

This explanation continues to the modern day, though it is rarely incorporated in common yoga posture classes that remove esoteric or spiritual overtones. For obvious reasons, a simple muscular contraction is far easier to teach and understand than a detailed metaphysical system of bodily winds and latent spiritual energy. Nonetheless, Swami Sivananda and his students like Vishnudevananda explain mula bandha similar to the older Hathayogic way. Iyengar, in Light On Yoga, foregoes the apana-kundalini approach and explains mula bandha a little differently. He initially explains the bandhas as closing off "safety valves", which is reminiscent of the old way. But he goes on to interpret the term mula bandha as follows: mula means 'source', and bandha is 'restraint'. So mula bandha is the restraint of the mind, intellect and ego. This recalls Patanjali's famous definition of yoga at the beginning of the Yoga Sutras. Here is what Iyengar writes in Light On Yoga:

We don't think it's a stretch to say that this is a reinterpretation of the meaning of mula bandha. Separately, in modern practice and teaching mula bandha is sometimes taught as a physically stabilizing technique, again quite different from its original iteration.

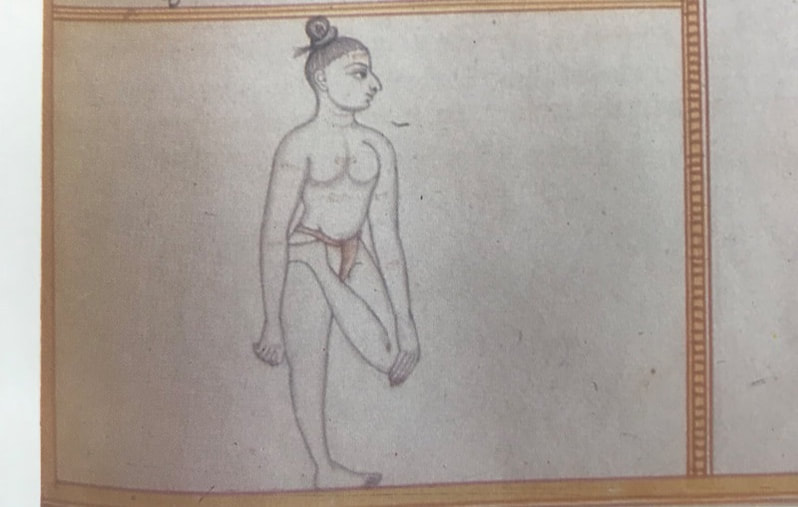

What does it all mean? Like so many things in yoga, the purpose of the practices can change so that they become unrecognizable. Does that make them less effective, useful or valuable? Perhaps. We think it is worth asking ourselves why we do what we do. What are the underlying reasons? Personally speaking, we do not hold the belief that our bodies are populated by 'winds', as was apparently the belief for some time during the development of Hathayoga. We attribute our 'digestive fire' not to actual fire but to hydrochloric acid in the stomach. And we attribute urination and excretion not to downward-moving apana wind but to peristaltic movement of the intestines and contraction of the sphincters. Do these beliefs make something like mula bandha anachronistic? We think that they do. Standing postures are rare in Hatha yoga. Most asanas are seated, lying down or upside down. (Of course, by Hatha yoga I am referring to pre-modern practices and texts. This was before practices of health and exercise made their way into yoga in the 19-20th centuries.) One of the few exceptions is Vrikshasana, the Tree Posture, which appeared relatively late, probably the 18th century in the Gheranda Samhita. Earlier texts including the Hathapradipika don't contain any standing postures.

It can be difficult to know what is real in this world. The methods of yoga, spirituality and science have developed to explore this question. Sometimes they come to the same answers, but sometimes they contradict.

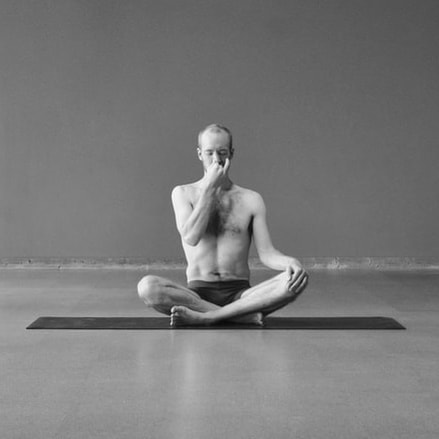

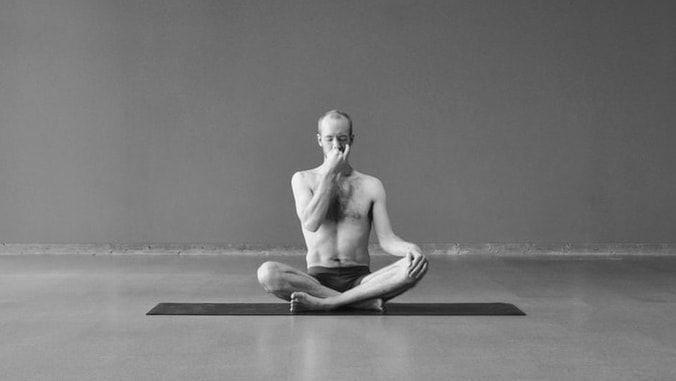

As yoga teachers, we are often confronted with the problems of: 'Why do we do these things?' and 'What is right?' We usually look in three places to find answers: tradition, science and personal experience. TRADITION We at Ghosh Yoga are fascinated with tradition, and we have researched it, studied it, lectured on it and challenged it. We have written about the relationship of oldness and tradition, the Spirit of Tradition, and the sometimes misleading value of tradition. With regards to these questions---what is real? and what is worth learning?---tradition plays an important role in yoga. Many of us are drawn to yoga because of its ancientness, sacredness and gravity. And the idea of lineage, teaching in the same way as you were taught, is a time-worn Indian method that has come to the West with yoga. At its best, a lineage links modern students with ancient teachers and sages. We must take these things seriously. What did our teachers think and what did they teach?If we look in older texts, what was being taught hundreds or thousands of years ago? Most importantly, how do these apply to modernity? Can we extrapolate our own situations, thoughts and perspectives from ancient teachings? SCIENCE In the past few centuries, scientific methods have developed that are centered around the reliability and repeatability outcomes. The sciences have improved our understanding of anatomy, physiology, biomechanics and neurology among other things. We can apply this knowledge to the body and mind in yoga practice. But it can sometimes come into conflict with traditional understanding. For example, humans did not know the intricacies of bodily anatomy until the 15th century CE. This is clearly depicted in art from earlier, where the body is only really understood by looking from the outside. Take this one step further inward, to the functioning of breathing, energy or the nervous system. These things have come into focus even more recently in human history. Therefore, when we look to 'tradition' for physical, anatomical or physiological methods, we must take great care. How does the ancient understanding line up with modern understanding? If there is a discrepancy, is it clear where, why or when that may have occurred? And which do we trust? (For the past few decades, increasing numbers of scientific studies are being done on the practices of yoga. Check out Pure Action.) PERSONAL EXPERIENCE It may seem obvious to say, but all of these practices and traditions of yoga are intended to be put to use by actual living humans, like us. They only come to life when they are studied and executed. Those experiences we have and the inner knowledge we gain are hugely valuable, and one might argue that they are the central purpose of it all. On the other hand, the root of all the spiritual traditions is that our ordinary knowledge and perception are lacking and misleading. We must look deeper and strive to understand what is difficult and hidden. So, partly, our experience is the most important element, but it can also be the most misleading if we are not careful. TAKING THE THREE TOGETHER When assessing the methods and goals of yoga, we constantly weigh the contributions of these three elements: tradition, science and personal experience. There are some instances when all three align. This is the case with Alternate Nostril breathing, a practice described in the ancient texts, explained clearly with the modern scientific understanding of the nervous system, and reinforced by our own experience. We are quite confident in the function of this practice. Other practices are more difficult to justify. Inversions like Headstand and Shoulderstand were originally designed to prevent the falling of bindu from the head into the abdomen. Since that belief has fallen by the wayside, more modern practitioners try to ground the practices in physiological things like blood pressure or thyroid stimulation, which are questionable and unproven to the best of our knowledge. Yogic practices may be anywhere on this scale, swinging from 'traditional' to 'modern', and scientifically proven to completely debunked. Not to mention the experiences we have when we try these things for ourselves. We only suggest that you are considered and thoughtful when practicing yoga. When we practice yoga postures, we might be doing them for different reasons. We may be trying to reduce the pain in our backs, improve our balance, burn a few calories or experience a deeper spirit within. These are drastically different goals, and we can't use the same techniques to achieve them all. Hundreds of "yoga" postures and practices exist these days, and they don't all attain the same things. As you practice, think carefully about what you are trying to accomplish, and use those postures that will help. Here are the 5 different types of yoga postures:

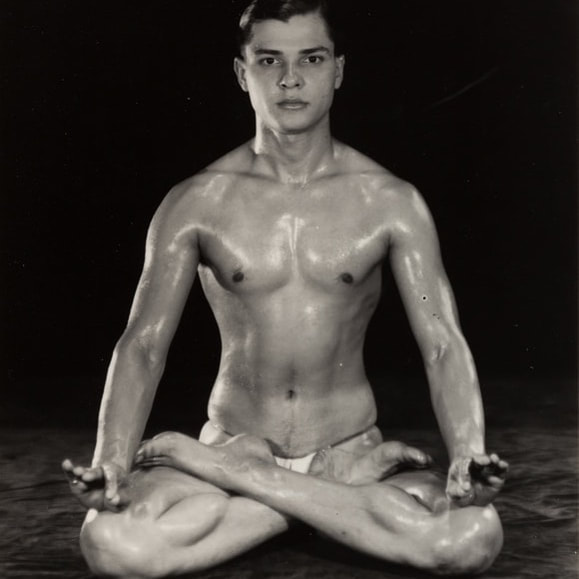

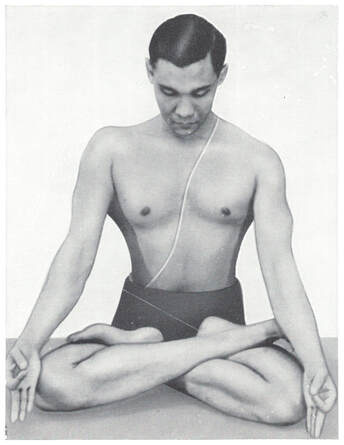

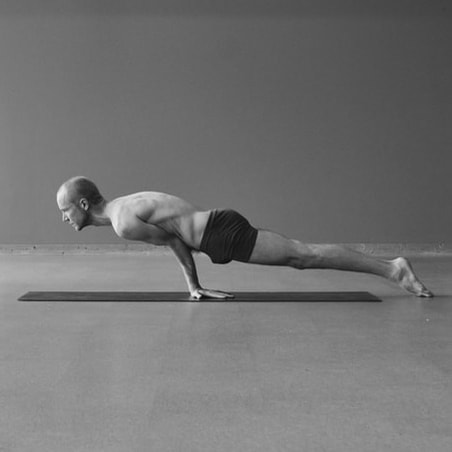

1. Seated, meditation postures. These are the oldest, most traditional yoga postures. When the Yoga Sutras (or any text that is more than 1,000 years old) refer to asanas, this is what they mean: a seated, upright, stable and relaxed position. These positions are not used for their own benefit or to create health, but to facilitate the more internal practices of breath control and meditation. These are the quintessential "yoga postures," Lotus and Siddhasana. 2. Positions to prepare the body for seated meditation or help the body recover from it. As anyone who has tried to sit still for a long period of time knows, it is difficult for the body. A certain amount of flexibility is required in the hips and knees, and some strength and control is required in the spine. How does one build these? Several positions, usually seated, were propagated in early hathayoga to help the body prepare for sitting or recover from the imbalances that arise during sitting. These postures include Cowface, Butterfly, Cobra, Bow and Locust. These are some of the first non-Lotus postures. 3. Anti-gravity postures. Influenced by tantra, hathayoga had many practices that were designed to prevent the precious bindu from dripping out of the head and into the abdominal fire. This was thought to improve vitality, spiritual potency and life. This is where we get the practices that turn the body upside down or "draw upward" the energy, winds or fluids of the body. Headstand, Shoulderstand, Mula Bandha, Uddiyana Bandha, and the upward-focused intention of many postures are intended for this purpose. 4. For physical health. These postures and exercises are much more recent, often coming from calisthenics, gymnastics and wrestling. They build strength, flexibility and health in the body. There are lots of different positions that affect varied parts of the body, so they are vast and diverse. Kuvalayananda called these "cultural" postures. These have become central to the practice of modern yoga. 5. For demonstration and impressive accomplishment. From ancient times, yogis have been associated with the ability to do remarkable feats. In the last couple hundred years, that has increasingly meant physical demonstrations of balance, endurance, strength and flexibility. Influenced by the developments of gymnastics, acrobatics and contortion, these practices include Splits, Handstand and most arm balances. This tendency toward outwardly impressive beauty has been compounded with the rise of photography, the internet and visual communication media like Instagram. Who doesn't love to see a beautiful, impressive picture of a body? One type of posture is not better than the others. There is no hierarchy here, though as yogis some danger lies in focusing on the body and in cultivating techniques for display. Worth noting is that postures can have drastically different purposes, goals and intentions. When we practice them, we should know what we are practicing so we can move in the right direction.  Sometimes yogis talk about "stuck energy" or "moving the energy" of the body. According to some yogic texts, especially in hathayoga, there are subtle channels in the body along which energy moves. It is difficult to determine whether these channels are intended to be purely mental visualizations, descriptions of what we call the nervous system today, or a separate entity altogether. The details of this vast topic are best saved for another time, but here are 5 postures and exercises that are great and moving and affecting the energy: 1. TWISTING TRIANGLE Pictured above, this posture goes right to the areas where most of us feel "stuck," the chest, the hips and the breath. By bending forward and then twisting the body, the posture feels like it makes everything tight. The trick is to release tension with short, calm breaths and a relaxed face. This posture also challenges the balance, which focuses the mind and enables a deeper experience.

The Dattatreyayogashastra, Dattatreya's Discourse on Yoga, is the first known text to explain a system of hathayoga. There are other descriptions of many of its practices in previous texts, but this is the first time when they are given the title hathayoga. Hathayoga is described alongside three other forms of yoga: mantrayoga, layayoga and rajayoga. Dattātreya said: “Yoga has many forms, o brahmin. I shall explain all that to you: the Yoga of Mantras (mantrayoga), the Yoga of Dissolution (layayoga) and the Yoga of Force (hathayoga). The fourth is the Royal Yoga (rājayoga); it is the best of yogas." - verses 8-11 The sections on the other three forms are brief, but Dattatreya writes in depth about the practices of hathayoga, the yoga of force. Not only that, but the text describes two separate forms of hathayoga: "the yoga of eight auxiliaries known by Yājñavalkya and others" (29), and "the doctrine of adepts such as Kapila" (131). THE YOGA OF EIGHT AUXILIARIES Yajnavalkya's yoga of eight auxiliaries is closely related to the well-known eight part system of Patanjali. It begins with Rules (yama) and Restraints (niyama) and proceeds to Posture (asana), Breath-control (pranayama), Fixation (dharana), Meditation (dhyana) and Absorption (samadhi). It is interesting the Dattatreya references Yajnavalkya but not Patanjali. Of the rules (yamas), "a moderate diet is the single most important, not any of the others. Of the restraints, non-violence is the single most important, not any of the others" (33). Posture (asana) is afforded a healthy couple of paragraphs, mentioning the sacred "84 lakh postures" (34) but describing only one: the Lotus Posture. Breath-control gets the most attention with more than 30 verses. The section describes alternate nostril breathing, advising 20 breath retentions in the morning, 20 at midday, 20 in the evening and 20 at midnight. The final three auxiliaries get relatively brief treatment before the text moves on to the second form of hathayoga. THE WAY OF KAPILA Separate from the above methods are the methods of Kapila, also called hathayoga. "Adepts such as Kapila, on the other hand, practised Force [hatha] in a different manner" (29). "The difference is a difference in practice, but the reward is one and the same" (131). Kapila's methods entail several mudras and bandhas, which involve the combination of physical position---"He should stretch out his right foot and hold it firmly with both hands" (133)---with breath-control---"he should hold [his breath] for as long as he can before exhaling" (134). The purpose of these practices is to move the winds and sacred fluids around the body. PRACTICE It is not stated explicitly if the two forms of hathayoga can be practiced together or whether they should be kept separate. Over the ensuing centuries hathayoga became consolidated, combining the practices of the eight auxiliaries with the mudra practices of Kapila. In modern decades, hathayoga has evolved into a non-specific term meaning "the physical practices of yoga". We will leave you with a final thought from Dattatreya: "[If] diligent, everyone, even the young or the old or the diseased, gradually obtains success in yoga through practice...the wise man endowed with faith who is constantly devoted to his practice obtains complete success. Success happens for he who performs the practices - how could it happen for one who does not?" (40-42). - All quotations are from: James Mallinson, Dattatreya's Discourse on Yoga, 2013.

|

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed