|

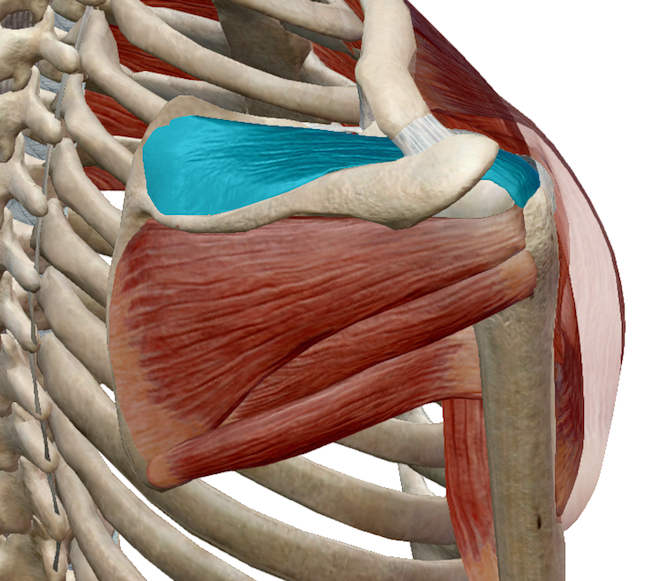

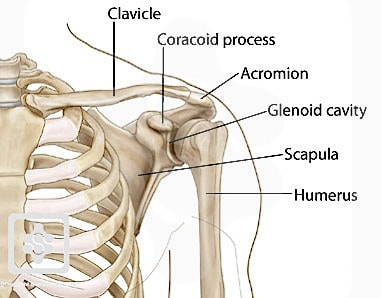

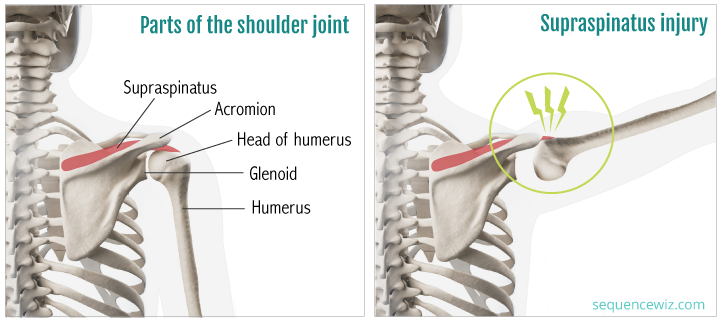

This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. Two common injuries in yoga happen in the shoulder. One is in the front of the shoulder---the biceps tendon---which we will address next time. The other is in the top of the shoulder, called impingement. It happens when the arm lifts up high; the arm bone can bump against the edge of the shoulder blade, called the acromion, and damage the tendon there.

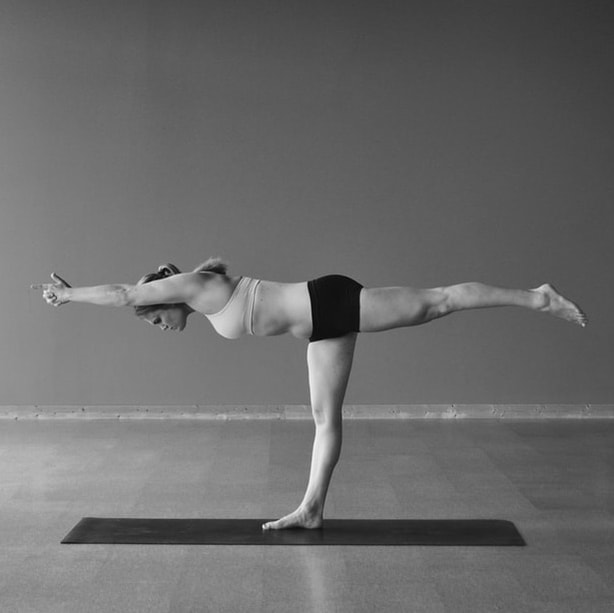

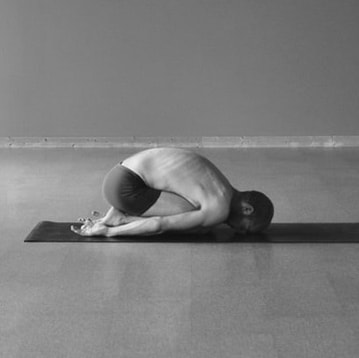

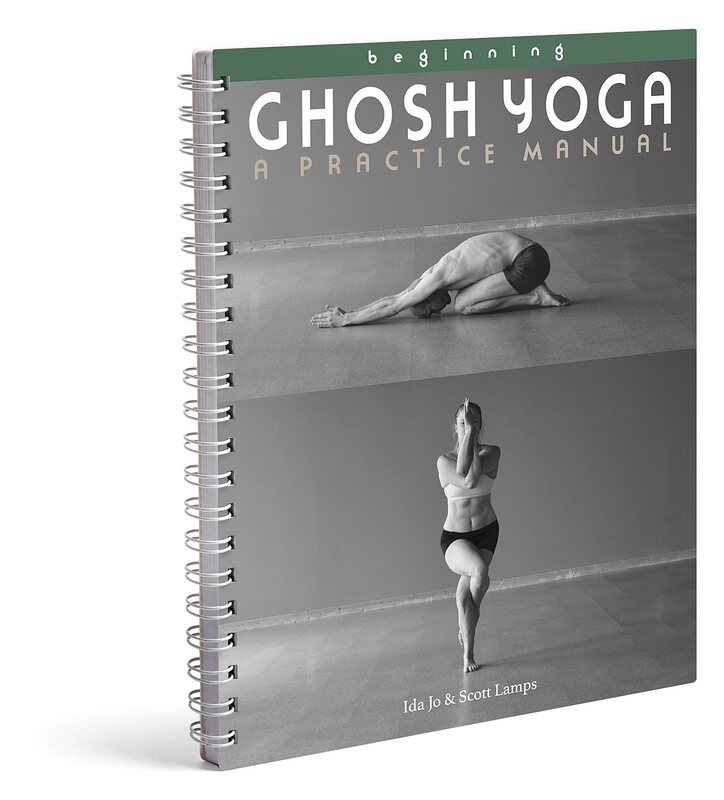

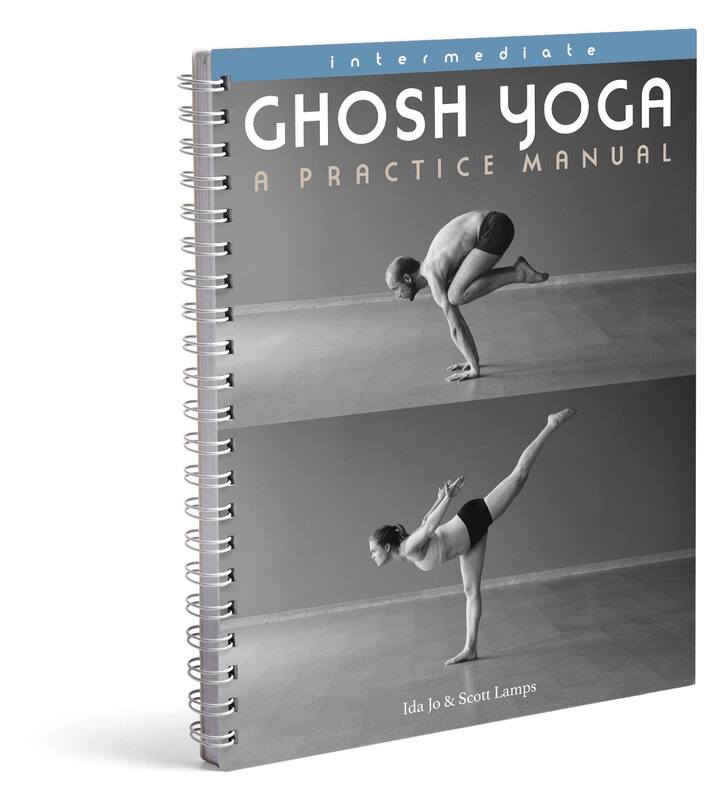

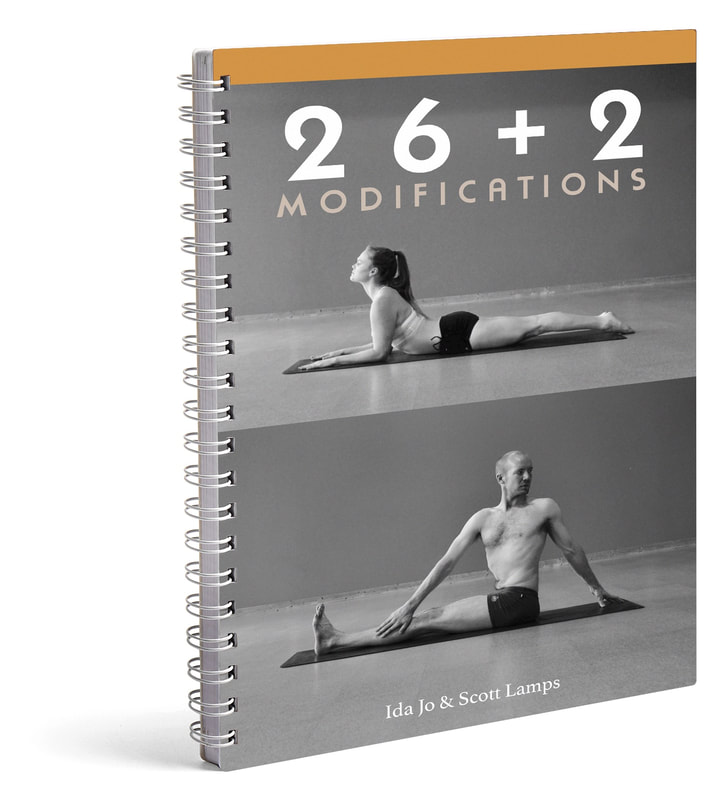

HOW THIS CAN HAPPEN In yoga, this happens most often when we force the arms overhead. Think of any time you link your hands together and then try to straighten your arms using force. As pictured below, it happens in Half Moon Backbend, Half Moon Sidebend, Balancing Stick and Half Tortoise, among others. (It also happens in Downward Facing Dog.) When we force our arms to straighten overhead, we usually use the triceps, a muscle mainly of the elbow, to compel movement in the shoulder. This is where we get into trouble and impingement can happen. You will feel a 'pinching' sensation in the top and outside of your shoulder. This is the bones bumping into each other, damaging the soft tissue. If the shoulders become injured this way, they will be painful whenever lifting the arms sideways, and the breathing exercise pictured at the top will cause pain.  HOW TO HELP The simplest and most effective way to avoid this injury is to not link your hands together. Just place them side by side without interlacing the fingers. Interlacing the fingers and forcing the arms straight overhead is the easiest way to create the injury. Or don't lift your arms overhead (pictured below left). Most postures can be done quite effectively without the arms overhead. All of the positions pictured above don't require the arms to get the primary benefit. Alternatively, you can lift your arms forward and up (pictured below) instead of out to the side. This will help the shoulder blades move into the proper position and keep the shoulders healthy. In the breathing exercise, pictured at the top, you can keep your elbows lower, not lifting them higher than the shoulders. This will prevent further irritation of this area. To build strength in the area, postures like Full Locust will help (pictured below right). By pulling the shoulders back and together, we build strength in the back of the shoulder to help stabilize and balance the joint. CONCLUSION

The moral of the story is that we should be aware and careful when lifting the arms overhead, especially if we are gripping the hands together and straightening with force. If there is a 'pinching' sensation in the top of the shoulder, back off immediately. There is nothing there to 'stretch', and it is likely that we are impinging our supraspinatus tendon. Try adjusting your approach to the posture and using your shoulders a little differently. Happy, healthy practicing.

8 Comments

As teachers, we are in service of the transmission of knowledge. Our goal is to acquire knowledge in order to pass it on to our students. When our students gain that knowledge and can hold it on their own, we have succeeded.

As we go through this process of acquiring knowledge and passing it on, we must remember that knowledge itself is not ours. Once we learn something, we do not own it. It is not ours to hold onto at the expense of others. We are in service of knowledge. Knowledge is not in service of us. Our ego doesn't always like the process of teaching. The ego easily jumps in and says, "Wait! I'm the teacher, I'm in charge. This is my class, my system, my teachings." While this might not be conscious or obvious, we might notice it as twinges of self doubt, or fear that we will become less valuable if our students advance too far. This becomes an inner battle for teachers, one that needs to be handled with great care. We must remember our very job is to give to our students. When our students understand what we've taught them and hold that same knowledge, we must celebrate this. This is what it means to teach. It can be difficult to know what is real in this world. The methods of yoga, spirituality and science have developed to explore this question. Sometimes they come to the same answers, but sometimes they contradict.

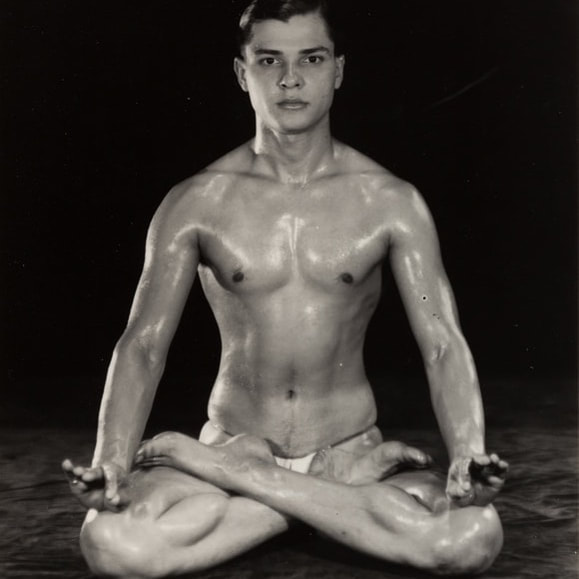

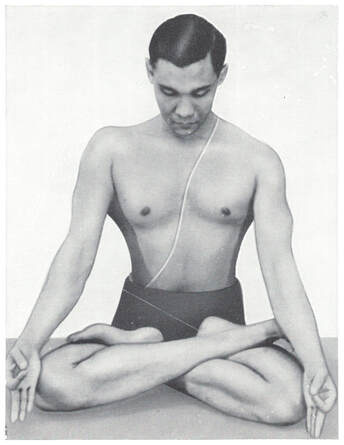

As yoga teachers, we are often confronted with the problems of: 'Why do we do these things?' and 'What is right?' We usually look in three places to find answers: tradition, science and personal experience. TRADITION We at Ghosh Yoga are fascinated with tradition, and we have researched it, studied it, lectured on it and challenged it. We have written about the relationship of oldness and tradition, the Spirit of Tradition, and the sometimes misleading value of tradition. With regards to these questions---what is real? and what is worth learning?---tradition plays an important role in yoga. Many of us are drawn to yoga because of its ancientness, sacredness and gravity. And the idea of lineage, teaching in the same way as you were taught, is a time-worn Indian method that has come to the West with yoga. At its best, a lineage links modern students with ancient teachers and sages. We must take these things seriously. What did our teachers think and what did they teach?If we look in older texts, what was being taught hundreds or thousands of years ago? Most importantly, how do these apply to modernity? Can we extrapolate our own situations, thoughts and perspectives from ancient teachings? SCIENCE In the past few centuries, scientific methods have developed that are centered around the reliability and repeatability outcomes. The sciences have improved our understanding of anatomy, physiology, biomechanics and neurology among other things. We can apply this knowledge to the body and mind in yoga practice. But it can sometimes come into conflict with traditional understanding. For example, humans did not know the intricacies of bodily anatomy until the 15th century CE. This is clearly depicted in art from earlier, where the body is only really understood by looking from the outside. Take this one step further inward, to the functioning of breathing, energy or the nervous system. These things have come into focus even more recently in human history. Therefore, when we look to 'tradition' for physical, anatomical or physiological methods, we must take great care. How does the ancient understanding line up with modern understanding? If there is a discrepancy, is it clear where, why or when that may have occurred? And which do we trust? (For the past few decades, increasing numbers of scientific studies are being done on the practices of yoga. Check out Pure Action.) PERSONAL EXPERIENCE It may seem obvious to say, but all of these practices and traditions of yoga are intended to be put to use by actual living humans, like us. They only come to life when they are studied and executed. Those experiences we have and the inner knowledge we gain are hugely valuable, and one might argue that they are the central purpose of it all. On the other hand, the root of all the spiritual traditions is that our ordinary knowledge and perception are lacking and misleading. We must look deeper and strive to understand what is difficult and hidden. So, partly, our experience is the most important element, but it can also be the most misleading if we are not careful. TAKING THE THREE TOGETHER When assessing the methods and goals of yoga, we constantly weigh the contributions of these three elements: tradition, science and personal experience. There are some instances when all three align. This is the case with Alternate Nostril breathing, a practice described in the ancient texts, explained clearly with the modern scientific understanding of the nervous system, and reinforced by our own experience. We are quite confident in the function of this practice. Other practices are more difficult to justify. Inversions like Headstand and Shoulderstand were originally designed to prevent the falling of bindu from the head into the abdomen. Since that belief has fallen by the wayside, more modern practitioners try to ground the practices in physiological things like blood pressure or thyroid stimulation, which are questionable and unproven to the best of our knowledge. Yogic practices may be anywhere on this scale, swinging from 'traditional' to 'modern', and scientifically proven to completely debunked. Not to mention the experiences we have when we try these things for ourselves. We only suggest that you are considered and thoughtful when practicing yoga. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed