|

The "Hatha Yoga Pradipika" (15th century CE) is arguably the most respected and referenced textual source of hathayoga. Oddly, its true name is Hathapradipika. Only later when referred to by other texts was the word "yoga" added to its title.

The Hathapradipika is mostly a compilation, drawing verses from at least 20 other texts that preceded it. Notably, it is "the first text that explicitly sets out to teach Hatha Yoga above other methods of yoga." (1) Like so many other compilations, it contains teachings from a wide (and sometimes contradictory) swath of history and traditions. With its instruction of 15 postures (asanas), it is the first yoga text to include asana among its techniques. "Prior to everything," it says, "asana is spoken of as the first part of hatha yoga. Having done asana one gets steadiness (firmness) of the body and mind; diseaselessness and lightness (flexibility) of the limbs." (2) It is worth noting that not a single one of the postures is done standing. It marks a turning point in yoga history because so many of the texts that come after it quote it directly. It is considered by many to be encyclopedic and authoritative. In addition to postures (asana), the Hathapradipika teaches 6 cleansing acts, 8 breathing practices, 10 mudras and a whole chapter on samadhi. These non-postural practices have largely been lost in western yoga, even that which is called "hatha." 1. Mallinson, James. Hatha Yoga entry in Vol. 3 of the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism 2. Hathapradipika. Chapter 1, Verse 17.

0 Comments

Putting the leg(s) behind the head rounds the spine forward, a powerful counter to Full Backbending. These postures are a full-body nervous system "stretch." To access the nervous system in this group of postures, there are three elements of vital importance: 1) lengthening the spinal chord by rounding the spine, 2) compressing the nerve plexuses in the chest and abdomen, which is also achieved by rounding the spine forward, and 3) tensioning (stretching) the sciatic nerve by rotating and flexing the hip.

The spine should be "hunched" forward in these postures. Much of their benefit is in the lengthening of the nervous system on the backside of the body, including the spinal chord and sciatic nerve. The head and neck need to be upright enough to hold the foot in place behind the head, but the spine should be rounded as much as possible. Compressing the chest and abdomen calms the nervous centers there. These are the same plexuses that we stretch and stimulate in deep backbends. Here we compress them, countering the backbends. This is similar to the complimentary positions of Camel and Rabbit postures, which is why Leg Behind the Head postures should be practiced after Full Backbends. Leg Behind the Head balances and quiets the nervous system in preparation for the inner practices of Sensory Control and Meditation. Excerpt from Advanced 1 Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual We went through the texts of Bishnu Ghosh (Yoga Cure, 1961), Buddha Bose (84 Yoga Asanas, 1938), Gouri Shankar Mukerji (Yoga & Our Medicine, 1963), Monotosh Roy (Cream of Yoga, 1970s) and Dr. PS Das (Yoga Panacea, 2004) to make a comparative list of the postures in the Ghosh Yoga canon.

What we found were 113 postures, 27 of which were shared by the 3 texts published during Ghosh's lifetime (Ghosh, Bose & Mukerji). You may be surprised by which 27 they are. We listed and organized the postures here. Two things surprised us most: The late appearance of Ushtrasana, the Camel Posture. It has become a staple of many yoga traditions including Ghosh. It is described by all the texts except Buddha Bose's, leading us to believe that it didn't enter the lexicon until later. (Read our more recent post about The Lost Camel Posture.) The complete absence of Dandayamana Dhanurasana, the Standing Bow Pulling Posture, which has become central to Bikram Choudhury's yoga system. None of the 5 texts describe this posture. (Read our more recent post about the Origins of Standing Bow.) “How do I start a home practice?”

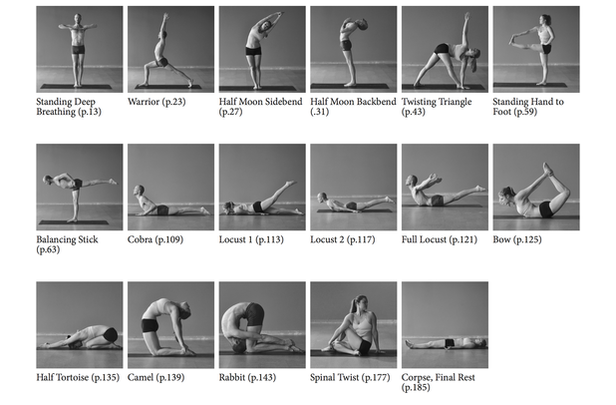

We get this question a lot. For anyone interested in a home or self practice, anyone without access to a studio, or anyone on the road, this is an important question to explore. START SMALL Starting a home practice can be overwhelming. It’s challenging to decide what to practice and for how long. With so many postures and practices, it can feel like we can’t possibly practice everything that we should practice. An important thing to remember is that some practice is always better than none. If this is new to you, we recommend keeping it short. You will find that 5 minutes is much easier to carve out than 2 hours. Once, you build up the habit, you can increase the duration. First, just get comfortable with practicing on your own and in unfamiliar spaces. START WITH THE BASICS - Make sure you move the spine. Include a backward bend, a forward bend and a twist. (Ex: High Lunge with Backbend, Half Moon, Hands To Feet, Cobra, Twisting Triangle, Supine Twist, etc.) - Use big muscles. High Lunge, Chair pose and Plank are very powerful postures that will work big muscle groups. This is important because we often sit for long periods which allow muscles such as our abdominals, glutes and legs to get weak. Then if there’s time: - Practice balance. This can be a standing balancing posture and/or an arm balance. (Ex: Standing Hand to Toe or Head To Knee, Balancing Stick, Tree, Palmstand, etc.) - Do breath work. Close your practice with Kapalabhati and/or up to 5 minutes of Alternate Nostril Breathing. If you find that it is helpful to start your practice with breathing as well, start with an exercise like Anatomical Breathing or Standing Deep Breathing. SEQUENCES FOR PRACTICE Eventually, you will feel more comfortable designing your own practice. You will know what your body and mind need in order to be healthy. You will be equally as comfortable practicing for 5 minutes as you are practicing for hours. Until then, try these short and effective sequences. Remember, it's important that you do it often. At the beginning, that is all that matters. VERSION 1 (5 minutes) 1. Plank 2. High Lunge with Backbend 3. Seated Stretching (Janushirasana and Paschimottanasana) 4. Seated Spinal Twist 5. Savasana VERSION 2 (5-10 minutes) 1. High Lunge with Backbend 2. Half Moon with Hands To Feet 3. Chair 4. Palmstand 5. Cobra 6. Seated Stretching (Janushirasana and Paschimottanasana) 7. Seated Spinal Twist 8. Savasana The New York Times just reposted an interview with exercise physiologist Dr. Oliver Jay, asking if there are health benefits associated with sweating, and if more sweat means more benefit. This is a question that hits home to us as yogis who strive to build inner heat, and especially as part of the Bikram and Hot yoga communities where lots of extra heat is added for supposed increased benefits.

“There’s this entrenched idea that it’s good to ‘sweat things out,’” Dr. Jay said, but in fact “sweating, per se, provides no health benefits,” apart from preventing overheating. Exercise, especially vigorous exercise, raises the internal body temperature. "The benefits derive from the exercise itself," not the accompanying rise in body temperature or the sweat that is meant to cool us. Perspiring, in and of itself, does not provide or amplify those effects, Dr. Jay said. That situation doesn’t change if you’re sweating due to a hot environment. “Sweat is sweat,” he said. You will perspire more if the air is humid, he said, because sweat doesn’t evaporate efficiently in humidity, and it’s evaporation that actually cools your body. But you aren’t gaining extra health benefits from drenching your clothing with perspiration. CONSIDERING "HOT" YOGA We got our start in Bikram's class, where the temperature is 105 degrees and you sweat like crazy. There is a continuing trend toward making yoga hot to induce more sweating and increase muscle flexibility (which largely happens through numbing the nervous system, but that's another story). Also there is the "sauna therapy" argument, that when exposed to high temperatures the heart rate increases and the blood vessels dilate, improving cardiac and vascular function. There is new research that practicing yoga in high heat may have a positive impact on cholesterol levels. Contrarily, there is new research that many of the vascular benefits of yoga and stretching are gained at room temperature just as well as in a heated room. CONCLUSION? There are 3 main arguments for practicing yoga or exercising in the heat: 1) increased effectiveness of the exercise, as indicated by rise in body temperature and amount of sweat; 2) increased mobility and flexibility; and 3) benefits to the cardiac and especially vascular system. Argument #1 is simply not true. An exercise is not more beneficial when done in heat, and more sweat - even higher body temperature - does not mean more benefit (see the NY Times article). Argument #2 is a double-edged sword. Heat-induced flexibility may be beneficial to certain parts of the population, like the elderly or injured, but it is detrimental to those who are already flexible, encouraging hyper-mobility. For the general public it's a toss-up. Argument #3 is a good one, and it's gaining clarity with each passing study. Pure Action is funding research to try to tease out the vascular benefits that may come from heat without yoga, those that may come from yoga without heat, and those that are accentuated when the two are put together. In the early texts, the posture called Padmasana (Lotus Posture) is taught in two different ways.

In the Dattatreyayogashastra, the earliest text to describe hathayoga, Padmasana is instructed as the single most important posture. "Turn the soles of the feet upward and carefully place them on the thighs. Put the hands in the lap and turn them upwards in the same way. Then focus the eyes on the tip of the nose, lift up the base of the uvula with the tongue, put the chin on the chest and, slowly inhaling as much as possible, slowly fill the abdomen. Then slowly exhale as much as possible. This is said to be the lotus posture. It destroys all diseases and is hard for anyone to attain; it is attained by the wise man in the world." (Dattatreyayogashastra, verses 35-38) This version is similar to what we call Padmasana (Lotus Posture) today: Bound legs and relaxed arms. It is worth noting that this is not considered an easy posture. It "is hard for anyone to attain." This posture can take years to perfect. The second version of Padmasana is what we call Bound Lotus today, performed by wrapping the arms behind the back and holding onto the toes. Some of the earliest texts teach the posture this way, simply calling it Padmasana. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika, an encyclopedic compilation of practices, instructs the posture as follows: "Place the right foot on the left thigh and the left foot on the right thigh, and grasp the toes with the hands crossed over the back. Press the chin against the chest and gaze on the tip of the nose. This is called the Padmasana, the destroyer of the diseases." (HP 1:46) This "bound" version of the posture is quite common in old texts, at least as common as the un-bound version. The main purpose of traditional hathayoga is to preserve the essence of life, called bindu. It was thought that bindu dripped down from a place in the head and was burned up by the digestive fire in the abdomen. As we get older, our supply of bindu runs out and we age. By preserving bindu we can therefore lengthen our lives. The concept of bindu has faded in the modern era as the focus on physical fitness and western anatomy has grown.

There are two methods to conserve this essence: 1) tipping the body upside down, a technique called viparitakarani (inversion), and 2) drawing bindu upward by placing the breath into the "central channel." These two methods inform many of the practices that we do in yoga. VIPARITAKARANI MUDRA Viparitakarani is often translated as "inverted action," "the reverser" or simply "inversion." The only real instruction we get from old texts is to place the head below the abdomen. This means that Headstand, Shoulderstand and the mudra called viparitakarani qualify. Its goal is to halt the effect of gravity which pulls bindu downward. THE CENTRAL CHANNEL Techniques for drawing bindu upward in the central channel of the body are called mudras. There are 10 or 11 mudras in traditional hathayoga, some of which have been converted into asanas and some of which have been forgotten. They are usually done seated, with pressure from one or both heels on the perineum, and some sort of breath control. This is thought to prevent bindu from falling down and even draw it upward. As the centuries progressed, the concept of bindu was largely replaced by the concept of kundalini, a powerful energy that lies dormant at the base of the spine. The same techniques are used to "awaken" this energy and draw it upward, much like they did for bindu. At its core, an asana sequence is a general yoga prescription designed for many people (as opposed to the traditional prescriptions that are tailored for each individual). Instead of making something perfect for each unique person's fitness level and goals, a general sequence makes each person adjust to it.

A sequence takes into account the general health of the individuals that are likely to come to class. For the most part, nothing taught is too complicated or dangerous in a general class. That means it will be beneficial for the majority of people who take the class. Western cultures have gotten around the issues that this causes by using modifications when necessary in asana classes. For example: Someone who cannot balance can hold onto the wall while attempting a posture. Also, advanced students may "up-level" a posture to bring it to their level of ability. In this way, each student can approximate a personalized practice while doing the same practice as the rest of class. There are pros and cons to the Western approach of sequenced yoga classes. PROS: 1. There's no consultation or one-on-one time required. Any prospective yogi can come in and take class with no preparation. 2. A brand new teacher can get through a class without needing to identify and address individual issues. 3. If the sequence is set already, a teacher doesn't need to come up with what they are teaching. 4. This approach can potentially provide a communal feel, as everyone is taking part in the same actions. CONS: 1. Students cannot progress at the same rate they would with individual attention. They are most likely not pushed as much as they could be in some areas, and are pushed too hard in others. 2. Teachers may be able to get by without continuing to develop their own education since they can "get through a class." This often leads to teacher burnout as well. 3. Without knowing a student's physical condition, a teacher may instruct something that is potentially dangerous for the student. 4. Large parts of the population are underserved. Old, injured, kids, etc. don't often come to class, because they need special attention and the classroom environment doesn't provide that. Just as yoga in the West evolved from its prescriptive tradition, it will continue to change based on cultural values and the systems in place. A lot of people in our Western culture suffer from back pain. It often comes from spending so much time sitting in chairs, in cars and on sofas. The muscles of the back become weak at the same time as the hips and legs become tight. Most back pain can be eased by strengthening the back and stretching the hips. The postures in this sequence are intended to do just that. They lengthen the spine, pelvis, hips and legs, and they strengthen the back.

It is a common misconception that stretching the back will relieve back pain. Generally, the back is already too loose and weak, so stretching can irritate the problem and even make it worse. This sequence takes about 30 minutes to do. Excerpt from the Beginning Practice Manual. Shavasana (Corpse Pose) is fundamental to modern yoga and has been essential for several hundred years. But it did not start as an asana, and its earliest iteration wasn't even technically part of hathayoga.

The earliest instruction describes this practice as part of layayoga or the "Yoga of Dissolution," in which we strive toward "dissolution of the mind." At this point in history (12th century) the techniques of layayoga are separate from hathayoga and include meditating on emptiness, staring at the tip of the nose and staring between the eyebrows. You may recognize some of these techniques from modern yoga, especially the focused gaze which is now commonly referred to as drishti. Another technique of layayoga is as follows: "Lying supine on the ground like a corpse is said to be an excellent dissolution. If one practices in a place free from people while relaxed, one will achieve success." (1) You will recognize this as the practice that is later appropriated into hathayoga and called Shavasana. A few hundred years later hathayoga has become a larger system, full of outside techniques including some from layayoga. By the time the Hatha Pradipika is published, the practice of lying on the ground and stilling the mind is labeled as an asana: "Laying down on the ground, like a corpse, is called Śava-āsana. It removes fatigue and gives rest to the mind." (2) The practice technique is similar to the earlier method from layayoga, with new emphasis on physical elements like fatigue and slightly less emphasis on dissolving the mind. As modern culture has become more hectic and stressful, the elements of relaxation have become central to the practice of Shavasana. A NOTE ON PRONUNCIATION The Sanskrit spelling of this word is śavāsana. The letter ś with the accent mark above is pronounced like "sh." So the truest way to pronounce this word is shavasana (shuh-VAH-suh-nuh). Often the word is written in english as savasana or even śavāsana, and it is easy to mispronounce the first letter as the letter "s." 1. Dattatreya's Discourse on Yoga, trans. James Mallinson, 2013, verse 24-25. 2. Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Chapter 1, verse 34. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed