|

INTENTION

The most important element of this posture is the compression of the front side of the body, namely the throat (massaging the thyroid gland) and the belly (massaging the stomach, liver, pancreas and intestines). The goal is to touch the forehead to the knee, but the most important element is the compression. Whatever depth you attain, compress the throat and belly as much as possible. Don’t be tempted to hold your head with your hand and pull it toward your knee. That defeats the purpose of the posture. BREATH With the front-side compression in this posture, breathing is limited. Keep the breath short. Don’t release the compression of the posture to take deeper breaths. Focus on the exhale, using it to shrink the chest and increase the compression of the belly. BENEFITS This posture massages the internal organs, intestines and the glands in your throat, improving digestion and helping to balance the endocrine system—a tremendously therapeutic posture. It strengthens the muscles of the abdomen and stretches the muscles on the back of the spine. It stretches and strengthens the hips and legs. NOTE This posture can be remarkably uncomfortable, especially at first. The low belly is an area of the body that is often neglected and weak. This posture tightens and massages the low belly, creating movement in the intestines that can cause nausea. Don’t let the discomfort deter you from earnest practice. This posture is very beneficial and unique to the Ghosh lineage of yoga. Excerpted from the Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual - Beginning.

0 Comments

In the first text that describes Hatha Yoga, the Dattatreyayogashastra (DYS), there are two separate systems of "force" (hatha) that can be used. The first system is the ashtanga system, with 8 parts that coincide with Patanjali, Yajnavalkya and others.

The second system is "the doctrine of adepts such as Kapila." (DYS, 131) This second system is a set of 9 mudras, practices "that assist in the preservation and raising of bindu, the essence of life, either through mechanical means or through the raising of the breath through the central channel." (1) Over the centuries, the original system of bindu-raising got overlaid with "the visualization of the serpent goddess Kundalinī rising as kundalinī energy through a system of chakras." (1) By the time of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP) a few hundred years later, the stated goal of the mudras was to raise kundalini. (HYP 3.5) The mudras (seals) described in the Dattatreyayogashastra include mahamudra, mahabandha, mahavedha, khecharimudra, jalandharabandha, uddiyanabandha, mulabandha, viparitakaranam and vajroli. THE MUDRAS Mahamudra: The "great seal" executed by placing "the heel of his left foot at the perineum. He should stretch out his right foot and hold it firmly with both hands. After placing his chin on his chest he should then fill [himself] up with air. Using breath-retention (kumbhaka) he should hold [his breath] for as long as he can before exhaling. After practising with the left foot he should practise with the right." (DYS, 132-134) This mudra has evolved into the common posture Janushirasana, or Forehead to Knee Posture, which is essentially the same physical position done without the retention of breath. Mahabandha: The "great lock" is performed the same as the "great seal" above, but by placing "the outstretched foot onto his thigh," (DYS 135) essentially creating a Lotus or Half-Lotus type position with the legs. Mahavedha: The "great piercing" is done "while in the great lock" by tapping the buttocks on the ground. (DYS 136) Khecharimudra: The "sky-roving seal" is achieved by turning the tongue back, putting it above the soft palette and holding it in the nasal cavity "in the hollow in the skull while looking between the eyebrows." (DYS 137) Jalandharabandha: The "jalandhara lock" is done by constricting "the throat and firmly plac[ing] the chin on the chest. It prevents loss of the nectar of immortality (amrta)" from dripping from the skull into the fire of the abdomen. (DYS 138-141) Uddiyanabandha: The "uddiyana lock...is easy and always taught because of its many good qualities...With special effort [the yogin] should pull his navel upwards and push it downwards." (DYS 141-142) It is unclear from this instruction how the breath is to be held. Mulabandha: To achieve the "root lock," the practitioner should "should press his anus with his heel and forcefully contract his perineum over and over again so that his breath goes upwards." (DYS 144) Viparitakaranam: The "inverter," turning the body upside down, is said to destroy all diseases. "On the first day the head should be down and the feet up for a short while...He who regularly practises for three hours is expert at yoga." (DYS 148-150) Vajroli: Vajroli "is a great secret," done by literally preserving the semen. "If the semen moves then [the yogin] should draw it upwards and preserve it." (DYS 155-156) It is worth noting that these techniques have been mostly abandoned by modern western yoga. Mahamudra has been appropriated as the posture janushirasana. And the three locks---jalandhara, uddiyana, and mula---have been adapted and used for other purposes. Their modern instruction is quite different than in this text. This system of Hatha Yoga is largely forgotten. 1. Mallinson, James. Hatha Yoga entry in Vol. 3 of the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism While the standing postures in Bikram's yoga class---in all of yoga---are mostly less than 100 years old, the 2nd half of class that happens lying and sitting is mostly filled with traditional positions from old texts of hathayoga. 8 of the 13 postures in the 2nd half of Bikram's class are from traditional hathayoga texts.

We looked at the three best-known texts of hathayoga: the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP) from about 1500, the Shiva Samhita (SS) from about 1500 and the Gheranda Samhita (GS) from about 1700. In the standing section of Bikram's class there are two old postures: utkatasana (GS 2:27) and tadasasana, which was originally called vrikshasana (GS 2:36). Below are the postures in the second half of Bikram's class, followed by the traditional texts in which they are instructed. Pavanamuktasana (not in these texts) Bhujangasana (GS 2:42) Shalabhasana (GS 2:39) Purna Shalabhasana (not in these texts) Dhanurasana (HYP 1:25, GS 2:18) Vajrasana (GS 2:12) Ardha Kurmasana (not in these texts) Ushtrasana (not in these texts, though there is a posture called ushtrasana in GS 2:41 done on the belly and grabbing the ankles) Shashangasana (not in these texts) Janushirasana (this position was called mahamudra in SS 4:25-36 and GS 3:4-5) Paschimottanasana (HYP 1:28-29, SS 3:109-112, GS 2:26) Ardha Matsyendrasana (HYP 1:26-27, GS 2:22) Shavasana (HYP 1:32, GS 2:19) It is worth noting that all 8 of the postures, plus the 2 in the standing section, are in the Gheranda Samhita. This text was written in Bengal, the eastern Indian province where Kolkata (and Ghosh's Yoga College) is located. It seems that this text was instrumental in the development of yogic culture in the Bengal region. How old does a posture or practice need to be to be considered "traditional?"

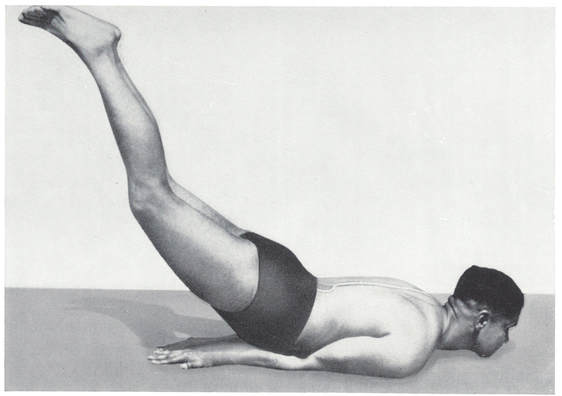

Is it traditional if the practice was originated in the 1970s? The 1950s? The 1930s? Is it traditional if the practice was originated in the 1700s? The 1500s? The 1200s? Perhaps just as important: Does it matter if practices are traditional? "The Locust Pose has the same health effect as Bhujangasana [Cobra Pose]. However, it emphasizes the lower parts of the spine, the sacrum and the hips. You could call this Purna-Bhujangasana (Full Cobra Pose). Some experts are of the opinion that after practicing Bhujangasana twice one must practice Shalabhasana once. Others say practice Bhujangasana one week and then one week of Shalabhasana." (p.37)

From 84 Yoga Asanas by Dr. Gouri Shankar Mukerji. INTENTION

Easy Posture is the first and simplest of the Lotus postures—seated, cross-legged posi- tions that are used for breath control and meditation. The most important part of this posture is making the spine and pelvis upright. An upright spine enables an open and relaxed chest for breath exercises and an aligned nervous system for meditation. BREATH Breathe deeply and slowly in this posture. BENEFITS The physical benefits of this posture include rotation in the hips, flexibility in the legs, knees and ankles, and strength in the pelvis, abdomen and lower back. Exerpt from the Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual - Beginning Most of us desire to be healthy and live a long life. Many of our cultural institutions and fads are centered around these ideas: health food, exercise, health care, etc. Beneath it all, a deeper question is easily ignored. What is the purpose of being healthy or living a long life? (This can be reframed as the age old "what is the meaning of life?" question, or the "why are we here?" question.)

If we don't address this question directly, we end up essentially spinning our wheels. Without a greater sense of purpose, health and long life become the goals themselves, and we start pursuing them for their own sake. We even start admiring those who are very healthy or who have lived a long time. OVERCOMING DISEASE Admittedly, it is difficult to pursue anything when we are ill. Patanjali lists disease as one of the 9 obstacles that distract our thoughts from higher purpose. (Yogasutra 1:30). When we are ill, we have little concern other than to regain our health. But when we are healthy it is important to turn our efforts toward other goals. Our health facilitates our pursuit of higher purpose, and we should be careful that our health or fitness doesn't become the primary focus of our existence. THE WILL TO LIVE The desire to live a long life is inherent in our culture and medical system. One of the primary measures of a "useful" medicine is whether or not it increases lifespan. If not, or if it decreases lifespan, it is often consigned to the trash heap. According to the Yogasutra, one of the five forces of corruption is "the will to live." (YS 2:3) If we are afraid of dying, (which to be honest, nearly everyone is) then the ultimate goal of life is simply to stay alive. It is almost impossible to pursue a higher purpose. "The will to live is instinctive and overwhelming, even for a learned sage," Patanjali writes. (YS 2:9) Our life is not useful in itself. It is only useful as far as it enables us to accomplish other things. What is your purpose? It is normal to not have an answer to the question. Humans have been asking it for as long as we have existed. But it is a question worth asking. This past Saturday we kicked off the fall season with a workshop at the inaugural Harvest Moon Yoga Festival in rural Wisconsin. It was a beautiful day of sun, yoga and music. The next two months are full of workshops around the US and Canada. Maybe we will see you!

Being yoga teachers is a great joy, honor and responsibility. Students spend their time, money and brain-power when they are with us, and we try to repay it with the highest level of information and experience we can. We love being with everyone in our workshops. All the questions, curiosity, intelligence, bodies, struggle and earnest effort are challenging and inspiring. If you are a yoga student, we hope you approach your practice with curiosity and passion. If you are a yoga teacher, we hope you find inspiration and joy in your work, and that you instill the same in your students. Have a great fall! We hope to see you! INTENTION

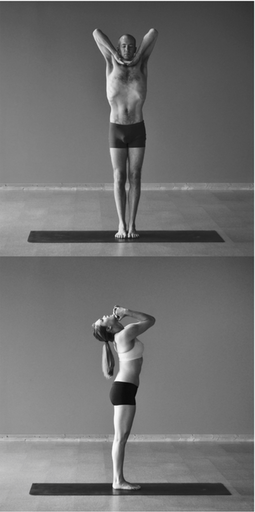

This exercise deepens the breath, expands the lungs and strengthens the breathing muscles in the chest. Use the lifting arms to stretch the ribs wide and help the lungs fill completely. Pull the belly in at the end of the inhale; it helps to isolate the muscles in the ribcage, making them stronger and opening the lungs. On the exhale, as the head drops back, stretch the chin up and away to get an even bend in the neck. The natural motion of the torso on an exhale is to contract. By extending the throat here we create tension and build heat in the body. Work to slow your breathing down. As a beginning student try for four to six seconds on both the inhale and exhale. As an intermediate try for eight, and as an advanced student ten. Start to develop the connection between breath and physical movement. It will bring about calmness and steadiness in your postures. Notice your body calming and thoughts slowing down as you progress through the exercise. Notice your focused and present state of mind. Learning simple breath control techniques like this can be used in stressful or emotional situations in your daily life. BENEFITS Any exercise that slows the breath will slow the heart rate, lowering the blood pressure and reducing stress. This exercise increases lung capacity and strengthens the breathing muscles in the chest. It also stretches the shoulders, hands and throat. Excerpt from the Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual - Intermediate This post draws from, paraphrases and is inspired by Gregor Maehle's post from a few days ago.

In the foundational text about yoga, Patanjali's yogasutra, yoga is defined and then explained. The twelfth sutra says that "cessation of the turnings of thought [the defined purpose of yoga] comes through practice and dispassion." Maehle translates the last word of this sutra ("dispassion") as "disidentification," a subtle difference that has important philosophical repercussions. PRACTICE Practice is not enough, nor is disidentification. If we only practice, our mind develops deep ruts of habit and fundamentalist beliefs that our way is the only way, to the exclusion of all other paths. "If we practise only, then we tend to develop beliefs like ‘Our practice is the only correct practice,’ ‘Only Ashtanga Yoga is the correct yoga,’ ‘Only Mysore style is the correct form for a yoga class,’ ‘Only the God that I worship is the true God,’ ‘Capitalism is the only proper economic system’ and ‘Democracy is the only proper political system,'" writes Maehle. In these examples we can clearly see the power of practice without the tempering effect of disidentification. We come to identify ourselves and the whole of reality through the lens of our own practices, whether yogic, spiritual or political. DISIDENTIFICATION The opposite end of the spectrum embraces "disidentification" without embracing practice, leading to a groundless form of relativism where all views, beliefs and actions are equal. With this relativism come the beliefs that "‘All paths lead to the same goal,’ ‘It’s all yoga,’ ‘Everything is holy and sacred,’ ‘Everybody has to live their own truth,’ Everybody has to do their own thing,’ ‘All statements, philosophies and religions are valid,’" writes Maehle. This is the opposite of fundamentalism, but equally as extreme. You may know people and yogis who inhabit both of these extremes. According to Patanjali, the path to yoga requires a middle path that embraces both of these ideas, practice and disidentification. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed