|

Ghosh Yoga Teacher Training is four weeks long without stopping. Each day we arise early to do pranayama (breathing) practice, and the day is filled with lecture, discussion, practice and teaching. It is an all-consuming, immersive experience, and it is intended to be that way.

We believe in the immersive approach as opposed to the more sparse (and, admittedly, convenient) approach of weekends or short sessions. The mind is driven by habits, and the strongest habits we have are what we call everyday life. This includes when we get up, what we eat, where we go, what we do, and most importantly, what we think. Yoga practice is above all things a reconfiguring of the habits of the mind. So if we were to spend a day or two in practice and study only to be followed by an entire week of our usual daily habits, the progress made in practice would be undone. The best way to make lasting change in the mind is to undertake new habits for long enough that they stick. Inevitably, we come face to face with our habits after about a week of committed practice. The body and mind resist the transformation, seeking their old, comfortable ways. We feel exhausted and at the end of our rope. But when we persist through this stage, the mind begins to relinquish its old habits and identities. This is when yogis talk about finding "new reservoirs of strength" or "powers I didn't even know I had." In the simplest terms, this is the mind becoming willing to change, especially in terms of who we think we are. Many yoga schools offer the convenience of weekend trainings or a few days per month. There is value in these because they allow people to learn and study while still tending to the necessities of daily life like work and family. But we are firm believers that the practice of yoga is one of recognizing the habits of the mind on the way to changing them. For this to occur, we need to spend significant time committed to practice and study, until our ingrained mental ruts reveal themselves.

0 Comments

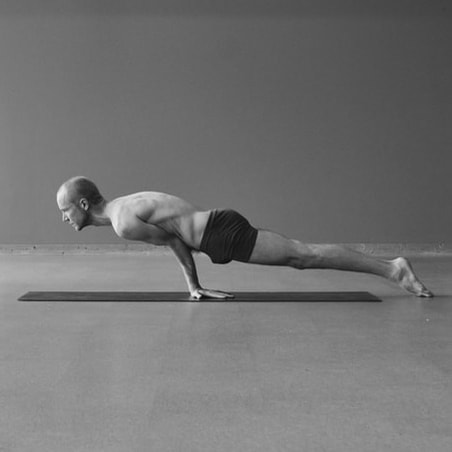

Sometimes yogis talk about "stuck energy" or "moving the energy" of the body. According to some yogic texts, especially in hathayoga, there are subtle channels in the body along which energy moves. It is difficult to determine whether these channels are intended to be purely mental visualizations, descriptions of what we call the nervous system today, or a separate entity altogether. The details of this vast topic are best saved for another time, but here are 5 postures and exercises that are great and moving and affecting the energy: 1. TWISTING TRIANGLE Pictured above, this posture goes right to the areas where most of us feel "stuck," the chest, the hips and the breath. By bending forward and then twisting the body, the posture feels like it makes everything tight. The trick is to release tension with short, calm breaths and a relaxed face. This posture also challenges the balance, which focuses the mind and enables a deeper experience.

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are known as the fundamental text for the system of yoga. They are brief and dense, only 195 short verses, and they can be difficult to understand by themselves.

The sutras are not really intended to be understood without the explanation of a knowledgable teacher, and there is a long tradition of great teachers writing commentaries and explanations of each individual sutra. "Our understanding of Patanjali's text is completely dependent on the interpretations of later commentaries; it is incomprehensible, in places, in its own terms." (1) The first and best-known commentator to explain the sutras was Vyasa, from around the 4th or 5th century CE. Vyasa's commentary is practically inextricable from the sutras themselves and known as the bhashya, which means "commentary." "It cannot be overstated that Yoga philosophy is Patanjali's philosophy as understood and articulated by Vyasa." (2) It has been about 1600 years since the Yoga Sutras were created. In just the past 100-200 years, the understanding of yoga and the sutras themselves has changed somewhat, mostly due to modernization and recent philosophical developments. But in the prior 1500 years the Yoga Sutras were "remarkably consistent in their interpretations of the essential metaphysics of the system." (3) Modern yoga has gotten far from the values of the Yoga Sutras, which focus on the concentration of the mind and emptying its constructed identities to find its underlying reality. Modern interpretations of the Sutras can be shaded by Vedanta---an old Indian belief system that is separate from the Samkhya system of the Yoga Sutras---new-age philosophies and Western modalities. As yogis, the Yoga Sutras have a lot of insight to offer, and the accompanying commentaries are vital to understanding the sutras themselves. So when you pick up a copy of the sutras, try to find one with a traditional commentary. It will help you understand the intended meaning of this important text. 1. Bryant, Edwin. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, North Point Press, New York, 2009, p.xxxviii. 2. Ibid. p.xl 3. Ibid. p.xxxix A huge amount of the sensory and motor processing power of our brain is dedicated to the hands. It is necessary for us to function as we do in the world, picking up objects of various shapes and sizes, carrying things, judging their texture and temperature. But it means that at any given time, the brain has more of its attention focused on our hands than it does on, say, our back.

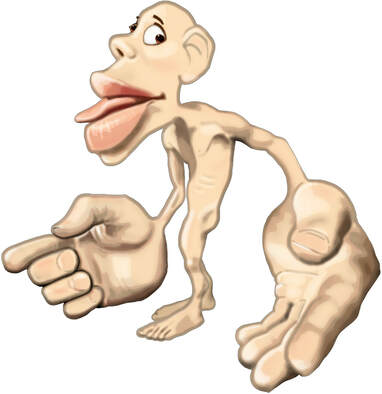

This function of your brain is represented by the picture above, called the Homunculus. It represents the amount of the brain's sensory power that is dedicated to each part of the body, with greater attention displayed by larger features. The results end up being almost obvious, with a lot of the brain's sensory attention focused on the lips and tongue, eyes and ears, genitals, hands and feet. These are the most sensitive parts of the body. What does this mean for us as yogis? In general, it means that it's easy for us to think about our hands. We may be doing an exercise that is focused on the spine, but we will wonder, "What do I do with my hands?" Or while we are balancing or breathing, "How should I hold my hands?" It is easy for our brains to answer this call, since it likes to put its attention on the hands. But this makes it harder to focus on things---parts of the body or mind---that are not the hands. It is difficult to take the attention away from the hands and put it on the spine or abdomen, or knees. Next time you do (or teach) a posture, check how much of your focus you put on the hands, their grip and their position. Then ask yourself if they are the central focus of the exercise. See if you can move your attention and effort away from the hands to the part that is most important for each practice. It can be challenging at first, but tremendously beneficial. Knowledge is power. Our understanding of the world around us and our place in it directly affects our ability to function effectively and attain happiness or success (or both), or whatever it is that we seek. As a teacher you pass information and the ability to think to your students, making them more powerful. The better you are as a teacher and the more knowledge you provide, the more powerful your students will become.

This power dynamic can create tension between the teacher and student. Many teachers are afraid of the power that the student will gain if they offer all their knowledge. Won't the student then be equal to the teacher? Or perhaps even better? So the teacher limits the knowledge they offer, only providing part of the information to prevent the student from rising too high. Or they may belittle their students, criticizing and insulting them to remind the students how low they are. This keeps the student---in the teacher's mind, at least---below the teacher. How do we avoid this? By embracing the possibility that our students will become greater than us. Hoping for it. The value of our students is not in the way they build us up, looking up to us admiringly as all-knowing gurus. The value of our students is the way they are individuals with unique experiences, minds and ability to think. Their value is the same as ours, the same as anyone's, to recognize the things that need to be done to make the world better. To have the knowledge and courage to pursue them. One of our favorite quotations is credited to Ralph Waldo Emerson, "The greatest way to honor one's teacher is to obliterate him." This contains a great lesson for the student and the teacher. The goal of both parties is the transfer of knowledge and understanding, which is not to be confused with doing things the way they've always been done. A successful student will be able to think independently of the teacher. A successful teacher will embrace and encourage that independence. As the year turns over, we quickly shift from looking backward---"what happened this year?"---to looking forward. I have mixed feelings about New Year's resolutions because they encourage us to be dissatisfied. It would be better to focus on contentment.

The more I practice, teach and study I am shocked by the way my mind changes. I see things so differently now than I did when I started learning about yoga years ago. I suppose it shouldn't be surprising. How could we possibly have clear vision or intention when we are beginning on a new path? Each bit of practical experience and insight necessarily changes our perspective. Lately, I have been studying the Bhagavad-gita, and it is so clear which passages are speaking to my present situation: Actions should not be undertaken for the benefit of myself or my ego. When I say this out loud, it seems obvious and silly. But which of our actions are not designed to benefit ourselves? When I say things so people understand my intelligence, I am serving my ego. When I eat the food I "like," I am serving my sensory desire. Even when I study and learn, am I doing it just to develop my sense of accomplishment and my ability to excel in the world? It is increasingly important to me to recognize and subvert these thoughts and actions. Instead, my actions should be directed toward the service of others. The difficult part for me to understand is do I do this for the benefit of myself or other people? Even that dilemma is addressed in the Gita. One who performs apparently selfless actions for his own benefit is ignorant, while one who takes no credit and accepts no personal benefit is wise. This is my goal: to serve with no agenda. To recognize the emergence of my ego and discard it, so my actions build the good of the world at large instead of just myself. This blog was originally written in January 2019. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed