|

Gosh I love to read! Every book is an opportunity to see the world from a new perspective, to learn something from an expert, or to peer through a window to a different time and place. Here is a short list of books I read this year that had a profound impact on me. They are not new books. In fact, some of them are quite old. But they are all valid, and they meant a lot to me this year. WHEN PROPHECY FAILS by Festinger, Riecken and Schachter This work of social psychology from the 1950s dives into the mentality, actions and beliefs of a UFO cult. But it is so much more than that: an exploration of how our minds react when we may be wrong about something we really believe in. The authors build the case that, even when we are confronted with evidence that we are wrong, we essentially double-down in our beliefs. It is a chilling conclusion — that humans are sometimes immune to changing our minds. As the authors write, "when people are committed to a belief and a course of action, clear disconfirming evidence may simply result in deepened conviction". After reading this book, it is hard not to see this phenomenon all around us in the world today. ETHICS IN THE REAL WORLD by Peter Singer Ethics and morality have become especially important to me this year. Perhaps it is due to the ongoing pandemic and the acute awareness of how my actions can impact others. I stumbled upon this book, which contains 82 short essays about various ethical conundrums — from geopolitics to religious freedom, eating meat to climate change — and thought it would be a good overarching introduction. It is. Singer writes with remarkable clarity about ethical issues of all sorts. And the brevity of the essays means that nothing is belabored. SELFLESS PERSONS by Steven Collins This scholarly dive into the Buddhist concept of non-self is deep, complex and absolutely stunning. The idea that there is no eternal Self can be confounding and frustrating, especially when compared to other systems that insist upon its existence. The importance of non-self is summarized best in Collins's introduction: "this belief in a permanent and a divine soul is the most dangerous and pernicious of all errors, the most deceitful of illusions, that it will inevitably mislead its victim into the deepest pit of sorrow and suffering". SEVEN TYPES OF ATHEISM by John Gray I'm a sucker for an analysis of human spirituality in all its subtlety, diversity and contradiction. Gray's book does not disappoint. He begins by defining an atheist: "anyone with no use for the idea of a divine mind that has fashioned the world...It is simply the absence of the idea of a creator-god". This leaves a lot of room for variation in beliefs about the nature of the universe, creation and human spirituality. Gray systematically explains seven distinct forms of atheism that have been embraced throughout history. A book of remarkable clarity and exposition that illuminates the ways we see ourselves and the world. THE YOGASUTRA OF PATANJALI: A NEW INTRODUCTION TO THE BUDDHIST ROOTS OF THE YOGA SYSTEM by Pradeep P. Gokhale I don't know how many different translations and explanations of the Yoga Sutras I have read. Dozens. Many are confused or confusing, and scholars are increasingly aware of the compiled nature of the text, and how it shows influence from a handful of other systems of thought. Buddhism is among these influences, but deep dives into the Buddhist roots of the Yoga Sutras require a rare combination of expertise. With this new research, Gokhale has provided a huge step forward in our understanding of the philosophical and linguistic roots of the Yoga Sutras. He analyzes works of Abhidharma Buddhism and shows how they explain many aspects of the Yoga Sutras better than traditionally accepted narratives. This is a scholarly work, full of difficult history and terminology, but worth it for anyone with a serious interest in yoga history or the Yoga Sutras in particular. WHY WE SLEEP by Matthew Walker This book was recommended to us by several people over the past few years until it became impossible to ignore. And it was worth it! We even wrote a blog about it. The book begins with the obvious-in-hindsight revelation that sleep is vital. It is not a passive state of nothingness that can be shortened or neglected. Rather, it is a very active state for many systems of the body, especially the brain. Walker explains the structure of sleep and its impact on things like our memory, physical health and even physical coordination. This is a book with practical, everyday implications that can make anyone's life better. THE CHAKRAS by C.W. Leadbeater Earlier this year, as we were doing research for a workshop series on the Yogic Body, we read a handful of books about the chakras from the early 20th century, including this one. Leadbeater was a prominent Theosophist, a highly influential group that shaped modern conceptions of yoga and spirituality. This book from 1927 is remarkable as a vivid capsule of the time. Leadbeater claimed that he could see the chakras, and he painted them beautifully. I find these paintings to be among the most remarkable elements of 20th century yogic history because, aside from being lovely, they show the break-neck speed of change in conceptions of the yogic body. Here, in the 1920s, there were seven chakras associated with parts of anatomy. But they were not yet rainbow in color nor linked with psychological traits as they came to be in the 1970s. HOW JESUS BECAME GOD by Bart D. Ehrman Along with our study of yoga history and the history of religion in general, both Ida and I have been increasingly reading about the history of Christianity. It is fascinating for the same reason as all history — our ideas change rapidly along with the cultural needs of the time. This book by Ehrman explores the early centuries after the death of Jesus, and how the story of Jesus changed, turning him from a preacher or even a prophet into the only son of God himself who rose from the dead. It is full of scriptural quotations and explanations alongside historical analysis. And it is quite readable, which is not something one can often say about a work of scholarship like this. BREATH by James Nestor

I never thought someone could write a compelling story about breathing, something we all do thousands of times each day. But Nestor has crafted a surprisingly interesting narrative around his own research into breathing anatomy, physiology and history. Where it falls short of a scholarly history or a medical anatomy text, it more than makes up with its humor and readability. This is a book that anyone can and should read to have more understanding and appreciation of the most fundamental function of life — breathing.

0 Comments

Navigating the yoga world can be frustrating. There are so many different styles and so much history underpinning the practices. Not everyone thinks that yoga's history is important, but many find value in the traditions. If you are someone who cares about — or wants to care about — yoga's history and traditions, here are four important concepts, explained as simply as we can.

VEDA The word Veda (pronounced vay-duh) means 'knowledge'. This is the name given to the sacred scriptures of Brahmanism/Hinduism. Sometimes these traditions (like Hinduism) are even called Vedic religions because they are largely defined by their reverence for these holy books. The Veda is considered to be revealed knowledge, meaning that it was not written or composed by a human. It was simply written down by humans, sages with special abilities of sight. The knowledge within is thought to be universal, eternal wisdom, something akin to 'the word of God'. UPANISHAD The Upanishads are the last group of books in the Veda. It can help to think of them like the New Testament of the Christian Bible. They are grouped with the rest of the Veda as revealed knowledge, but they present a somewhat different view of the world and spiritual effort. The Upanishads introduce an internal spiritual path, where rituals are carried out in one's own heart rather than externally. This is also where the concept of 'yoga' is introduced, an inward linking of one's awareness to the infinite consciousness within. YOGA Yoga means 'linking' or 'harnessing'. In the Upanishads, where the concept of a spiritual practice named 'yoga' first arises, it refers to linking our awareness within rather than to the world outside. At other times, in more God focused traditions, yoga can refer to linking one's awareness or being with God. In medieval systems of hathayoga, abstract concepts of non-duality became common. Much like the concept of yin and yang, where two opposing forces combine to create balance, yoga could mean the balance of male-female, sun-moon, hot-cold, etc. In this way, many people now define yoga as 'union', which usually refers to some sort of balance or non-duality. In the modern West, most will relate yoga to a physical routine of stretching and relaxation. This type of yoga is pretty new, about a hundred years old. HATHA Hathayoga developed about a thousand years ago. It was a method of using the body to force an effect on consciousness. This is probably why it was called hatha, which means 'force'. A more poetic explanation of hatha developed a little later: it is the union of masculine (ha) and feminine (tha). Much like 'yoga', above, this understanding appeals to balance and unity. In the last couple hundred years, hathayoga has taken on the meaning of 'any physical practices, like postures or breathing'. As such, a lot of modern yoga refers to itself as hathayoga. But modern yoga is a pretty new phenomenon, quite different in practice and belief from the hathayoga of 500 years ago. So most scholars hesitate to call modern yoga hathayoga, instead adopting other labels, like neo-hathayoga or modern postural yoga. It's easy to find things that pique our interest. We see or hear about something new—a new posture, sport, skill, craft or hobby. We think, "That would be good for me!" Or, "I might like that."

Soon, that initial excitement starts to fade. But, committed to the idea of our new passion, we still gather equipment, books, videos and anything else that we think might help us develop our new curiosity. Then those things sit there. The how-to books are in a pile, the equipment in a corner. Now we are left with a different type of wanting. This is not the desire to actually do or learn, but the want to want to do it. Now we have a choice: use discipline or move on. We can either double down and do the activity anyway, despite our lack of enthusiasm, or we can give it up and move on to something else. Either can be the right answer. It just depends on the goal. To determine which answer is the best one, we should consider the why. When it comes to a yoga practice, the why is very important. It is not a good reason to take up a yoga practice if we just want to see ourselves as a yogi, or have others see us this way. It's easy to get caught up in the idea of appearing spiritual without having the desire to actually walk the path. This is one reason for wanting to want to practice: we like the idea of what it would mean, but don't want to actually do the work. There may be other simpler reasons for wanting to want to practice. It could be that we simply feel tired and need to rest. But the desire to appear as though we practice yoga is important to be aware of. In this case, it may be better to give up the practice entirely. If our desire to practice yoga comes from the desire to strengthen our egoic self, it may be a more yogic action to give up yoga. Modern yoga practitioners often embrace the idea of equality and relate it to the ancient spiritual teachings of yoga. This can lead to positive developments like the cultivation of compassion and humility. But it can also lead to more troublesome developments like the belief that any suffering is in our own minds and therefore our own fault, which can cause us to be apathetic, overlooking ingrained prejudice and inequality.

Let's take a look at where the concept of 'equality' in yoga comes from, and what it means when someone says 'we are all one'. THE ESSENCE... In many ancient yogic texts, there is the belief that all of reality is underpinned by a single universal consciousness, called brahman. This means that a computer is nothing but brahman, a dog is nothing but brahman, you are nothing but brahman, and I am nothing but brahman. It is not unlike the recognition that all the objects in the universe are made of energy, whether that energy manifests as light, a hydrogen atom, a drop of water or a human being. When you look underneath the differences in external appearance, the same essence underlies everything. So when a yogi says 'we are all one', this really means that the essence which underlies all existence, including yours and mine, is the same. NAMES AND FORMS...AND HUMAN IMBALANCE But what this does not mean is that you and I are the same, nor that our experiences are the same. In the very same ancient texts is the recognition that when we are born as humans, we take on a distinct physical form that is separate from other forms. For example, I am separate from the computer, and I am separate from you. We take on a name and a form. Our essence is still brahman, but our names and forms are different. The goal of spiritual practice in this vein is to recognize our true essence as brahman rather than this body and mind. But it does not mean that our bodies, minds, histories, goals and identities are the same. The physical world is quite different from the spiritual world. We must recognize that we, as humans, create imbalance in the world. We take objects from one place and move them to another. We cut down trees to build houses, and we protect our own families by destroying others. While these things are all, by definition, brahman, that does not mean that our 'names and forms' are all inseparable. If it did, we would be just as happy to be eaten by a fish as to eat the fish ourselves. SPIRITUAL EQUALITY vs PHYSICAL EQUALITY While we may believe that we are the same on an essential, spiritual level, this certainly does not manifest into the physical realm of human bodies and minds. The way that the yogic concept of spiritual equality — that 'we are all one' — manifests in the world is infinitely complex and frustrating. Our human minds and bodies are designed to be selfish, even if our spirits are 'one'. We are born with the need to feed and protect our bodies at the expense of pretty much everything around us. This is what the yogis call 'ignorance' (avidya) and 'ego' (asmita), two foundational problems of every human. So next time someone says 'we are all one', recognize that it is a spiritual statement but not a physical, human one. If we seek to make the physical world more like the spiritual one, we must make the effort to subordinate our own desires to the good of others, and to make the human world more equal through our own action. Many of us believe that yoga is a reprieve from the hectic outside world. Our outer lives are fast and stressful while the inner yogic world is calm and peaceful. But yoga is a system that has real-world consequences. You may have noticed that your thoughts, beliefs and actions have changed since you began practicing or studying yoga. And when our actions change, consequences change.

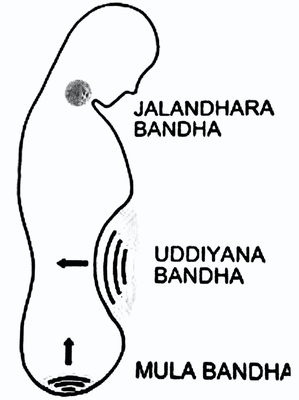

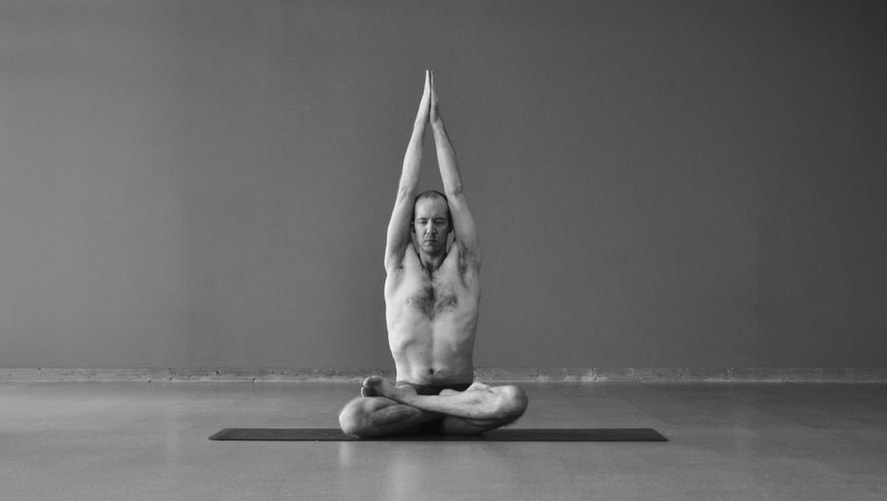

As such, yoga has a long history of interaction with social and political issues. It will be useful to examine some of yoga's core tenets, because they inevitably have an impact in the real world. We want to examine the real-world impact of yoga in three articles. This is the first. Here let's look at some of the fundamental tenets of yoga philosophy: non-violence & truth. NON-VIOLENCE A central belief in yoga and much Eastern philosophy is non-violence. At its heart, this is based upon the belief in karma: every action we do will come back to us later as a consequence. So if we harm someone else, that deed will return to us thanks to the universal law of cause and effect. We cannot possibly commit any action without reaping the consequences upon ourselves. In this way, we avoid violence as a form of self-protection. This belief is somewhat in contrast with the Western view of violence. We protect ourselves, our families, our possessions and our ideals with violence if necessary. Violence is justifiable in self-defense. Violence can even be morally encouraged if we think that the loss of 10 lives will save a million. Admittedly, this is complicated. It can be difficult to assess what we believe as individuals. But it is worth considering the varying viewpoints and their consequences. The yogic view, which avoids violence at literally all costs, has the possible repercussion of allowing the dominance of others who are willing to resort to violence. If I will not fight back, I will probably lose every battle I fight with someone who will. On the other hand, the self-preserving view, that permits violence in self-defense, encourages a highly-developed sense of identity and ego. It also encourages strenuous adherence to systems of belief, which can develop into violent action to defend those beliefs. TRUTH A yogic ideal with far less complexity is the idea of honesty or truth. To our knowledge, every culture encourages honesty. Our parents warned us from a young age, "Tell the truth! Don't lie!" The reasons why we choose honesty or lying are far more interesting. Most interesting are our reasons for lying. Ask yourself: "Why do I lie? When is it justified to avoid the truth or misrepresent it?" The reasons for lying can be distilled down to one word: power. We lie because it gives us power. When my boss asks why I'm late, I lie and say I got a flat tire. I have more power than I would if I told her the truth, which is that I slept through my alarm. Lying forces my boss to accept my version of reality, which allows me to dictate the consequences. Of course, this only works if my boss doesn't have access to other sources for the story. In that case, I don't have power over her version of reality. This is the great lesson of lying. It is only as powerful as its ability to bend the listener's view of reality. When someone lies to us and we believe it, we are completely under their power. However, if they lie to us and we do not believe it, they have no power over us whatsoever. Why does yoga encourage truth? Because it aligns us with reality. Every time we lie, we fracture ourselves from reality. If it is 2 o'clock but I say it is 10 o'clock, I have essentially separated myself from fact. I have constructed a small alternate universe and isolated myself from the real one. If we lie frequently, we remove ourselves from reality and increasingly exist in a bubble of our own making. Yoga's goal is to reverse this process and gradually place us firmly and directly in reality. Not our own thoughts or beliefs, but reality itself. Try it for yourself. Next time you are tempted to tell a lie, no matter how small, tell the truth instead. Your individual sense of power will decrease, but this is only a false sense that is driven by the ego. What improves is your connection to truth, which actually makes you immensely more powerful. IN CONCLUSION The way in which we relate to the world has real consequences. This includes how we think of ourselves and our beliefs. Are we willing to fight for them? Who are we fighting and why? Is violence justified by its outcome? Does the end justify the means? Will we lie to protect our identity, possessions or power? Will we accept the lies of others to do the same? Yogic philosophy answers these questions in specific ways. But that is not terribly important here. What is important is that we consider these questions. And realize that how we answer them will have real-world impact. Mula bandha is a somewhat common technique in modern yoga. It is generally accepted that this technique, which means 'root lock', is a contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor. Some interpret this to be the perineum, the anus, or a combination of the muscles in the pelvis. The anatomical specifics of how and when to do mula bandha are not the goal of this article. Today we are looking at where the practice comes from, and perhaps why it was developed. The instruction of mula bandha dates back to the early days of Hathayoga, around the 12-13th centuries CE. At this time, Hathayoga was gradually forming out of the tantric beliefs of Buddhism and Shaivism. Alchemy, the attempt to forge new substances, was widely accepted, and the spiritual seekers began practicing an 'inner alchemy' where the magic happens inside the body of the yogi. According to this alchemical belief, the inner elements of a person could be forged to create immortality, divinity or great power. As Shaivism (the worship of Shiva) became more prominent in Hathayogic teaching, the concept was related specifically to the awakening of kundalini, a latent power of pure consciousness. The way that kundalini is awakened is by manipulating the 'winds' of the body, some of which naturally go up while others go down. In Hathayoga, mula bandha is specifically intended to take the downward-moving 'wind', called apana, and push it upward. Once the apana wind is turned upward, it is fanned with the abdomen to heat it. Then it combines with the upward wind, called prana. The combination creates an inferno that awakens and raises kundalini. Below is an excerpt from the Hathapradipika, perhaps the best known text on Hathayoga:

As you can see, mula bandha is specifically intended to turn apana upward, where a whole series of events follows. This description of mula bandha is present in almost all the texts of Hathayoga. Here is one other, from the Goraksasataka, translated by James Mallinson. I include it because it is pretty elaborate and well-explained:

This explanation continues to the modern day, though it is rarely incorporated in common yoga posture classes that remove esoteric or spiritual overtones. For obvious reasons, a simple muscular contraction is far easier to teach and understand than a detailed metaphysical system of bodily winds and latent spiritual energy. Nonetheless, Swami Sivananda and his students like Vishnudevananda explain mula bandha similar to the older Hathayogic way. Iyengar, in Light On Yoga, foregoes the apana-kundalini approach and explains mula bandha a little differently. He initially explains the bandhas as closing off "safety valves", which is reminiscent of the old way. But he goes on to interpret the term mula bandha as follows: mula means 'source', and bandha is 'restraint'. So mula bandha is the restraint of the mind, intellect and ego. This recalls Patanjali's famous definition of yoga at the beginning of the Yoga Sutras. Here is what Iyengar writes in Light On Yoga:

We don't think it's a stretch to say that this is a reinterpretation of the meaning of mula bandha. Separately, in modern practice and teaching mula bandha is sometimes taught as a physically stabilizing technique, again quite different from its original iteration.

What does it all mean? Like so many things in yoga, the purpose of the practices can change so that they become unrecognizable. Does that make them less effective, useful or valuable? Perhaps. We think it is worth asking ourselves why we do what we do. What are the underlying reasons? Personally speaking, we do not hold the belief that our bodies are populated by 'winds', as was apparently the belief for some time during the development of Hathayoga. We attribute our 'digestive fire' not to actual fire but to hydrochloric acid in the stomach. And we attribute urination and excretion not to downward-moving apana wind but to peristaltic movement of the intestines and contraction of the sphincters. Do these beliefs make something like mula bandha anachronistic? We think that they do. Samadhi is an important concept in yoga. It is the highest of the 8 'limbs' in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and the highest of the 6 'limbs' of the Maitri Upanishad. Even with such a distinguished position as the culmination of yogic practice, it is a difficult concept to understand. Often samadhi is described as 'absorption', 'meditation', or 'contemplation'. I think it is much clearer to think of it as 'transparency of mind'.

One of difficulties with samadhi is the same as will arise with any other word. Most words have multiple meanings, and it can be a challenge to pinpoint the correct one. Samadhi is often used in a more general sense meaning 'concentration'. So we often see it used in contemplative, yogic and spiritual texts without a super technical purpose. Often it just means concentration. But in yoga texts around 0-500 CE, samadhi took on a more specific, technical meaning. It was placed atop of the pyramid of meditative practice, above the older, better-known dhyana, which was until then a more common term for meditation. THE COLOR OF THE MIND To understand the value of samadhi, first we must understand the nature of the mind. As a thinking and perceiving tool, the mind is always interpreting what it sees and combining it with what it has experienced in the past. This interaction of the present with our memory is what gives us our 'reality'. But it is dependent on our past experience and the beliefs it has created. So we are not actually experiencing the world as it truly is but interpreting it through the lens of our own history. The mind is like stained glass. We can see the world on the other side, but it is distorted and colored by our own experience, history and memory. The practice of yoga is largely committed to reducing the 'color' of the mind, working toward removing the distortions of our perception and the impact of the mind's own tendencies on our interaction with the world. A TRANSPARENT JEWEL Samadhi is the ultimate expression of mental transparency, where the mind no longer interprets the world through a 'colored' filter. As it says in the Yoga Sutras, "the mind becomes just like a transparent jewel, taking the form of whatever object is placed before it" (YS 1.41). This means that there is no distortion whatsoever caused by the mind, and we can experience each object exactly as it is without our own interpretation. Similarly, samadhi is described later in the sutras as the state when "the mind is devoid of its own reflective nature" (3.3). This is a difficult state to achieve, as the tendency of the mind is mostly toward interpretation. Meditative practices are largely aimed at solving this problem by encouraging a 'one-pointed' mind. This reduces the tendency of the mind to think, interpret and color our perceptions. The culmination, samadhi, is when we cease to interpret the world, make the mind transparent, and experience the world as it is. Along with the introduction of modern physical practices, a lot has been lost in the world of breath control practices as they were documented through yogic texts for many hundreds of years. Pranayama is most easily translated as breath control, but “prana” means one’s life force. Pranayama is therefore, the control of one’s life force as accessed through the breath.

There are many benefits to controlling the breath. These benefits continue to be brought to the forefront through scientific study. Benefits range from relaxation to potentially suppressing tumor growth in the body. While the studies are magnificent in their potential, the most powerful reason to cultivate the breath in yoga is because of its intermediary relationship to the body and the mind. When we access and manipulate the breath, we use two different parts of our brain. We also can access the two parts of our autonomic nervous system by changing how we breathe. If that wasn’t enough, we can also choose which nostrils we breathe through and stimulate our olfactory nerve which has a direct relationship with our brain. Many of us might question the necessity of these types of practices since our breath is an automatic function. However, it is easy to make the judgement that breath manipulation is unnecessary when we have not experienced the results. Once you realize breathing can reduce stress, focus the mind, and possibly suppress cancerous tumors, it seems an obvious practice to undertake. When we strengthen our awareness of the body through asanas, we are mostly concerned with our muscles, bones and structural tissues. We get stronger muscles, and ease muscular tension. The benefits often translate into other systems of the body which result in things like better circulation or digestion. However it is not until we get into pranayama that we experience the body on a deeper plane. The awareness we get from breathing is the awareness of our nervous system. It is a deep and profound level of awareness that leads us to a level untouched by most: experiencing the mind. Most of the time we experience our thoughts. We never think about thinking, we only react to our thoughts. We get lost in the result of our thoughts, but not in what caused them to begin with. A very common example of this phenomenon involves the idea of a movie and the screen on which the movie is projected onto. When we watch a movie, we know it is not real. The screen is blank before the movie begins and is blank after the movie finishes. We just accept this. However our minds are no different! They are blank before a thought arises and blank after the thought finishes. The problem is that we mistake the thoughts for reality. Through stillness, we can learn to identify the “movie screen” of our minds as reality, not the fleeting thoughts that project onto our mind. Pranayama, and working to still the breath, is the gateway into stillness of the mind. There is a common belief in modern yoga that we are all one on the deepest level. It has the impact of making us feel more connected to each other while also empowering us. It comes from a tradition of belief in which the highest element, called Brahman, permeates all forms of existence including ourselves.

But there is a problem when we---ordinary people going about our lives of work and family---take this belief literally and apply it to ourselves. We live in a world ruled by our body and senses: we get hungry, we respond to emails, we watch movies and cute cat videos, we take vacations to warm beaches, we drink alcohol, etc. While the belief that we are all one or I am divine may be true on the essential level of existence, it does not apply to the gross body or the minds (like ours) that are attached to it. It only applies to those beings who, as Ramakrishna said, have "overcome the consciousness of the physical self." Otherwise, "'I am [divine]'---this is not a wholesome attitude...He deceives others and deceives himself as well." The problem is that we associate our self with our body and mind. This association is in our mind, where we imagine our identity and closely relate it to our physical existence. If we then add on the belief that I am divine, the complete meaning is actually My physical existence is divine. The difficult distinction that we must make is recognizing that our true self does not lie in the body or mind. It is this self beyond the physical realm that is referred to in the phrases we are all one and I am divine. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are known as the fundamental text for the system of yoga. They are brief and dense, only 195 short verses, and they can be difficult to understand by themselves.

The sutras are not really intended to be understood without the explanation of a knowledgable teacher, and there is a long tradition of great teachers writing commentaries and explanations of each individual sutra. "Our understanding of Patanjali's text is completely dependent on the interpretations of later commentaries; it is incomprehensible, in places, in its own terms." (1) The first and best-known commentator to explain the sutras was Vyasa, from around the 4th or 5th century CE. Vyasa's commentary is practically inextricable from the sutras themselves and known as the bhashya, which means "commentary." "It cannot be overstated that Yoga philosophy is Patanjali's philosophy as understood and articulated by Vyasa." (2) It has been about 1600 years since the Yoga Sutras were created. In just the past 100-200 years, the understanding of yoga and the sutras themselves has changed somewhat, mostly due to modernization and recent philosophical developments. But in the prior 1500 years the Yoga Sutras were "remarkably consistent in their interpretations of the essential metaphysics of the system." (3) Modern yoga has gotten far from the values of the Yoga Sutras, which focus on the concentration of the mind and emptying its constructed identities to find its underlying reality. Modern interpretations of the Sutras can be shaded by Vedanta---an old Indian belief system that is separate from the Samkhya system of the Yoga Sutras---new-age philosophies and Western modalities. As yogis, the Yoga Sutras have a lot of insight to offer, and the accompanying commentaries are vital to understanding the sutras themselves. So when you pick up a copy of the sutras, try to find one with a traditional commentary. It will help you understand the intended meaning of this important text. 1. Bryant, Edwin. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, North Point Press, New York, 2009, p.xxxviii. 2. Ibid. p.xl 3. Ibid. p.xxxix |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed