|

Our recent blog about the myth of oxygenation got a big response. Lots of surprise, some disbelief and a lot of requests for more information. Specifically, if deep breathing does not have a positive impact on our oxygen levels, why do we do it?

There are three huge benefits to practices of breathing: activating and balancing the muscles of breathing, which in turn affects the nervous system; balancing the hemispheres of the brain through the nostrils; and awareness and minor control of the breath-regulating parts of the brain. THE MUSCLES & THE NERVOUS SYSTEM You may have heard that some people are belly breathers and some are chest breathers. Most of us have at least a slight imbalance between the abdomen and chest, while others have extreme imbalance. This doesn’t necessarily have an effect on our ability to get oxygen, but it does have an impact on our nervous system. Generally speaking, abdominal breathing that uses the diaphragm and relaxes the abdominal muscles stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system. The opposite is true for chest breathing that uses the intercostal muscles. This stimulates the sympathetic nervous system. Neither of these is a problem until our breathing patterns become imbalanced and we breathe primarily through only one of the systems. When years or decades go by, one part of the nervous system chronically gets stimulated while the other gets suppressed. Belly breathers will be more relaxed, sleep more, have lower body temperature, be more lethargic. Chest breathers will be more energetic, more stressed, warmer, sleep less. It is vital for progress in yoga to have balance in the nervous systems. So the first step of breathing practice is to learn to use both parts of the breath, strengthening the muscles and evening the nervous systems. BRAIN HEMISPHERES The olfactory nerves in the nose go straight to the brain. They have the most direct connection to the brain of any of the senses, so their stimulation through the nostrils is potent. The breathing practice of Alternate Nostril, which goes by many names, is one of the oldest yogic techniques. By alternating which nostril we breathe into, we vary the hemisphere of the brain that we stimulate. This has a further effect on the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and goes even further to balancing the dual nature of the body and mind. PARTS OF THE BRAIN The breath is controlled by the brain stem, the oldest part of our brain. Most of the time, we breathe with no conscious thought. But the newer parts of the brain, specifically the cortex, have the ability to override the brain stem to some extent, especially with practice. This awareness and control is very difficult and not appropriate for beginning practitioners, but it is the ultimate reason for breathing practices. Gradually we come to realize the true nature of the breath, which brings us closer to realizing the true nature of the self. (Apologies for the abstract yogi talk, but I don’t know of a clearer way to put it.) IN CONCLUSION So breathing is powerful. If we use it correctly it has the ability to balance our nervous system, the hemispheres of the brain, and even put us in touch with some deep and essential parts of our being. To me, this is all way more exciting than oxygenating the body!!

1 Comment

The Gheranda Samhita, written in around 1700 C.E., is the most encyclopedic of the hathayoga texts. It was likely composed in the Bengal region of India, the same region that houses Kolkata and Ghosh's College. This text was available in Bengali, a regional language spoken by ordinary people, as opposed to the sacred Sanskrit, so it had an outsized impact on yoga's development in the last few hundred years.

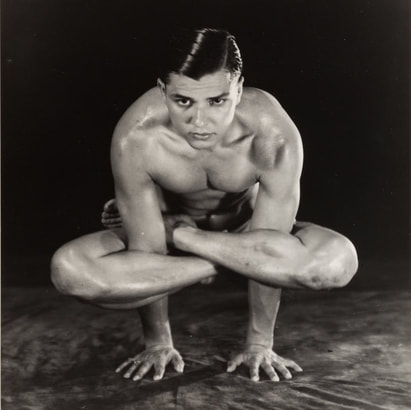

84 ASANAS The idea of "84 Asanas" is prominent in Ghosh's lineage, with Buddha Bose (1930s), Gouri Shankar Mukerji (1960s), Tony Sanchez (current) and Esak Garcia (current) either designing systems around the number or drawing symbolic attention to it. The concept is prominent in the Gheranda Samhita. The second chapter, on Asanas, begins: "All together there are as many asanas as there are species of living beings. Shiva has taught 8,400,000. Of these, 84 are preeminent, of which 32 are useful in the world of mortals." The text goes on to describe and instruct those 32 asanas, by far the most in any hathayoga text. 23 POSTURES IN COMMON Of the 32 postures in the Gheranda Samhita, 23 of them are taught by Ghosh and his disciples. These include simple postures like Bhujangasana (Cobra Posture) and complex ones like Kukkutasana (Rooster Posture, pictured above). They include postures that were taught in the early days by Bose and Mukerji but have been lost to modernity, like Mandukasana (Frog Posture), and ones that are nearly ubiquitous in all yoga lineages and styles, like Dhanurasana (Bow Posture). Many of the postures that are no longer practiced are variations of sitting, with the legs crossed in specific ways, the hands held with detail, or specific focus of the eyes. These postures have diminished in modern times as the practice of yoga grows more athletic and physical. MUDRAS, PRATYAHARA & PRANAYAMA The last few chapters of the Gheranda Samhita cover topics that have largely been lost to modern western iterations of yoga. Admittedly, they are often difficult and require significant effort and persistence. In Ghosh's lineage, the practice of pranayama has been whittled down to Kapalbhati, with Sitali offered to some advanced students. Mudras and Pratyahara are more advanced still. It is impossible to read the Gheranda Samhita without seeing the resemblance to what has been passed down by Ghosh and his students. We all have a dilemma each time we open our mouths to speak. Do I say what I know or do I ask about what I don't?

We may say what we know to express our opinion in a conversation, to convince, to teach or simply to reinforce our own reality by saying it out loud. As yogis, we should be careful of this. Every time words come out of our mouths, their reality is solidified in our minds, and we become more rutted in our version of things. When we ask what we don't know, two important things happen in our minds. We acknowledge that we don't know everything, a humility that is absolutely essential for growth and human connection. And we open ourselves up to new information and knowledge. How will we get smarter and better, how will we make progress if we think we are at the pinnacle of knowledge and understanding? This is why I love to be wrong and to admit that my knowledge is incomplete. Only during these moments can I learn new things and make progress in understanding. This benefits me by making me smarter and more complete, and more so by maintaining humility and flexibility in the "reality" that is my mind. How many times have you heard a yoga teacher tell you that deep breathing "oxygenates the blood?"

It isn't true. At the very least it is misleading. Our nervous system forces us to breathe at the necessary rate to fully oxygenate our blood at all times. This is true when we're resting as well as when we're running a marathon. The body's oxygen requirements are different depending on our activity, and the nervous system automatically adjusts to oxygenate the blood fully. Normal blood oxygenation is 95-100%. When we are at rest, we breathe slower since the body's oxygen demands are less. Breathing more or deeper while the body is at rest does not "oxygenate" the blood. It hyper-ventilates, which is just a way of saying breathing (ventilating) more than necessary. Anytime we breathe more than the body requires, the big change we are causing is the removal of carbon dioxide, one of the body's metabolic wastes. Hyperventilation removes more carbon dioxide than the body produces, and this leads to a whole host of physiological effects. Most significantly, the blood vessels in the brain constrict, limiting blood flow to the brain. This makes us light-headed. So that light-headed feeling you get when breathing deeply isn't energization or "oxygenation," but constricted blood vessels in the brain. Your brain is actually getting less oxygen than if you were to breathe normally! The muscles of the body most often use concentric contraction to create movement. This means that a muscle shortens as it contracts, pulling the skeleton into position. For example, in backward bends the erectors of the back contract and shorten, and the spine bends backward. In forward bends, the rectus abdominis (6-pack) shortens and contracts to bend the spine forward. This type of contraction is also how we walk, run, stand up and do many other basic functions.

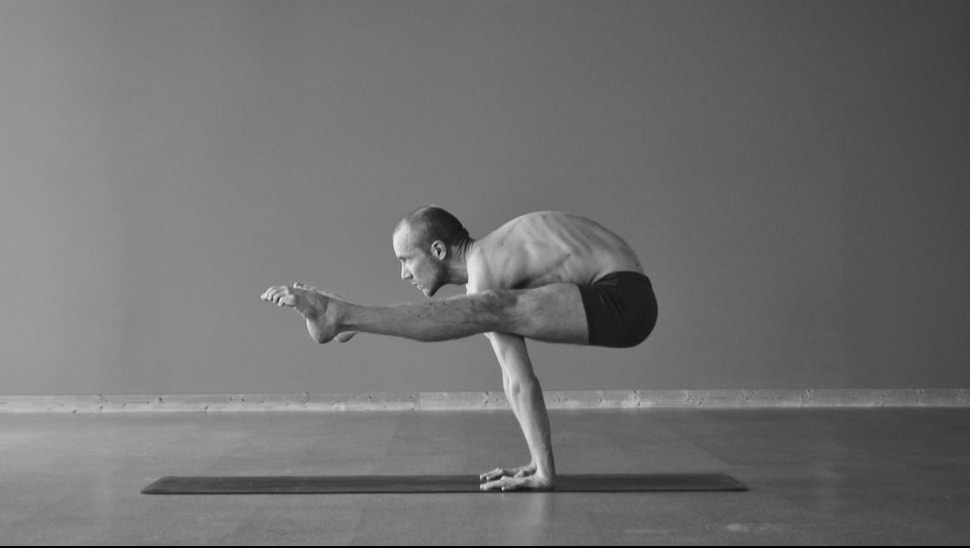

So why are our legs so sore after poses like Standing Bow, Standing Separate Arms Balancing Stick (pictured) or Standing Splits? These poses require eccentric contraction, meaning that a muscle lengthens as it contracts. The hamstrings of the standing leg eccentrically contract in these balancing postures, bearing the weight of the upper body as we tilt forward on the hip. The hamstrings must contract to keep the body from collapsing forward. It is a common misunderstanding that the standing leg hamstrings should relax in Standing Bow or the others. This couldn’t be farther from the truth; the hamstrings actually do most of the work. This complexity—asking the hamstrings to lengthen even as they hold the weight (eccentric contraction)—makes the muscles a lot more sore than concentric contraction. Most of the meditative, inward-looking spiritual traditions of the world agree that we overlook our true nature.

Our misunderstanding comes from the active (sometimes hyperactive) nature of the mind, which is constantly on the lookout for danger and opportunity. When these things are missing, the mind finds other activities: daydreaming, pondering, obsessing, discussing, watching TV, etc. There is an endless number of things we do to keep our minds busy. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that our busy minds give us things to do. Our identity problem comes when we mistake these mental activities for the true nature of the self. We don't realize that our emotions and mental activities are separate from us, and we identify ourselves with each emotion and thought: "I am angry," "I am happy," "I am hungry," "I am thinking." It can seem like splitting hairs, like an unnecessary distinction to make. But, are you your emotions? Are you your thoughts? Are you the breaths that you take or the beats of you heart? Are you the pain in your body? The more we explore these questions, we find that the "self" is not to be found in any of these elements. Nowhere is this concept stated more clearly than in the Yogasutras, "the Self appears to assume the form of thought's vacillations and the True Self is lost." (1:4) (1) The practices of yoga are many, but they all point to this issue. Every single practice of the body, breath and mind is designed to point us toward the true nature of the Self. 1. Stiles, Mukunda, Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 2002, p2-3. The last few days have been frustrating. I (this is Scott) wake up in the morning with no particular inspiration or focus. I don't feel motivated to get up and begin my day, much less my morning practice.

I know that I'm not the only one who has bad days, days when I don't want to do what I know I should. The funny thing is, I know from personal experience that these are the days when magic happens; the days when I feel uninspired but practice anyway. These days set the stage for the return of passion, when I will be newly focused and make progress. I don't know when those days will come, but I'm sure they will. Even though I know that inspiration will return, these days are drudgery. It takes all the strength I have to sit down for pranayama practice or do a few asanas. I try my best to practice, to do the work. What else can I do? Ida suggested changing things up a little, some advice she got from Swami Vishnudevananda. Change the practice or the time of day. I also cracked a new book, one of those with the short, 1-page messages. I read just one, probing for insight or inspiration. INTENTION

This posture continues the hip-opening of Tree Posture, increasing the focus on balance. Coming into balance on the toes requires significant strength in the foot and leg. Be sure to have the half-lotus foot high on the thigh before bending your standing leg. This way your half-lotus knee will be safer as you lower down. Once you are all the way down, try to get your standing thigh parallel to the ground. Make the spine upright. This takes some adjustment in the center of gravity, finding the right combination of up-on-the-toes, leg down, and body back. BREATH Take easy, relaxed breaths in this pose. BENEFITS This posture builds great focus. It creates strength in the legs, feet and toes and openness in the hips. NOTE Come in and out slowly, avoiding any quick movements. If you feel tightness or pinching in the half-lotus knee when you bend forward or when bend your standing leg, don’t go further. Work on your Tree Pose. Sit your opposite hip onto your heel (ex. left hip on right heel). If you try to hover with the strength of your standing leg you can easily strain the tendons in the front of the knee. Excerpt from the Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual - Intermediate We become teachers for many different reasons: to improve our understanding, a sense of duty, the need for income, to be a leader, to have power...

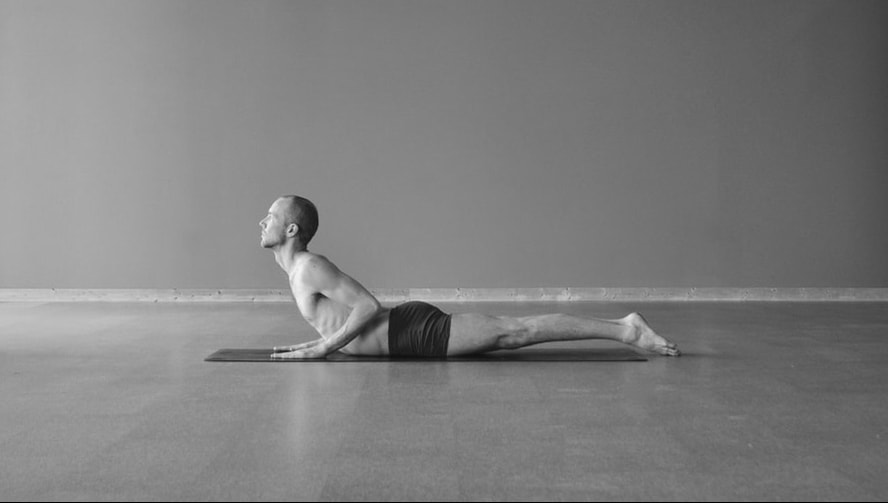

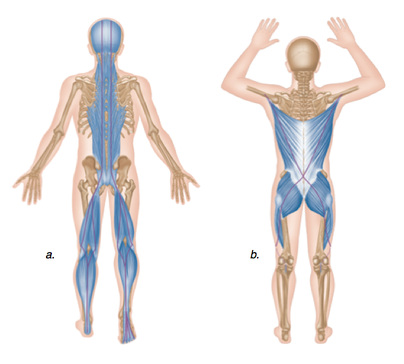

Once you are teaching, the story can change quickly. You have to work around schedules, maintain time for your own practice and deal with frustrating students. It is easy for the grand vision of teaching to turn into a slog that is fraught with resentment. It doesn't take much to resent your students. They don't work as hard as you ask them to, they don't take your advice. How many times have you told them to keep their hip down?! Why don't they do it?! Sometimes it seems like it's not even worth the effort you put in. At times like this, when you feel frustrated by your students, try to approach them and their practice with kindness and patience, not resentment, impatience or anger. Especially when you correct them or adjust their posture. It is tough, because anytime we correct a student, it comes from dissatisfaction with their performance. They are doing something wrong enough that we notice and feel compelled to intervene. This means that every "correction" we give a student begins with our own irritation and has the potential to bloom into frustration or even anger. Is it possible to turn our dissatisfaction with a student's performance into something more generous? How can we serve them and make them understand better? (Because let's face it, nearly every mistake comes from misunderstanding.) Above all, we (the teachers) are here to serve the students. They are not here to serve us. Sure, it is important to honor the purpose of the practice and be sure to do things right, but this is actually in service of the student, not the teacher. When you teach, and when you correct your students, do it out of service, generosity and kindness. Don't do it to get something from them. Do it to give something to them. Don't do it out of frustration or anger. Do it out of love, to help. A teacher's patience is infinite, because the goal is to teach the student. And the goal hasn't been achieved until the student understands. Stretching Posture (Paschimottanasana, pictured above left) and Forehead to Knee Posture (Janushirasana, pictured above right) are often grouped together and thought of as similar postures. It seems like one is just the two-legged version of the other. But they work differently in the body, targeting completely different layers of the tissue system. Stretching Posture lengthens the back of the body in a straight line, more or less. Up the back of the legs via the hamstrings and up the back via the erectors of the spine. This is pictured above in figure "a."

The defining characteristic of Forehead to Knee Posture is the bent leg. The hip rotates and opens (abducts) while the knee bends. That is how we get the foot near the groin. This action completely changes the tissue relationships on the back of the hip and pelvis. It lengthens the gluteus maximus (butt muscle) and tightens the IT (ilio-tibial) tract, a super tough band of tissue that runs down the outside of the leg and across the knee. See figure "b" above. Next time you do Forehead to Knee Posture, pay attention to your bent hip, knee and the outside of the leg. Notice the relationship between the leg and the spine. It is more complex than Stretching Posture. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed