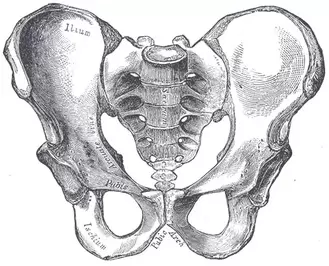

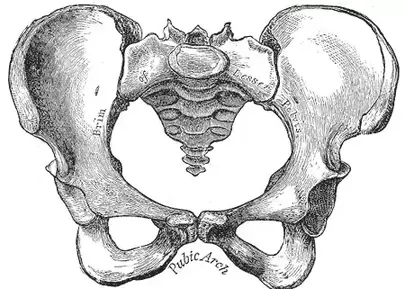

Source: pediaa.com Source: pediaa.com This blog discusses engagement of the pelvic floor, or what is called mula bandha, the root lock, in yoga. To get where we are now, it's useful to start with a little history. Prior to the 1700s, it was thought that the body was an alchemical vessel. Through manipulating the body, we could move the winds (vayu) or direct life energy upward (sometimes called kundalini). These were practices of hathayoga. It was also believed that life force could leak out of the openings in the body. Therefore one would apply locks and seals (bandha & mudra) to various parts of the body to prevent energy from escaping. One of these, mula bandha, involved the pelvic floor muscles. Nowadays, these beliefs have been extrapolated to mean various things. Sometimes it's taught that pelvic floor engagement makes the body more "stable". Yoga International says that mula bandha is "stabilizing and calming" and "enhances the energy of concentration". But in asana practice, this will not stabilize the body. Here's why. The pelvic floor muscles to do not move the skeleton. Therefore, they cannot make the skeleton more stable. They attach to the opening in the bottom of the pelvis, between the tailbone and the pubic bone. When the pelvic floor muscles engage, they lift the organs above them and tighten the openings of the pelvis. (This is very different than muscles that cross a joint and move the skeleton.) In short, they do not stabilize the skeleton in an asana, because they do not move the skeleton. There is also concern about over strengthening the pelvic floor. This can lead to constipation and pain. Just like any muscle, too loose is not good but too tight is not good either. In conclusion, it is good to consider whether engaging the pelvic floor is useful. If we are trying to manipulate the flow of subtle energy, it may be. If we are trying to stabilize the skeleton, it is not. Sources: Yoga International, Better Health

0 Comments

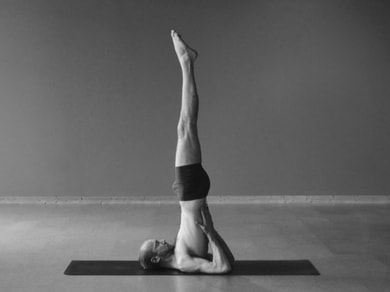

In this blog, we'd like to discuss three posture that are worth reconsidering and perhaps even removing from a posture practice. Will this be controversial? Perhaps. That's because there are many valid reasons to practice postures, some of which lie in tradition. Asanas have long been part of a practice to transcend the physical body. One would put themselves in strenuous positions to burn karma. Or one would sit in an asana and meditate. Therefore it was of little concern whether one would injure the body or not. We are not suggesting there is a right way to approach postures. However nowadays, many come to yoga to be healthy. Regardless of how we think about the practice as a whole, we should take into consideration what is happening in the body. After all, these are physical practices. The first posture worth reconsidering is Standing Splits. Here's why: In this posture, the pelvis tilts very far forward to allow for the upper body to come close to the standing leg. This lengthens the back of the standing leg hamstrings. However, because of the relationship to gravity, the standing leg hamstring is also the muscle exerting force. (This is eccentric contraction: the muscle gets longer while exerting force.) This is potentially a compromised position for the hamstrings. The hamstrings are long and contracting. Then, when the lifting leg attempts to reach higher, the hamstrings are pulled even longer. This makes the hamstrings very susceptible to injury in this position. What can we do instead: Balancing Stick is a great alternative. It builds balance and strength in the hamstrings but doesn't require an extreme range of motion.  Heron Heron The second posture worth reconsidering is Heron. There is next to no therapeutic function for this posture. It is essentially a hamstring stretch on one side and a deep knee flexion on the other. This puts both the knee and the hamstring in a compromised position. In order to sit upright enough to lift the leg, the pressure has to increase through the bent knee. Therefore, the deeper you get into the posture, the more pressure is going through the knee. Just to sit in this position is already hyper flexion of the knee. Increasing the pressure while in this position is questionably safe. What can we do instead: Paschimottanasana will stretch the hamstrings. Chair pose will flex the knees while stabilizing them and building strength in the quadriceps, and Firm will flex the knees without also requiring hamstring length.  Shoulderstand Shoulderstand Last but not least, it's worth reconsidering Shoulderstand. This is probably the most controversial. That's because Shoulderstand is an older posture in yoga, predating the twentieth century. Iyengar, Sivananda and others famously included this posture as one of the gems of asana practice. However this posture developed with the belief that life force exists in your head and drips into the abdomen. Therefore, one should turn the body upside down to preserve that life energy. Regardless of how we feel about that belief, it is important to note the extreme flexion of the neck this position requires. In addition, the weight of the body is coming down through the neck. Those things together make this very hard on the neck. If we practice it, we should take great care to be safe. What can we do instead: If we want to go upside down, we can practice Headstand or Tiger. These are admittedly more difficult in some ways, but they do not put pressure on the neck while it's flexed. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed