|

Modern yoga practitioners often embrace the idea of equality and relate it to the ancient spiritual teachings of yoga. This can lead to positive developments like the cultivation of compassion and humility. But it can also lead to more troublesome developments like the belief that any suffering is in our own minds and therefore our own fault, which can cause us to be apathetic, overlooking ingrained prejudice and inequality.

Let's take a look at where the concept of 'equality' in yoga comes from, and what it means when someone says 'we are all one'. THE ESSENCE... In many ancient yogic texts, there is the belief that all of reality is underpinned by a single universal consciousness, called brahman. This means that a computer is nothing but brahman, a dog is nothing but brahman, you are nothing but brahman, and I am nothing but brahman. It is not unlike the recognition that all the objects in the universe are made of energy, whether that energy manifests as light, a hydrogen atom, a drop of water or a human being. When you look underneath the differences in external appearance, the same essence underlies everything. So when a yogi says 'we are all one', this really means that the essence which underlies all existence, including yours and mine, is the same. NAMES AND FORMS...AND HUMAN IMBALANCE But what this does not mean is that you and I are the same, nor that our experiences are the same. In the very same ancient texts is the recognition that when we are born as humans, we take on a distinct physical form that is separate from other forms. For example, I am separate from the computer, and I am separate from you. We take on a name and a form. Our essence is still brahman, but our names and forms are different. The goal of spiritual practice in this vein is to recognize our true essence as brahman rather than this body and mind. But it does not mean that our bodies, minds, histories, goals and identities are the same. The physical world is quite different from the spiritual world. We must recognize that we, as humans, create imbalance in the world. We take objects from one place and move them to another. We cut down trees to build houses, and we protect our own families by destroying others. While these things are all, by definition, brahman, that does not mean that our 'names and forms' are all inseparable. If it did, we would be just as happy to be eaten by a fish as to eat the fish ourselves. SPIRITUAL EQUALITY vs PHYSICAL EQUALITY While we may believe that we are the same on an essential, spiritual level, this certainly does not manifest into the physical realm of human bodies and minds. The way that the yogic concept of spiritual equality — that 'we are all one' — manifests in the world is infinitely complex and frustrating. Our human minds and bodies are designed to be selfish, even if our spirits are 'one'. We are born with the need to feed and protect our bodies at the expense of pretty much everything around us. This is what the yogis call 'ignorance' (avidya) and 'ego' (asmita), two foundational problems of every human. So next time someone says 'we are all one', recognize that it is a spiritual statement but not a physical, human one. If we seek to make the physical world more like the spiritual one, we must make the effort to subordinate our own desires to the good of others, and to make the human world more equal through our own action.

0 Comments

Two weeks ago, the state of Alabama overturned a 30 year ban on yoga instruction in public schools. Now yoga can be taught in schools there, with a few caveats.

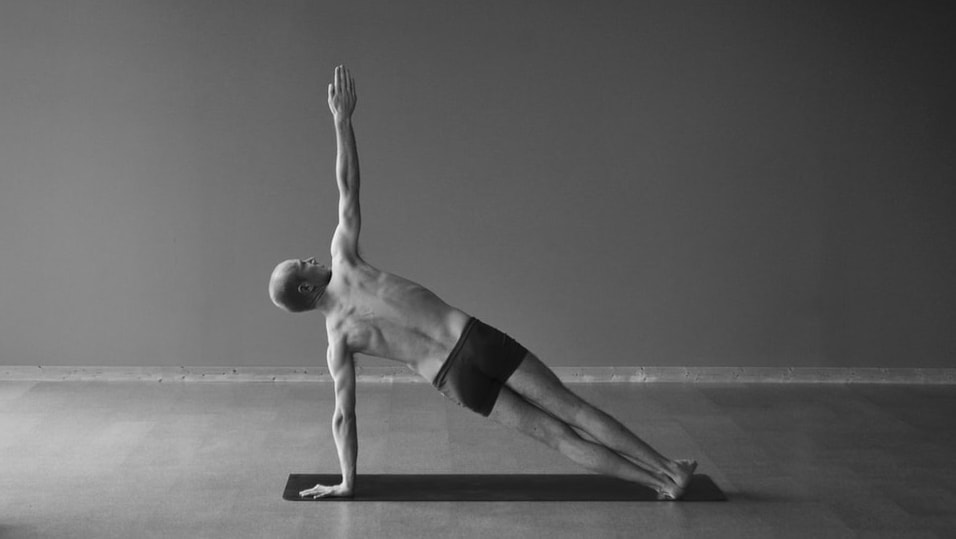

The bill continues the transformation of modern yoga into a secular, physical, health-centric exercise practice, a process that began about 100 years ago in India. As far as the bill promotes health in students, it is to be applauded. But its understanding of the essence of modern yoga is off the mark, which leads to a couple mistaken restrictions, like the exclusive use of the English language. According to the bill, "All instruction in yoga shall be limited exclusively to poses, exercises, and stretching techniques. All poses shall be limited exclusively to sitting, standing, reclining, twisting, and balancing. All poses, exercises, and stretching techniques shall have exclusively English descriptive names. Chanting, mantras, mudras, use of mandalas, induction of hypnotic states, guided imagery, and namaste greetings shall be expressly prohibited." These stipulations come from concerns over the possibility of yoga's inherent religiosity or spirituality. Religious teaching of any kind is not permitted in public schools, and some worry that even non-religious yoga practices are a trojan horse, smuggling Hinduism or Buddhism into the curriculum. At the root of the confusion is a common term: yoga. It can refer to old practices or new, spiritual, religious or physical. The confusion arises when we do not know which are being taught, or when we think they are all the same. The Alabama bill makes this mistake, equating yoga practice with Hinduism. It requires parental permission for any student to participate, including the statement, "I understand that yoga is part of the Hinduism religion.” Let’s look at this misunderstanding in a little more detail. Practices called yoga have been around for thousands of years. For most of history, yoga was spiritual, a practice of linking one's awareness with the eternal soul within, or with a deity. In this way, yoga can be associated with Hinduism. But yoga that is practiced today is different. In the early 20th century, yoga practice became largely physical and focused on health, downplaying or entirely dropping its spiritual and religious elements. According to yoga scholar Mark Singleton, conceptions of yoga in the 20th century are shaped by "modern physical culture, 'healthism', and Western esotericism." In other words, modern yoga is closer to gymnastics than prayer. Even though they share the same name — yoga — modern practice is fundamentally different from earlier spiritual forms. Confusion is common. Most people who do not practice yoga, and even many who do, mistakenly think that the postures and exercises in a yoga class are ancient and inherently spiritual in nature. But most of the stretches and asanas in a yoga class come from calisthenics, gymnastics and dance as recently as the last few decades. As such, they are exercises that look good, feel good and improve our health. Singleton writes, "among outsiders and practitioners alike, there is often little awareness that these modes of [modern] practice have no precedent (prior to the early twentieth century, that is) in Indian yoga traditions.” So it is no surprise that parents and politicians fear inherent Hinduism in yoga, even though little or none exists in its modern iterations. THE SANSKRIT LANGUAGE This same misunderstanding appears in the Alabama bill with regard to language. Though it is not stated explicitly, the insistence on "exclusively English descriptive names" seems to be a way to prevent the use of the Sanskrit language, most likely due to fear that Sanskrit will smuggle in Hinduism or Buddhism. But non-English languages are fundamental parts of many disciplines. In music, every student learns the Italian allegro, andante, forte and piano, words meaning fast, slow, loud and soft. And biologists often use Latin to classify species like homo sapiens. Some yoga postures are named after Hindu deities. For example, Hanumanasana is named after the god Hanuman; Virabhadrasana is named after Virabhadra; Vasishthasana is named for Vasishtha. These names and their deities are rightfully forbidden from public schools, just as any mention of Moses, Jesus or Mohammed would be. But other postures are named for secular objects like shapes and animals. There is Trikonasana, the Triangle Posture; Vrikshasana, the Tree Posture; Bhujangasana, the Cobra Posture, among countless others. Surely these names do not infringe upon religious freedom or inherently imply Hindu worship, whether in English or Sanskrit. And there is no harm in learning the Sanskrit word for tree. At its core, then, the new bill in Alabama continues the secularization, exercise and health focus of modern yoga. In this way, it isn't terribly different from the twentieth-century innovations of Vivekananda or Yogendra, who removed unattractive traditional beliefs in favor of modern ones. — Singleton, Mark. 2010. Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford University Press. The issue of cultural appropriation has been troubling yoga lately. Did the West steal yoga from India? Does India own yoga? Do Indians naturally and inherently understand yoga because of their cultural heritage? Is it in their blood? Some have suggested that non-Indians should not teach yoga.

Three elements are worth stating briefly before we answer the central question. First, any claim that intelligence, knowledge, understanding or ability can be judged by a person’s heritage or race should be recognized for what it is. At best it is nationalism, at worst it is racism. With yoga, the sentiment is understandable on several levels. Yoga has become a billion dollar industry beyond India's borders. Furthermore, much about what modern yoga is today shifted drastically while India was under British rule. The desire to reclaim a popular system as one’s own is relatable. Yoga, like many other trades, practices or professions can be passed down generation to generation. At a young age, the next in line takes over the family business. They grow up around it and learn everything there is to know about it from the older generation. This is different. This is closer to a master/apprentice or guru/disciple relationship. In this case, the second generation will have knowledge and understanding that the outside world won't have. But this is because of the immense time spent learning and studying the craft. If the child of an expert chooses not to study or practice yoga for example, they cannot expect to know a great deal about it even if they are directly related to an expert. Second, heritage of a subject or art form in a country does not give that country exclusive ownership of it. Ideas and goods have been traded internationally for thousands of years, evolving as they go. The Chinese cannot claim the exclusive right to make paper, the Babylonians mathematics, nor the Indians yoga. Third, we need to be clear about what we mean by 'yoga'. This may seem obvious, but it is nuanced enough to deserve a little explanation. There is no doubt that yoga originates in India. The ancient Katha Upanishad is its first known explanation. For thousands of years, yoga was a spiritual practice of uniting one’s awareness with an eternal spirit within, or with a deity. In the twelfth century, a practice with bodily elements developed, called hathayoga, the 'yoga of force'. But the goal was the same, to create spiritual unity with a higher being. In the early twentieth century, this changed drastically. Over the course of a couple decades, yoga was refashioned as a modern, scientific, physical practice for health. Modern yoga represents a fundamental break from the older spiritual iterations. It shows influence from European physical cultures like gymnastics and calisthenics. As such, even India’s claim as the singular authentic source of modern physical yoga is worthy of healthy debate. But let’s get back to the central question: who should be teaching yoga? The answer is the same as for any topic, whether mathematics, physics, astronomy, music or literature. A topic should be taught by those who have knowledge of it. Regardless of their age, gender or race, a teacher needs no more — and no less — than expertise of their subject. This gets more complicated because of the unequal power structures permeating the world. Those that know should teach. However, those that have resources should work to make sure that those who have less still have the opportunity to learn if they choose to. Perhaps the question is not who should teach, but rather how do we make high quality education affordable and available. This issue has quickly moved in the wrong direction as more and more "teacher" trainings see big money to be made. This is in exchange for the promise of the title of teacher, often with not enough regard for the task of actually training a teacher. As for the suggestion that non-Indians should not teach yoga, the nationalistic element should quickly be discarded. Furthermore, we need to address the quality of yoga teachers. The only worthwhile question to ask about a potential yoga teacher is this: do they know what they are doing? |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed