|

Therapeutic exercises are simple movements of the body that take the major joints and muscles through their functional range of motion. They are not fancy or particularly beautiful to look at, but they are quite useful to keep the body strong, mobile and painless.

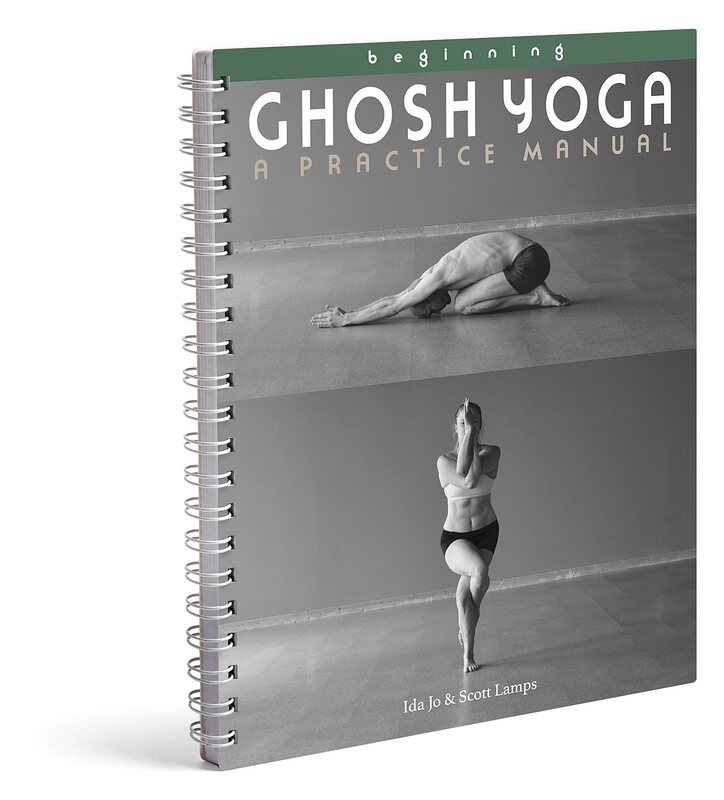

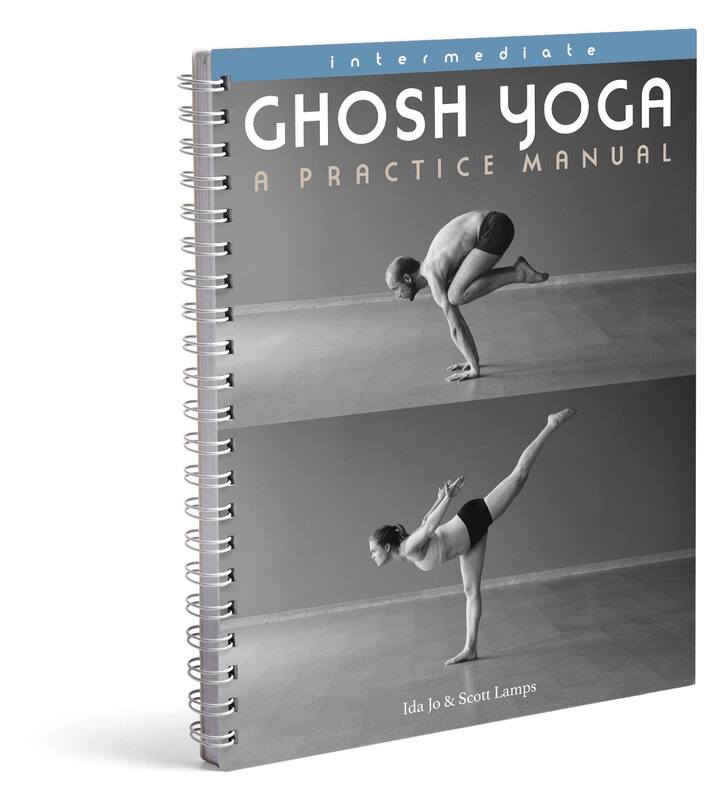

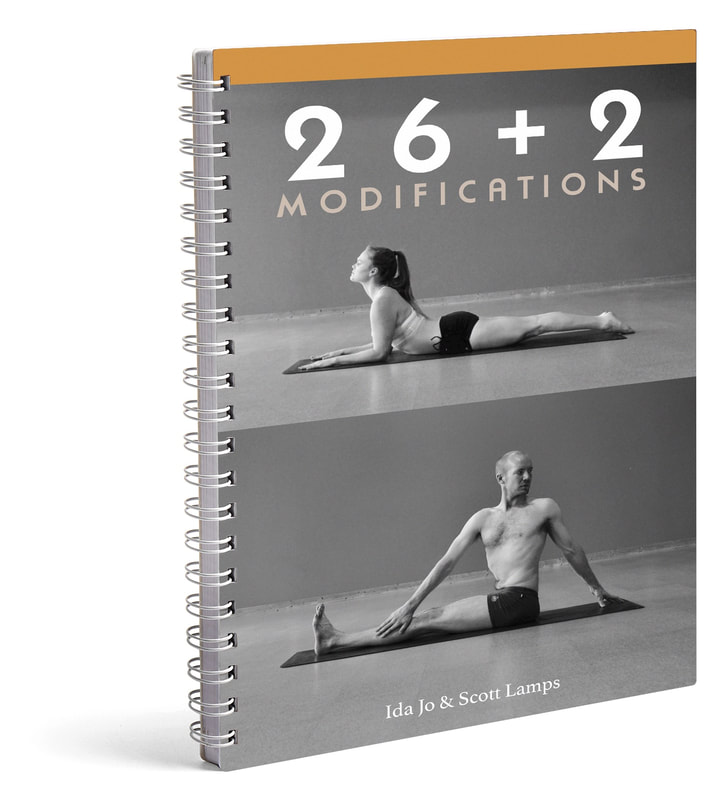

These exercises are the basis for the yoga method taught at Ghosh's Yoga College in Kolkata, India. They are central to the goal of building and sustaining health. Because modern life is full of imbalances — lots of sitting, hunching and looking at screens — our bodies and minds get out of whack pretty often. We get tight hips, tight lower backs, achy necks, tight shoulders, etc. Most often, these tight achy areas are directly linked to an imbalance in a major joint. On the opposite side of the tightness is weakness. We use these Therapeutic Exercises as precisely as we can to target the issues in the body. Some exercises are good for balancing the lower spine — like the Torso Lift and Leg Lift — while others are good for balancing the upper spine — like Cobra and Full Locust. Still other exercises are useful for balancing the hip — like Squatting and Hip Hinge — or the shoulders — like Butterfly or Chest Expansion. After years of consideration and discussion with the Ghosh family, we are finally releasing a book that contains more than 40 Therapeutic Exercises. We try to explain the use of each exercise as precisely as possible, both what it does in the body and what imbalances it is good for. At the end of the book are a handful of practice sequences. You may know that 'sequences' are unusual in therapeutic yoga, as each person is different and gets a unique prescription. But we have identified a few of the most common issues and imbalances and provided sets of exercises to target them. We truly hope that this book will be useful to you, whether you are a beginning student, have an injury, are a yoga teacher, a yoga therapist or a historian of this method. The book is available for preorder here. It will ship on December 7.

4 Comments

Over the last few months I’ve been compiling materials to research the forgotten women of yoga. Through work in Kolkata, I came to know of a few names of women, some quite famous, who today are completely forgotten. The questions started piling up— why do so many women do yoga when it was thrust into the modern age largely (at least publicly) by men.

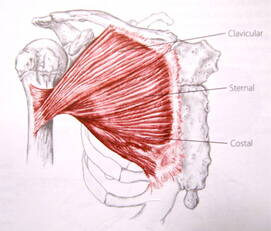

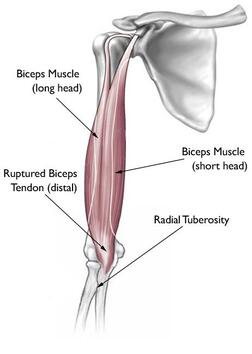

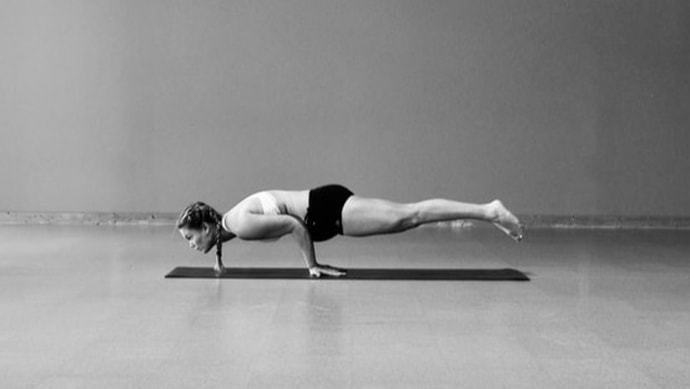

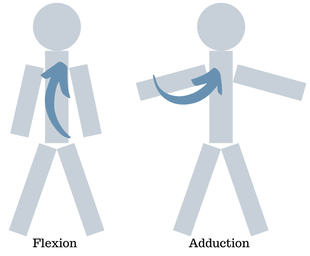

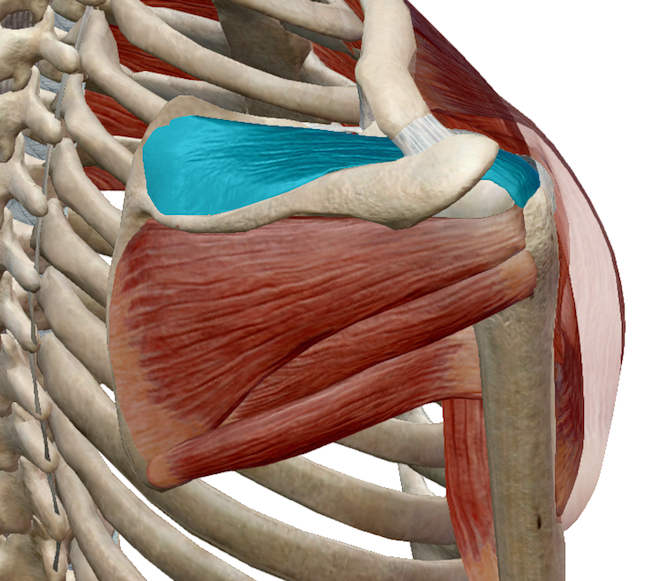

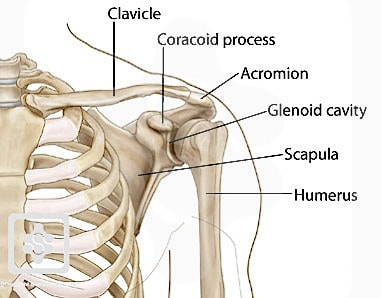

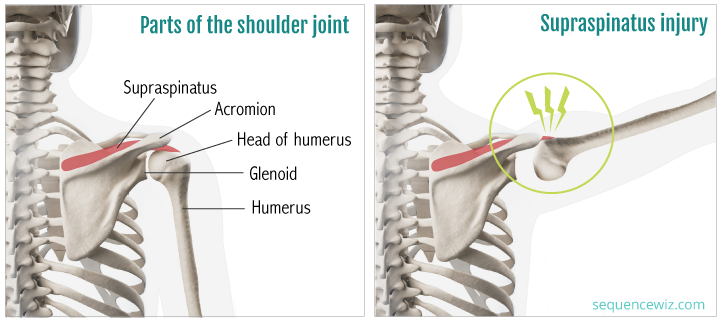

Through gathering texts and doing interviews, the layers of complexity grew. One unanticipated layer is the talk of beauty when it comes to women and yoga. This isn't found in posture manuals for men, and isn’t about “radiance” or something that could be referenced in Haṭha texts. This is talk of things like “perfect breasts” and “thin waists”. This made me think of my own journey in the yoga studio so far. The "no food is good food" was certainly a part of the community. I remember being complimented the most in class when I was incredibly sick with pneumonia and hadn't been able to keep any food but applesauce down. Around that same time I was also injured. My hamstring was tearing but I was locking out my standing bow. (Worth it? No.) Since then I stopped wanting to be injured and took up weight training. When my new trainer gave me 15 pushups as a warm up I balked! I couldn’t do one, yet I was one of the strongest at my yoga studio. I have since gained 15lbs. And with it, the strength to run many miles, move hundreds of pounds, do pull-ups, (more than 15) pushups and most importantly, have the strength to stay injury free. Since talking about injuries in yoga studios around the world, we've gotten a variety of responses. Some burst into tears and ask, “So it shouldn’t hurt? I’ve spent a decade thinking it was supposed to.” Some just shake their heads, acknowledge how obvious it is that a "healing" practice shouldn’t injure the body. Others though, respond with the predictable, yet disappointing response of, “Well I’m not injured. You weren’t doing it right.” Denial is powerful. All of this combined has me thinking. Are we trying to be healthy or beautiful? Who is deciding this? Do we actually know what we’re doing? This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. Last month we wrote about the common shoulder injury Shoulder Impingement. The other common injury to the shoulder happens in the front, where the short head of the biceps muscle attaches to the shoulder blade, a biceps tendon strain. This injury is most common in Ashtanga Vinyasa and subsequent 'flowing' yoga styles that incorporate a lot of Sun Salutations and chaturangas. The shoulder can't do this action very well, and the biceps become strained before too long.  Pectoralis major ("pec") Pectoralis major ("pec") To understand this injury, we have to talk about shoulder mechanics and the muscles that move the arm. PECTORALIS MAJOR & ADDUCTION One of the biggest and most powerful muscles of the shoulder is the pectoralis major, commonly known as the 'pecs' or just the 'chest muscle', pictured to the left. It connects the arm (humerus) directly to the middle of the chest. Its main function is to pull the arm toward the chest in an action called adduction. Try it: hold your arm out to the side (as pictured below, labeled adduction), then bring your arm toward the center, so you end up with your arm pointing forward. As you do this, you will feel your 'pec' engage. When you apply this motion to something like a pushup, the arms need to be away from the body, so the pushup motion will be pulling the arm inward toward the chest. Simply put, this means keeping your elbows away from the body. This is the safest way to do any pushup motion.  BICEPS & FLEXION In contrast, if we start with our arms down by the sides and lift them up until they point forward, this is called flexion (pictured above, labeled flexion). When we lift the arm like this, the pec doesn't get activated much, so the work is done by much smaller muscles like the anterior deltoid (the front of the shoulder cap) and the biceps. The biceps cross two joints; they bend the elbow and also flex the shoulder. But they don't have the power to move the body's entire weight. When we do pushups or chaturangas with the elbows close to the sides of the body, we are essentially moving the shoulder in flexion. This is not a powerful nor particularly healthy way to move so much weight. When we do this repeatedly, the bicep tendon (usually the short head at the attachment with the coracoid process of the shoulder blade) will often be damaged. This manifests as pain or soreness in the front of the shoulder. There is a common belief that keeping the elbows close to the body uses the triceps more than if the elbows were wider. This is not true for the simple reason that the triceps straighten the elbow, and the elbow is doing a similar action in both versions. The big impact is on the shoulder and what muscle group you use when doing a pushup or chaturanga motion. IN CONCLUSION There is nothing inherently wrong with keeping the elbows close to the body and flexing the shoulder. The problems arise when we do this with our entire body weight and do it repetitively. This is how injury usually happens. Consider making the elbows wider, which will strengthen the huge pectoralis major muscle as well as be safer for the smaller muscles of the shoulder. Happy, healthy practicing! This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. Two common injuries in yoga happen in the shoulder. One is in the front of the shoulder---the biceps tendon---which we will address next time. The other is in the top of the shoulder, called impingement. It happens when the arm lifts up high; the arm bone can bump against the edge of the shoulder blade, called the acromion, and damage the tendon there.

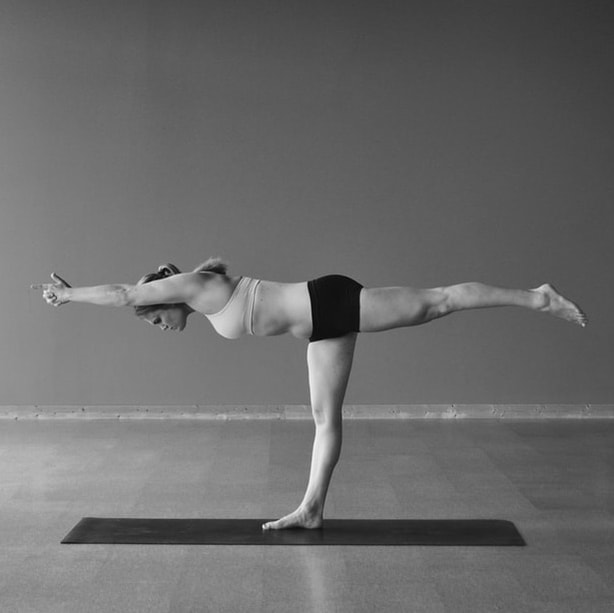

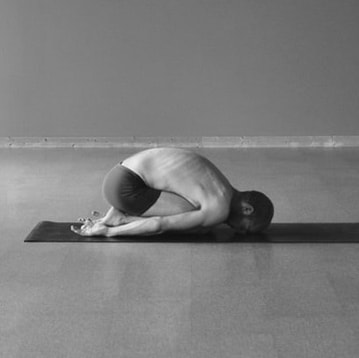

HOW THIS CAN HAPPEN In yoga, this happens most often when we force the arms overhead. Think of any time you link your hands together and then try to straighten your arms using force. As pictured below, it happens in Half Moon Backbend, Half Moon Sidebend, Balancing Stick and Half Tortoise, among others. (It also happens in Downward Facing Dog.) When we force our arms to straighten overhead, we usually use the triceps, a muscle mainly of the elbow, to compel movement in the shoulder. This is where we get into trouble and impingement can happen. You will feel a 'pinching' sensation in the top and outside of your shoulder. This is the bones bumping into each other, damaging the soft tissue. If the shoulders become injured this way, they will be painful whenever lifting the arms sideways, and the breathing exercise pictured at the top will cause pain.  HOW TO HELP The simplest and most effective way to avoid this injury is to not link your hands together. Just place them side by side without interlacing the fingers. Interlacing the fingers and forcing the arms straight overhead is the easiest way to create the injury. Or don't lift your arms overhead (pictured below left). Most postures can be done quite effectively without the arms overhead. All of the positions pictured above don't require the arms to get the primary benefit. Alternatively, you can lift your arms forward and up (pictured below) instead of out to the side. This will help the shoulder blades move into the proper position and keep the shoulders healthy. In the breathing exercise, pictured at the top, you can keep your elbows lower, not lifting them higher than the shoulders. This will prevent further irritation of this area. To build strength in the area, postures like Full Locust will help (pictured below right). By pulling the shoulders back and together, we build strength in the back of the shoulder to help stabilize and balance the joint. CONCLUSION

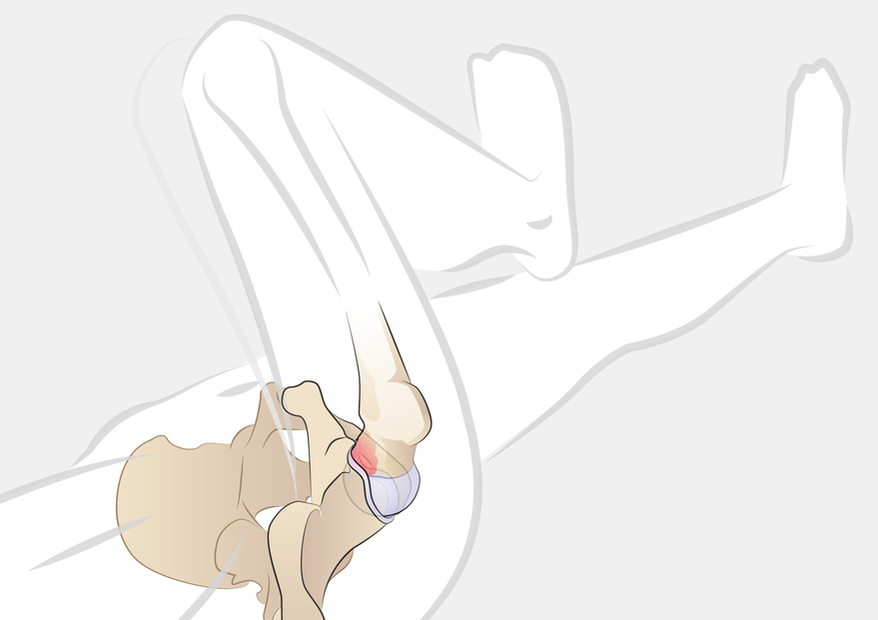

The moral of the story is that we should be aware and careful when lifting the arms overhead, especially if we are gripping the hands together and straightening with force. If there is a 'pinching' sensation in the top of the shoulder, back off immediately. There is nothing there to 'stretch', and it is likely that we are impinging our supraspinatus tendon. Try adjusting your approach to the posture and using your shoulders a little differently. Happy, healthy practicing. This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. The second most common injury we see in the yoga world is of the hip. The damage happens when the hip bends (flexes) significantly. The thigh bone can bump against the bone of the pelvis and hip socket, crushing the cartilage there. This is called hip impingement. The injury generally happens in three progressive stages that may take months or years to develop. In the first stage, there is a slight or moderate pinching sensation as we pull the leg into the chest or rest the body onto the leg with gravity. This pinch is not the result of muscular engagement or tissue stretching, but of bone resting on bone and squishing the cartilage between. (There is a somewhat common instruction to 'feel a pinching sensation in the hip' in some postures. We recommend against this, for obvious reasons.)

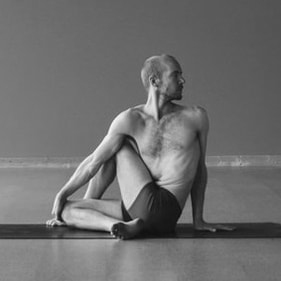

If we continue to damage the cartilage beyond the second stage, in the third stage it can actually tear and pull away from the hip socket. This is called a labral tear, because the cartilage ring around the hip socket is the labrum. This injury can be quite painful, making it excruciating to do something as simple as walk. Like in the second stage, not only will the hip joint itself hurt, but the muscles of the thigh will struggle to function properly. Common postures that are in danger of causing this injury are those that involve deep hip flexion, which is bending of the hip joint. These include Wind Removing (pictured above), Bikram Triangle, Standing Bow, Half Tortoise, Separate Arms Balancing Stick and Spinal Twist (Ardha Matsyendrasana). Look at the position of the hip in all these postures. Notice that the deep flexion can cause the thigh bone to bump into the pelvis. How can we avoid, prevent or heal this injury? As with most things, prevention is the most effective method, as it will keep the body healthier and pain-free. To prevent this injury, pay close attention in any of these postures where your hip is deeply flexed. If you feel a pinching or pressure in the top/front of your hip, back off a bit. It can be challenging to separate this sensation from a stretching or engaged muscle, but the differentiation is quite clear once you notice it.

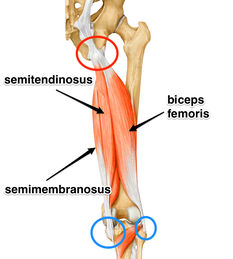

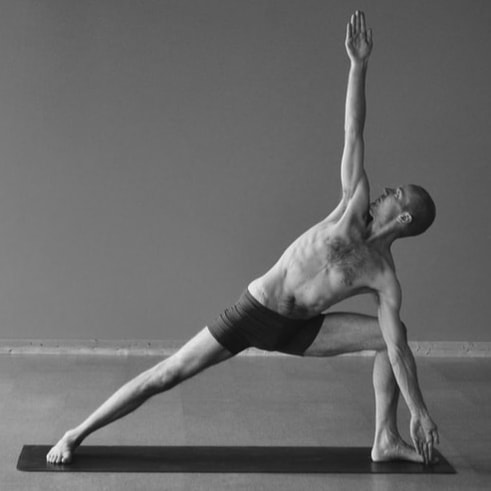

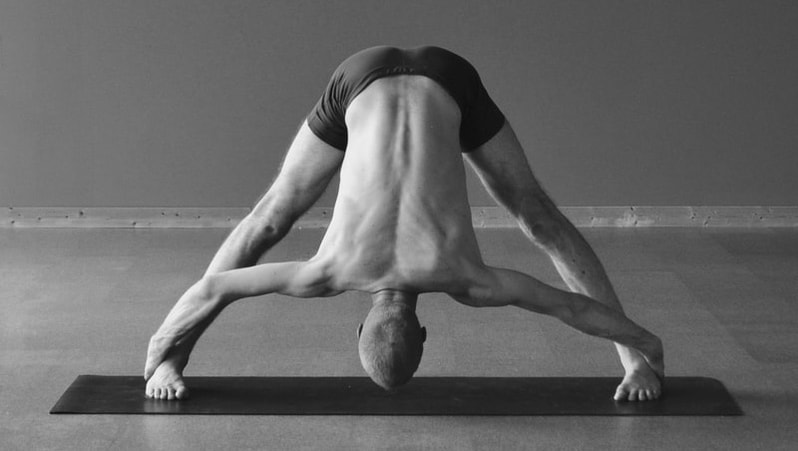

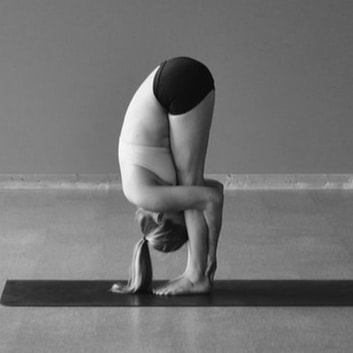

Anytime we use the arms to pull the leg deeper toward the pelvis, use great care! This is taking the hip joint past its normal range of motion, and is a common way to injure the hip. In most (perhaps all) situations, pulling will increase the risk of injury. Healing damaged hip cartilage is difficult. If you are only in Stage 1 or Stage 2, backing off of the postures will likely allow the body to heal. You will need to be conservative with the hip for awhile, at least six weeks. If you have a torn labrum, the conversation gets more complicated, as most will recommend surgical repair. The cartilage doesn't have a great blood supply, so it has trouble healing on its own. There are some stories of non-surgical success, but they are few and far-between. For us, the moral of the story is to be careful and gentle. Most people practice yoga to improve their health, and injury is the exact opposite of that.  This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. The single most common injury that we see in the yoga world is a hamstring attachment injury. It happens due to over-stretching the hamstrings. Since so many postures and exercises target this muscle group on the back of the thighs, what often ends up happening is we over-stretch and the tendon that attaches the hamstrings to the sit bones gets damaged. Quite often, we mistake this new, intense sensation for a "deeper" hamstring stretch, so we continue to push (or more often pull). This makes it worse, and many of us don't realize there is an injury until serious damage has been done. Stretching the hamstrings has become central to many styles of yoga. Like many other physical elements of modern practice, this emphasis comes from gymnastics, contortion and dance. In any given class, we may stretch the hamstrings from numerous positions: standing, seated, legs together, legs split, one leg, both legs, etc. This injury creates pain at the point where the hamstrings attach to the sit bones (ischial tuberosities), at the base of the pelvis in the back, pictured to the right and circled in red. It can be painful in forward folding positions, and may be sore after class so that it hurts to sit down. It is sometimes called "yoga butt". This injury is so common that almost half of yoga practitioners---men and women---have it currently or have had it in the past. Common postures that could strain the hamstrings are: Hands to Feet, Standing Separate Legs Stretching (pictured above), Standing Bow, Standing Splits, Stretching, Separate Legs Stretching and Tortoise, etc. Take a moment to notice the similarities in these positions, pictured below. They all tilt the pelvis forward with relationship to the femur (thigh bone). This makes the hamstrings long, which is why we feel the "stretching" in the back of the leg. The deeper these postures are, and the harder we push them, the more likely it will be to damage the attachment of the hamstrings. HOW TO HELP

First and foremost: rest. I know you don't want to hear this, and resting can be a real challenge for the mind and ego. This injury can take months or years to heal, and the more we aggravate it the longer it will take. Avoid forward folds for several months. Seriously! You can still do lots of other exercises and postures, but avoid forward bending of the hip for awhile. DO NOT STRETCH YOUR HAMSTRINGS! Second, don't overstretch the hamstrings, even after you're healed. The natural range of motion of the hamstrings only gets the femurs (thigh bones) to about 90 degrees with the pelvis when the knees are straight. This means that the vast majority of contortion-influenced yoga postures that "stretch" the hamstrings take it too far, which is why injury is so common. You might not be able to do Standing Splits with the same picturesque beauty, but you will be able to walk and sit without pain. Third, strengthen and shorten the hamstrings. We did a whole blog on this, where we explain a handful of postures and exercises that will make the legs strong and help prevent injury. These include Balancing Stick, Squatting, Bridge and Jastiasana. IN CONCLUSION The most important thing to take away from this is that you can get hurt from yoga practice. If you have pain at the back of your hip, the top of your hamstrings, at or near your sit bones, and this is exacerbated when you do forward folding postures, STOP IMMEDIATELY! It is very likely that you are damaging the upper attachment of the hamstrings. Take the time to let it heal, and then perhaps adjust your approach to the physical postures so that they have less likelihood of injury. Over the past few months, we have heard increasingly loud calls for talk about injury in yoga. So many students are hurt or have pain, and they don’t know what it is, how it happened or how to fix it. Some are even told by their teachers to push through the sensation to continue deepening the physical postures. After all, these exercises and postures are supposed to be healing, right? When we describe the common yoga injuries, students are both 1) shocked that you can get hurt doing yoga, and 2) surprised to hear us describing the pain and difficulty that they experience.

Yes, yoga can hurt you. It’s true. If you’ve practiced the physical forms of yoga that are popular in the West for more than a few months, chances are you’ve been injured or know someone who has. This is not to say that physical yoga practices are inherently dangerous or should be avoided. The same risk is present in virtually any physical activity: basketball, running, bowling. Anytime we use the body in a repetitive way and push it to go farther and farther, the risk of injury is quite high. We generally don’t know the limits of our capabilities until we go too far! Yoga is mostly thought of as a healing, healthy and therapeutic form of exercise, not to mention safe. Since most of us approach the practices thinking they will help us, we overlook the possibility for injury until it’s too late. It is especially true in the yoga world, where we want to believe that it only has the ability to make us better, more open, happier, peaceful versions of ourselves. The idea that any of these practices could injure our bodies, nervous systems or minds feels foreign and even contradictory. So all too often we disregard it. Until we get injured. Even then, we may think it was our fault, that we weren’t doing the practice right, because a “healing” practice couldn’t possibly be dangerous. But injuries are quite common in yoga. And each style has its own tendency toward certain imbalances, as the stress and repetition in each practice are a little different. We are going to do a whole series of posts about Injuries In Yoga. We will go into some depth about the most common injuries we see, which include hamstring attachment strain, hip impingement and labral tear, meniscus tear in the knee, supraspinatus damage in the shoulder, bicep tendon strain in the shoulder, sacroiliac instability in the low spine, and neck pain in the base of the neck. All of these can be created or exacerbated by physical yoga practices. For now, we want you to know that yoga can injure you, especially if you think it never will. Always take care and try to understand what you’re doing and why. Some intense sensations are safe and even beneficial, while others are not. Use caution and ask your teacher if you’re not sure. If they tell you that you won’t hurt yourself in yoga, get a new teacher. If you have an injury or had one in the past that you’d like to tell us about, please comment or message. Let us know your experience! Almost every yoga practitioner who has been at it for more than a few months has dealt with an injury. The physical nature of our western yoga practices---the deep stretching and vigorous movements---is bound to injure the body sooner or later, just as any physical activity carries the danger of bodily harm. Lots of us even start a yoga practice to help deal with preexisting injuries.

The point is that injury is common among practitioners of yoga, and contrary to how it may seem, injuries are actually invaluable for the progress of our practice. CARRY ON, MINUS THE EGO Think about it: how do you deal with an injury? After an initial period of frustration and even anger, you slow down and figure out how to carry on with the new reality. This "carry on" mentality means we have to let go of who we thought we were before and adopt a new mentality of who we are now. This is a crushing blow to the ego, which holds on tightly to our idea of the self. Believe it or not, this is a profound step in the yogic practice: learning to detach from the belief that we are our body or the postures we do. ATTENTION INWARD The next thing you do is continue your practice (hopefully), but with an intense inward focus. Your awareness of the body is heightened by your pain and the desire to heal. This heightened bodily awareness is one of the highest goals of physical practice. By turning our attention inward, we recognize what the body is (a body) and what it isn't (the self). From there, the progression toward detachment continues. HEALTH Of course, we are not suggesting that you go out and hurt yourself. Nor are we suggesting that you practice in a cavalier way that courts injury. These steps of awareness and detachment can happen without injury, too. Also, most of us here in the west practice physical yoga to improve our health. This is wonderful, and health is wonderful. But, yogically speaking, there is always the danger of identifying the "self" with the body. This happens especially when we are strong and healthy. The ego loves to equate itself with physical strength. We hope that you never get injured. But, if you do, remember that your yoga practice and your "self" are not defined by which postures you can do. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed