|

Over the past several months, we've written 12 entries about hathayoga, a form of yoga with a specific history and set of methods. The term "hatha" has been appropriated by modern western yoga to mean "the physical practices of yoga, especially asana," but that was not its meaning for most of history. For serious and dedicated practitioners of yoga, it is worth understanding the history of this tradition.

Below are the 12 blog entries about hathayoga. What Is Hatha Yoga? The Meaning(s) of Hatha The Birth of Shavasana Preserving the Essence of Life The Two Padmasanas The Strange Story of the Hatha (Yoga) Pradipika Yoga Is Destroyed By These 6 Causes Yoga Succeeds By These 6 Causes Mudras The 15 Postures of the Hatha Pradipika, Part 1 The 15 Postures of the Hatha Pradipika, Part 2 The 15 Postures of the Hatha Pradipika, Part 3

1 Comment

Tradition

There is some lively discussion, even here at Ghosh Yoga, about the meaning and value of tradition. What is tradition? The easy part to understand is that it is a practice or belief that comes from the past and has been passed down for generations. The sticky part is this: how static is the practice or belief? Is a tradition defined by its unchanging nature through time? Or does each generation adjust the practice to fit the time and culture? Does its continued evolution and relevance define a tradition? Ancient Obviously, it is silly to assume that something has more value simply because it is old. There are two underlying implications when we refer to something as "ancient" and mean it as a good thing. The first is the belief that humans in previous times were more connected, more insightful, more intuitive, etc. than we are today; that today we are disconnected and insipid. Is that true? The other implication of an "ancient" claim is that of tradition; that is, a practice that has been passed down for generations. If it is an old practice, it must have been found to be valuable by generations of people. And if generations of people found it useful, it must be useful for me too. Lineage A lineage is simply the traceable line of descent from one person in history to another. In the context of yoga, the lineage is not usually a bloodline but one of teacher and student. The assumption that usually accompanies any discussion of lineage is that the teachings are the same, which is more a question of "tradition" than of "lineage." But tradition is not inherent in any lineage, whether it is family related or teacher-student. The practices of one generation could theoretically be drastically different from the last, and the lineage would be just as intact. For the most part, when we talk about lineage, we are really talking about tradition and practices that have been passed down. The real questions to ask ourselves are not "what is the tradition?" "how old is this?" or "who was your teacher?" They are "what am I seeking?" and "what are the presumed results of this practice?" INTENTION

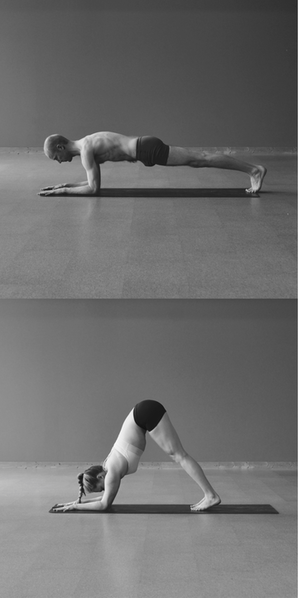

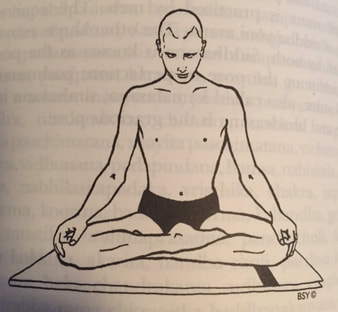

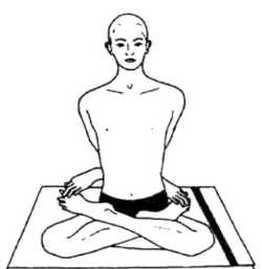

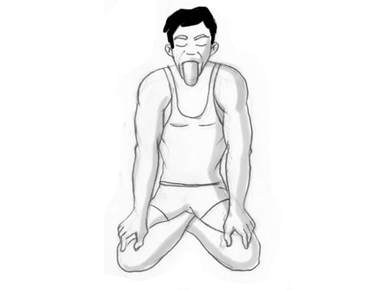

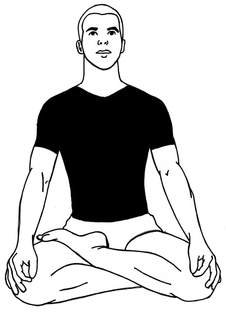

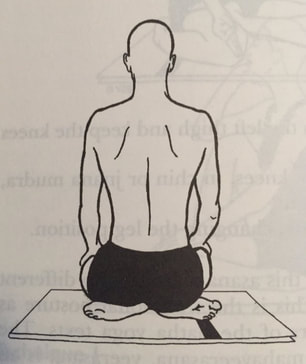

Preparation 1 (pictured top) is commonly known as the Forearm Plank. This position begins to build strength in the chest, shoulders and arms with the body in a very supported position. Only about half of the body’s weight is in the arms, and we use the large pectoralis muscles of the chest. At this stage, it is of vital importance to setup your hand, arm and shoulder position well. This is the foundation that we will build upon. Preparation 2 (pictured bottom) shifts the weight of the body forward and up, gradually moving us toward Tiger. The position of the shoulders is different from Preparation 1. Now the body is upward and the shoulders are flexed more. The muscles that get used will shift. Keep the arms, elbows and shoulders stable and engaged. It is important in both of these exercises to move the shoulder blades away from the spine. The chest muscles engage to move the shoulders forward (toward the chest). As the shoulders flex, like in Preparation 2, the shoulder blades rotate and come onto the side of the ribcage like wings. BREATH In Preparation 1, the breath will be small. The muscles are tight, so breathing is nearly impossible. Stay calm, keep the body tight, and take small breaths. Don’t relax the body (especially the belly) to enable large breaths. In Preparation 2, the body is not quite as engaged. The breath will still be short, but less than in Preparation 1. Excerpt from the Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual - Advanced. The last four postures instructed are "the essential four." (We also wrote blogs about the first 5 and the second group of 6.) "Siddha, Padma, Simha, and Bhadra---these four are the best." 12. Siddhasana "Press the perineum with the heel of the foot. Place the other foot above the penis. Hold the chin steady on the heart. Remain motionless. Restrain the senses. Look with a steady gaze between the eyebrows." This is another highly-regarded traditional meditation posture that has fallen out of popularity in modern yoga. Many old texts refer to Siddhasana as the single most important yoga posture. 13. Padmasana A "Place the right foot above the left thigh and the left foot above the right thigh. Hold the big toes firmly with both hands from behind. Put the chin on the heart. Look at the tip of the nose." This position, with the arms wound behind the back, has come to be known as Baddha Padmasana, or Bound Lotus, in the modern era. Padmasana B "Drag the upturned feet onto the thighs. Place the upturned hands in the middle of the thighs. Keep the eyes on the tip of the nose. Hold the root of the front teeth with the tongue. Place the chin on the chest...Some call this Padmasana." The text describes this second posture directly after the first Padmasana. It involves a different hand position and the tongue touching the teeth. Probably this variation was a posture that came from a different school or tradition than the first. 14. Simhasana "Place the ankles below the scrotum on both sides of the perineum---the left ankle on the right, the right ankle on the left. Place the hands on the knees. Spread the fingers. Open the mouth. Gaze steadily at the tip of the nose with a well-concentrated mind." The instructions of this posture are quite clear. It is rarely practiced in modern yoga, and when it is the legs are often uncrossed. 15. Bhadrasana

"Place the ankles below the scrotum on both sides of the perineum---the left ankle on the left, the right ankle on the right. Grasp the feet, which are on their sides, firmly with the hands. Remain motionless." INTENTION

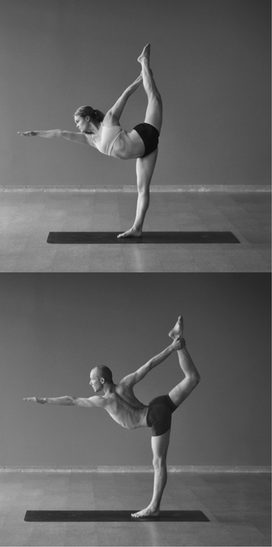

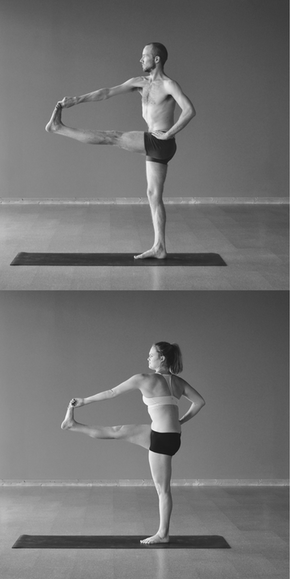

This posture is terrifically complex. It bends the spine backward and twists it, opening the chest and shoulders. The kicking leg moves toward the splits, all while balancing on one leg. Do your best to keep the kicking hip down. Even hips create a truer backbend in the spine and balanced engagement of the standing hip and leg. Keep the head and chest up while the belly button drops and faces the ground. BREATH Lungs are extended in this posture, breath should be about 70%. Use the breath to stretch the chest up and forward. Keep the breath relaxed, even as the back muscles engage and the heart rate rises. BENEFITS This posture builds balance, focus and determination. The backbend massages the adrenal glands, reducing stress. It stretches the chest, legs, hips and shoulders while building strength in the feet, legs, hips, back and shoulders. This posture truly challenges and benefits the whole body. NOTE Take great care not to hyperextend the standing knee in Standing Bow. Make sure that the standing knee is stacked directly over the ankle, not pushed behind it. Hyperextending the knee damages the ligaments of the knee and will eventually create issues in the hips, ankles and feet. Excerpt from the Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual - Intermediate. Most of us were trained to make money, get possessions, gather belongings and generally acquire stuff. Maybe I'm the only one, but I grew up thinking that a better job, more money, a bigger house and a family to love meant success in this life. And so we work hard to draw resources and people toward ourselves, like we are trying to annex them to ourselves, making us bigger, stronger and more substantial.

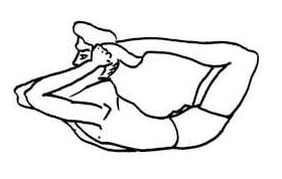

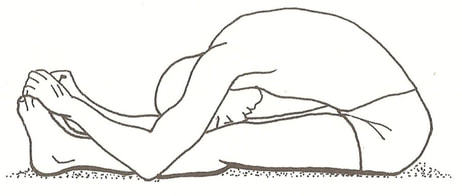

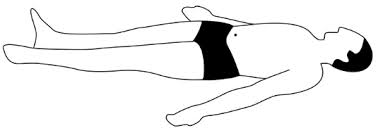

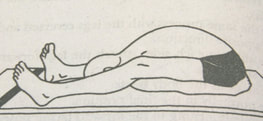

But of course these things and people are not ourselves, and when we confuse the two we can become conflicted about our own identity and purpose. I find myself asking: if this effort to draw things toward the self generally ends in conflict, what is the opposite? PUSHING AWAY The obvious answer is pushing things away, which can bring our sense of self into sharp relief. As we separate ourselves from all other things, we can see clearly what delineates me from not me. An issue, though, with this approach is the way that it isolates us from other people and the world. We do not exist in this world alone. We must interact with food, nature and other people to survive. Is it possible to balance the two approaches, or find a middle path? THE MIDDLE PATH Any middle path is difficult to traverse since it requires constant awareness, balance and adjustment. We tend toward extremes in almost everything we do and think, so we will alternate between periods of "drawing toward" and "pushing away." Finding middle ground may mean adjusting in a new direction at any given time. This requires diligent awareness of our mental state. The first 5 postures in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika include mostly seated postures, many of which have been changed or forgotten over the centuries. The next 6 postures are mostly still done the same way today as described in the text. 6. Uttanakurmasana "Assume Kukkutasana, join the neck with the hands, and lie on the back like a turtle." The name means "Tortoise lying on the back," which is exactly what this posture looks like. Another meaning of "uttana" is "upright," so some do a posture with this name that is seated upright. 7. Dhanurasana "Bring the toes as far as the ears with both hands as if drawing a bow." This posture is quite difficult to do in its full form as described. Modern yogis have kept the posture but made it more accessible by simplifying it. You've probably done Dhanurasana by simply grabbing the feet and kicking up and back. 8. Matsyendrasana "Place the right foot at the root of the left thigh, and the left foot outside the right knee. Grasp the feet and twist the body." This posture is still practiced the same way, commonly referred to in English as the "spinal twist." Interestingly, it is instructed here not as the ultra-advanced (and newer) Purna Matsyendrasana, with the bottom leg in Lotus. It is instructed as what has come to be known as Ardha Matsyendrasana, or Half Matsyendra Posture. 9. Paschimottanasana "Stretch both legs on the ground like sticks. Grasp the toes with both hands. Rest the forehead on the knees." This posture is given the honor of "the best among asanas." It is practiced pretty much the same way today, with the exception that some schools teach it with a flat spine, reaching the head toward the feet. 10. Mayurasana "Hold the earth with both hands. Place the sides of the navel on the elbows. Rise high above the ground like a stick." This posture too is practiced in the same way today. It is very difficult, so it is not common in a regular yoga class. But the posture is the same. 11. Shavasana

"Lying on the back on the ground like a corpse is Shavasana." This posture has become a staple of modern yoga classes. Nearly every class now ends with Shavasana. INTENTION

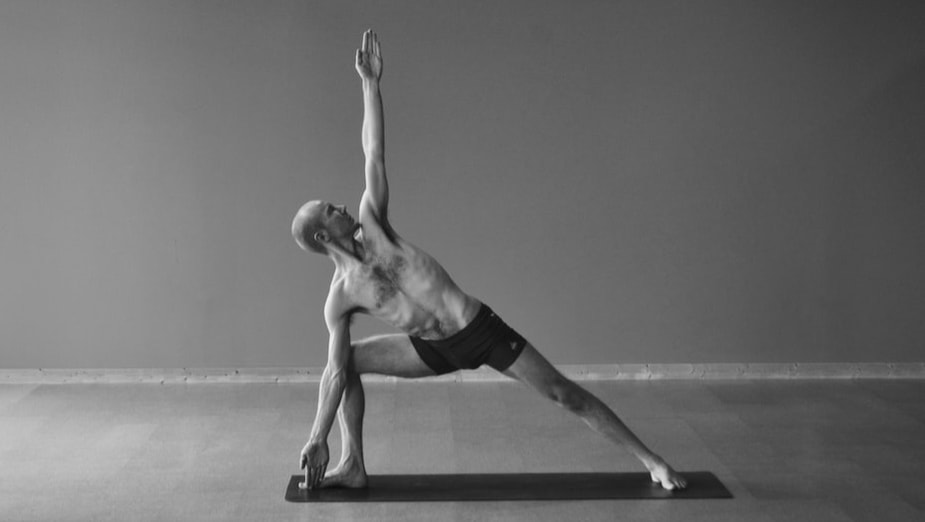

The main elements of this posture—the standing leg and hip—can be overshadowed by the challenge of balance and the effort to straighten the kicking leg. First and foremost, this posture is about the uprightness of the standing leg and spine. If you must keep the kicking leg bent in order to maintain an upright spine, that is perfectly acceptable. Push the big toe of the standing foot down and keep the standing foot as still as possible, though it may be wobbly when starting out. BREATH Breathe deeply and relaxedly in this posture. You may notice that your breath shortens as you focus on staying upright or stretching the leg forward, but breathe deeply, expanding the chest. BENEFITS This posture builds strength and stability in the legs, hips and back. It creates flexibility in the hamstrings and improves balance and focus. It twists the spine slightly, improving circulation to the vertebral discs. Excerpt from the Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual - Beginning. As we have dug into the texts and practices of hathayoga, one piece of advice stuck out to us from the Hatha Yoga Pradipika: "Needless austerities" hinder us on our yogic path. We got to thinking about what "needless austerities" we might be performing nowadays, and realized that "alignment" has the danger of being one.

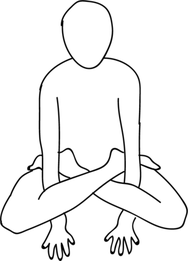

The lesson about "needless austerities" is about losing the forest for the trees. When we get invested in certain practices, we can become attached to the practices themselves and lose sight of the larger goal, even to the point that we continue the practices when they hinder our larger progress. When any practice becomes an end in itself, we need to assess it honestly to make sure it is serving us. It is easy to obsess about alignment, making the entirety of the physical practice focused on it alone, as if the greatest goal is to make the body and the postures aligned. Which brings us, as always, to the question: what is the larger goal of physical yoga practice? How does alignment serve us on our path toward that goal? Without a doubt, there will be many answers to that question, even some that contradict each other. To us, the physical practices of yoga bring health to the body, undo improper movement and habit, leading to physical, energetic and mental balance. More advanced physical practices facilitate concentration and stimulate the nervous system. So how does alignment serve these goals? (Or, if you have different goals, how does alignment serve them?) For most of us, and for most of our students, alignment is vital for the first few goals: bringing health and removing improper movement habits. By using the body properly, we can reawaken muscles that have gone to sleep, undo imbalances that have developed over decades and ideally create better movement patterns. This echoes up the chain into the nervous system, balancing the mind and developing the well-loved "mind-body connection." The word "alignment" can be misleading, not least because it means bringing things into lines, which is not at all how the body is put together. Accomplishing these goals in the body doesn't necessarily mean making straighter lines or more perfect angles. It means using the body in a balanced way and, ideally, identifying the imbalances of your students and adjusting accordingly. After describing the 6 obstacles and 6 necessary qualities for success, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (~1500 CE) goes on to describe 15 postures, the largest number to that point in history. The first 5 postures are below. Many of these old (traditional?) postures have gone out of style and practice in the last hundred or so years. Others are still with us. 1. Swastikasana "Place both soles of the feet inside the thighs and knees. Sit up straight." This is a great posture for breathing and meditation practice, stable but less challenging than the full Lotus. Sadly, as modern western yoga practice has become less seated, the posture has fallen out of popularity. 2. Gomukhasana "Put the right ankle on its left side beside the buttock. Likewise, put the left ankle on its right side." (a) "Place the right ankle next to the left buttock and the left (ankle) next to the right (buttock)." (b) The two instructions above are from different translations of the same verse. The slightly different translations of right and left lead to completely different instructions for the posture. By far the more common usage is the second translation, which is pictured above, with the knees crossed on top of each other. It is unclear, though, which translation is actually accurate or correct. 3. Virasana "Place one foot on top of one thigh, and the other thigh on top of the other foot." In modern yoga practice, this posture has taken on many forms which correspond to this description in varying degrees. The best we can tell, this is describing a Half-Lotus sort of position. 4. Kurmasana "Cover the anus with the crossed ankles." The instruction in the text is quite clear, as pictured above. This posture has fallen completely out of practice as far as we know. The name Kurmasana has been adopted to describe another position for the past 100 or so years, a deep forward bend with the shoulders underneath the knees, pictured below. 5. Kukkutasana

"Settle in Padmasana. Put the hands between the knees and thighs. Place the hands on the earth. Lift into the sky." Of these first 5 postures in this important text, only Kukkutasana is both crystal clear in its instruction and still practiced the same way today. Continue reading about the second group of 6 postures, and the third group of 4 postures. a) Translation by Brian Dana Akers. Published by yogavidya b) Unknown translator. Commentary by Swami Muktibodananda. Published by Yoga Publications Trust. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed