|

Over the past few years, we have researched the origin and evolution of several postures and practices in this lineage. We thought we would gather them all together in one post, with convenient links.

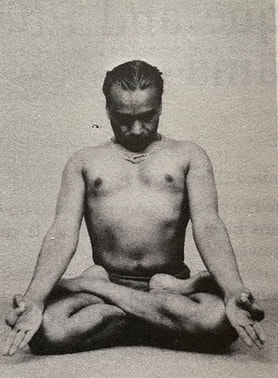

Probably the most significant single piece of research we've done was organizing the postures taught by Bishnu Charan Ghosh and several of his prominent students. We found 113 total postures, with 27 of them that seem to have been central during Ghosh's lifetime. The full list is here, in all its detailed glory. Of course, many of the postures in modern yoga trace back to the late hathayoga era, as physical practice was blossoming. It is noteworthy that all 10 of the older postures in Bikram's class were in the Gheranda Samhita, a text thought to be from Bengal (where Kolkata is). Bow Posture, a staple of modern yoga, seems to have transformed in the 1920s. The posture dhanurasana is explained in hathayoga texts, but it was probably a different posture. Then, the modern backbend came became popular, and is now one of the most recognizable yoga postures. Triangle Posture came into modern yoga in the 1920s, probably under the influence of gymnastics and calisthenics. But it wasn't until the 1970s that Bikram Choudhury transformed the posture into a deep sideways lunge that resembles a bodybuilding pose. Tree Posture is old by any measure. But it has curiously changed names several times, called anything from ardha chandrasana to ardha padasana, vrikshasana to tadasana. Modern Camel Posture, ushtrasana, seemingly came out of nowhere in the 1930s before completely overtaking the older version in the 1960s. Camel Posture has never looked back! Standing Bow Posture is such a new phenomenon that it is hard to even trace where it comes from. Probably some combination of dance and gymnastics, and probably from the south of India. Bikram Choudhury seems to have evolved this posture into its modern form.

0 Comments

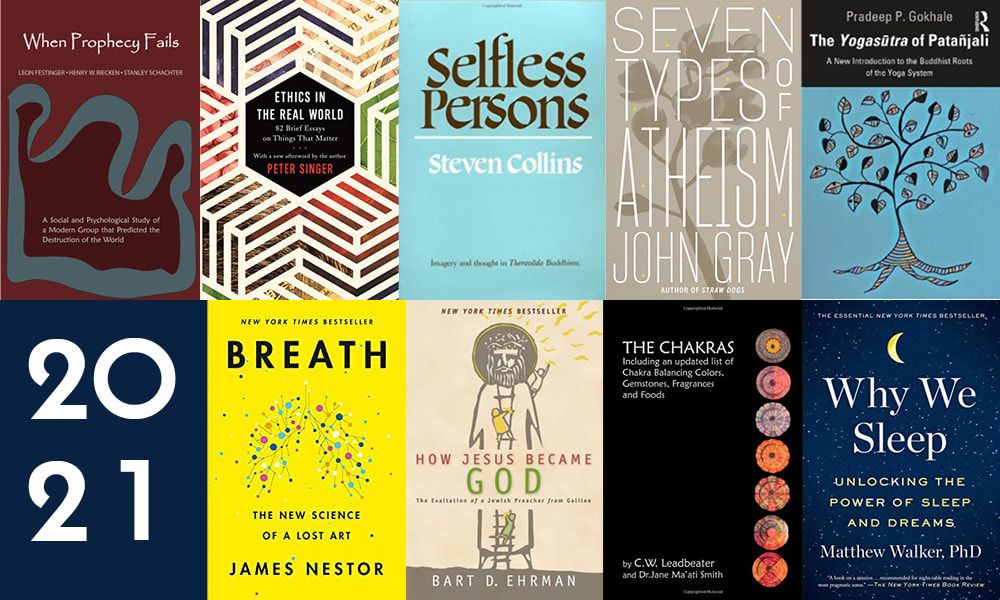

Gosh I love to read! Every book is an opportunity to see the world from a new perspective, to learn something from an expert, or to peer through a window to a different time and place. Here is a short list of books I read this year that had a profound impact on me. They are not new books. In fact, some of them are quite old. But they are all valid, and they meant a lot to me this year. WHEN PROPHECY FAILS by Festinger, Riecken and Schachter This work of social psychology from the 1950s dives into the mentality, actions and beliefs of a UFO cult. But it is so much more than that: an exploration of how our minds react when we may be wrong about something we really believe in. The authors build the case that, even when we are confronted with evidence that we are wrong, we essentially double-down in our beliefs. It is a chilling conclusion — that humans are sometimes immune to changing our minds. As the authors write, "when people are committed to a belief and a course of action, clear disconfirming evidence may simply result in deepened conviction". After reading this book, it is hard not to see this phenomenon all around us in the world today. ETHICS IN THE REAL WORLD by Peter Singer Ethics and morality have become especially important to me this year. Perhaps it is due to the ongoing pandemic and the acute awareness of how my actions can impact others. I stumbled upon this book, which contains 82 short essays about various ethical conundrums — from geopolitics to religious freedom, eating meat to climate change — and thought it would be a good overarching introduction. It is. Singer writes with remarkable clarity about ethical issues of all sorts. And the brevity of the essays means that nothing is belabored. SELFLESS PERSONS by Steven Collins This scholarly dive into the Buddhist concept of non-self is deep, complex and absolutely stunning. The idea that there is no eternal Self can be confounding and frustrating, especially when compared to other systems that insist upon its existence. The importance of non-self is summarized best in Collins's introduction: "this belief in a permanent and a divine soul is the most dangerous and pernicious of all errors, the most deceitful of illusions, that it will inevitably mislead its victim into the deepest pit of sorrow and suffering". SEVEN TYPES OF ATHEISM by John Gray I'm a sucker for an analysis of human spirituality in all its subtlety, diversity and contradiction. Gray's book does not disappoint. He begins by defining an atheist: "anyone with no use for the idea of a divine mind that has fashioned the world...It is simply the absence of the idea of a creator-god". This leaves a lot of room for variation in beliefs about the nature of the universe, creation and human spirituality. Gray systematically explains seven distinct forms of atheism that have been embraced throughout history. A book of remarkable clarity and exposition that illuminates the ways we see ourselves and the world. THE YOGASUTRA OF PATANJALI: A NEW INTRODUCTION TO THE BUDDHIST ROOTS OF THE YOGA SYSTEM by Pradeep P. Gokhale I don't know how many different translations and explanations of the Yoga Sutras I have read. Dozens. Many are confused or confusing, and scholars are increasingly aware of the compiled nature of the text, and how it shows influence from a handful of other systems of thought. Buddhism is among these influences, but deep dives into the Buddhist roots of the Yoga Sutras require a rare combination of expertise. With this new research, Gokhale has provided a huge step forward in our understanding of the philosophical and linguistic roots of the Yoga Sutras. He analyzes works of Abhidharma Buddhism and shows how they explain many aspects of the Yoga Sutras better than traditionally accepted narratives. This is a scholarly work, full of difficult history and terminology, but worth it for anyone with a serious interest in yoga history or the Yoga Sutras in particular. WHY WE SLEEP by Matthew Walker This book was recommended to us by several people over the past few years until it became impossible to ignore. And it was worth it! We even wrote a blog about it. The book begins with the obvious-in-hindsight revelation that sleep is vital. It is not a passive state of nothingness that can be shortened or neglected. Rather, it is a very active state for many systems of the body, especially the brain. Walker explains the structure of sleep and its impact on things like our memory, physical health and even physical coordination. This is a book with practical, everyday implications that can make anyone's life better. THE CHAKRAS by C.W. Leadbeater Earlier this year, as we were doing research for a workshop series on the Yogic Body, we read a handful of books about the chakras from the early 20th century, including this one. Leadbeater was a prominent Theosophist, a highly influential group that shaped modern conceptions of yoga and spirituality. This book from 1927 is remarkable as a vivid capsule of the time. Leadbeater claimed that he could see the chakras, and he painted them beautifully. I find these paintings to be among the most remarkable elements of 20th century yogic history because, aside from being lovely, they show the break-neck speed of change in conceptions of the yogic body. Here, in the 1920s, there were seven chakras associated with parts of anatomy. But they were not yet rainbow in color nor linked with psychological traits as they came to be in the 1970s. HOW JESUS BECAME GOD by Bart D. Ehrman Along with our study of yoga history and the history of religion in general, both Ida and I have been increasingly reading about the history of Christianity. It is fascinating for the same reason as all history — our ideas change rapidly along with the cultural needs of the time. This book by Ehrman explores the early centuries after the death of Jesus, and how the story of Jesus changed, turning him from a preacher or even a prophet into the only son of God himself who rose from the dead. It is full of scriptural quotations and explanations alongside historical analysis. And it is quite readable, which is not something one can often say about a work of scholarship like this. BREATH by James Nestor

I never thought someone could write a compelling story about breathing, something we all do thousands of times each day. But Nestor has crafted a surprisingly interesting narrative around his own research into breathing anatomy, physiology and history. Where it falls short of a scholarly history or a medical anatomy text, it more than makes up with its humor and readability. This is a book that anyone can and should read to have more understanding and appreciation of the most fundamental function of life — breathing. Navigating the yoga world can be frustrating. There are so many different styles and so much history underpinning the practices. Not everyone thinks that yoga's history is important, but many find value in the traditions. If you are someone who cares about — or wants to care about — yoga's history and traditions, here are four important concepts, explained as simply as we can.

VEDA The word Veda (pronounced vay-duh) means 'knowledge'. This is the name given to the sacred scriptures of Brahmanism/Hinduism. Sometimes these traditions (like Hinduism) are even called Vedic religions because they are largely defined by their reverence for these holy books. The Veda is considered to be revealed knowledge, meaning that it was not written or composed by a human. It was simply written down by humans, sages with special abilities of sight. The knowledge within is thought to be universal, eternal wisdom, something akin to 'the word of God'. UPANISHAD The Upanishads are the last group of books in the Veda. It can help to think of them like the New Testament of the Christian Bible. They are grouped with the rest of the Veda as revealed knowledge, but they present a somewhat different view of the world and spiritual effort. The Upanishads introduce an internal spiritual path, where rituals are carried out in one's own heart rather than externally. This is also where the concept of 'yoga' is introduced, an inward linking of one's awareness to the infinite consciousness within. YOGA Yoga means 'linking' or 'harnessing'. In the Upanishads, where the concept of a spiritual practice named 'yoga' first arises, it refers to linking our awareness within rather than to the world outside. At other times, in more God focused traditions, yoga can refer to linking one's awareness or being with God. In medieval systems of hathayoga, abstract concepts of non-duality became common. Much like the concept of yin and yang, where two opposing forces combine to create balance, yoga could mean the balance of male-female, sun-moon, hot-cold, etc. In this way, many people now define yoga as 'union', which usually refers to some sort of balance or non-duality. In the modern West, most will relate yoga to a physical routine of stretching and relaxation. This type of yoga is pretty new, about a hundred years old. HATHA Hathayoga developed about a thousand years ago. It was a method of using the body to force an effect on consciousness. This is probably why it was called hatha, which means 'force'. A more poetic explanation of hatha developed a little later: it is the union of masculine (ha) and feminine (tha). Much like 'yoga', above, this understanding appeals to balance and unity. In the last couple hundred years, hathayoga has taken on the meaning of 'any physical practices, like postures or breathing'. As such, a lot of modern yoga refers to itself as hathayoga. But modern yoga is a pretty new phenomenon, quite different in practice and belief from the hathayoga of 500 years ago. So most scholars hesitate to call modern yoga hathayoga, instead adopting other labels, like neo-hathayoga or modern postural yoga. Nowadays, ujjayi is a term that is often used in yoga classes. It is said that ujjayi creates a snoring sound, focuses the mind, slows the breath, heats the body, or is a constriction in the throat. Let's examine ujjayi from a historical lens and see if these ideas can be supported. HATHA YOGA'S UJJAYI In the 15th-century text the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP), the instructions for ujjayi are as follows: Close the mouth. Slowly draw the breath through both nadis so it resonates from the throat to the heart. Form the kumbhaka as before. Exhale the prana through the Ida. This kumbhaka called Ujjayi can be done walking or standing. It removes phlegm diseases in the throat, increases digestive power in the body, and destroys dropsy and diseases of the nadir and of all bodily constituents. (2.51-53) There are quite a few terms that may be confusing, but essentially this instructs the practitioner to inhale through both nostrils and exhale out of the left side. This is not what we have come to know as ujjayi today, in which we exhale through both nostrils or even out the mouth. However, as we will see, ujjayi with the exhalation out the left nostril is a consistent instruction up until very recently. The exact same passage from the HYP is found in the Hatharatnavali from the 17th-century. This translation states that we should breathe "with a frictional sound" rather than using the word "resonates" as found in the HYP translation. Either of these instructions could support the idea that ujjayi is practiced with a snoring or whisper sound. Another text of hathayoga, the Gheranda Samhita states: Draw in air through both nostrils and hold it in the mouth. After drawing it through the chest and throat, hold it in the mouth again. After rinsing the air around in the mouth, bow the head, perform Jalandhara, and hold the breath for as long as is comfortable. After performing the Ujjayi kumbhaka, the yogi can succeed in everything he does. (5.64-66) Here we have instructions to breathe in through both nostrils and move the air around in the mouth. However, the next passage is potentially where the mix-up happens. The instructions then say to "perform Jalandhara". The instructions for Jalandhara mudra are to "contract the throat and put the chin on the chest." We would argue this does not mean "constrict" the inside of the throat, but rather contract the muscles on the front of the throat to put the chin on the chest. (This is in line with the common understanding of jalandhara.)

Ujjayi requires Abhyanatara Kumbhaka, that is Kumbhaka practised after deep inhalation. The first thing that demands our attention is the complete closure of the glottis. This thoroughly shuts off the passage to and from the lungs. The second thing is the practice of Jalandhara-Bandha and the third is shutting of the nostrils.....When Kumbhaka is to end, first relieve the pressure from the left nostril, then unlock Jalandhara-Bandha and afterwards partially open the glottis. Rechaka is done through the left nostril. Here again we have the instruction to hold the breath after the inhale. The throat lock is applied to keep the air in, and here the nostrils are also closed. Again, exhalation is done through the left nostril. We see the move toward teaching the throat constriction with anatomical language. Kuvalayanada clearly states to close the glottis. In 1931, Swami Shivananda instructs: Inhale through both nostrils in a smooth uniform manner till the breath fills the space from the throat to the heart with a noise. Retain the breath as long as you can comfortably do it and then exhale slowly through the left nostril by closing the right nostril with your right thumb. Shivananda writes that ujjayi "removes the heat in the head" yet he also says that it increases the gastric fire. Whether this supports removing heat or building heat is up for debate. Either way, this is the only mention of heat in all of the sources examined here. It is no surprise that Shivananda's disciple Swami Vishnudevananda in his popular book The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga instructs the practice in the same way. Vishnudevananda quotes the HYP. The benefits he lists for ujjayi suggest it removes "phlegm from the throat" and prevents a handful of diseases. He says nothing about internal heat. In 1962, Patthabi Jois mentions ujjayi only in a list of pranayamas that pregnant women can do in Yoga Mala. There is no description given.  Iyengar teaching ujjayi in Light On Yoga - 1966 (p. 442) Iyengar teaching ujjayi in Light On Yoga - 1966 (p. 442) In Light On Yoga from 1966, Iyengar teaches ujjayi as follows: Take a slow, deep steady breath through both nostrils. The passage of the incoming air is felt on the roof of the palate and makes a sibilant sound (sa). This sound should be heard. Fill the lungs to the brim....Hold the breath for a second or two....Exhale slowly, steady and deeply, until the lungs are completely empty. As you begin to exhale, relax your grip on the abdomen. Iyengar instructs that mula bandha is to be used and states that "ujjayi pranayama may be done without the Jalandhara Bandha even while walking or lying down". Iyengar removes the instruction to exhale out the left side only, but he maintains the use of jalandhara bandha and emphasizes the sound of the breath. Though Iyengar shortened the retention to just a few seconds, there is still a retention. It is not a smooth or even breath cycle. Ujjayi is rarely referred to in the Ghosh lineage. In Gouri Shankar Mukerji's 84 Yoga Asanas from 1963, it appears only in mention of additional pranayama practices and is one in which "longer pauses are inserted between the inhale and exhale". RECENT DESCRIPTIONS OF UJJAYI IN YOGA Very recent passages such as David Swenson's in his 1999 book Ashtanga Yoga explain: This unique form of breathing is performed by creating a soft sound in the back of the throat while inhaling and exhaling through the nose....The main idea is to create a rhythm in the breath and ride it gracefully throughout the practice. This sound creates a mantra to set the mind in focus. In 2006, Gregor Maehle writes: Ujjayi pranayama is a process of stretching the breath, and in this way extending the life force. Practicing it requires a slight constriction of the glottis....Start producing the ujjayi sound steadily, with no breaks between breaths. These passages don't refer to creating internal heat, but the sound created is given deep importance. It is surprising to see ujjayi become an even breathing technique. However this makes more sense if we look at descriptions of breathing techniques in systems outside of yoga. BREATHING IN PHYSICAL CULTURE & GYMNASTICS JP Mueller was a Danish instructor of gymnastics and physical culture in the early twentieth century. Mueller's "System" manuals deeply informed the practices of modern physical culture, and in turn, modern yoga. (For more on this see Mark Singleton's Yoga Body.)  "The Correct Pose for Inhalation - Front View" JP Mueller's My Breathing System - 1914 "The Correct Pose for Inhalation - Front View" JP Mueller's My Breathing System - 1914 Instructions in Mueller's My Breathing System are more in line with today's descriptions of ujjayi which emphasize rhythmic breathing. Mueller writes: I do not advocate any breath-holding exercise. It must also be remembered that it is not only the action of the lungs and heart which is disturbed by holding the breath. What stimulates the stomach, liver, bowels and intestines is just the internal massage produced by the movements of the lower ribs and the diaphragm, when full, deep, correct breathing is performed. Furthermore, there is emphasis on the importance of rhythmic breath for vitality as early as 1892. Genevieve Stebbin's writes in her book Dynamic Breathing and Harmonic Gymnastics: ...the truth that deep, rhythmic breathing combined with a clearly formulated image or idea in the mind produces a sensitive, magnetic condition of the brain and lungs, which attracts the finer ethereal essence from the atmosphere with every breath, and stores up this essence in the lung-cells and brain-convolutions in almost the same way that a storage battery stores up the electricity from the dynamo or other source of supply, and is held in suspension amid the molecules forming the cellular tissue as a dynamic energy, possessing both mental and magnetic powers, always ready for use whenever required. It is here that we see the distinct link of breath to cultivation of life force in the body. Where hathayoga texts suggested ujjayi removes phlegm, in sources outside of yoga we see the focus on building vitality. This is still common in yoga classes today and is another display of the outside influence on modern yoga. CONCLUSIONS Early- to mid-20th-century conceptions of ujjayi in yoga instruct retention of the breath. Most instruct the exhalation out of the left nostril, with the exception of Iyengar. While there is a sound and constriction of the throat associated with the practice, that constriction often means jalandhara bandha, or tucking the chin to the chest. There is no mention to creating internal heat except when Swami Shivananda mentions gastric fire and removing heat from the head. With the exception of Iyengar, all of these descriptions follow the hathayoga instructions quite closely. Ujjayi has undergone quite a transformation in the centuries it's been taught. If we look to instruction on breathing practices from systems outside of yoga such as physical culture and gymnastics, we get a glimpse at how ujjayi evolved into what it is today. Sources: Akers, Brian. 2002. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika. (p. 45-46)

Gharote, Devnath & Jha. 2014. Hatharatnavali (p. 46) Iyengar, BKS. 1966. Light On Yoga. (p. 442) Jois, P. 1962 (in Kanada, 1999 in English ) Yoga Mala. (p. 67) Kuvalayananda, S. 1931. Pranayama, (p. 76-78) Maehle, G. 2006. Ashtanga Yoga. (p. 9) Mallinson, J. 2004. The Gheranda Samhita. (p. 62, 105) Mukerji, GS. 2017. 84 Yoga Asanas. (p. 3) Mueller, JP. 1914. My Breathing System. (p. 17) Shivananda, S. 1931. Yoga Asanas. (p. 85) Singleton, M. 2010. Yoga Body Stebbins, G. 1892. Dynamic Breathing and Harmonic Gymnastics. (p. 53) Swenson, D. 1999. Ashtanga Yoga. (p. 9) Vishnudevananda, S. 1960. The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. (p. 249) Two weeks ago, the state of Alabama overturned a 30 year ban on yoga instruction in public schools. Now yoga can be taught in schools there, with a few caveats.

The bill continues the transformation of modern yoga into a secular, physical, health-centric exercise practice, a process that began about 100 years ago in India. As far as the bill promotes health in students, it is to be applauded. But its understanding of the essence of modern yoga is off the mark, which leads to a couple mistaken restrictions, like the exclusive use of the English language. According to the bill, "All instruction in yoga shall be limited exclusively to poses, exercises, and stretching techniques. All poses shall be limited exclusively to sitting, standing, reclining, twisting, and balancing. All poses, exercises, and stretching techniques shall have exclusively English descriptive names. Chanting, mantras, mudras, use of mandalas, induction of hypnotic states, guided imagery, and namaste greetings shall be expressly prohibited." These stipulations come from concerns over the possibility of yoga's inherent religiosity or spirituality. Religious teaching of any kind is not permitted in public schools, and some worry that even non-religious yoga practices are a trojan horse, smuggling Hinduism or Buddhism into the curriculum. At the root of the confusion is a common term: yoga. It can refer to old practices or new, spiritual, religious or physical. The confusion arises when we do not know which are being taught, or when we think they are all the same. The Alabama bill makes this mistake, equating yoga practice with Hinduism. It requires parental permission for any student to participate, including the statement, "I understand that yoga is part of the Hinduism religion.” Let’s look at this misunderstanding in a little more detail. Practices called yoga have been around for thousands of years. For most of history, yoga was spiritual, a practice of linking one's awareness with the eternal soul within, or with a deity. In this way, yoga can be associated with Hinduism. But yoga that is practiced today is different. In the early 20th century, yoga practice became largely physical and focused on health, downplaying or entirely dropping its spiritual and religious elements. According to yoga scholar Mark Singleton, conceptions of yoga in the 20th century are shaped by "modern physical culture, 'healthism', and Western esotericism." In other words, modern yoga is closer to gymnastics than prayer. Even though they share the same name — yoga — modern practice is fundamentally different from earlier spiritual forms. Confusion is common. Most people who do not practice yoga, and even many who do, mistakenly think that the postures and exercises in a yoga class are ancient and inherently spiritual in nature. But most of the stretches and asanas in a yoga class come from calisthenics, gymnastics and dance as recently as the last few decades. As such, they are exercises that look good, feel good and improve our health. Singleton writes, "among outsiders and practitioners alike, there is often little awareness that these modes of [modern] practice have no precedent (prior to the early twentieth century, that is) in Indian yoga traditions.” So it is no surprise that parents and politicians fear inherent Hinduism in yoga, even though little or none exists in its modern iterations. THE SANSKRIT LANGUAGE This same misunderstanding appears in the Alabama bill with regard to language. Though it is not stated explicitly, the insistence on "exclusively English descriptive names" seems to be a way to prevent the use of the Sanskrit language, most likely due to fear that Sanskrit will smuggle in Hinduism or Buddhism. But non-English languages are fundamental parts of many disciplines. In music, every student learns the Italian allegro, andante, forte and piano, words meaning fast, slow, loud and soft. And biologists often use Latin to classify species like homo sapiens. Some yoga postures are named after Hindu deities. For example, Hanumanasana is named after the god Hanuman; Virabhadrasana is named after Virabhadra; Vasishthasana is named for Vasishtha. These names and their deities are rightfully forbidden from public schools, just as any mention of Moses, Jesus or Mohammed would be. But other postures are named for secular objects like shapes and animals. There is Trikonasana, the Triangle Posture; Vrikshasana, the Tree Posture; Bhujangasana, the Cobra Posture, among countless others. Surely these names do not infringe upon religious freedom or inherently imply Hindu worship, whether in English or Sanskrit. And there is no harm in learning the Sanskrit word for tree. At its core, then, the new bill in Alabama continues the secularization, exercise and health focus of modern yoga. In this way, it isn't terribly different from the twentieth-century innovations of Vivekananda or Yogendra, who removed unattractive traditional beliefs in favor of modern ones. — Singleton, Mark. 2010. Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford University Press. The issue of cultural appropriation has been troubling yoga lately. Did the West steal yoga from India? Does India own yoga? Do Indians naturally and inherently understand yoga because of their cultural heritage? Is it in their blood? Some have suggested that non-Indians should not teach yoga.

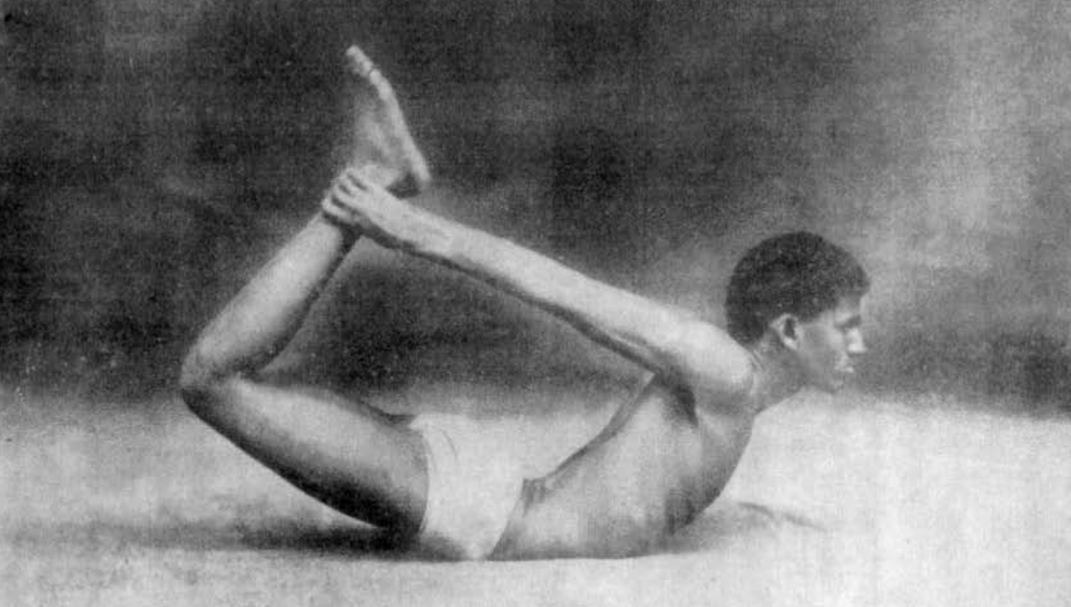

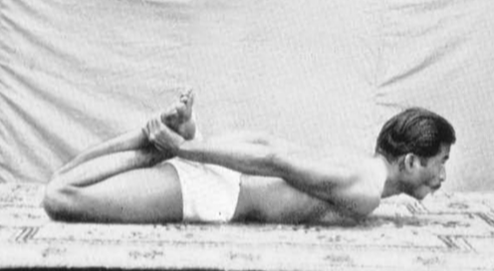

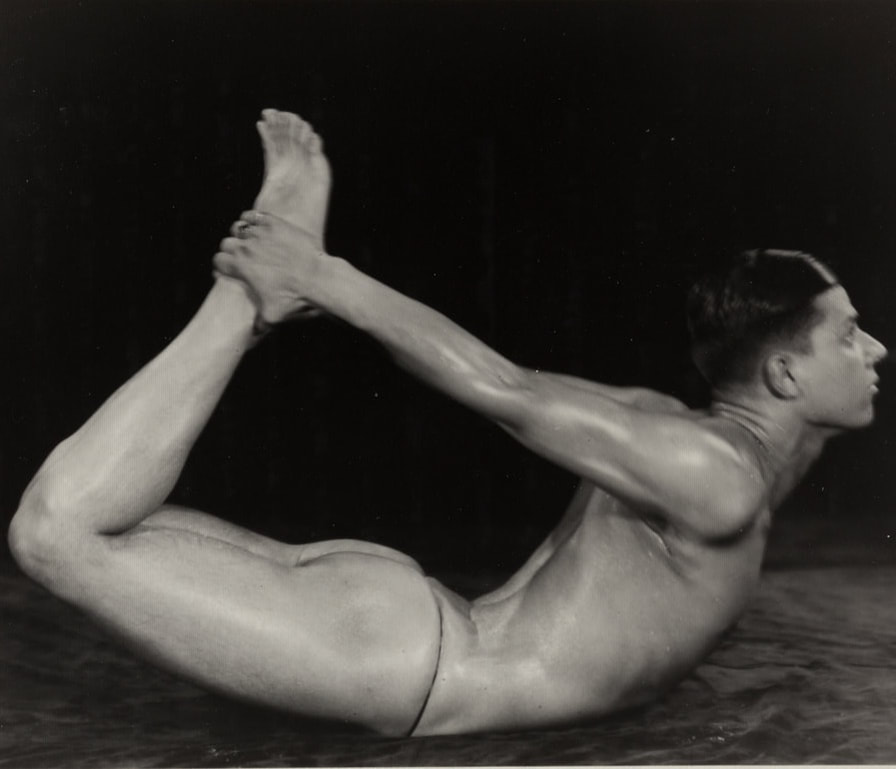

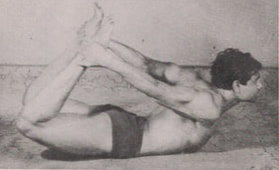

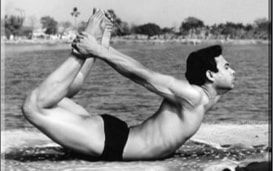

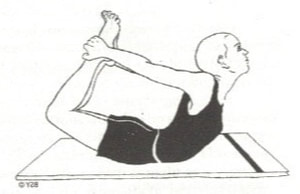

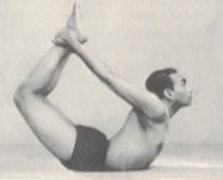

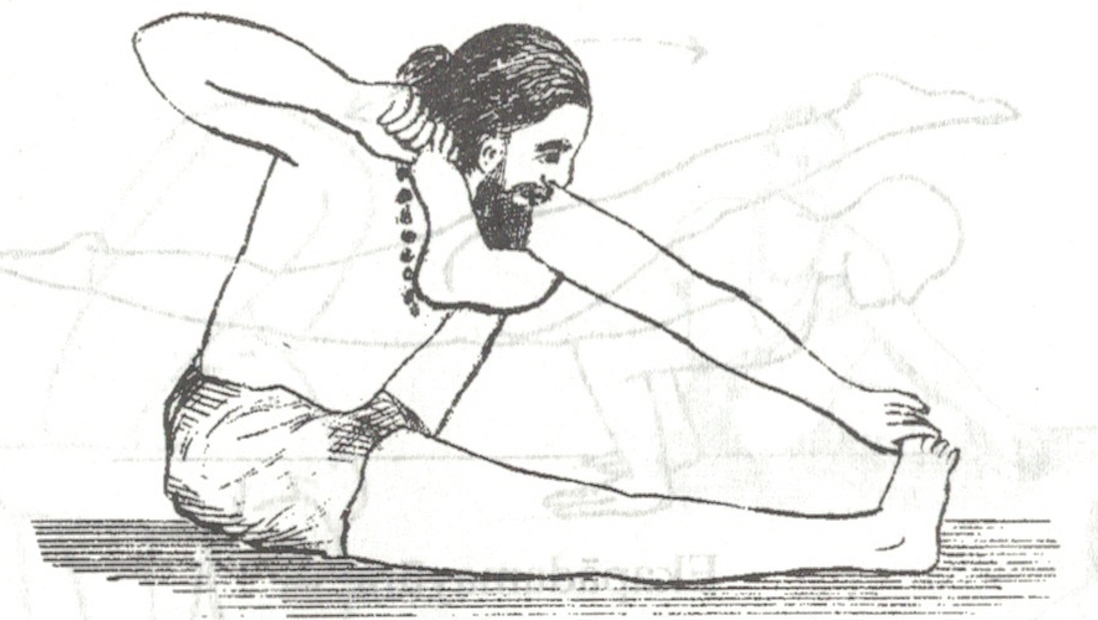

Three elements are worth stating briefly before we answer the central question. First, any claim that intelligence, knowledge, understanding or ability can be judged by a person’s heritage or race should be recognized for what it is. At best it is nationalism, at worst it is racism. With yoga, the sentiment is understandable on several levels. Yoga has become a billion dollar industry beyond India's borders. Furthermore, much about what modern yoga is today shifted drastically while India was under British rule. The desire to reclaim a popular system as one’s own is relatable. Yoga, like many other trades, practices or professions can be passed down generation to generation. At a young age, the next in line takes over the family business. They grow up around it and learn everything there is to know about it from the older generation. This is different. This is closer to a master/apprentice or guru/disciple relationship. In this case, the second generation will have knowledge and understanding that the outside world won't have. But this is because of the immense time spent learning and studying the craft. If the child of an expert chooses not to study or practice yoga for example, they cannot expect to know a great deal about it even if they are directly related to an expert. Second, heritage of a subject or art form in a country does not give that country exclusive ownership of it. Ideas and goods have been traded internationally for thousands of years, evolving as they go. The Chinese cannot claim the exclusive right to make paper, the Babylonians mathematics, nor the Indians yoga. Third, we need to be clear about what we mean by 'yoga'. This may seem obvious, but it is nuanced enough to deserve a little explanation. There is no doubt that yoga originates in India. The ancient Katha Upanishad is its first known explanation. For thousands of years, yoga was a spiritual practice of uniting one’s awareness with an eternal spirit within, or with a deity. In the twelfth century, a practice with bodily elements developed, called hathayoga, the 'yoga of force'. But the goal was the same, to create spiritual unity with a higher being. In the early twentieth century, this changed drastically. Over the course of a couple decades, yoga was refashioned as a modern, scientific, physical practice for health. Modern yoga represents a fundamental break from the older spiritual iterations. It shows influence from European physical cultures like gymnastics and calisthenics. As such, even India’s claim as the singular authentic source of modern physical yoga is worthy of healthy debate. But let’s get back to the central question: who should be teaching yoga? The answer is the same as for any topic, whether mathematics, physics, astronomy, music or literature. A topic should be taught by those who have knowledge of it. Regardless of their age, gender or race, a teacher needs no more — and no less — than expertise of their subject. This gets more complicated because of the unequal power structures permeating the world. Those that know should teach. However, those that have resources should work to make sure that those who have less still have the opportunity to learn if they choose to. Perhaps the question is not who should teach, but rather how do we make high quality education affordable and available. This issue has quickly moved in the wrong direction as more and more "teacher" trainings see big money to be made. This is in exchange for the promise of the title of teacher, often with not enough regard for the task of actually training a teacher. As for the suggestion that non-Indians should not teach yoga, the nationalistic element should quickly be discarded. Furthermore, we need to address the quality of yoga teachers. The only worthwhile question to ask about a potential yoga teacher is this: do they know what they are doing? Read about the premodern version of Bow Posture, dhanurasana, here. For the past 100 years or so, Bow Posture is done lying on the belly, holding the feet or ankles, and bending the body backward, as pictured above in 1925. Prior to that, the posture seems to have been done sitting and pulling the feet toward the ears. The question remains: Where and when did the posture transition into its modern iteration?

These premodern prone backbends are not called Bow Posture. By 1925 when Yoga Mimamsa publishes instruction, the modern die for dhanurasana seems to be set.

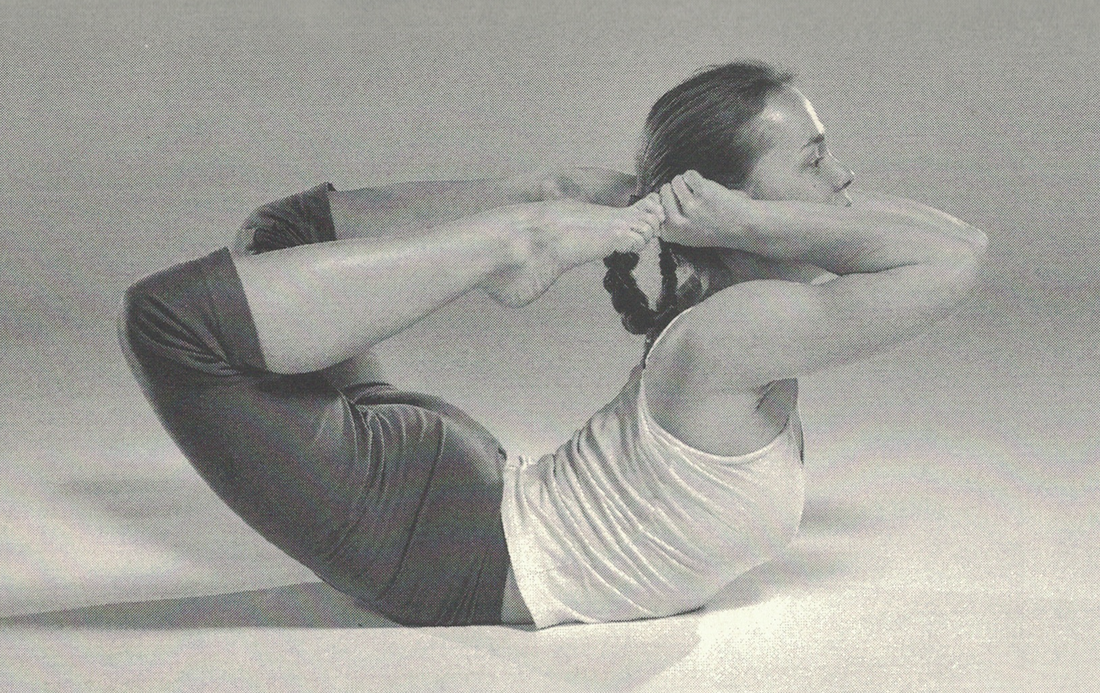

Kuvalayananda's book Popular Yoga Asanas from 1931 also includes Bow Posture, which is no surprise since it is drawn largely from issues of Yoga Mimamsa. Krishnamacharya's Yoga Makaranda in 1934 is curiously devoid of the posture. It makes one wonder about the influence of the Sritattvanidhi above.

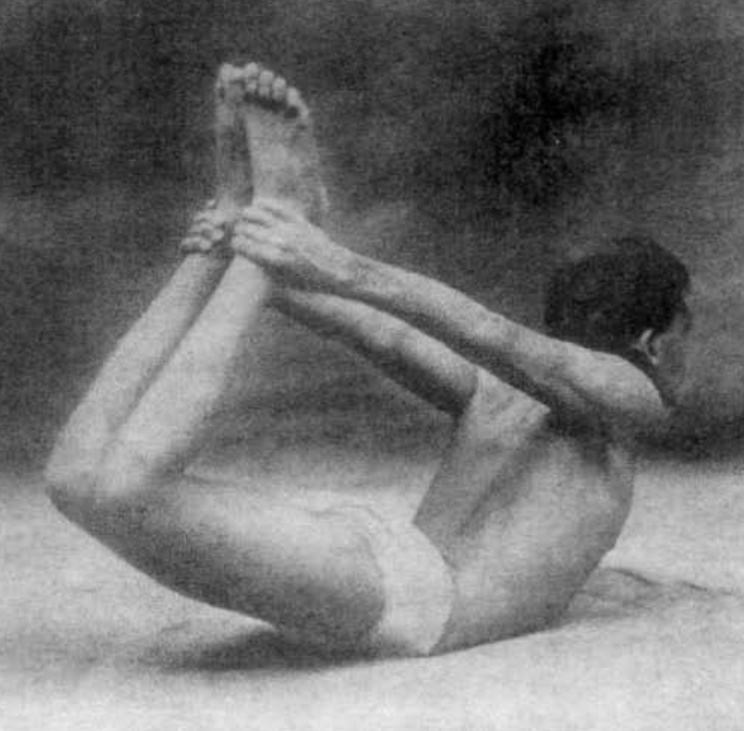

Nearly every modern text that we examined contains the posture, from North India's Shivananda lineage, East India's Ghosh lineage, South India's Krishnamacharya lineages, to Europe.

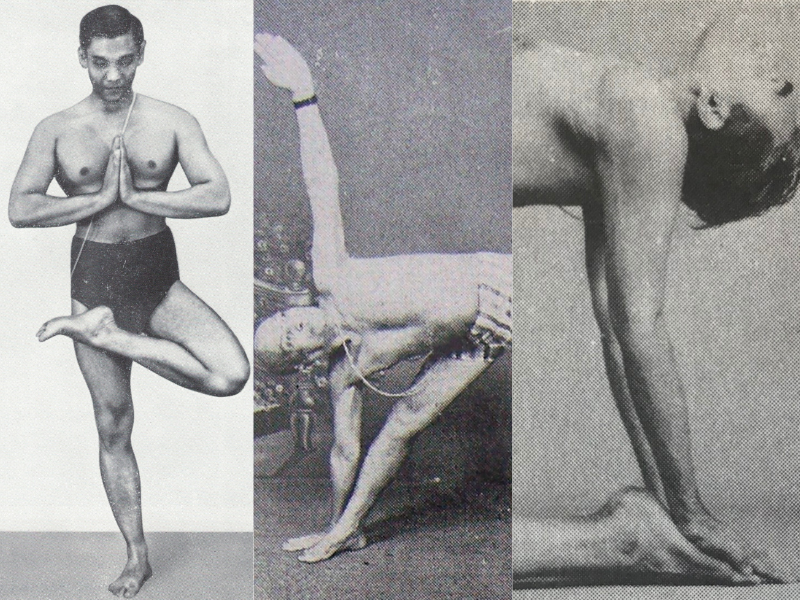

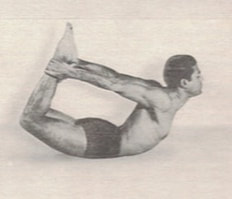

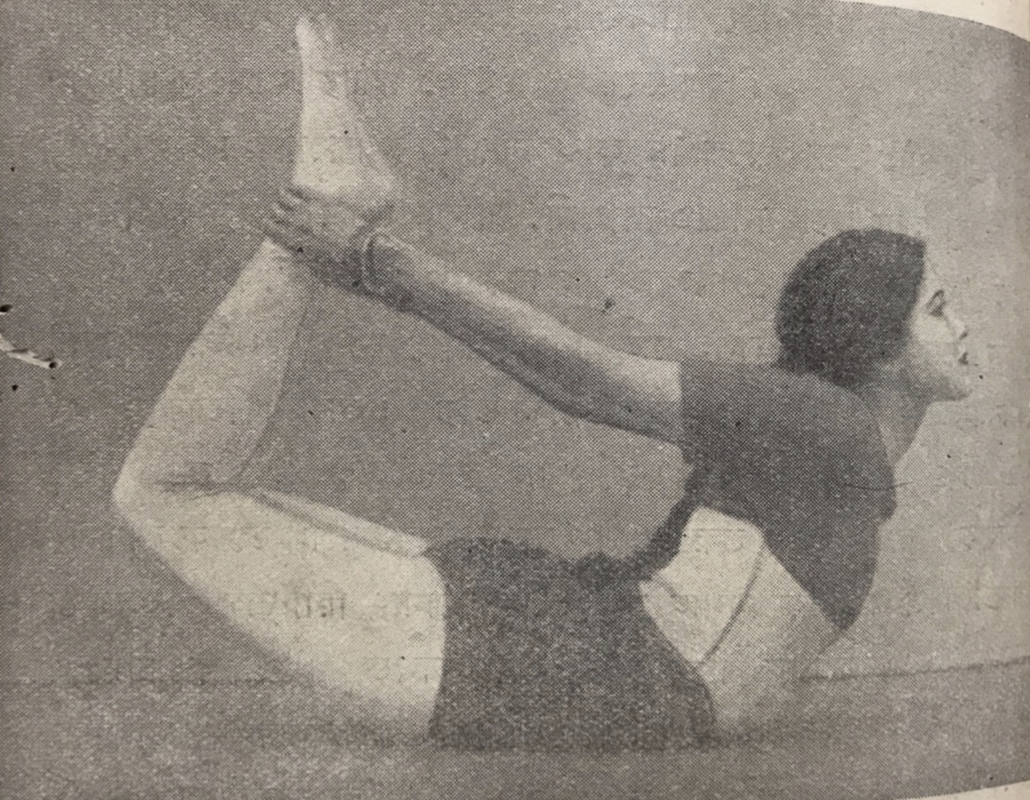

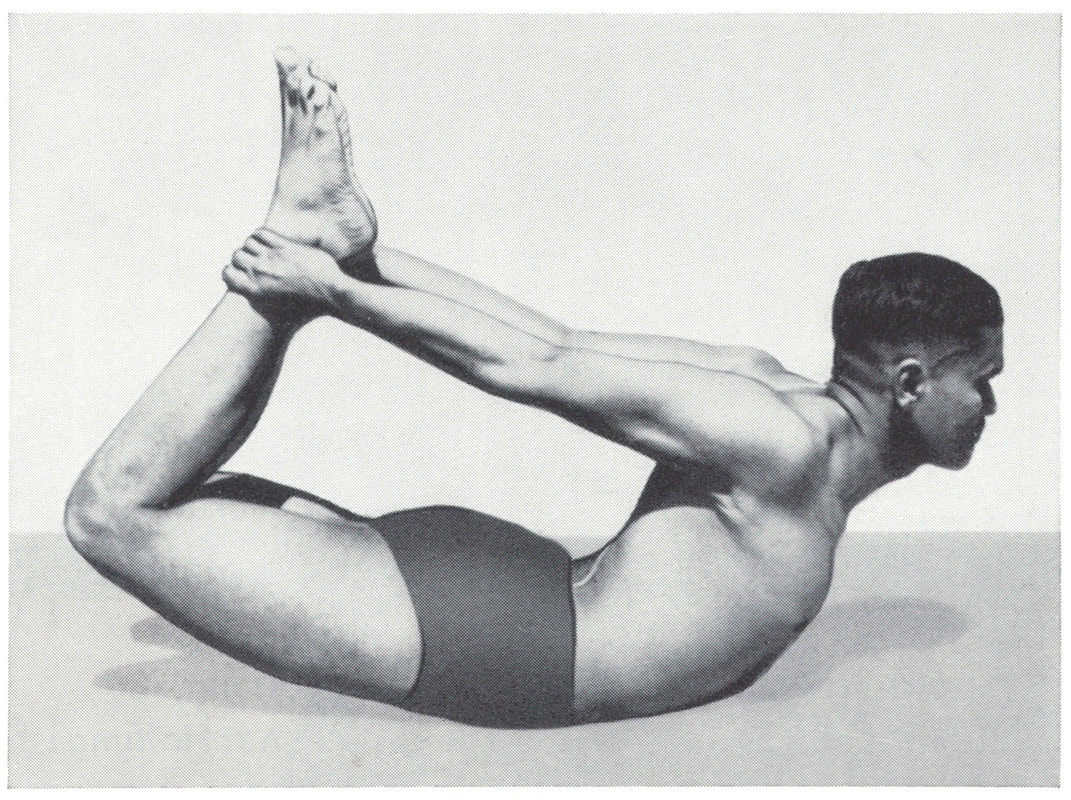

All the students of Bishnu Charan Ghosh include Bow Posture in their instructions. This includes Buddha Bose (above), Labanya Palit in 1955, Ghosh himself in 1961 (demonstrated by his daughter Karuna), Dr Gouri Mukerji in 1963, Monotosh Roy in the 60-70s, and Bikram Choudhury in the late 60s.

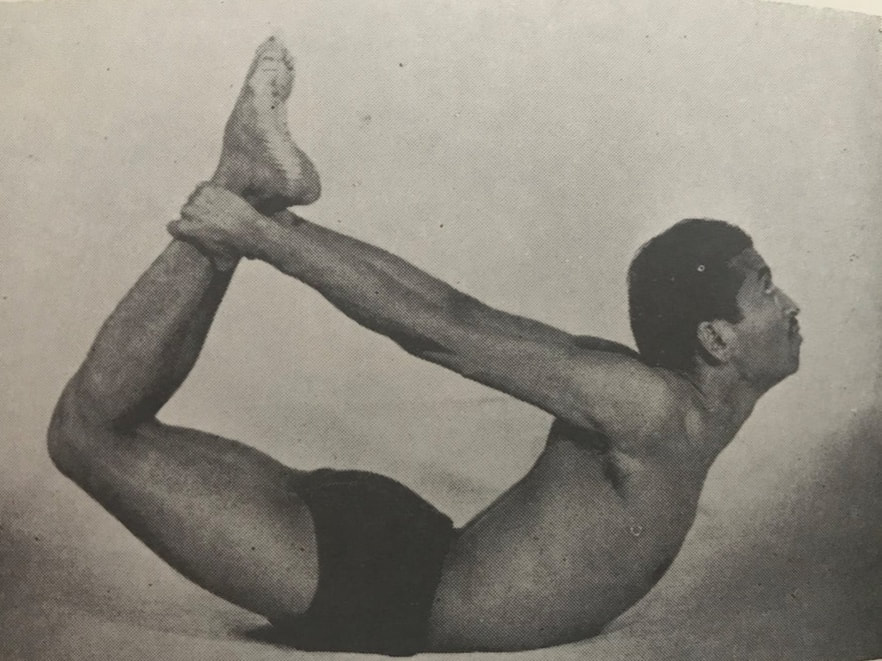

Iyengar, in his hugely influential Light On Yoga, is specific about where to carry the body's weight and also to keep the knees slightly apart: "Do not rest either the ribs or the pelvic bones on the floor. Only the abdomen bears the weight of the body on the floor. While raising the legs do not join them at the knees, for then the legs will not be lifted high enough." (Iyengar 1966: 101-2)

The instruction and performance of Bow Posture has been mostly consistent from about the 1920s. It is still unclear when it transitioned from the premodern, seated version into the prone backbend. Its hyper-modern shift to greater depth that resembles contortion more than dhanurasana is also interesting, but a topic for another time.

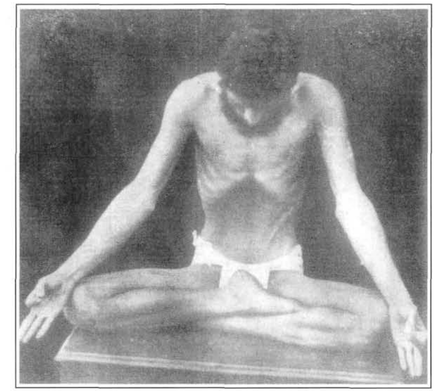

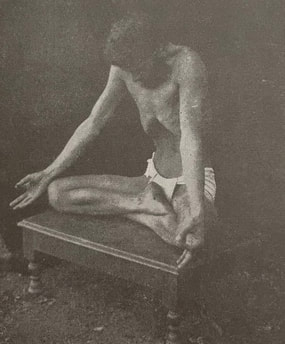

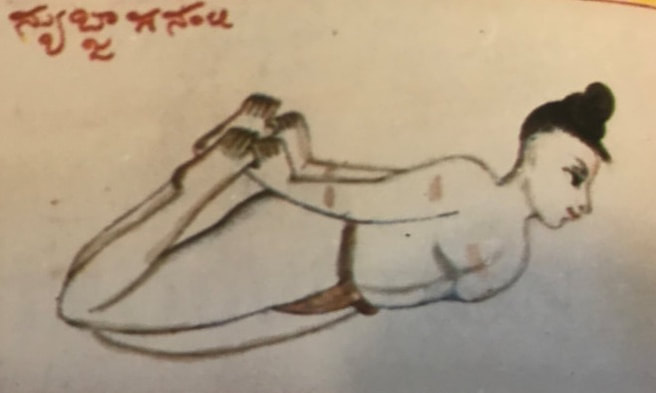

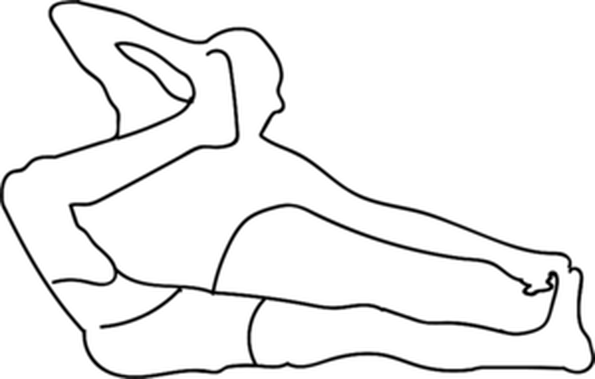

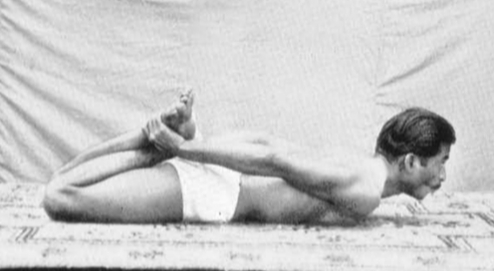

Bow Posture, dhanurasana, is one of the few postures of premodern Hathayoga that is not a seated, cross-legged, meditative position. Its first known instruction is from the 15th century in the Hathapradipika, and it is also included in the 17th century Hatharatnavali and the 18th century Gheranda Samhita. Interestingly, these premodern versions of Bow Posture may be different from the modern understanding. The modern version of Bow Posture, which has been prominent for the past 100 years or so, is done lying on the belly, holding the feet or ankles, and bending the body backward. Prior to that, the posture seems to have been done sitting and pulling the feet toward the ears. Bow Posture's earliest known instruction is in the 15th century Hathapradipika: "Bring the toes as far as the ears with both hands as if drawing a bow. This is Dhanurasana" (HP 1.25). (1) The Hatharatnavali from the 17th century repeats the Sanskrit instructions word for word. Here is a different English translation: "The big toes are held with the hands and are pulled up to the ears (alternately). Thus, one assumes the shape of a stretched bow. This is dhanurasana" (HR 3.51). (2) This posture is done sitting and pulling one foot to the ear as the other leg stays straight, making the body look like a drawn bow. There are two ways that the instruction has been interpreted, depending on whether the hand grabs the foot on the same side of the body or opposite. So this posture has been interpreted as pictured at the top, with the hand pulling the same side foot toward the ear; or with the leg crossing the body as pictured directly above. The instruction is not specific, making it likely that crossing the body is not intended. Nowadays, these positions are still taught sometimes. They are often called akarna dhanurasana, which means Bow to the Ear Posture; or akarshana dhanurasana, which means Bow Pulling Posture.

Bow Posture is also in another well-known premodern text, the Gheranda Samhita, from the 18th century. The instruction has changed a little from the Hathapradipika and Hatharatnavali: "Stretch the legs out on the ground like a stick, extend the arms, hold both feet from behind with the hands, and make the body curved like a bow. That is called Dhanurasana" (GS 2.18). (3) The interesting new instruction here is that the feet are held "from behind". Some interpret this as bending the legs backward and holding the feet, as one does in the modern backbend. But it is entirely possible that this is the same posture as instructed earlier, and the cue to hold the feet from behind is not particularly ground-breaking. The first words in this instruction, to "stretch the legs out on the ground like a stick", are identical to the instructions for Stretching Posture, paschimottanasana. This is perhaps a clue that the Bow Posture in the Gheranda Samhita is intended to be done sitting down with the legs stretched forward.

It seems most likely that the premodern Bow Posture was intended to be seated, pulling the toes toward the ears. The questions arise: When and why did it shift to the modern understanding of a prone backbend? As we will explore next, it seems to be established as the 'modern' Bow Posture by the 1920s.

(1) Akers, Brian Dana, trans., 2002 Hatha Yoga Pradipika NY: YogaVidya.com (2) Gharote, M.L., Devnath and Jha, editors, 2014 Hatharatnavali Lonavla Yoga Institute: Pune [2002] (3) Mallinson, James, trans., 2004 Gheranda Samhita NY: YogaVidya.com While those based in the West may not immediately know his name, Dr Dibyasundar Das is a significant figure in the yoga lineage of Bishnu Charan Ghosh. He died Wednesday morning at the age of 68.

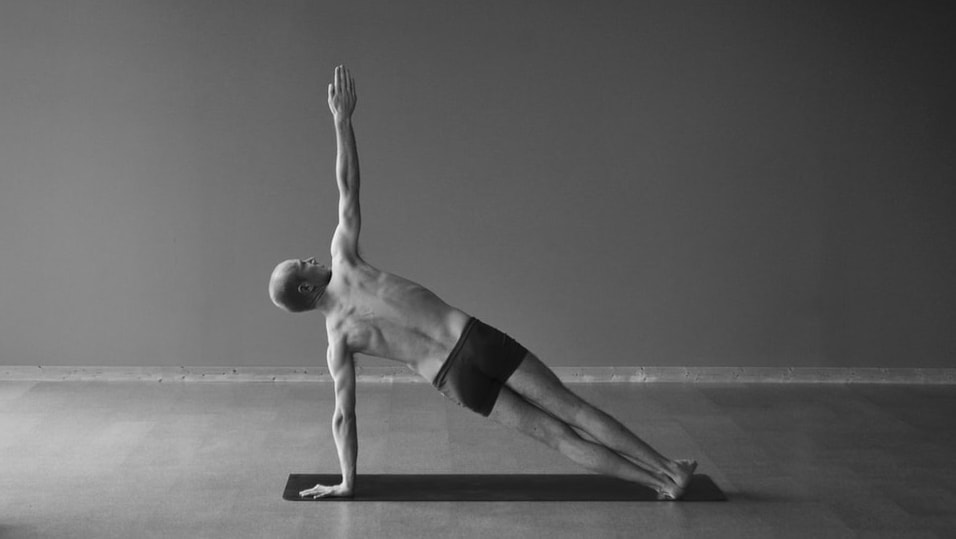

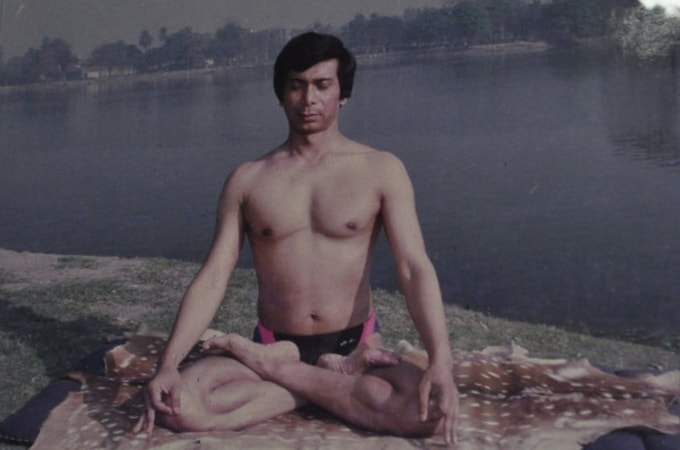

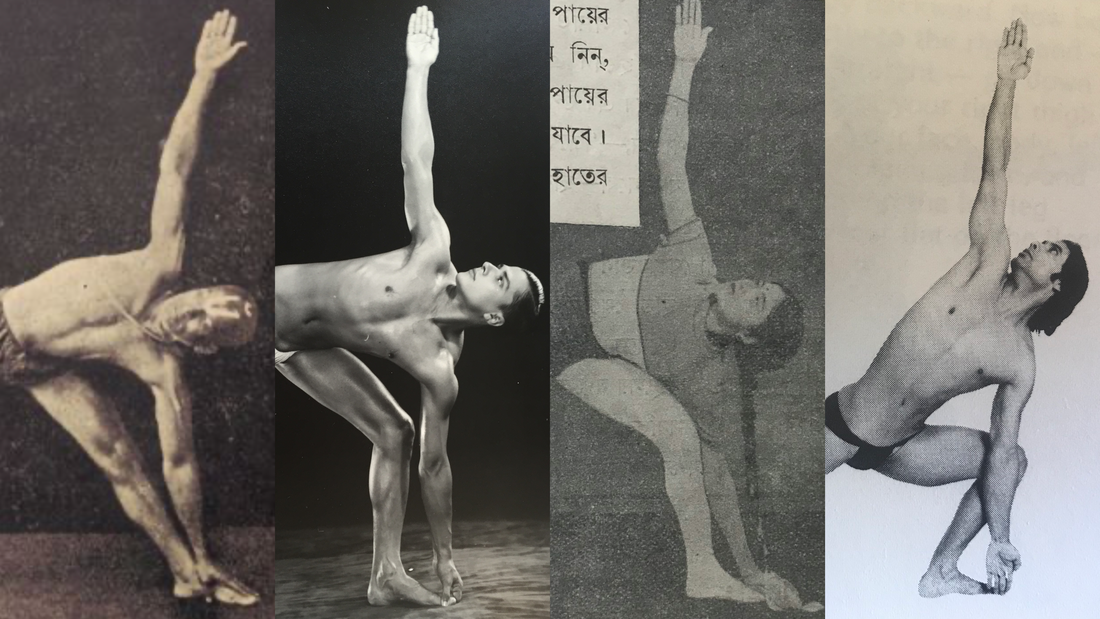

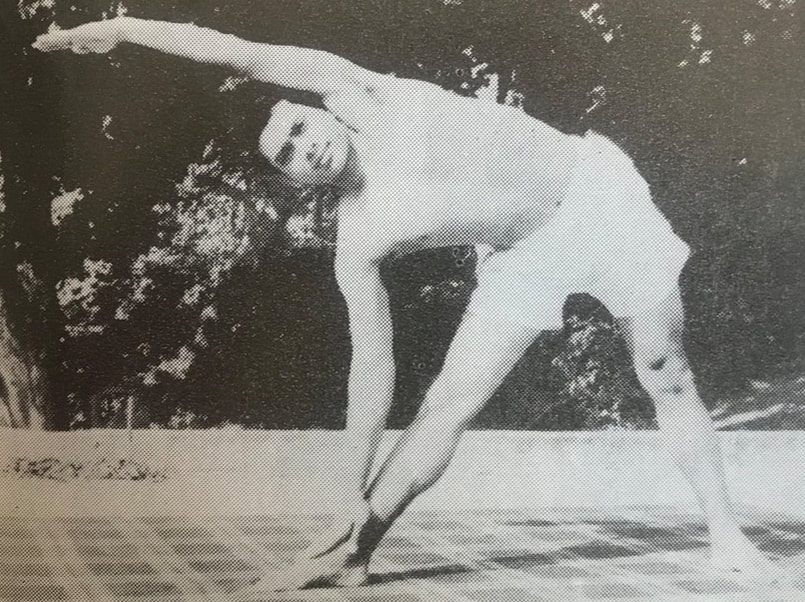

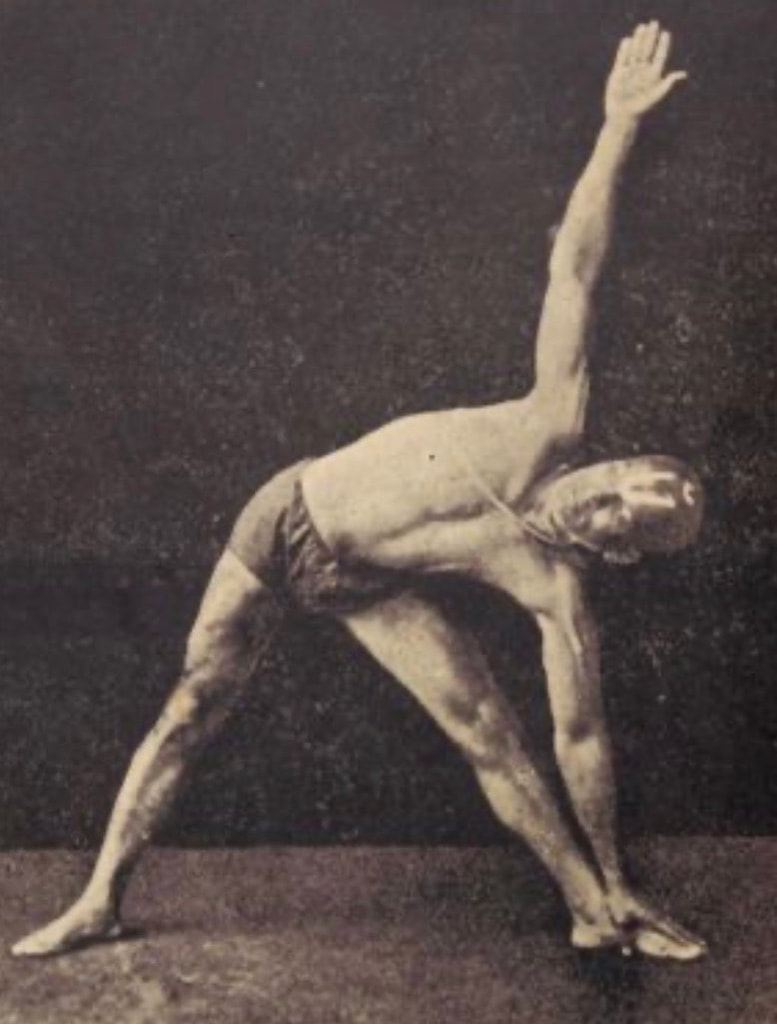

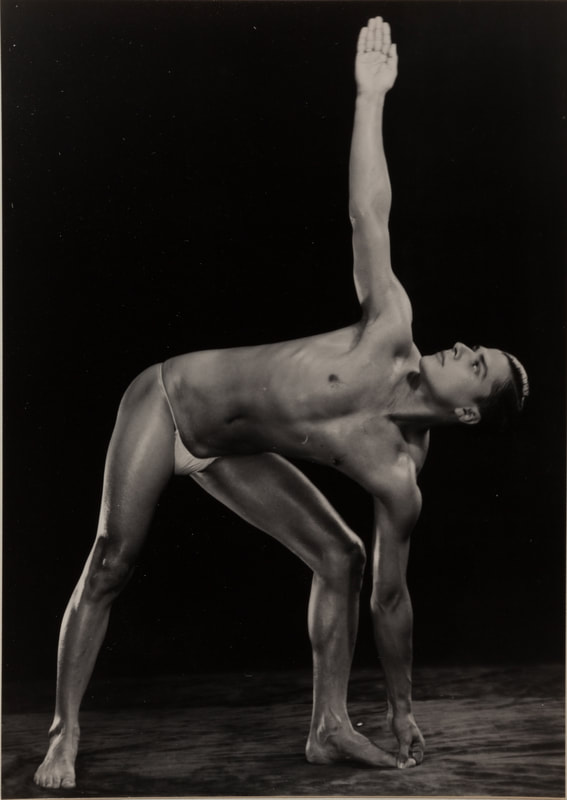

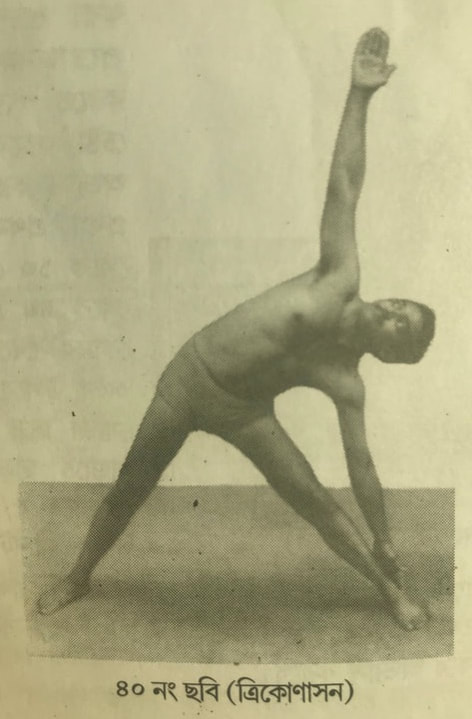

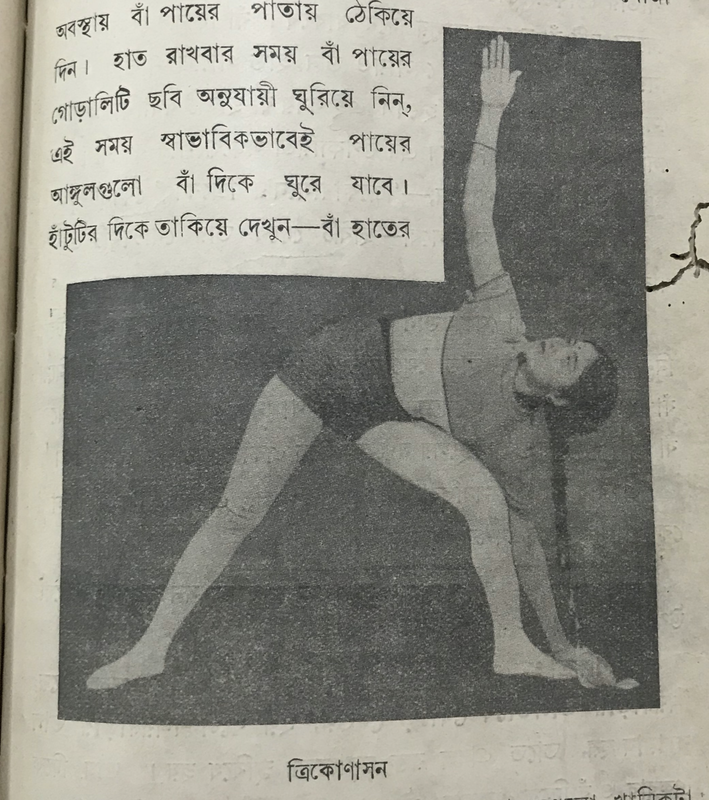

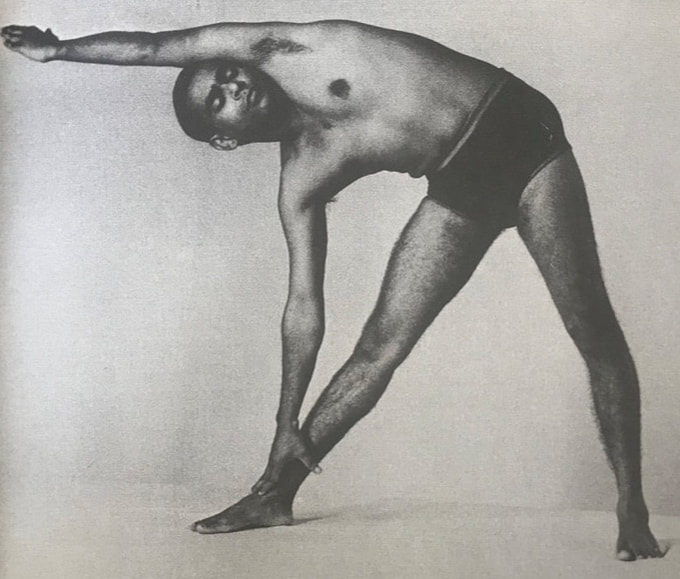

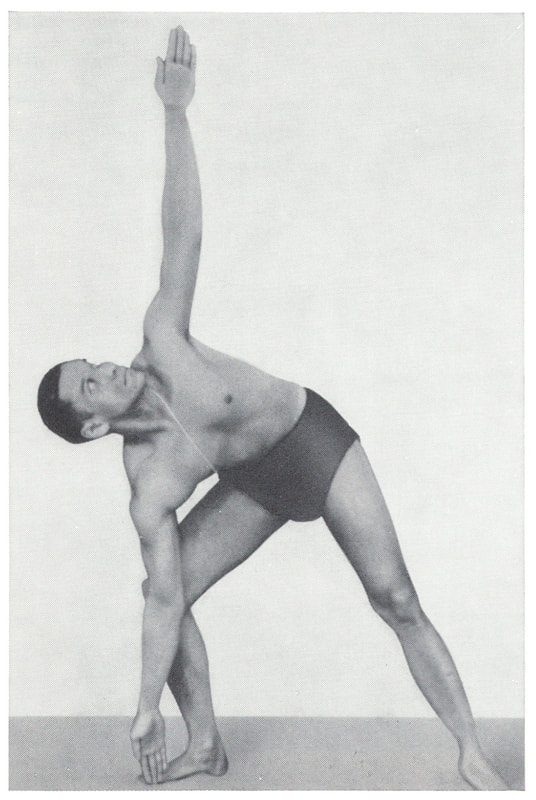

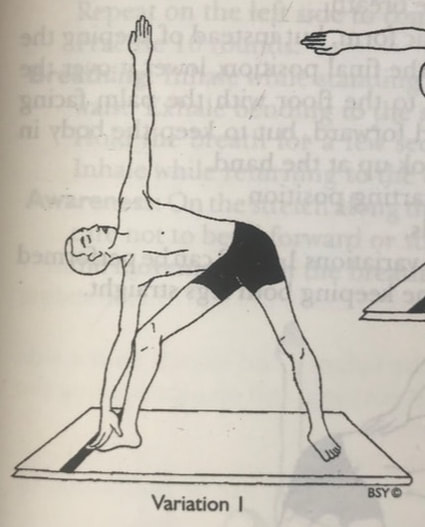

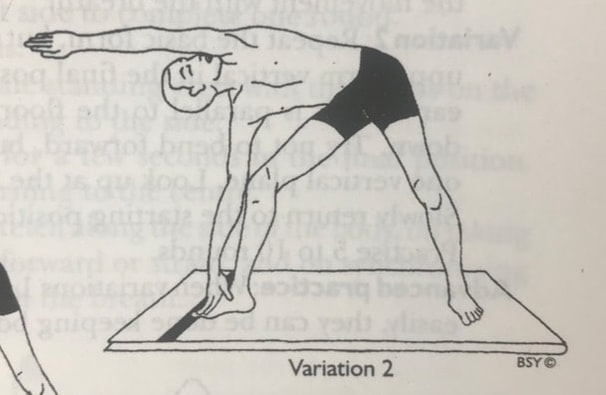

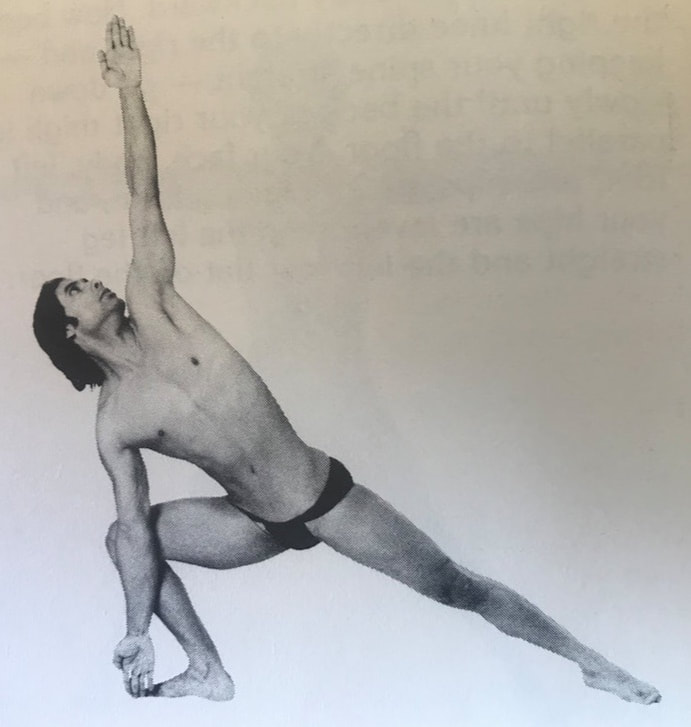

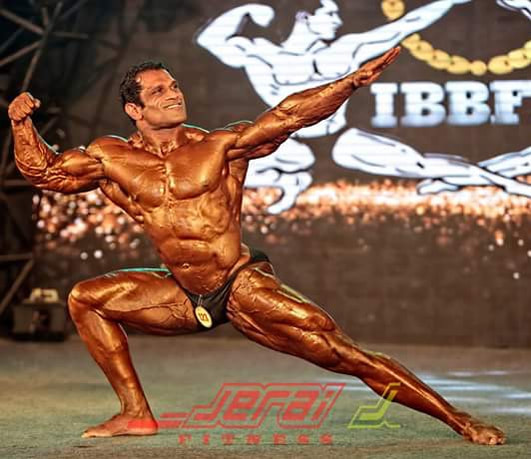

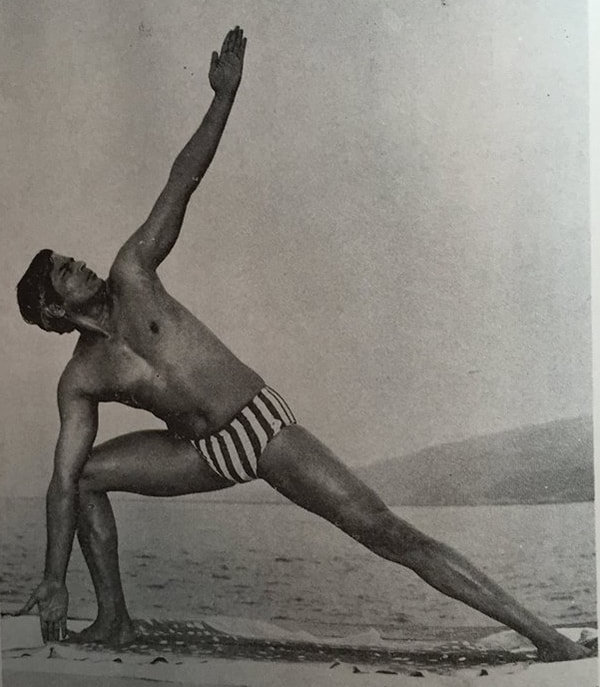

His family looms large in the yoga of Kolkata, including his sister, Kushala, and his brother, Premsundar. (Dr Premsundar Das is best known in the West.) Dr Das devoted his life and work to serving and bringing relief to many through therapeutic yoga and homeopathic medicine. He was trained by none other than Bishnu Charan Ghosh, as well as Dr. Gouri Shankar Mukerji and Sananda Lal Ghosh. In 1986 he founded the World Yoga Society to greater serve individuals as well as train others through courses in Yoga Therapy. Its youtube channel is extensive. Today his photos line the walls at Ghosh’s College displaying how important he is to this tradition of yoga. Further testament to his skill and achievements live on in the many lives of those who he helped. Our best wishes go out to his family and loved ones. Triangle Posture - Trikonasana - is a relatively new addition to the physical practices of yoga. Along with most other standing postures, Triangle is absent from the texts of Hathayoga. It makes an appearance in the 1920-30s as yoga in India is becoming more exercise oriented. This makes it strange to speak of something like a 'traditional' Triangle Posture, since its use in yoga has yet to hit the hundred-year mark. Below we have traced the transmission and progression of Triangle Posture through the last century, especially in Kolkata and the Ghosh Lineage. Among the students of Ghosh, it was consistently practiced for decades since its earliest iteration in 1938 with Buddha Bose. In the 1960s the posture disappears before being reborn as a deep sideways lunge. This is seen in Bikram Choudhury and Jibananda Ghosh but nowhere in Kolkata itself. It seems that this is an influence from bodybuilding, though it is unclear exactly when, where and why the change occurred.

It would appear that the evolution of Triangle Posture into a deep sideways lunge shows influence from bodybuilding. It is unclear if this is an innovation of Choudhury himself, or if it occurred more generally around the time when he was learning. Evidence of bodybuilding's influence on Choudhury's instruction is visible in other places as well, including the instruction to 'lock the knee'.

Triangle Posture itself is a relatively new addition to 'yoga' practice, probably being adopted in the 1920-30s along with other standing, exercise-based positions and movements. After its adoption as a yogic asana, it was relatively stable in its practice for decades. In the Ghosh lineage, it was done with one knee slightly bent, the torso parallel to the ground, and one hand touching the foot. In the 1970s, the posture underwent a significant change, perhaps being reinvented entirely, turning into a deep sideways lunge that resembles a bodybuilder's pose. This version is taught by Choudhury and his students.

For another posture that underwent significant development and change in the 1960-70s, see the Standing Bow Posture. (Thanks to Jerome Armstrong for the insight about bodybuilders.) |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed