|

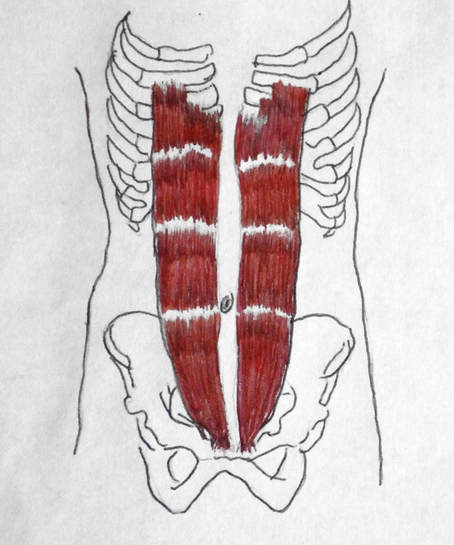

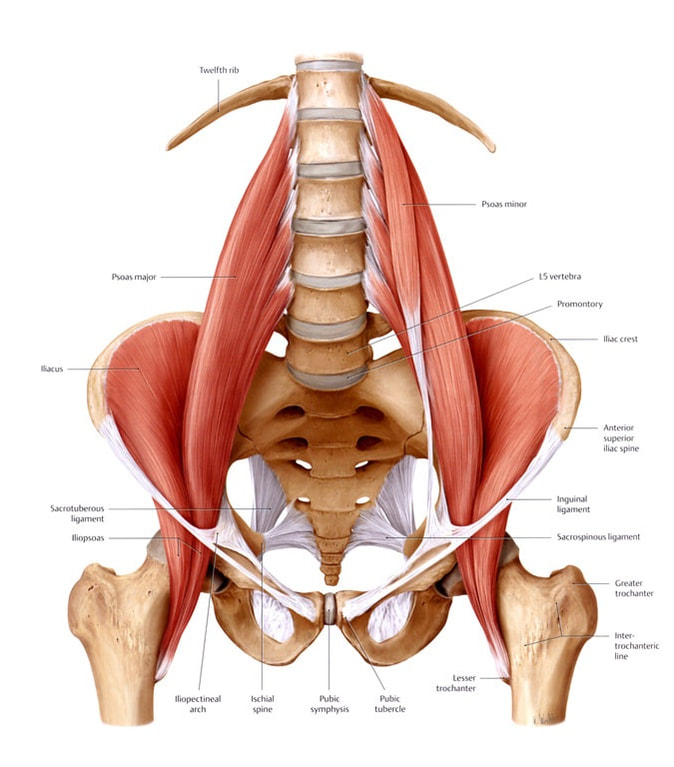

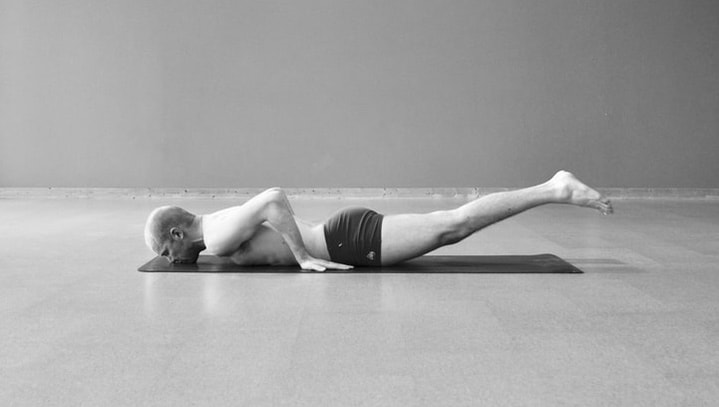

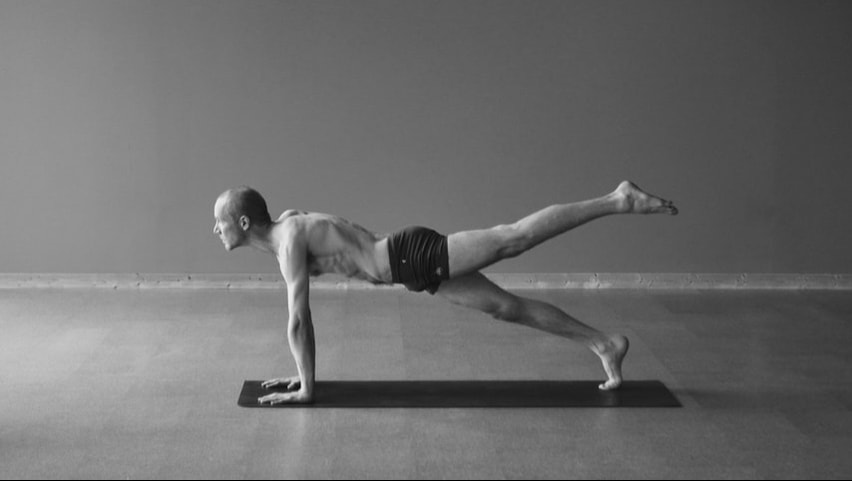

The Sit-Up that we often do in this lineage of yoga - starting flat on the back with the arms overhead and legs straight, then sitting all the way up and touching the head to the knees - is more complex than it looks. It requires strength in two major muscle groups: those of the abdomen, specifically the rectus abdominis (6-pack) and the psoas, which crosses the hips.

INHALE OR EXHALE

The question often arises, "should I inhale or exhale while doing a sit-up?" The answer is clear: You should exhale. In a recent New York Times article about the remarkable abs of USA olympian Adam Rippon, Rippon's trainer Steve Zimm said, "Breathing is everything when it comes to abs. If you want ripped abs, you need to allow them to contract. Before every move, breathe out. Pull your belly button into the spine and continue breathing out as you’re contracting, so your abdominal wall is sinking into you." Not surprisingly, Bishnu Ghosh agrees. In his book Yoga Cure he instructs: "Start from lying position with arms stretched beyond your head, exhale and hold your breath and then raise your upper body..."

6 Comments

This verse from the yogasutras is one of the easiest to understand, and one of the most powerful to put into practice. It can seem overly simple to promote qualities such as friendliness and kindness, but it helps to think about what we are replacing with these qualities.

FRIENDLINESS With friendliness we are replacing competition, the sense that each person is an enemy. When we feel that others are our enemies, we isolate ourselves and retreat to xenophobia, the fear and mistrust of anything that is different from us. The more we perceive others as different, the more we fear them. Friendliness, on the other hand, connects us with others. It frees us from fear and allows us to see more clearly. Sure, there are people in this world to fear and mistrust, but most people are just like us. Cultivating friendliness opens us up to the possibility of growth, connection and change. KINDNESS With kindness we are replacing selfishness and mistrust, both of which lead to meanness. No one wants to be "mean", it is a product of our own fear of not having enough or not getting our due. When we perceive others as infringing upon our rightful space, credit, food or work, we act meanly toward them. To a yogi, the big problem with being mean is that it affects us more than it affects others. It plants seeds of anger, fear and animosity within us, and those seeds will bloom eventually. The more we cultivate meanness, the more we poison our own minds. Kindness is a wonderfully simple way to combat this situation. Treat everyone with kindness, not just those who deserve it. By doing so, we plant seeds of generosity, openness and love, and those seeds will bloom too. INDIFFERENCE TOWARD HAPPINESS, VICE & VIRTUE The final instruction of this verse is more complicated. Why would we want to be indifferent toward happiness? Or vice? Or virtue? According to the yogis, some of the roots of our suffering are our attraction to pleasure and our aversion to pain. These are called raga (attraction) and dvesha (aversion). We enjoy the pleasure that we get from a compliment, attention, success, new shoes or a text message, and we become attracted to that pleasure. Our thoughts and actions are soon directed toward repeating the pleasure, and our existence begins to feel empty whenever we are not experiencing pleasure. For this reason, the yogis say that even pleasure is pain. Once we realize that pleasure and our attraction to it actually brings us more suffering, we begin to detach from the attraction. Gradually we become indifferent toward the ideas of happiness and sadness, pleasure and pain, and vice and virtue. This process takes a good teacher and a long time. How do I make my life simpler? And how do I become and stay humble? These are two questions that keep popping up in my own life, so I struggle with them on a daily basis.

Simplicity is the easier of the two questions, I think. I just have to remove the extraneous bits at the periphery of life: the 2nd and 3rd hobbies; the storage closet, basement or unit; all the outfits; the toys (like an iPad) that I thought would be useful but turn out to be worthless. This is a lot easier when I feel strongly about my purpose in life. I can keep the things that make it possible for me to do my work, and remove the things that are unrelated. My life becomes a little more streamlined, and I am empowered to do the work that is important to me. Humility is tougher because it is internal, and it changes with every bit of knowledge that I gain and every interaction I have. It even changes depending on how my day goes and how I'm feeling. Some days I feel invincible and humility goes out the window. Some days I feel worthless and humility comes all too easily. In some ways, humility gets harder as we learn more. Our knowledge grows, our abilities grow, and it is easy for the ego to grow too. "I am so smart, I am so talented." In other ways, learning, teaching and practicing make humility easier. For each bit of knowledge that I grasp, 3 more bits are revealed that escape my understanding. So the more I learn, the more I realize that my knowledge is a tiny, tiny bit of existing knowledge. Spiritually, the more I practice, the more I realize the true nature of my power, which is to say, it is very small. Inner practice reveals myriad forces in the universe which are far grander than me. This makes humility easy as practice progresses. ALWAYS SEEKING I am always on the lookout within myself for the demise of simplicity or humility. These are the first signposts on the road to corruption and ego-driven existence. They are moving targets, since circumstances are always changing. They need to be constantly monitored. As a teacher, there are few skills more useful than the ability to modify postures to fit the needs of an individual student. In sheer value it rivals the ability to lead a class, but modification requires significantly more knowledge and patience. After all, each classroom is filled with individuals who have different strengths, weaknesses and injuries.

THE PURPOSE OF THE POSTURE Modifying any yoga posture or practice requires two things. The first is knowledge of the posture: What is its purpose? What are we trying to accomplish through its practice? Second is understanding how to adjust a posture to bypass a student's injuries and limitations while maintaining its primary function. Each posture is nothing more than the sum total of its benefits. Does it build strength, flexibility, massage the intestines, affect the blood pressure, etc? Each posture has a unique combination of benefits that defines its purpose. To know these benefits is to understand the posture. Of course, some benefits are more important than others. In general, benefits to the spine, torso, abdomen and circulatory system are more important than the extremities like the arms and legs. Coincidentally, many of the limitations that yoga students have are in their extremities: knee replacements, tight shoulders, painful feet, shaky balance. This means that we can often improve a student's ability to execute (and therefore obtain the benefits of) a posture by removing the extremities and focusing on the center. This week I picked up Time Magazine's "The Science of Exercise" special issue, as it promised to illuminate the most recent discoveries in movement and health. It is interesting to think about what this means for the future of yoga practice. I recognize that yoga is traditionally not an exercise regime, but it has become quite physical over the past 100 years, to the point that it now fills the fitness quota in many people's lives.

Exercise Will Become More Individualized and Prescriptive As the medical community recognizes the preventive value of exercise, it will be recommended more to patients of all ages, both to combat disease and to prevent it. Physical activity reduces the risk of heart disease, many forms of cancer and several mental disorders like depression. In the future, each person will be assigned or "prescribed" a different exercise regime based on their health, ability and needs. This is not unlike the method of prescriptive yoga that has been in India for hundreds of years. "Young and old," wrote Bishnu Ghosh in 1930, "there is a different exercise for each of you--an experienced trainer can only rightly select them." Lifting Weights Is Important For Strength and Health Muscular strength and bone density are two important factors in keeping us healthy and pain-free. Weak muscles lead to imbalance, injury and painful joints. Keeping our bodies strong, especially around the spine, hips, knees and shoulders reduces the risk of injury as we age. Keeping the bones strong is also important, reducing the likelihood of breaks. Both of these things are improved by lifting weights. Thus, weightlifting should be a regular activity for pretty much everyone. Yoga exercises increase strength to a certain degree, using the bodyweight as resistance. More often, though, yoga practices are focused on flexibility at the expense of stability and strength. Our overall health will be better served if we focus at least part of our physical practice on strength. Flexibility is useful when it restores functional range of motion to stiff joints, but it can also be detrimental when pushed too far. A balanced practice of flexibility and strength, even including weight lifting, will be more effective in keeping us healthy in the long term. The Bhagavad Gita is one of the primary sources of Indian spirituality. It is one of the three sacred texts of Vedanta, along with the Upanishads (the last books of the Vedas) and the Brahma Sutras (an explanation of the Upanishads). Vedantic philosophy argues that all of the universe is a manifestation of a single, infinite consciousness called Brahman. Out of Brahman come all people, places and things. Only Brahman is real and permanent. This is the belief of Advaita (Non-dual) Vedanta.

Within the Bhagavad Gita are explanations of many different "yogas." 17 of the 18 chapters have the word "yoga" in the title, with each chapter expounding on a different one. These range from Samkhya Yoga to Karma Yoga and Bhakti Yoga, not to mention other more complex ones like Raja-Vidya-Raja-Guhya Yoga. This abundance of seemingly different "yogas" can lead to confusion. Are there dozens or hundreds of yogas? Is there a unifying philosophy or belief that one can point to as yoga? According to Vedantic belief, since all beings and existence are manifest from a single consciousness, this diversity is possible even within a single entity. One can choose any form of devotion and even express devotion to diverse "Gods," all of which are nothing more than the many names and forms of Brahman. The great diversity exists within a single consciousness. This philosophy is not to be confused with the yoga of the Yogasutras by Patanjali, a system based on the Samkhya philosophy. Samkhya philosophy is dual, believing that two independently real entities exist: consciousness and matter. These are called purusha and prakriti. Vedanta is a monistic philosophy while Yoga (of the Yogasutras) is dualistic. As we practice yoga, we strengthen our energy. As we feel better, we have a greater desire to be active. We may take on more tasks, teach extra classes, volunteer or be of service. All of these are and can be positive contributions to the world, but there is danger in beginning to draw these actions toward the self. We may start to have thoughts like, "Look at all this energy I have! Look how much I can accomplish!"

While this may be true on the outside, it's more complicated on the inside. As we feel stronger and more energized, it becomes increasingly important for us to find devotion as a response to the feelings of "look what I can do!" Devotion means that we offer both the energy we feel that makes action possible, and the actions themselves, to a higher good or a higher power. We can cultivate this through prayer or mantra, and practice it through being of service even in our daily activities and interactions. When we practice yoga and feel more energized, we should understand that this energy is just a result of becoming aware of it. It is not that we created it. Then when we take this energy and put it into action, we can understand that we are in service to the world, as opposed to doing good for the sake of building ourselves up. As a teacher, it is easy for time spent teaching to cut into time that used to be for personal practice, as if both endeavors draw from the same “yoga time.” With this system, as teaching time increases, practice time necessarily decreases. This leads to trouble, because the two are not the same.

Teaching, even though it is rewarding, is a service that draws from our well of energy and strength. Most of us begin as teachers with an overflowing well, so we can continue for some time without noticing, but eventually our work will suffer, we will become repetitive, uninspired and uninspiring. We will be drawing from an empty well. Personal practice fills the well. It inspires and fulfills our curiosity, propelling us forward and directing our progress. The more powerful we want our teaching to be, the more powerful our personal practice needs to be. Otherwise teaching is unsustainable and can even be detrimental to us personally, sapping our energy and will. Not to mention we are not serving our students, which is our most important job. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed