|

Usually we write about yoga topics like anatomy, philosophy, history and such. Today we have a different purpose, because these are extraordinary times. This morning we got the first dose of the Moderna COVID vaccine. In Northern Minnesota, about an hour from where we live, is a large vaccination site. It is in a curling arena, right next door to the National Hockey Hall of Fame. In the past few days, word began spreading that they were not filling the available appointments for vaccine shots. One day it was 30 slots that went unfilled, and yesterday it was 400, which is about half of the capacity of the site. So, in order to vaccinate as many people as possible, they encouraged anyone to make an appointment and come, regardless of age (as long as you're over 18, of course).

Scientific experts say that this pandemic will only end when the world reaches herd immunity. Vaccination plays a pivotal role in that goal. Leaders have also encouraged us to talk about getting vaccinated and post pictures, since some still fear or distrust vaccines or consider them pointless. Throughout this pandemic, we have made an effort to listen to respected scientific leaders and follow their advice. We are relatively young and healthy, but it is clear that our actions affect others who are more vulnerable, including our own parents, grandparents and families. In order to do our part, we (like so many others) drastically changed our lives over the past year. We thought that we would have to wait until the summer to get the vaccine, due to our age and health histories. We were fortunate to have this opportunity to get vaccinated, and we took it! We hope that you and your loved ones (and everybody else too) gets vaccinated as soon as you can.

0 Comments

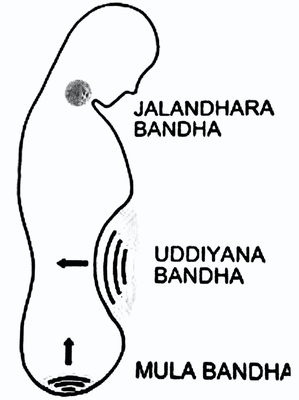

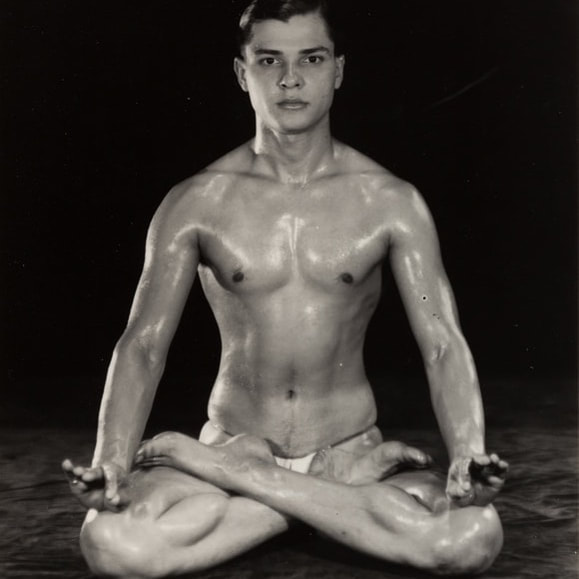

Mula bandha is a somewhat common technique in modern yoga. It is generally accepted that this technique, which means 'root lock', is a contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor. Some interpret this to be the perineum, the anus, or a combination of the muscles in the pelvis. The anatomical specifics of how and when to do mula bandha are not the goal of this article. Today we are looking at where the practice comes from, and perhaps why it was developed. The instruction of mula bandha dates back to the early days of Hathayoga, around the 12-13th centuries CE. At this time, Hathayoga was gradually forming out of the tantric beliefs of Buddhism and Shaivism. Alchemy, the attempt to forge new substances, was widely accepted, and the spiritual seekers began practicing an 'inner alchemy' where the magic happens inside the body of the yogi. According to this alchemical belief, the inner elements of a person could be forged to create immortality, divinity or great power. As Shaivism (the worship of Shiva) became more prominent in Hathayogic teaching, the concept was related specifically to the awakening of kundalini, a latent power of pure consciousness. The way that kundalini is awakened is by manipulating the 'winds' of the body, some of which naturally go up while others go down. In Hathayoga, mula bandha is specifically intended to take the downward-moving 'wind', called apana, and push it upward. Once the apana wind is turned upward, it is fanned with the abdomen to heat it. Then it combines with the upward wind, called prana. The combination creates an inferno that awakens and raises kundalini. Below is an excerpt from the Hathapradipika, perhaps the best known text on Hathayoga:

As you can see, mula bandha is specifically intended to turn apana upward, where a whole series of events follows. This description of mula bandha is present in almost all the texts of Hathayoga. Here is one other, from the Goraksasataka, translated by James Mallinson. I include it because it is pretty elaborate and well-explained:

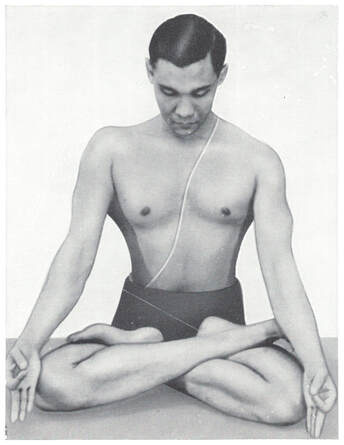

This explanation continues to the modern day, though it is rarely incorporated in common yoga posture classes that remove esoteric or spiritual overtones. For obvious reasons, a simple muscular contraction is far easier to teach and understand than a detailed metaphysical system of bodily winds and latent spiritual energy. Nonetheless, Swami Sivananda and his students like Vishnudevananda explain mula bandha similar to the older Hathayogic way. Iyengar, in Light On Yoga, foregoes the apana-kundalini approach and explains mula bandha a little differently. He initially explains the bandhas as closing off "safety valves", which is reminiscent of the old way. But he goes on to interpret the term mula bandha as follows: mula means 'source', and bandha is 'restraint'. So mula bandha is the restraint of the mind, intellect and ego. This recalls Patanjali's famous definition of yoga at the beginning of the Yoga Sutras. Here is what Iyengar writes in Light On Yoga:

We don't think it's a stretch to say that this is a reinterpretation of the meaning of mula bandha. Separately, in modern practice and teaching mula bandha is sometimes taught as a physically stabilizing technique, again quite different from its original iteration.

What does it all mean? Like so many things in yoga, the purpose of the practices can change so that they become unrecognizable. Does that make them less effective, useful or valuable? Perhaps. We think it is worth asking ourselves why we do what we do. What are the underlying reasons? Personally speaking, we do not hold the belief that our bodies are populated by 'winds', as was apparently the belief for some time during the development of Hathayoga. We attribute our 'digestive fire' not to actual fire but to hydrochloric acid in the stomach. And we attribute urination and excretion not to downward-moving apana wind but to peristaltic movement of the intestines and contraction of the sphincters. Do these beliefs make something like mula bandha anachronistic? We think that they do. It can be difficult to know what is real in this world. The methods of yoga, spirituality and science have developed to explore this question. Sometimes they come to the same answers, but sometimes they contradict.

As yoga teachers, we are often confronted with the problems of: 'Why do we do these things?' and 'What is right?' We usually look in three places to find answers: tradition, science and personal experience. TRADITION We at Ghosh Yoga are fascinated with tradition, and we have researched it, studied it, lectured on it and challenged it. We have written about the relationship of oldness and tradition, the Spirit of Tradition, and the sometimes misleading value of tradition. With regards to these questions---what is real? and what is worth learning?---tradition plays an important role in yoga. Many of us are drawn to yoga because of its ancientness, sacredness and gravity. And the idea of lineage, teaching in the same way as you were taught, is a time-worn Indian method that has come to the West with yoga. At its best, a lineage links modern students with ancient teachers and sages. We must take these things seriously. What did our teachers think and what did they teach?If we look in older texts, what was being taught hundreds or thousands of years ago? Most importantly, how do these apply to modernity? Can we extrapolate our own situations, thoughts and perspectives from ancient teachings? SCIENCE In the past few centuries, scientific methods have developed that are centered around the reliability and repeatability outcomes. The sciences have improved our understanding of anatomy, physiology, biomechanics and neurology among other things. We can apply this knowledge to the body and mind in yoga practice. But it can sometimes come into conflict with traditional understanding. For example, humans did not know the intricacies of bodily anatomy until the 15th century CE. This is clearly depicted in art from earlier, where the body is only really understood by looking from the outside. Take this one step further inward, to the functioning of breathing, energy or the nervous system. These things have come into focus even more recently in human history. Therefore, when we look to 'tradition' for physical, anatomical or physiological methods, we must take great care. How does the ancient understanding line up with modern understanding? If there is a discrepancy, is it clear where, why or when that may have occurred? And which do we trust? (For the past few decades, increasing numbers of scientific studies are being done on the practices of yoga. Check out Pure Action.) PERSONAL EXPERIENCE It may seem obvious to say, but all of these practices and traditions of yoga are intended to be put to use by actual living humans, like us. They only come to life when they are studied and executed. Those experiences we have and the inner knowledge we gain are hugely valuable, and one might argue that they are the central purpose of it all. On the other hand, the root of all the spiritual traditions is that our ordinary knowledge and perception are lacking and misleading. We must look deeper and strive to understand what is difficult and hidden. So, partly, our experience is the most important element, but it can also be the most misleading if we are not careful. TAKING THE THREE TOGETHER When assessing the methods and goals of yoga, we constantly weigh the contributions of these three elements: tradition, science and personal experience. There are some instances when all three align. This is the case with Alternate Nostril breathing, a practice described in the ancient texts, explained clearly with the modern scientific understanding of the nervous system, and reinforced by our own experience. We are quite confident in the function of this practice. Other practices are more difficult to justify. Inversions like Headstand and Shoulderstand were originally designed to prevent the falling of bindu from the head into the abdomen. Since that belief has fallen by the wayside, more modern practitioners try to ground the practices in physiological things like blood pressure or thyroid stimulation, which are questionable and unproven to the best of our knowledge. Yogic practices may be anywhere on this scale, swinging from 'traditional' to 'modern', and scientifically proven to completely debunked. Not to mention the experiences we have when we try these things for ourselves. We only suggest that you are considered and thoughtful when practicing yoga. Western medicine has known for decades (and yogis have known for thousands of years) that controlling the breath is a powerful tool to access the mind.

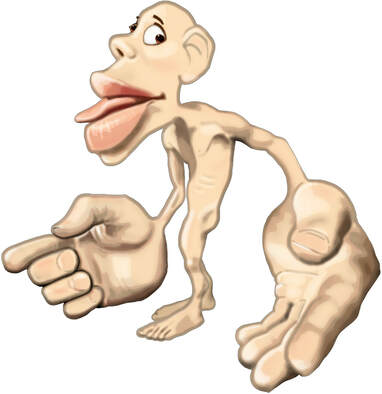

Now we know that this connection is largely via the autonomic nervous system. Every time we inhale, the heart rate goes up a little. And every time we exhale, the heart rate goes down a little. This is controlled by the two parts of the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic, respectively). In everyday life we tend to get overwhelmed with tasks and stress, which causes an overstimulation of our "active" nervous system. Our heart rate stays a little higher, we have trouble relaxing and we feel this as stress. In recent years breathing techniques have been making their way into the popular culture, with everything from heart rate variability monitoring devices to smartphone apps that help you control the breath. This includes a great new app called the "Breathing App" developed by yogi Eddie Stern and Deepak Chopra. The basis of their app is so-called "resonance" breathing, a specific, regular tempo that has benefits like lowering the blood pressure, improving heart rate variability and positive applications for anxiety and depression. The tempo is not difficult to achieve and is accessible for nearly every person. It ranges from breathing 5-7 times per minute as opposed to our normal rate that is closer to 15 times per minute. (5 times per minute is 12 seconds for a complete inhale & exhale. 7 times per minute is about 9 seconds for a complete inhale & exhale.) We recommend the "Breathing App." It is free and quite simple to use. It requires nothing more than a couple minutes of your time to breathe, regulating your inhale and exhale to achieve the coherence and resonance between the breath, heart and nervous system. Hopefully it will bring a little bit of peace, relaxation and well-being. A huge amount of the sensory and motor processing power of our brain is dedicated to the hands. It is necessary for us to function as we do in the world, picking up objects of various shapes and sizes, carrying things, judging their texture and temperature. But it means that at any given time, the brain has more of its attention focused on our hands than it does on, say, our back.

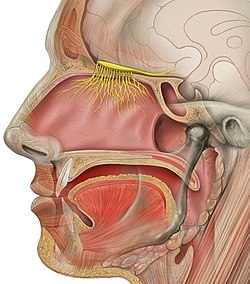

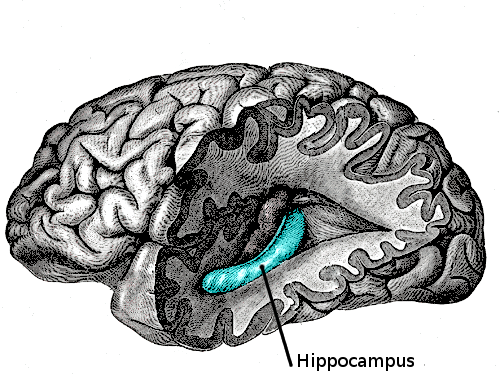

This function of your brain is represented by the picture above, called the Homunculus. It represents the amount of the brain's sensory power that is dedicated to each part of the body, with greater attention displayed by larger features. The results end up being almost obvious, with a lot of the brain's sensory attention focused on the lips and tongue, eyes and ears, genitals, hands and feet. These are the most sensitive parts of the body. What does this mean for us as yogis? In general, it means that it's easy for us to think about our hands. We may be doing an exercise that is focused on the spine, but we will wonder, "What do I do with my hands?" Or while we are balancing or breathing, "How should I hold my hands?" It is easy for our brains to answer this call, since it likes to put its attention on the hands. But this makes it harder to focus on things---parts of the body or mind---that are not the hands. It is difficult to take the attention away from the hands and put it on the spine or abdomen, or knees. Next time you do (or teach) a posture, check how much of your focus you put on the hands, their grip and their position. Then ask yourself if they are the central focus of the exercise. See if you can move your attention and effort away from the hands to the part that is most important for each practice. It can be challenging at first, but tremendously beneficial. Let's start with something obvious: we can breathe through either the nose or the mouth. The air that goes into our lungs is the same both ways, but there are vastly different effects on our nervous system and---according to new science---our brain. A new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience showed that "memory significantly increased during nasal respiration compared to mouth respiration."

But they also stated that "core cognitive functions are modulated by the respiratory cycle." Which means that our brain is hugely impacted by how we breathe.

Anyone who has practiced pranayama, which involves a lot of nasal breathing, has probably experienced its effects on the memory. It is almost ubiquitous that breathing practices bring up old memories and stimulate dreams of the past. Keep your eyes, ears and nose open for more news about this exciting branch of neuroscience! There are sure to be more developments as we understand the brain better. On our recent trip to India we visited Kaivalyadhama, the oldest yoga research facility in the world. It was founded by a yogi named Kuvalayananda, who dedicated his life to the three-fold mission of healing people through yoga, teaching the next generation of teachers and researching the scientific impact of the practices. The Kaivalyadhama campus now covers about 200 acres. It has grown from its humble beginnings as a small room for conducting research. As we walked the grounds, we were struck by a quotation from Kuvalayananda: "I have brought up this institute out of nothing. If it goes to nothing, I do not mind, but Yoga should not be diluted." It is a bold statement that shows clear values. Success---in terms of reach, money acquired or people reached---is not important. He goes so far as to say that he doesn't mind if the whole thing disappears!

What was vital to Kuvalayananda was the integrity of the teachings: "Yoga must not be diluted." It takes a strong vision and a strong will to carry out this mission, because it is far too easy to compromise our goals when survival or popularity enter the picture. This shows the intent of a yogi who's thoughts and actions are not swayed by worldly desires. Money comes and goes. Popularity comes and goes. Happiness comes and goes. Even our lives come and go. But knowledge and truth remain. We must not dilute knowledge for the sake of temporary things, even if our institutes go "to nothing". In our normal bodily positions like standing or sitting, the head is above the heart. Pumping the blood from the heart up to the head requires fighting the effects of gravity, so blood pressure in the head is higher than other parts of the body.

When we adjust the position of the body, as we often do in yoga practice, the head sometimes goes below the heart. When this happens, gravity pulls blood into the head, raising the blood pressure. Our body adjusts by decreasing the blood pressure in the head to protect the brain and face. This effect can be both positive and negative depending on our health and our bodies' ability to adjust the pressure. If we are healthy, the shifting of the blood pressure up and down can be beneficial, teaching our systems how to respond to changing conditions. This is why healthy people should put the head below the heart. If we have high blood pressure we must be very careful. Whenever the head goes below the heart, it is possible that the blood pressure will get dangerously high before the body responds. Or the body may not respond effectively and let the blood pressure stay too high for too long. So those of us with high blood pressure should take care when putting the head below the heart. We can do gentle "inversions" by bringing the head even with the heart or only slightly below. This can be done in forward folding positions and kneeling positions like Half Tortoise or Child's Pose. Our feet are where the body contacts the floor/earth. Every ounce of our body's weight goes through them with each step, whether we have a light step or plod heavily. So they are vitally important to our physical health. Poorly functioning feet lead to a poorly functioning body much the same way that damaged wheels make a poorly functioning car.

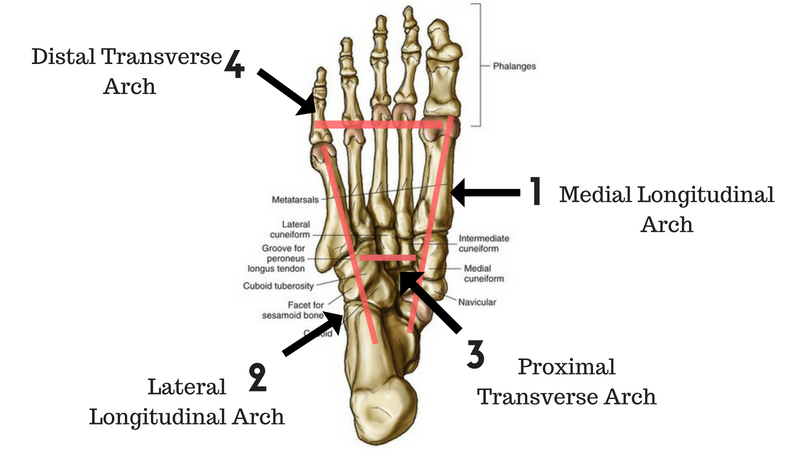

We have all heard of "flat feet," where the inside arch of the foot collapses toward the floor, often creating painful repercussions in the ankle, knee, hip and even back. This condition commonly refers to just one of the arches of the foot---of which there are four---the medial longitudinal arch (labeled above, #1). That is a fancy way of saying the lengthwise (longitudinal) arch on the inside (medial) of the foot. Most of us just know it as the "arch." This well-known arch of the foot is not structured like a weight-bearing arch. It is built more like a spring that bends when we put weight on it and bounces back as we release. This is how some of the "spring in our step" occurs, as the arch recoils. This arch can be bolstered with muscular strength, like lifting the inner ankles up and pulling the ball of the foot toward the heel. The second major arch of the foot is the lateral longitudinal arch, which means the lengthwise (longitudinal) arch on the outside (lateral) of the foot. It is labeled in the picture above with #2. This arch goes from the heel area toward the pinky toe. It is a very stable arch, with bone structure like a traditional weight-bearing arch. Due to its structure, this arch rarely collapses or gives us trouble, so we don't even realize it's there. The third arch of the foot goes across the foot, so it is called a transverse arch. Since it is closer to the ankle, it is called the proximal (near to the body) transverse arch, labeled #3 in the picture above. This arch, like #2 above, is structurally very stable and rarely collapses or gives us trouble. This arch is also called the anterior (forward) transverse arch. The fourth arch of the foot is sometimes not considered an arch at all because it is not formed by arch-like bony structures. Instead, this arch is made of soft tissues like ligaments, muscles and fascia, stretching from the big toe to the baby toe. It is called the distal (far from the body) transverse arch, labeled #4 in the picture above. Since it is not a bony-structured arch, this often gives us trouble due to weakness and under-use, especially since we wear shoes that decrease our body's need to access it. It can be strengthened though simple exercises like making fists with the toes. Try standing with bare feet. Shift your weight around your feet, from front to back and side to side. Pay close attention and see if you can feel the arches and structures in your feet. They are important! It has become popular in the sport, fitness and yoga worlds to drink alkaline water, water with a pH higher than regular water and higher than our blood. Some use alkalizing filters for their home or studio, while others buy alkaline water straight from the store in bottles.

The supposed benefits of drinking alkaline water range from better hydration and improving acid reflux to curing headaches and even cancer. But, according to a recent New York Times article, "there is no science to back it up." "Despite the claims, there’s no evidence that water marketed as alkaline is better for your health than tap water," the article says. There are two elements to look at here. The first is whether drinking alkaline water actually changes the pH of the body, and the second is whether a change in pH will provide benefits. The answer to both of these queries seems to be no. "Blood is tightly regulated at around pH 7.4." Our stomach secretes hydrochloric acid to digest our food and kill germs, and this acidic environment "quickly neutralizes" any alkaline substance before it makes its way into the rest of our digestive system or blood. So drinking water that is slightly alkaline won't affect the pH of our blood or body. Also, there no evidence that alkaline water provides health benefits. To the contrary, there are known risks including impaired growth and damage to cardiac muscle. "The only health effects that we know of are danger signs, so for people to continue to market alkaline water — they’re really as bad as the snake oil salesmen of yesteryear." We hope you stay hydrated, but you probably only need to drink regular water! Excerpts from: Is Alkaline Water Really Better for You? in the New York Times |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed