|

Over the years, we have come up with what we call perfect postures. We consider postures perfect, when they follow these three rules:

Let's look at these criteria in more detail. THE CORRECT MUSCLES HAVE TO ENGAGE In many of the postures we practice, it is easy to get the wrong muscles involved. Standing Head to Knee (with the arms) is a perfect example. Standing Head to Knee should be a balancing forward bend of the spine. However, with the arms, it's almost inevitable that the arms engage to hold the leg up and pull the upper body closer to the leg. Also, the back often engages to prevent us from collapsing all the way forward. Both of these actions will not take us in the direction of the pose for the following reasons: 1) The arms do not bend the spine forward, that's the job of the rectus abdominis. 2) A forward bend of the spine requires abdominal engagement and back relaxation. If our back is engaging, this is the opposite of the pose. This brings us to the first perfect pose, Standing Head to Knee with No Arms. While it is incredibly difficult, any attempt to balance on one leg, lift the other and round the spine will take us in the right direction because the correct muscles have to engage. NO EXTREME RANGE OF MOTION IN THE BODY The second rule for a perfect posture is no extreme range of motion. In some ways, postures with small ranges of motion are easy to find. On the other hand, yoga postures can easily incorporate extreme ranges of motion without us realizing it. This is something we have to be careful of. Our next two perfect poses are Full Locust and Locust. In addition to the other criteria, they do not ask for any extreme range of motion.  WITHOUT THE STRENGTH TO DO THE POSTURE, NOTHING HAPPENS The last rule that makes a posture perfect relates to what happens when we don't have the strength to execute the posture. In some postures, if we don't have the strength or control, we can get ourselves into a sticky situation. Examples of this could be a position that puts a lot of stress on a joint or a pose that lengthens a muscle too far. In a perfect posture, if you don't have the strength to do the posture, nothing happens! It is perfectly safe for this reason. The final two perfect postures are Palmstand and Torso Lift. Anyone who has tried Palmstand for the first time will likely remember the feeling of "Nothing is happening!" While it is difficult to lift the hips and legs up, it's completely safe. Without the strength, we simply remain sitting. The same principle applies to Torso Lift. Without abdominal strength, nothing happens.

0 Comments

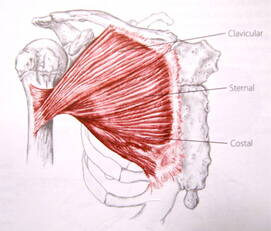

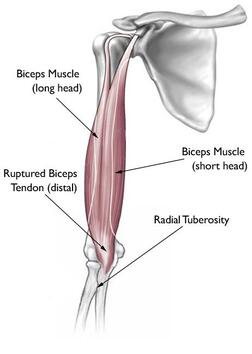

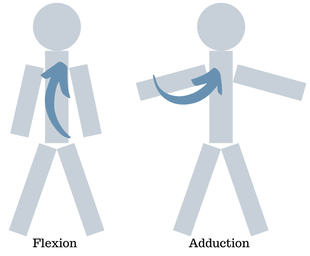

This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. Last month we wrote about the common shoulder injury Shoulder Impingement. The other common injury to the shoulder happens in the front, where the short head of the biceps muscle attaches to the shoulder blade, a biceps tendon strain. This injury is most common in Ashtanga Vinyasa and subsequent 'flowing' yoga styles that incorporate a lot of Sun Salutations and chaturangas. The shoulder can't do this action very well, and the biceps become strained before too long.  Pectoralis major ("pec") Pectoralis major ("pec") To understand this injury, we have to talk about shoulder mechanics and the muscles that move the arm. PECTORALIS MAJOR & ADDUCTION One of the biggest and most powerful muscles of the shoulder is the pectoralis major, commonly known as the 'pecs' or just the 'chest muscle', pictured to the left. It connects the arm (humerus) directly to the middle of the chest. Its main function is to pull the arm toward the chest in an action called adduction. Try it: hold your arm out to the side (as pictured below, labeled adduction), then bring your arm toward the center, so you end up with your arm pointing forward. As you do this, you will feel your 'pec' engage. When you apply this motion to something like a pushup, the arms need to be away from the body, so the pushup motion will be pulling the arm inward toward the chest. Simply put, this means keeping your elbows away from the body. This is the safest way to do any pushup motion.  BICEPS & FLEXION In contrast, if we start with our arms down by the sides and lift them up until they point forward, this is called flexion (pictured above, labeled flexion). When we lift the arm like this, the pec doesn't get activated much, so the work is done by much smaller muscles like the anterior deltoid (the front of the shoulder cap) and the biceps. The biceps cross two joints; they bend the elbow and also flex the shoulder. But they don't have the power to move the body's entire weight. When we do pushups or chaturangas with the elbows close to the sides of the body, we are essentially moving the shoulder in flexion. This is not a powerful nor particularly healthy way to move so much weight. When we do this repeatedly, the bicep tendon (usually the short head at the attachment with the coracoid process of the shoulder blade) will often be damaged. This manifests as pain or soreness in the front of the shoulder. There is a common belief that keeping the elbows close to the body uses the triceps more than if the elbows were wider. This is not true for the simple reason that the triceps straighten the elbow, and the elbow is doing a similar action in both versions. The big impact is on the shoulder and what muscle group you use when doing a pushup or chaturanga motion. IN CONCLUSION There is nothing inherently wrong with keeping the elbows close to the body and flexing the shoulder. The problems arise when we do this with our entire body weight and do it repetitively. This is how injury usually happens. Consider making the elbows wider, which will strengthen the huge pectoralis major muscle as well as be safer for the smaller muscles of the shoulder. Happy, healthy practicing! We're about halfway through the Ghosh 2020 challenge! Each day we've been posting a concept related to the physical practice. Occasionally, we've asked you to respond to questions about how these postures function in the body. This challenge is all about being clear about the goals of the practice and how they're accomplished. With this in mind, we'd like to address a common misconception about breathing.

When we breathe in the chest (like in Standing Deep Breathing), the abdominal muscles are relaxed. This seems to confuse a lot of people who are used to hearing "suck the stomach in" or something like it in this exercise. When we inhale into the chest, we use the intercostal muscles between the ribs and not the abdomen. (More on that here.) The abdomen does appear to come in, but this is directly a result of the chest lifting. There is no action in the abdominal muscles on the inhale. Muscles only have the ability to pull. They cannot push. When a muscle engages, it pulls its two attachment points closer together. So, no action in the abdomen can push the ribs up. (In fact, engaging the rectus abdominis will keep us from affectively breathing in the chest, because it will pull our ribs down.) In chest breathing, we have a second set of intercostal muscles that exhale. However, it is true that the transverse abdominis can help us exhale, especially if we are exhaling forcefully. When you practice chest breathing, relax your abdomen. On the inhale, any muscular effort in the abdomen will hinder you. Samadhi is an important concept in yoga. It is the highest of the 8 'limbs' in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and the highest of the 6 'limbs' of the Maitri Upanishad. Even with such a distinguished position as the culmination of yogic practice, it is a difficult concept to understand. Often samadhi is described as 'absorption', 'meditation', or 'contemplation'. I think it is much clearer to think of it as 'transparency of mind'.

One of difficulties with samadhi is the same as will arise with any other word. Most words have multiple meanings, and it can be a challenge to pinpoint the correct one. Samadhi is often used in a more general sense meaning 'concentration'. So we often see it used in contemplative, yogic and spiritual texts without a super technical purpose. Often it just means concentration. But in yoga texts around 0-500 CE, samadhi took on a more specific, technical meaning. It was placed atop of the pyramid of meditative practice, above the older, better-known dhyana, which was until then a more common term for meditation. THE COLOR OF THE MIND To understand the value of samadhi, first we must understand the nature of the mind. As a thinking and perceiving tool, the mind is always interpreting what it sees and combining it with what it has experienced in the past. This interaction of the present with our memory is what gives us our 'reality'. But it is dependent on our past experience and the beliefs it has created. So we are not actually experiencing the world as it truly is but interpreting it through the lens of our own history. The mind is like stained glass. We can see the world on the other side, but it is distorted and colored by our own experience, history and memory. The practice of yoga is largely committed to reducing the 'color' of the mind, working toward removing the distortions of our perception and the impact of the mind's own tendencies on our interaction with the world. A TRANSPARENT JEWEL Samadhi is the ultimate expression of mental transparency, where the mind no longer interprets the world through a 'colored' filter. As it says in the Yoga Sutras, "the mind becomes just like a transparent jewel, taking the form of whatever object is placed before it" (YS 1.41). This means that there is no distortion whatsoever caused by the mind, and we can experience each object exactly as it is without our own interpretation. Similarly, samadhi is described later in the sutras as the state when "the mind is devoid of its own reflective nature" (3.3). This is a difficult state to achieve, as the tendency of the mind is mostly toward interpretation. Meditative practices are largely aimed at solving this problem by encouraging a 'one-pointed' mind. This reduces the tendency of the mind to think, interpret and color our perceptions. The culmination, samadhi, is when we cease to interpret the world, make the mind transparent, and experience the world as it is. A while back, Calcutta Yoga by Jerome Armstrong was available on this site. The limited run sold out quickly and as it did, the book was picked up by Pan MacMillan Publishing. The wait for the new and improved version is over! Calcutta Yoga comes out soon and you can order it here.

Calcutta Yoga is the story of Buddha Bose, Bishnu Ghosh, Yogananda. Heavily researched, the book chronicles yoga in Calcutta in the early 1900s and follows it as it spreads beyond Bengal and into the world. Where one story bled into the next, Jerome followed through leaving no stone unturned. This book is the culmination of years of effort and a worldwide quest to get to the bottom of the history of Calcutta Yoga. For now, the book will be out as a hardcover in India, and available as an ebook worldwide. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed