|

It's easy to find things that pique our interest. We see or hear about something new—a new posture, sport, skill, craft or hobby. We think, "That would be good for me!" Or, "I might like that."

Soon, that initial excitement starts to fade. But, committed to the idea of our new passion, we still gather equipment, books, videos and anything else that we think might help us develop our new curiosity. Then those things sit there. The how-to books are in a pile, the equipment in a corner. Now we are left with a different type of wanting. This is not the desire to actually do or learn, but the want to want to do it. Now we have a choice: use discipline or move on. We can either double down and do the activity anyway, despite our lack of enthusiasm, or we can give it up and move on to something else. Either can be the right answer. It just depends on the goal. To determine which answer is the best one, we should consider the why. When it comes to a yoga practice, the why is very important. It is not a good reason to take up a yoga practice if we just want to see ourselves as a yogi, or have others see us this way. It's easy to get caught up in the idea of appearing spiritual without having the desire to actually walk the path. This is one reason for wanting to want to practice: we like the idea of what it would mean, but don't want to actually do the work. There may be other simpler reasons for wanting to want to practice. It could be that we simply feel tired and need to rest. But the desire to appear as though we practice yoga is important to be aware of. In this case, it may be better to give up the practice entirely. If our desire to practice yoga comes from the desire to strengthen our egoic self, it may be a more yogic action to give up yoga.

0 Comments

Nowadays, ujjayi is a term that is often used in yoga classes. It is said that ujjayi creates a snoring sound, focuses the mind, slows the breath, heats the body, or is a constriction in the throat. Let's examine ujjayi from a historical lens and see if these ideas can be supported. HATHA YOGA'S UJJAYI In the 15th-century text the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP), the instructions for ujjayi are as follows: Close the mouth. Slowly draw the breath through both nadis so it resonates from the throat to the heart. Form the kumbhaka as before. Exhale the prana through the Ida. This kumbhaka called Ujjayi can be done walking or standing. It removes phlegm diseases in the throat, increases digestive power in the body, and destroys dropsy and diseases of the nadir and of all bodily constituents. (2.51-53) There are quite a few terms that may be confusing, but essentially this instructs the practitioner to inhale through both nostrils and exhale out of the left side. This is not what we have come to know as ujjayi today, in which we exhale through both nostrils or even out the mouth. However, as we will see, ujjayi with the exhalation out the left nostril is a consistent instruction up until very recently. The exact same passage from the HYP is found in the Hatharatnavali from the 17th-century. This translation states that we should breathe "with a frictional sound" rather than using the word "resonates" as found in the HYP translation. Either of these instructions could support the idea that ujjayi is practiced with a snoring or whisper sound. Another text of hathayoga, the Gheranda Samhita states: Draw in air through both nostrils and hold it in the mouth. After drawing it through the chest and throat, hold it in the mouth again. After rinsing the air around in the mouth, bow the head, perform Jalandhara, and hold the breath for as long as is comfortable. After performing the Ujjayi kumbhaka, the yogi can succeed in everything he does. (5.64-66) Here we have instructions to breathe in through both nostrils and move the air around in the mouth. However, the next passage is potentially where the mix-up happens. The instructions then say to "perform Jalandhara". The instructions for Jalandhara mudra are to "contract the throat and put the chin on the chest." We would argue this does not mean "constrict" the inside of the throat, but rather contract the muscles on the front of the throat to put the chin on the chest. (This is in line with the common understanding of jalandhara.)

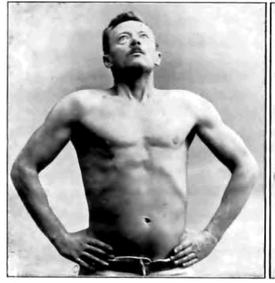

Ujjayi requires Abhyanatara Kumbhaka, that is Kumbhaka practised after deep inhalation. The first thing that demands our attention is the complete closure of the glottis. This thoroughly shuts off the passage to and from the lungs. The second thing is the practice of Jalandhara-Bandha and the third is shutting of the nostrils.....When Kumbhaka is to end, first relieve the pressure from the left nostril, then unlock Jalandhara-Bandha and afterwards partially open the glottis. Rechaka is done through the left nostril. Here again we have the instruction to hold the breath after the inhale. The throat lock is applied to keep the air in, and here the nostrils are also closed. Again, exhalation is done through the left nostril. We see the move toward teaching the throat constriction with anatomical language. Kuvalayanada clearly states to close the glottis. In 1931, Swami Shivananda instructs: Inhale through both nostrils in a smooth uniform manner till the breath fills the space from the throat to the heart with a noise. Retain the breath as long as you can comfortably do it and then exhale slowly through the left nostril by closing the right nostril with your right thumb. Shivananda writes that ujjayi "removes the heat in the head" yet he also says that it increases the gastric fire. Whether this supports removing heat or building heat is up for debate. Either way, this is the only mention of heat in all of the sources examined here. It is no surprise that Shivananda's disciple Swami Vishnudevananda in his popular book The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga instructs the practice in the same way. Vishnudevananda quotes the HYP. The benefits he lists for ujjayi suggest it removes "phlegm from the throat" and prevents a handful of diseases. He says nothing about internal heat. In 1962, Patthabi Jois mentions ujjayi only in a list of pranayamas that pregnant women can do in Yoga Mala. There is no description given.  Iyengar teaching ujjayi in Light On Yoga - 1966 (p. 442) Iyengar teaching ujjayi in Light On Yoga - 1966 (p. 442) In Light On Yoga from 1966, Iyengar teaches ujjayi as follows: Take a slow, deep steady breath through both nostrils. The passage of the incoming air is felt on the roof of the palate and makes a sibilant sound (sa). This sound should be heard. Fill the lungs to the brim....Hold the breath for a second or two....Exhale slowly, steady and deeply, until the lungs are completely empty. As you begin to exhale, relax your grip on the abdomen. Iyengar instructs that mula bandha is to be used and states that "ujjayi pranayama may be done without the Jalandhara Bandha even while walking or lying down". Iyengar removes the instruction to exhale out the left side only, but he maintains the use of jalandhara bandha and emphasizes the sound of the breath. Though Iyengar shortened the retention to just a few seconds, there is still a retention. It is not a smooth or even breath cycle. Ujjayi is rarely referred to in the Ghosh lineage. In Gouri Shankar Mukerji's 84 Yoga Asanas from 1963, it appears only in mention of additional pranayama practices and is one in which "longer pauses are inserted between the inhale and exhale". RECENT DESCRIPTIONS OF UJJAYI IN YOGA Very recent passages such as David Swenson's in his 1999 book Ashtanga Yoga explain: This unique form of breathing is performed by creating a soft sound in the back of the throat while inhaling and exhaling through the nose....The main idea is to create a rhythm in the breath and ride it gracefully throughout the practice. This sound creates a mantra to set the mind in focus. In 2006, Gregor Maehle writes: Ujjayi pranayama is a process of stretching the breath, and in this way extending the life force. Practicing it requires a slight constriction of the glottis....Start producing the ujjayi sound steadily, with no breaks between breaths. These passages don't refer to creating internal heat, but the sound created is given deep importance. It is surprising to see ujjayi become an even breathing technique. However this makes more sense if we look at descriptions of breathing techniques in systems outside of yoga. BREATHING IN PHYSICAL CULTURE & GYMNASTICS JP Mueller was a Danish instructor of gymnastics and physical culture in the early twentieth century. Mueller's "System" manuals deeply informed the practices of modern physical culture, and in turn, modern yoga. (For more on this see Mark Singleton's Yoga Body.)  "The Correct Pose for Inhalation - Front View" JP Mueller's My Breathing System - 1914 "The Correct Pose for Inhalation - Front View" JP Mueller's My Breathing System - 1914 Instructions in Mueller's My Breathing System are more in line with today's descriptions of ujjayi which emphasize rhythmic breathing. Mueller writes: I do not advocate any breath-holding exercise. It must also be remembered that it is not only the action of the lungs and heart which is disturbed by holding the breath. What stimulates the stomach, liver, bowels and intestines is just the internal massage produced by the movements of the lower ribs and the diaphragm, when full, deep, correct breathing is performed. Furthermore, there is emphasis on the importance of rhythmic breath for vitality as early as 1892. Genevieve Stebbin's writes in her book Dynamic Breathing and Harmonic Gymnastics: ...the truth that deep, rhythmic breathing combined with a clearly formulated image or idea in the mind produces a sensitive, magnetic condition of the brain and lungs, which attracts the finer ethereal essence from the atmosphere with every breath, and stores up this essence in the lung-cells and brain-convolutions in almost the same way that a storage battery stores up the electricity from the dynamo or other source of supply, and is held in suspension amid the molecules forming the cellular tissue as a dynamic energy, possessing both mental and magnetic powers, always ready for use whenever required. It is here that we see the distinct link of breath to cultivation of life force in the body. Where hathayoga texts suggested ujjayi removes phlegm, in sources outside of yoga we see the focus on building vitality. This is still common in yoga classes today and is another display of the outside influence on modern yoga. CONCLUSIONS Early- to mid-20th-century conceptions of ujjayi in yoga instruct retention of the breath. Most instruct the exhalation out of the left nostril, with the exception of Iyengar. While there is a sound and constriction of the throat associated with the practice, that constriction often means jalandhara bandha, or tucking the chin to the chest. There is no mention to creating internal heat except when Swami Shivananda mentions gastric fire and removing heat from the head. With the exception of Iyengar, all of these descriptions follow the hathayoga instructions quite closely. Ujjayi has undergone quite a transformation in the centuries it's been taught. If we look to instruction on breathing practices from systems outside of yoga such as physical culture and gymnastics, we get a glimpse at how ujjayi evolved into what it is today. Sources: Akers, Brian. 2002. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika. (p. 45-46)

Gharote, Devnath & Jha. 2014. Hatharatnavali (p. 46) Iyengar, BKS. 1966. Light On Yoga. (p. 442) Jois, P. 1962 (in Kanada, 1999 in English ) Yoga Mala. (p. 67) Kuvalayananda, S. 1931. Pranayama, (p. 76-78) Maehle, G. 2006. Ashtanga Yoga. (p. 9) Mallinson, J. 2004. The Gheranda Samhita. (p. 62, 105) Mukerji, GS. 2017. 84 Yoga Asanas. (p. 3) Mueller, JP. 1914. My Breathing System. (p. 17) Shivananda, S. 1931. Yoga Asanas. (p. 85) Singleton, M. 2010. Yoga Body Stebbins, G. 1892. Dynamic Breathing and Harmonic Gymnastics. (p. 53) Swenson, D. 1999. Ashtanga Yoga. (p. 9) Vishnudevananda, S. 1960. The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. (p. 249) We expect to get better at what we practice. When we don't, it becomes difficult to carry on. We can easily get frustrated, disheartened or fed up all together.

When it comes to posture practice, there are three main reasons why our postures may not be improving despite our best efforts. Let's explore them one by one. MAKING SHAPES A posture is not simply a shape. It is a set of muscular engagements and relaxations. When done correctly, certain parts of the body are exerting effort while other parts relax. The problem is that we can make shapes that resemble the posture, without building the skills to do the posture correctly. What we do may look like the posture, but in fact we are teaching the body to do the wrong thing. To make matters worse, the more we practice incorrectly, the further from the posture we get. More effort takes us in the wrong direction. A good example of this is a standing backbend. If we lean backward, we may resemble the shape of a backbend. But what is engaging and what is relaxing makes all the difference. If our abdomen has engaged, we are not in a backbend. In this case, we are actually using the muscles of forward bending! If our back is engaging, we are moving in the right direction. If we practice in the right direction progress is inevitable. STRETCHING NOT STRENGTHENING The body relaxes when it has the stability to do so. Tension, or tightness, is a result of weakness. If a joint is weak it will be unstable. If it is unstable, the areas around it cannot stretch or relax without making the joint susceptible to injury. The body does not want to risk injury, so it would prefer to maintain tension in order to keep itself safe. If we want to gain flexibility or remove tension, we have to strengthen our muscles. Once we have strength in the body, it will be safe for the joints to move in a greater range of motion. This greater range of motion is what we call flexibility. LACKING UNDERSTANDING We must know what we are trying to accomplish. If we are practicing in the wrong direction - even if that direction is good for someone else - we will never get where we are trying to go. If a baseball player works on dribbling a basketball it will not help them. In the same way, we have to practice the things we want to get better at. If we are trying to get better at a certain posture, we have to practice that posture. The more we understand the purpose of each posture, the better we can tailor our effort toward accomplishing that purpose. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed