|

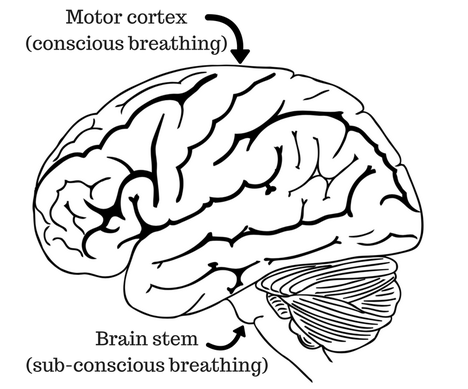

Most of us know that our breath functions automatically most of the time. This function---breathing without thinking---is controlled by the autonomic nervous system in one of the oldest parts of our brain: the brain stem, located at the base, where the spinal chord turns into the brain.

Most of us also know that we can control our breath consciously, choosing the speed at which we breathe and even stopping it altogether, for a short while at least. This conscious control of our breath is done by the somatic nervous system, the part that controls voluntary functions like walking, writing or playing baseball. It is located on the surface of the brain at the very back of the frontal lobe, in a place called the motor cortex. Whenever we consciously control our breathing, the motor cortex overrides the brain stem. This process takes a lot of effort from the brain, which is why it has the effect of focusing us. As an experiment, try to control your breath while doing a math problem in your head. It is difficult. When we consciously control the breath, the brain becomes still. This phenomenon is one of the key principles of pranayama (breath control) and even the most simple breathing exercises. Even for a true beginner, counting the breath or trying to control it at all calms the mind and leaves them feeling very focused.

1 Comment

Uddiyana and Nauli are traditional yogic practices. They date back more than 500 years to at least the Hatha Pradipika.

To do Uddiyana, one holds the breath out and then expands the ribcage as if inhaling. What results is a vacuum in the abdomen which sucks the belly, intestines and organs up. Uddiyana means 'flying up.' "This practice is called Uddiyana because the diaphragm is made to fly up from its original position and held very high in the thoracic cavity." (Yoga Mimamsa, Vol. 1, Oct. 1924) In the early 1920s, Swami Kuvalayananda began a school and laboratory, using modern scientific equipment to test traditional yogic practices and publish the results. His newsletter is Yoga Mimamsa, which started in 1924 and continues today. The first edition was dedicated to the study of Uddiyana. They performed two ground-breaking studies, one involving early X-Ray technology to view the intestines, and the other measuring the internal pressure of the abdominal cavity during Uddiyana. "This exercise has been studied under the X-Ray. Very interesting and valuable data have been collected. Two X-Ray experiments are published...and an article discussing the therapeutic value of this Yogic practice is included..." (ibid.) The pictures above are from the 1960s, when Dr. Gouri Shankar Mukerji performed a similar experiment. These pictures are much clearer than the ones from 1924, which is why we post them here. The x-rays from 1924 are cloudy and difficult to discern. In the above pictures, one can clearly see that Uddiyana pulls the intestines and organs up into the thoracic cavity. The second test measured pressure in the intestines and rectum during the practice. They found that internal pressure is reduced, creating a partial vacuum. "As soon as the muscles were moved for Nauli, the mercury fell through 40 mm. indicating a clear partial vacuum." (ibid.) The discovery of this vacuum was significant, since scientists of the time hypothesized that Nauli reversed the peristaltic movement of the intestines, which would be detrimental to health. The discovery of the partial vacuum refuted this idea. Kulvalayananda named his discovery the "Madhavadasa Vacuum," after his esteemed teacher. This week I picked up Time Magazine's "The Science of Exercise" special issue, as it promised to illuminate the most recent discoveries in movement and health. It is interesting to think about what this means for the future of yoga practice. I recognize that yoga is traditionally not an exercise regime, but it has become quite physical over the past 100 years, to the point that it now fills the fitness quota in many people's lives.

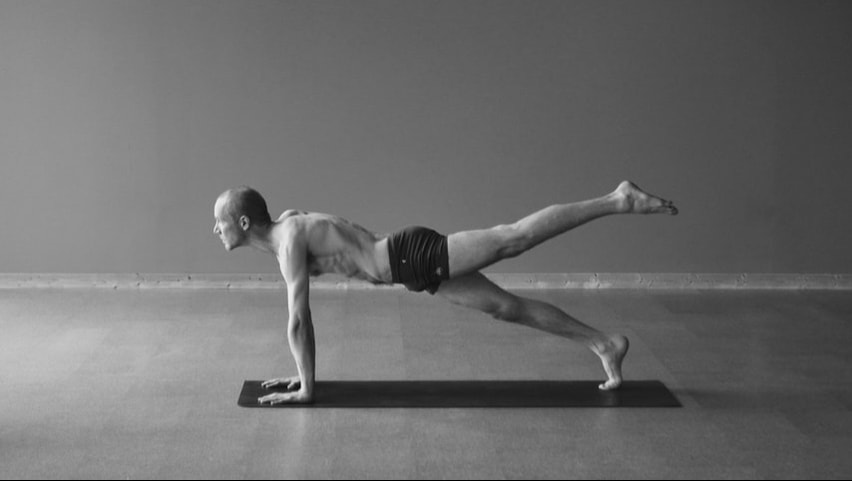

Exercise Will Become More Individualized and Prescriptive As the medical community recognizes the preventive value of exercise, it will be recommended more to patients of all ages, both to combat disease and to prevent it. Physical activity reduces the risk of heart disease, many forms of cancer and several mental disorders like depression. In the future, each person will be assigned or "prescribed" a different exercise regime based on their health, ability and needs. This is not unlike the method of prescriptive yoga that has been in India for hundreds of years. "Young and old," wrote Bishnu Ghosh in 1930, "there is a different exercise for each of you--an experienced trainer can only rightly select them." Lifting Weights Is Important For Strength and Health Muscular strength and bone density are two important factors in keeping us healthy and pain-free. Weak muscles lead to imbalance, injury and painful joints. Keeping our bodies strong, especially around the spine, hips, knees and shoulders reduces the risk of injury as we age. Keeping the bones strong is also important, reducing the likelihood of breaks. Both of these things are improved by lifting weights. Thus, weightlifting should be a regular activity for pretty much everyone. Yoga exercises increase strength to a certain degree, using the bodyweight as resistance. More often, though, yoga practices are focused on flexibility at the expense of stability and strength. Our overall health will be better served if we focus at least part of our physical practice on strength. Flexibility is useful when it restores functional range of motion to stiff joints, but it can also be detrimental when pushed too far. A balanced practice of flexibility and strength, even including weight lifting, will be more effective in keeping us healthy in the long term. Our recent blog about the myth of oxygenation got a big response. Lots of surprise, some disbelief and a lot of requests for more information. Specifically, if deep breathing does not have a positive impact on our oxygen levels, why do we do it?

There are three huge benefits to practices of breathing: activating and balancing the muscles of breathing, which in turn affects the nervous system; balancing the hemispheres of the brain through the nostrils; and awareness and minor control of the breath-regulating parts of the brain. THE MUSCLES & THE NERVOUS SYSTEM You may have heard that some people are belly breathers and some are chest breathers. Most of us have at least a slight imbalance between the abdomen and chest, while others have extreme imbalance. This doesn’t necessarily have an effect on our ability to get oxygen, but it does have an impact on our nervous system. Generally speaking, abdominal breathing that uses the diaphragm and relaxes the abdominal muscles stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system. The opposite is true for chest breathing that uses the intercostal muscles. This stimulates the sympathetic nervous system. Neither of these is a problem until our breathing patterns become imbalanced and we breathe primarily through only one of the systems. When years or decades go by, one part of the nervous system chronically gets stimulated while the other gets suppressed. Belly breathers will be more relaxed, sleep more, have lower body temperature, be more lethargic. Chest breathers will be more energetic, more stressed, warmer, sleep less. It is vital for progress in yoga to have balance in the nervous systems. So the first step of breathing practice is to learn to use both parts of the breath, strengthening the muscles and evening the nervous systems. BRAIN HEMISPHERES The olfactory nerves in the nose go straight to the brain. They have the most direct connection to the brain of any of the senses, so their stimulation through the nostrils is potent. The breathing practice of Alternate Nostril, which goes by many names, is one of the oldest yogic techniques. By alternating which nostril we breathe into, we vary the hemisphere of the brain that we stimulate. This has a further effect on the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and goes even further to balancing the dual nature of the body and mind. PARTS OF THE BRAIN The breath is controlled by the brain stem, the oldest part of our brain. Most of the time, we breathe with no conscious thought. But the newer parts of the brain, specifically the cortex, have the ability to override the brain stem to some extent, especially with practice. This awareness and control is very difficult and not appropriate for beginning practitioners, but it is the ultimate reason for breathing practices. Gradually we come to realize the true nature of the breath, which brings us closer to realizing the true nature of the self. (Apologies for the abstract yogi talk, but I don’t know of a clearer way to put it.) IN CONCLUSION So breathing is powerful. If we use it correctly it has the ability to balance our nervous system, the hemispheres of the brain, and even put us in touch with some deep and essential parts of our being. To me, this is all way more exciting than oxygenating the body!! How many times have you heard a yoga teacher tell you that deep breathing "oxygenates the blood?"

It isn't true. At the very least it is misleading. Our nervous system forces us to breathe at the necessary rate to fully oxygenate our blood at all times. This is true when we're resting as well as when we're running a marathon. The body's oxygen requirements are different depending on our activity, and the nervous system automatically adjusts to oxygenate the blood fully. Normal blood oxygenation is 95-100%. When we are at rest, we breathe slower since the body's oxygen demands are less. Breathing more or deeper while the body is at rest does not "oxygenate" the blood. It hyper-ventilates, which is just a way of saying breathing (ventilating) more than necessary. Anytime we breathe more than the body requires, the big change we are causing is the removal of carbon dioxide, one of the body's metabolic wastes. Hyperventilation removes more carbon dioxide than the body produces, and this leads to a whole host of physiological effects. Most significantly, the blood vessels in the brain constrict, limiting blood flow to the brain. This makes us light-headed. So that light-headed feeling you get when breathing deeply isn't energization or "oxygenation," but constricted blood vessels in the brain. Your brain is actually getting less oxygen than if you were to breathe normally! A study in Finland checked the frequency of sauna usage against the rate of hypertension, or high blood pressure, by following more than 1,500 middle aged men for an average of 25 years. The New York Times wrote about it a couple days ago.

The study found that, when compared to subjects who used the sauna only once per week, those who used it 2 or 3 times were 24% less likely to have high blood pressure. Those who used it 4-7 times were 46% less likely. "The warmth of the sauna...improves the flexibility of the blood vessels which eases blood flow, and the warmth and subsequent cooling down of a typical Finnish sauna induces a general relaxation that is helpful in moderating blood pressure. Also, sweating removes excess fluid, acting as a natural diuretic. Diuretics are among the oldest drugs used to treat hypertension." (NY Times) The New York Times just reposted an interview with exercise physiologist Dr. Oliver Jay, asking if there are health benefits associated with sweating, and if more sweat means more benefit. This is a question that hits home to us as yogis who strive to build inner heat, and especially as part of the Bikram and Hot yoga communities where lots of extra heat is added for supposed increased benefits.

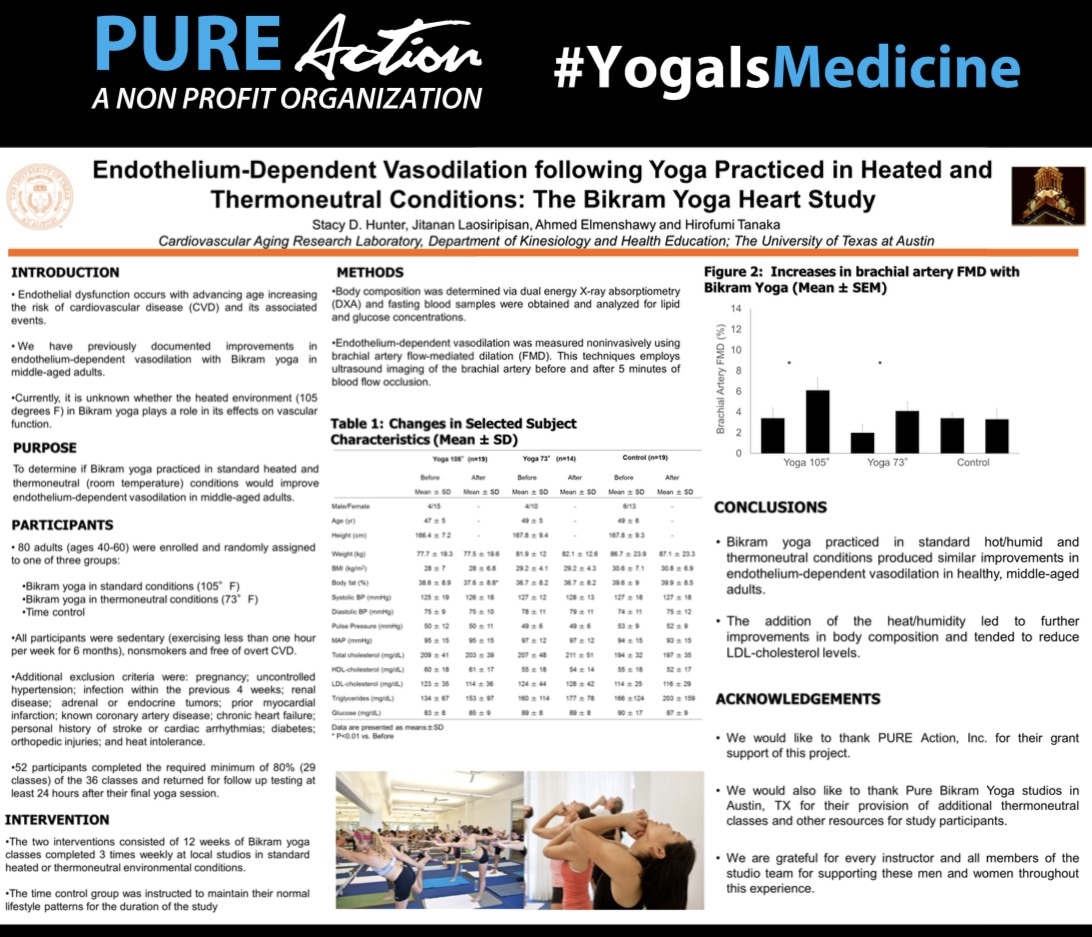

“There’s this entrenched idea that it’s good to ‘sweat things out,’” Dr. Jay said, but in fact “sweating, per se, provides no health benefits,” apart from preventing overheating. Exercise, especially vigorous exercise, raises the internal body temperature. "The benefits derive from the exercise itself," not the accompanying rise in body temperature or the sweat that is meant to cool us. Perspiring, in and of itself, does not provide or amplify those effects, Dr. Jay said. That situation doesn’t change if you’re sweating due to a hot environment. “Sweat is sweat,” he said. You will perspire more if the air is humid, he said, because sweat doesn’t evaporate efficiently in humidity, and it’s evaporation that actually cools your body. But you aren’t gaining extra health benefits from drenching your clothing with perspiration. CONSIDERING "HOT" YOGA We got our start in Bikram's class, where the temperature is 105 degrees and you sweat like crazy. There is a continuing trend toward making yoga hot to induce more sweating and increase muscle flexibility (which largely happens through numbing the nervous system, but that's another story). Also there is the "sauna therapy" argument, that when exposed to high temperatures the heart rate increases and the blood vessels dilate, improving cardiac and vascular function. There is new research that practicing yoga in high heat may have a positive impact on cholesterol levels. Contrarily, there is new research that many of the vascular benefits of yoga and stretching are gained at room temperature just as well as in a heated room. CONCLUSION? There are 3 main arguments for practicing yoga or exercising in the heat: 1) increased effectiveness of the exercise, as indicated by rise in body temperature and amount of sweat; 2) increased mobility and flexibility; and 3) benefits to the cardiac and especially vascular system. Argument #1 is simply not true. An exercise is not more beneficial when done in heat, and more sweat - even higher body temperature - does not mean more benefit (see the NY Times article). Argument #2 is a double-edged sword. Heat-induced flexibility may be beneficial to certain parts of the population, like the elderly or injured, but it is detrimental to those who are already flexible, encouraging hyper-mobility. For the general public it's a toss-up. Argument #3 is a good one, and it's gaining clarity with each passing study. Pure Action is funding research to try to tease out the vascular benefits that may come from heat without yoga, those that may come from yoga without heat, and those that are accentuated when the two are put together. Anytime we use the body, it helps to know how it works. What are the results of our actions in the skeleton, muscles, tissues, organs and nervous system? This is especially important if we want the physical practice to build our health and avoid injury.

A lot of therapeutic yoga also uses knowledge about digestion, organ function, blood pressure and chemistry of the body. These things don't technically qualify as anatomy but lie more in the functional sciences. Yogic practices of Pranayama (breath control) have a profound impact on the autonomic nervous system and the blood acidity, which in turn has diverse effects through the body and mind. Even Meditation is being illuminated by modern science, as we develop machines that take pictures of our brain function and how it is effected by various mental practices. So many results of the yoga exercises can be explained and clarified by modern science, making it easier to understand, easier to duplicate and a lot easier to teach to others. The results are in from a new study called the "Bikram Yoga Heart Study." It tested a variety of factors like blood glucose and vascular health as the subjects practiced the 26+2 of Bikram yoga. Some subjects practiced in 105 degrees (F) while others practiced at room temperature, 73 degrees.

"Results showed significant and equal improvement in brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (an index of vascular health and heart disease risk) with 12 weeks of both the heated (105-degree) yoga and non-heated (73-degree) yoga groups. However, while both yoga practices were equally beneficial on the vasculature, there were some differences in their effects on other variables with additional reductions in body fat percentage and a trend (almost statistically significant) toward a reduction in LDL (bad)-cholesterol being seen only in the hot yoga group alone." This study was funded by Pure Action. One of the oldest practices of Hatha Yoga is Alternate Nostril Breathing. It is often named Nadi Shodana, which means "purifying the channels", and its instruction dates back as many as a thousand years to the Yoga Yajnavalkya. It is arguably the most powerful breathing practice known in yoga. Modern medicine's understanding of the nasal cycle and an exciting new study uncover new meaning in this ancient practice. NASAL CYCLE Have you ever noticed that sometimes your right nostril seems clogged, and other times the left side does? Our bodies have a natural cycle called the nasal cycle that alternates breathing through each nostril. This helps balance the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems and the body's temperature, as well as helping us smell and humidify the air we breathe. Sometimes we have a dominant nostril, usually because of congenital or accidental blockage of one of the nostrils, so our breathing might be dominated by one side. Studies have shown a correlation between nostril dominance and hemispheric dominance of the brain, meaning that one side of the brain is being stimulated more than the other. Also, it means that one part of the nervous system is being stimulated more than the other. When we alternate our breathing from one nostril to the other, we encourage balanced stimulation our autonomic nervous system, help regulate the temperature, stress and alertness of our bodies, and even out imbalances that may have developed over years. DR. BALASUBRAMANIAN A recent study by Dr. B (full name above) shows another exciting aspect of this ancient practice. The subjects in his study chanted and did Alternate Nostril Breathing for 10 minutes. They showed an increase in nerve growth factor (NGF) in their saliva, a chemical that our brain uses to build and repair connections. The reduction of NGF has been linked to Alzheimer's Disease, so it is possible that breathing practices such as Alternate Nostril may lower the risk of Alzheimer's. You can watch Dr. B talk about his study in the video below or read about it here. More research needs to be done, but it is exciting stuff. PURE ACTION Dr. B's study was funded by Pure Action, an organization in Austin, TX that supports many studies about yoga. They are bridging the gap between the ancient lore of yoga practice and modern medical science, something we think is vitally important to the health and growth of the yoga community. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed