Dr James Mallinson - keynote presentation at YDYS 2024 (Photo by Corinna Lhoir) Dr James Mallinson - keynote presentation at YDYS 2024 (Photo by Corinna Lhoir) This past week, we had the opportunity to be a part of the Yoga Darshana, Yoga Sadhana Research Conference in Hamburg, Germany. It was a fantastic few days of yoga scholarship and discussion in a variety of topics related to the histories and practices of yoga. Scott presented on the history, complexity and understandings of early prana and pranayama. He focused on the centuries before and after the turn of the common era. Ida presented on the history of women in yoga within early 20th century India. We had a lot of time to catch up with fellow researchers of yoga, including former classmates from SOAS University of London. We also heard presentations by so many incredible scholars! One highlight was to hear from much of the team that was the Hatha Yoga Project: http://hyp.soas.ac.uk/.  with Jason Birch of https://www.theluminescent.org with Jason Birch of https://www.theluminescent.org The keynote presentation by James Mallinson will be available on Youtube. We will share it here when it's available. Massive thanks to Jason Birch for a copy of his new book! We heard from the organizers that the next conference will be in Paris or Zurich in 2026. The conference is open to the public so if you are interested in yoga scholarship, keep your eyes open for info on the next event. We'd like to thank the organizers and all our fellow presenters and attendees for making the conference a great event. We already look forward to 2026!

0 Comments

We often hear people say, "There's just so much information out there and I don't know where to turn." We get it. There is a lot of material available. But not all of it is of the same quality.

So, what do we do? How do we all navigate continuing to learn while making sure that what we are learning is quality information? The first question is, how do we define quality? There are a few questions we can each ask ourselves when we're presented with new information. These will help us figure out how seriously to take the information. Here they are:

Let's break these down a little further... Everyone has an opinion on everything. Even the phrase "I don't have an opinion on that" means that we have a non-distinct opinion. That too is a point of view! The opinion of a person is always valid as the opinion of that person. We should always listen and seriously consider the beliefs of others. But we should not always take the opinion of one person as objectively true, or think we also need to believe it. It is true that it is an opinion. Though that doesn't necessarily mean that the content of the opinion is true. We need to be careful when we hear an opinion, and make sure that we take into account how other sources of information agree with or critique that opinion. If there are other sources that confirm it, this is considered evidence to support the opinion. If we find that there is a variety of evidence from multiple different places in support, the opinion is more likely to be valid as information. Furthermore, we should be careful when people talk about subjects that they are not expert in, even if that person is an expert in a different field. It is easy to revere others and think highly of their skillset. But that doesn't mean that they are experts or skilled in fields other than the one they are expert in. Do you want your dentist to operate on your heart? Or fix your car? Or write you a poem? While there is a lot of information out in the world, not all of it is worth learning. In fact, much of it is not. The information that is backed by evidence and comes from an expert in their field is far more likely to be worth learning than the opinion of someone who is speaking about something they don't know much about. There is a new Journal of Yoga Studies available for download. Volume 5 includes three new articles on yoga research, including one written by Ida on Bengali yoga manuals.

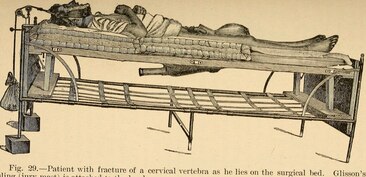

Enjoy! Read the JoYS here: https://journalofyogastudies.org  From "Saunders Medical Hand-Atlases - Fractures and Disclocations", 1902 From "Saunders Medical Hand-Atlases - Fractures and Disclocations", 1902 Traction the spine! Natural human traction! We hear these phrases in yoga classes. But what is traction? Do postures really provide traction?! The quick answer: No, yoga postures do not traction the spine. Here is why. CONTEXT Traction Therapy is defined as a technique that separates the spinal vertebrae by mechanical force. Interestingly, there is evidence of the use of traction dating back 4,000 years. Historical records show that even Hippocrates invented an apparatus to traction the spine around the 4th century BCE. TWENTIETH CENTURY The early twentieth century was the era when asana flourished and health of the body was of primary importance to the evolving practice of yoga. Not coincidentally, this was also an era when low back pain was commonly being treated using traction devices. Given this overlap, the language of traction in yoga makes sense as yoga swallowed up a lot of health-based language of the era. (Other examples include the focus on the spine in general, deep breathing, circulation, focusing on the organs and glands, to name a few.) Furthermore, it makes sense that since traction was popular in the early twentieth century particularly within British medicine, that it would influence modern yoga as it developed in Colonial India. Today traction is most often used as a method to reset a dislocated joint. Significant external force is applied to put the body back together from an injury. It is less common that traction is used today as a therapy.  It is commonly said that traction occurs in Balancing Stick, but this is not physically possible due to the lack of apparatus. It is commonly said that traction occurs in Balancing Stick, but this is not physically possible due to the lack of apparatus. TRACTION IN YOGA As we saw from the definition above, traction requires external force. Mechanical force is applied to the body. This force can come from weights or pulleys. So, can we use traction in a bodyweight movement? The answer is no. We cannot traction in yoga, because there is no external force. Often it is said that reaching the arms tractions the spine. But this is not the case. The shoulders actually get there stability from the spine and do not move the spine. Any reaching with the arms is called shoulder elevation, essentially engagement of the upper trapezius, rhomboids and levator scapulae. Even if two people pull on the arms and lifted leg in Balancing Stick, this will still not traction the spine. This is because the joints that would be receiving the force of the pull are the wrists, elbows, shoulders and the ankles, knees and hips. These are not the spine. SUMMARY While the language of traction makes sense for the evolution of yoga, actual traction is not possible in a bodyweight movement. (The small caveat to this the use of gravity in very specific circumstances.) Traction requires external force. However in postures where traction is taught, like Balancing Stick for example, the spine cannot traction because there is nothing pulling on it. Any movement of the body which makes the spine look like it is getting longer, is not actually the vertebrae separating. There is not a scenario in which "natural human traction" without external force is possible. Even Hippocrates needed a contraption to traction the spine. Source: Ralph E. Gay, Jeffrey S. Brault, CHAPTER 15 - Traction Therapy, Editor(s): Simon Dagenais, Scott Haldeman, Evidence-Based Management of Low Back Pain, Mosby, 2012, Pages 205-215, (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323072939000155) Yoga is constantly being defined. Nearly everyone in the yoga world seems willing and eager to tell you what yoga means. This is often paired with judgement about all the things yoga is not. The person defining it usually assumes that they are correct and that anyone who doesn't agree with them is incorrect. So really, what is the definition of yoga? There is no singular definition of yoga. Anyone who tells you otherwise is actually suggesting what yoga means to them, not what yoga means. Yoga is a vast concept, which has moved across time, place, culture and context. As a practice, yoga can be material or transcendent, literal or figurative. It can be religious or secular. It can be a practice to cultivate the body or a practice to destroy it. For the Classical Yogis, yoga is the goal. For the Jains, yoga is a problem. Yoga is exercise for some practitioners today. For others, it is offensive that anyone considers it to be exercise. Historians on yoga explore how the meaning of yoga has always been in flux. It has always evolved and been defined then redefined. Foxen and Kuberry write "the fact of the matter is that ‘yoga’ is a very basic and generic type of word” and “yoga practices (the entire spectrum of them) have continuously changed and evolved in tandem with the culture around them” (Foxen & Kuberry 2021, p. 5). Do you think about the definition of yoga? Do you feel strongly that it means a specific thing? We will all certainly have personal opinions on yoga. But we should not mistake our views on what yoga is as the one definition of yoga. Anyone who defines yoga is not defining yoga. They are defining what yoga means to them. Source:

Foxen & Kuberry, 2021. Is This Yoga?: Concepts, Histories and Complexities of Modern Practice. Routledge. In this blog series, we will explore the difficult tendencies of the mind as taught and described by various traditions of meditation. Buddhism suggests that there is suffering, and suffering arises from desire. This desire is referred to as thirst or craving. If we all have desire, and therefore suffering, where does it come from?

In Buddhism, desire comes from greed. We can want any number of things. Cravings are endless. There might be sensory desires like foods or drinks, experiential cravings like entertainment or travel, or egoic desires like fame or power. These can be linked to each other-- a meal that makes us feel like a king or queen, for example. In this case, there is sensory craving alongside a sense of power or stature. The teaching on greed and desire suggests that it does not matter what the object of craving is, it is craving itself which is the root of suffering. We have to eliminate desire to eliminate suffering. We cannot simply eliminate the objects of our desire. Let's look at some textual passages. In the Buddha's Final Nibbana, it states: When one gives, merit increases; when one is in control of oneself, hostility is not stored up; The skillful man gives up what is bad; with the destruction of greed, hatred and delusion he is at peace.* If greed is the problem, instead one should give. This gets at the idea of cultivating the opposite, which is also found in the Yoga Sutras: When one is plagued by ideas that prevent the moral principles and observances, one can counter them by cultivating the opposite. Cultivating the opposite is realizing that perverse ideas, such as the idea of violence, result in endless suffering and ignorance--whether the ideas are acted out, instigated, or sanctioned, whether motivated by greed, anger, or delusion, whether mild, moderate, or extreme.** The idea is to cultivate the opposite of greed or desire. If we do so, we will realize that greed only results in suffering. What are some ways we can cultivate the opposite of greed and desire? Sources: * Mahaparinibbana Sutta, D II 72-168 in Gethin, R. 2008. Sayings of the Buddha. Oxford World's Classics: Oxford, pp. 78 ** Yoga Sutras 2.33-34 in Stoler Miller, B. 1995. Yoga Discipline of Freedom. Bantham Books: New York Gethin, R. 1998. The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press: Oxford In this blog series, we will explore the difficult tendencies of the mind as taught and described by various traditions of meditation. The Buddhist meditative tradition teaches that there are five hinderances of the mind. These are mental factors or states that exist and arise in the mind. These qualities prevent the practitioner from making progress in meditation.

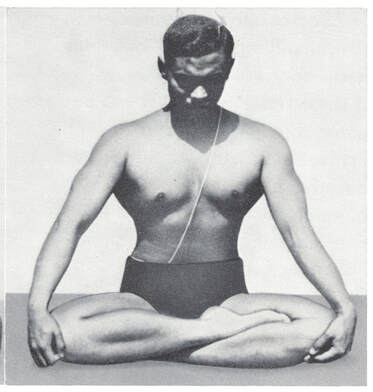

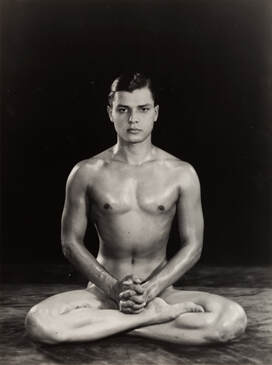

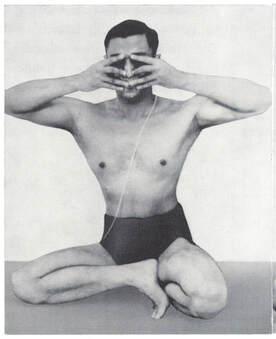

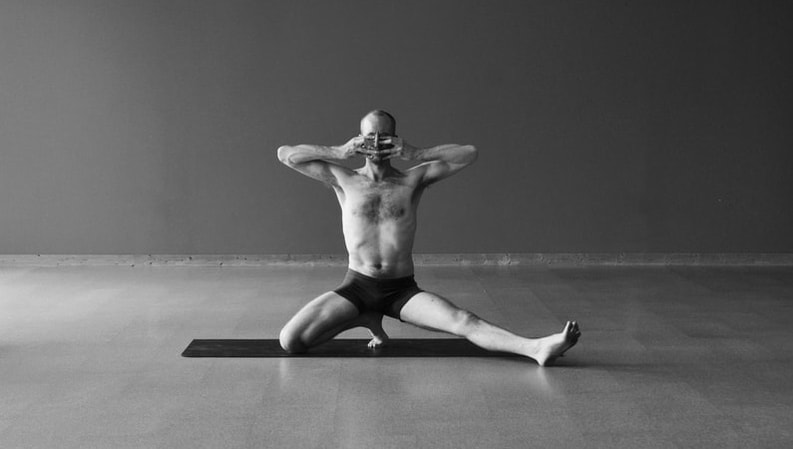

The five hinderances, as taught in Establishing Mindfulness (Satipatthana Sutta)* are: 1) sensory desire, 2) hostility or ill-will, 3) dullness or lethargy, 4) agitation or worry, 5) doubt. It is the practice of mindfulness that allows us to recognize these qualities in the mind. The practitioner recognizes when they are present and when they are not present. Through practice, if and when these qualities are abandoned, the practitioner knows they will not arise in the mind again. The practice of mindfulness consists of sitting in contemplation and establishing mindfulness. There are four phases: mindfulness of the body, feelings, mind and qualities. Within the explanation of the last section, qualities, is the explanation of the five hinderances. It is taught that if one is able to live in recognition that there are these qualities, one can be aware as they come and go without holding onto them. Source: * Satipatthana Sutta, M I 60 - Sayings of the Buddha, Rupert Gethin, pp. 147-148.  Swastikasana, by Gouri Shankar Mukerji Swastikasana, by Gouri Shankar Mukerji Through our research and practice, we have found confusion regarding the names and positions of two seated postures: Swastikasana and Siddhasana. Swastikasana is left untranslated as "Swastika", or understood as Auspicious, Good Luck or Twisted Cross Pose. Siddhasana is called the Siddha's or Adept's Pose, or Success in Meditation. Up until the 1970s or even later, Swastikasana was typically a seated, cross-legged position with the feet intertwined between the legs. This instruction is given by teachers of the Ghosh lineage such as Buddha Bose and Gouri Shankar Mukerji. It's also found in texts of hathayoga that predate the twentieth century.  Swastikasana, by Buddha Bose Swastikasana, by Buddha Bose The Hathapradipika instructs Swastikasana as follows: "Placing the soles of both feet well between the knees and thighs [and] sitting up with the body straight: they call that the auspicious pose*" HP 1.19 (See *below for note and credit on translation). However, Bikram Choudhury in his list of "84", mistakes Siddhasana for Swastikasana. He teaches it as the position pictured at the top of this blog: balancing, resting on one heel, using the fingers to close off the senses. However, this is much closer to what Gouri Shankar Mukerji teaches as Siddhasana.  Siddhasana, by Gouri Shankar Mukerji Siddhasana, by Gouri Shankar Mukerji In 84 Yoga Asanas, Gouri Shankar Mukerji instructs Siddhasana as follows: "Sit on one heel, blocking the anus. Hold this heel in place with the other heel. Inhale. Now close all apertures on your face with your fingers. The right thumb on the right ear and the left thumb on the left ear, right forefinger on the right eye and the left forefinger on the left eye, left middle finger on the left nostril and the right middle finger on the right nostril, right ring and small fingers on the mouth (halfway) and the left ring and small fingers on the other side of the mouth. Thus all openings on your face are blocked with your ten fingers" (p. 59). Given this history, there is great confusion over the name of the posture at the top of the page. While some call it "Good Luck", we suggest it should not be called that given the fact there is a posture consistently performed as Swastikasana, Good Luck, that is different in shape. The straight-leg version pictured above is a new posture if we look at yoga's history beyond the last few decades. For this reason, we would suggest it should take on a new name. * This translation is from Hathapradipika.online which is the work of Dr James Mallinson, Dr Jason Birch, Prof. Dr. Jürgen Hanneder and Dr Mitsuyo Demoto-Hahn. They are working on Light on Hatha Yoga: A critical edition and translation of the Hathapradipika, the most important premodern text on physical yoga.

We are ever grateful for their work and look forward to the final publication. There seems to be an endless focus on the arms in yoga postures. This comes in the form of discussing which finger position or grip is the most effective, whether or not the elbows are straight, or what the shoulders should look like.

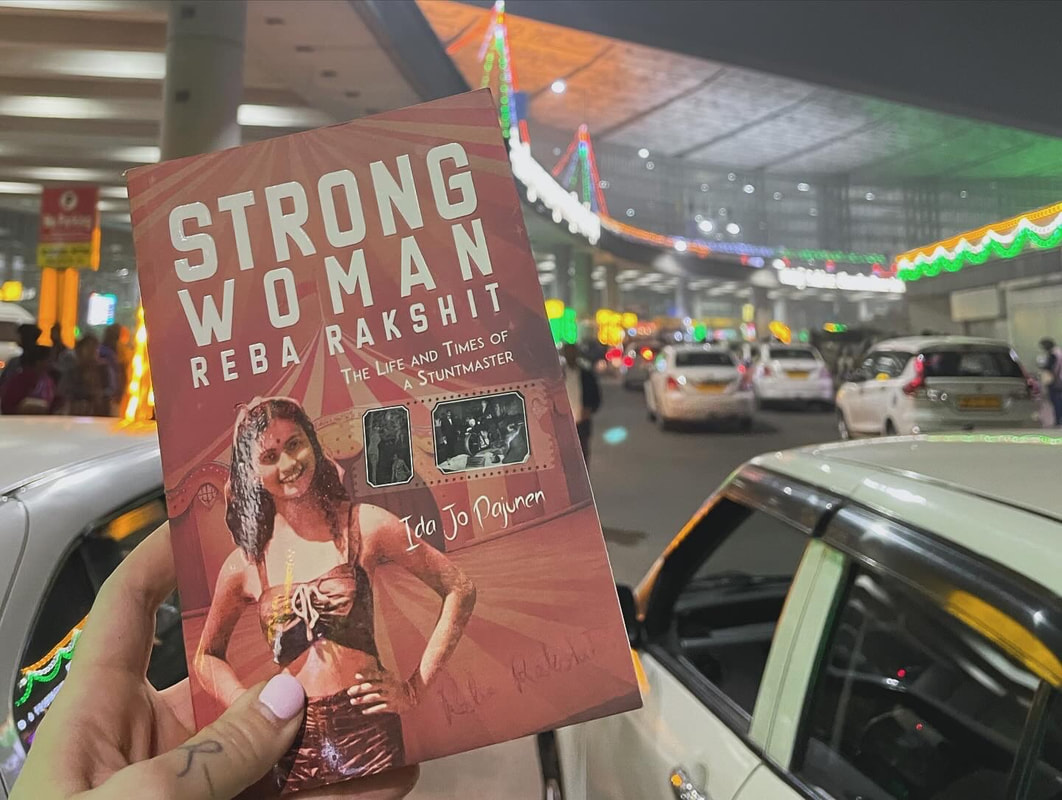

This is usually not useful. Unless we are talking about an arm pose like Crow or Plank, it will not help us to focus on the hands, elbows or shoulders. Here is why... The majority of postures are about the spine. The arms do not move the spine. The muscles that move the spine are the muscles that move the spine: abdominal and back muscles. So if we are trying to move the spine, it won't help us to focus on the arms. TWO COMMON MISUNDERSTANDINGS There are two common misunderstandings at play here. The first is that the spine can change length. It can change shape, but this is not the same as the spine itself actually growing longer. The spine is a fixed length. There are vertebrae and discs that make up the spine. The spine itself cannot lengthen. One side of the spine can lengthen, but it does so by the other side of the spine shortening. This is what we do in backward and forward bends. In a backward bend the front of the body does get longer, but that's because the back gets shorter. If we want to change the position of the spine, we have to do so one side (front, back, left, right) at a time. The second misunderstanding is confusing shoulder elevation for spine length. In the picture above, the spine is no longer than with the arms down by the side. It is only that the shoulders are elevated, or to say it another way, the shoulders are shrugged up by the ears. This is trapezius engagement. With the arms overhead and the trapezius engaged, it may look like the spine is longer, but in fact it is an optical illusion. It is just the arms and the shoulders that have moved. Often, it is said that reaching with the arms will help bend the spine. But reaching with the arms moves the shoulders. Some shoulder muscles, namely the trapezius and the rhomboids, do attach to the spine. But they get their stability from the spine in order to move the shoulder blades. These are not muscles that change the shape of the spinal column. To put it simply, the spinal muscles move the spine. The arms, shoulders and hands do not. In spinal postures, do not worry about lengthening your spine or using your arms. Try to put your focus on the muscles that move the spine. Join us for the Strong Woman Reba Rakshit book club! Since March is Women's History Month, we thought this would be the perfect time to read Reba's story together. Then at the end of the month we will discuss the book and topics related to women in yoga. Join us March 30th for a free, online book discussion. You can register below.

Strong Woman Reba Rakshit is a biography of a yogi and circus star set in the 1950s. She was a student of Bishnu Charan Ghosh and a woman who dared to dream. She had immense courage and steely determination. She was a stuntmaster who worked shoulder to shoulder with men to give her country its first ‘strong woman’. Over the month, we will pose questions and points for reflection. If you choose to read the book, feel free to share your thoughts and send us your questions. On social media, tag or mention Ghosh Yoga and use hashtags #ghoshyoga and #strongwomanreba If you don't have a copy, they are available now. Book discussion RSVP: forms.gle/ufwRs1uqiFHXLrmm7 |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed