|

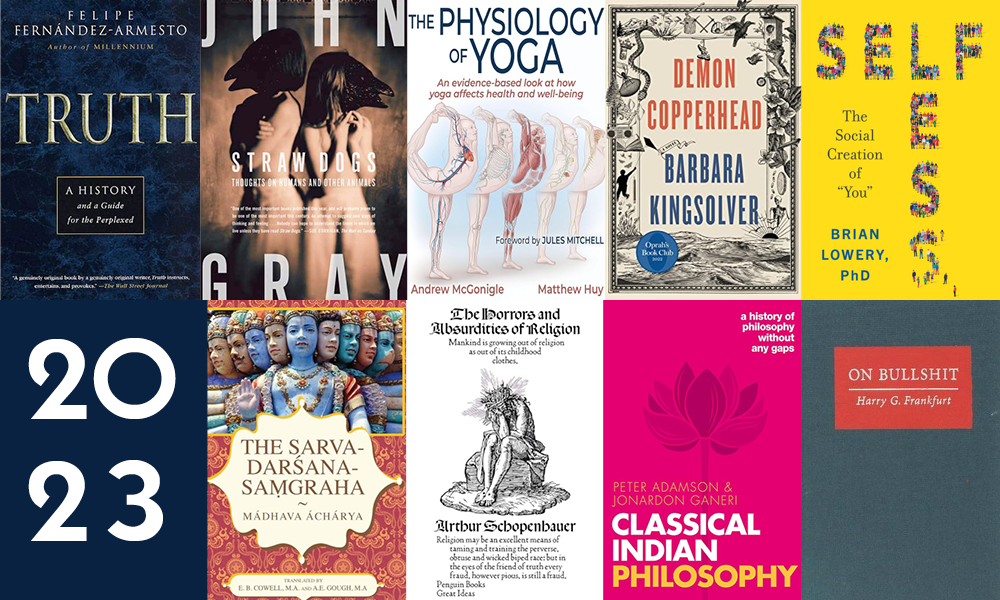

I absolutely love to read. A book is a window into another time and place, another person's mind, another way of seeing and thinking. Books teach me what it can mean to be human, but also what it might be like to be a robot or a microbe. Looking back, for me this was a year about truth, or rather the idea of truth: What I think is right, what I want to think is right, where that view comes from and why it may be flawed. Books that made it onto the list include ones about bullshit, the history of truth, the human obsession with our own meaning, and how our identity changes depending on the situation. Here are nine books I read this year that changed the way I think. On Bullshit by Harry G. Frankfurt Let's start with this little philosophical essay. The title is funny, and it seems like this book is going to be a gag, some clever insights about what it is to talk 'bullshit.' But this essay is something else entirely: A serious philosophical inquiry into the nature of bullshit. What is it? How does it differ from lying or ignorance or nonsense? Frankfurt concludes that a bullshiter simply has no regard for the truth. He does not care if he is right, wrong, true or false. He is only interested in getting a desired reaction at that moment. Bullshit "is grounded neither in a belief that it is true nor, as a lie must be, in a belief that it is not true. It is just this lack of connection to a concern with truth — this indifference to how things really are" that is the essence of bullshit. This revelation is shocking: a liar has regard for the truth. He just decides to state something that he knows is untrue, called a lie. But a bullshitter doesn't relate his statements to the truth at all. Classical Indian Philosophy by Peter Adamson & Jonardon Ganeri I am always on the lookout for clear explanations of history and philosophy, two topics which are infinitely complex and can easily devolve into self-referential terminology and nonsense. So I was pleasantly surprised to find this volume about Classical Indian Philosophy which is a well-balanced combination of deep and accessible. It begins with the Veda and Upanishads, effortlessly explaining the salient overarching points of these vast and layered eras. It glides through the big philosophical movements in Indian thought, including theism, non-violence, yoga and Buddhism. My favorite part of the book was the middle section, which digs into the philosophical developments of the middle-era Buddhists and Jains. These groups were highly philosophical, and I haven't seen such a lucid overview in any other volume. For example, there is a short chapter explaining Nagarjuna's "Tetralemma", a four-pronged logical negation that is usually off-putting in its detail. The explanation here is illuminating, including this passage about the dual possibilities of the phrase, "Don't slaughter a goat." It "might mean that you should slaughter a non-goat. Here the noun ('goat') is negated: you should indeed slaughter something, perhaps a cow or chicken, just not a goat. Or the verb ('slaughter') might be negated: the instruction would tell you to refrain from any sacrificial act at all." This book's short chapters and vast overarching scope make it a good reference to dive into according to your interest. Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver This novel needs no promotion since it has won prestigious awards and been a bestseller. I finally picked it up, and the first sentence assured me that I was in the hands of a master. The story is of a boy in Appalachia, his exploits and struggles. The basis of the story owes a lot to David Copperfield, but the first person voice of the narrative is gripping from the first word to the last. The Horrors and Absurdities of Religion by Arthur Schopenhauer This year I have often come across the work of Schopenhauer, a European philosopher who was greatly influenced by the Upanishads and Buddhism, and in turn affected modern yogis like Yogananda. So when I stumbled across this little book in a bookstore I had to read it. The title is certainly provocative, but he won me over pretty quickly on the first page with this statement: “What I respect is truth, therefore I can’t respect what opposes truth. Just as the jurist’s motto is…Let Justice be done though the world perish, so my motto is…Let truth prosper though the world perish.” What follows is a strong critique of religion which bears all the hallmarks of 19th century enlightenment thought and orientalism. Some of his arguments require a grain of salt, but what philosopher doesn’t? Schopenhauer does put his finger on one element with remarkable clarity: man’s need for greater meaning, what he calls the ‘metaphysical need.’ “Man is an animal metaphysicum, that is, his metaphysical need is more urgent than any other; he thus conceives life above all according to its metaphysical meaning and wants to see everything in light of that.” All in all, a challenging and thought provoking read. The Physiology of Yoga by Andrew McGonigle and Matthew Huy Most of the time I am torn between the opinion that there are more than enough books about yoga anatomy — perhaps too many — and the opposite view that we could really use some new ones with clear sources and explanations. This book, which is new this year, is a brilliant addition to the field. What makes this book special is its combination of citing scientific evidence and awareness of traditions and rumors in the yoga world. My favorite parts of this volume are the "Myth or Fact" inserts that address common beliefs among yoga teachers and students: that Headstand brings more blood to the brain; that Shoulderstand stimulates the thyroid gland; that twists detoxify the organs. The authors discuss any studies that have been done on the topic and what conclusions we can draw. Often there are no studies, so we are left to rely upon our other knowledge of anatomical and physiological function. McGonigle and Huy excel here, where they illuminate the amount of speculation as well as point us to more probable scientific explanations. Truth by Felipe Fernandez-Armesto A book about the history of truth?! This must have been written just for me! There are few things I love more than history and explorations of complex ideas. But this book is not exactly what I expected. I imagined a sort of explanation of how truth came to be so important and how it developed its signature qualities. But this is much, much more, digging into different conceptions of truth through time and culture. Fernandez-Armesto breaks the types of truth into four groups. Who would have thought there may be four kinds of truth?! Throughout the volume, I came to realize that the conception of truth itself is not terribly specific; that it depends on what we think it is. I suppose that shouldn't be surprising — I went into the book with one simple idea and came out with a far more complex view. The Sarva Darsana Samgraha by Madhava Acharya This volume is more specific to my interest in the history of yoga and philosophy. The best-known system of Indian philosophical systems has 6 members, the six orthodox darshanas. But there are many other ways of thinking, and even well-developed and influential systems that are not included on this list. This book, the Sarva-Darsana-Samgraha or Compendium of All the Systems, lists and explains 16 different spiritual-philosophical viewpoints. It contains all the familiar orthodox systems, like Samkhya and Yoga. But it also includes Buddhism, Jainism and strict materialism, among many others. Each chapter digs into some granular details of perception, knowledge and being. This is a book for those rare individuals who are interested in the somewhat arcane study of Indian philosophical history, as well as those who can tolerate minute philosophical debate and old uses of language. A difficult book to read and comprehend, but an eye-opener one for me this year. Selfless by Brian Lowery I stumbled across this book while wandering through a bookstore. Its title is compelling and in direct conversation with Vedantic and yogic concepts of an eternal, unchanging Self. The thesis here is that we have no single self, that our identity is constructed according to our surroundings: "Your self is constructed and reconstructed in a swirl of ever-evolving relationships." These relationships include family, work, politics, nation, and an infinite number of variations. There is a reason that I act differently around a three year old than a 50 year old; I act differently around my significant other than my boss. Selfless argues that we are actually a different person in each situation, because part of what defines us is who we are around, and what we are trying to accomplish. This book also explores the ideas of history, tradition and community. Often we adopt certain "selves" to create connection and continuity to the past or groups of people we admire. For me, it shone a lot of light on why we defend our identities and communities when they are destabilized. This book was one of my favorites of the year. Straw Dogs by John Gray

This was my favorite book of the year, and one of the best books I've ever read. It combines mind-blowing ideas with a sharp reading of history, religion and science, and it is incredibly readable. The pages fly by. On nearly every page I was gobsmacked by some revelation, some shocking idea that was as bold as it was clear. There is the idea that 'truth' is not something that serves humanity's evolution; there is no evolutionary advantage to knowing the truth. (This is of course interesting to compare to the book Truth above, and clearly something that was on my mind this year.) Gray writes, "Modern humanism is the faith that through science humankind can know the truth — and so be free. But if Darwin's theory of natural selection is true this is impossible. The human mind serves evolutionary success, not truth. To think otherwise is to resurrect the pre-Darwinian error that humans are different from other animals." Here you see the way that Gray's book dismantles ideas of scientific humanism, even arguing that the science and logic we revere only serves to undermine our vision of ourselves as a special, chosen species. The volume is full of challenging ideas like this, unafraid of poking holes in even the most sacred of concepts. I admire its clear-eyed audacity, like the boy who shouts that "the emperor has no clothes!"

0 Comments

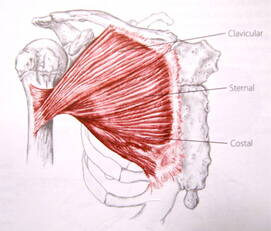

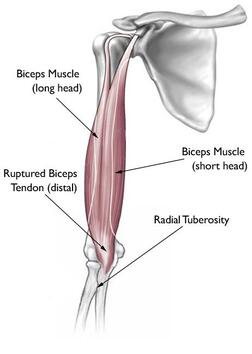

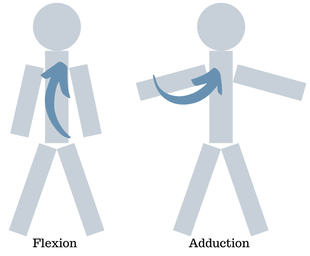

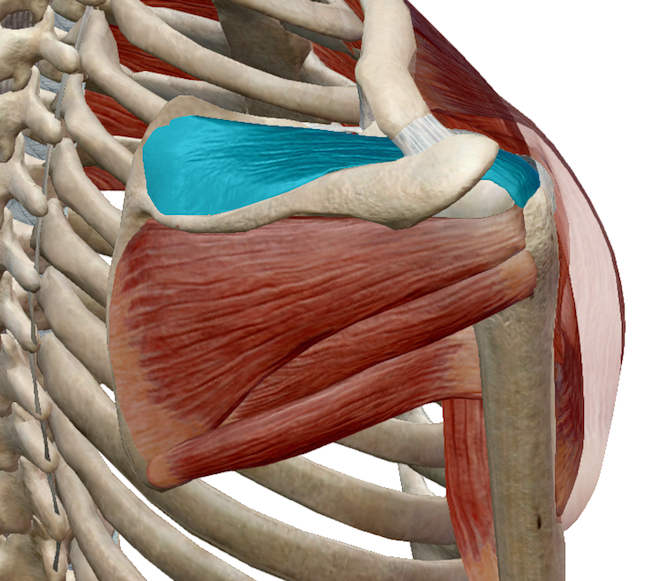

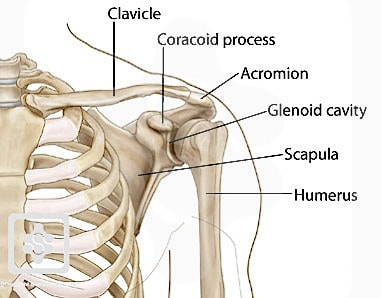

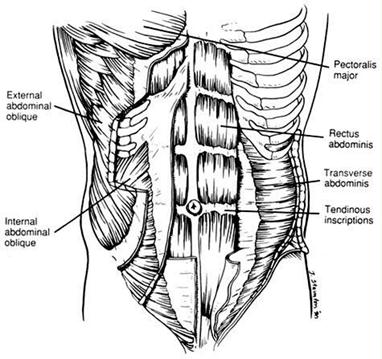

This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. Last month we wrote about the common shoulder injury Shoulder Impingement. The other common injury to the shoulder happens in the front, where the short head of the biceps muscle attaches to the shoulder blade, a biceps tendon strain. This injury is most common in Ashtanga Vinyasa and subsequent 'flowing' yoga styles that incorporate a lot of Sun Salutations and chaturangas. The shoulder can't do this action very well, and the biceps become strained before too long.  Pectoralis major ("pec") Pectoralis major ("pec") To understand this injury, we have to talk about shoulder mechanics and the muscles that move the arm. PECTORALIS MAJOR & ADDUCTION One of the biggest and most powerful muscles of the shoulder is the pectoralis major, commonly known as the 'pecs' or just the 'chest muscle', pictured to the left. It connects the arm (humerus) directly to the middle of the chest. Its main function is to pull the arm toward the chest in an action called adduction. Try it: hold your arm out to the side (as pictured below, labeled adduction), then bring your arm toward the center, so you end up with your arm pointing forward. As you do this, you will feel your 'pec' engage. When you apply this motion to something like a pushup, the arms need to be away from the body, so the pushup motion will be pulling the arm inward toward the chest. Simply put, this means keeping your elbows away from the body. This is the safest way to do any pushup motion.  BICEPS & FLEXION In contrast, if we start with our arms down by the sides and lift them up until they point forward, this is called flexion (pictured above, labeled flexion). When we lift the arm like this, the pec doesn't get activated much, so the work is done by much smaller muscles like the anterior deltoid (the front of the shoulder cap) and the biceps. The biceps cross two joints; they bend the elbow and also flex the shoulder. But they don't have the power to move the body's entire weight. When we do pushups or chaturangas with the elbows close to the sides of the body, we are essentially moving the shoulder in flexion. This is not a powerful nor particularly healthy way to move so much weight. When we do this repeatedly, the bicep tendon (usually the short head at the attachment with the coracoid process of the shoulder blade) will often be damaged. This manifests as pain or soreness in the front of the shoulder. There is a common belief that keeping the elbows close to the body uses the triceps more than if the elbows were wider. This is not true for the simple reason that the triceps straighten the elbow, and the elbow is doing a similar action in both versions. The big impact is on the shoulder and what muscle group you use when doing a pushup or chaturanga motion. IN CONCLUSION There is nothing inherently wrong with keeping the elbows close to the body and flexing the shoulder. The problems arise when we do this with our entire body weight and do it repetitively. This is how injury usually happens. Consider making the elbows wider, which will strengthen the huge pectoralis major muscle as well as be safer for the smaller muscles of the shoulder. Happy, healthy practicing! This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. Two common injuries in yoga happen in the shoulder. One is in the front of the shoulder---the biceps tendon---which we will address next time. The other is in the top of the shoulder, called impingement. It happens when the arm lifts up high; the arm bone can bump against the edge of the shoulder blade, called the acromion, and damage the tendon there.

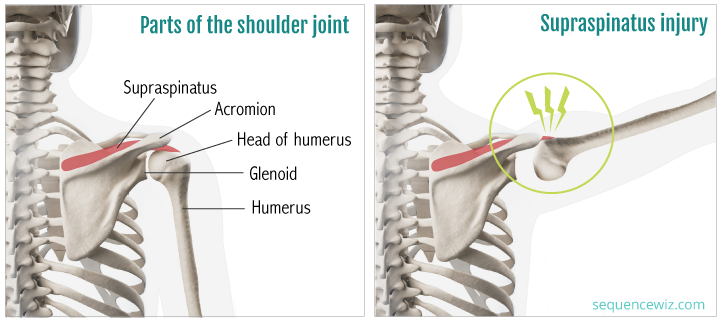

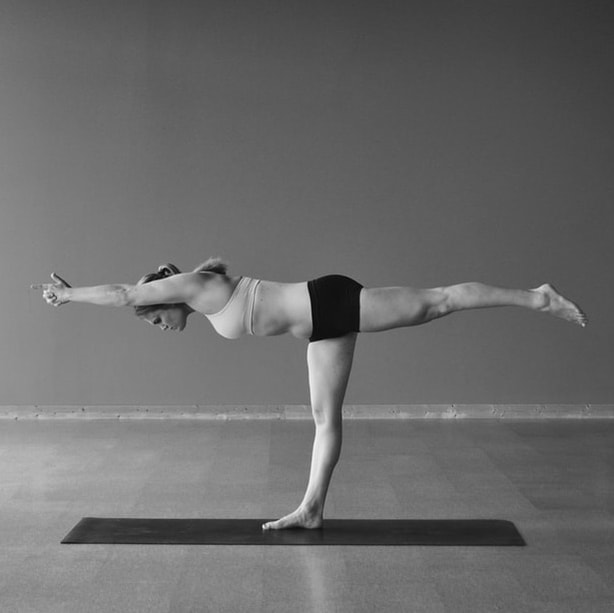

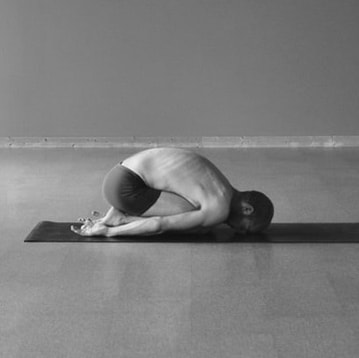

HOW THIS CAN HAPPEN In yoga, this happens most often when we force the arms overhead. Think of any time you link your hands together and then try to straighten your arms using force. As pictured below, it happens in Half Moon Backbend, Half Moon Sidebend, Balancing Stick and Half Tortoise, among others. (It also happens in Downward Facing Dog.) When we force our arms to straighten overhead, we usually use the triceps, a muscle mainly of the elbow, to compel movement in the shoulder. This is where we get into trouble and impingement can happen. You will feel a 'pinching' sensation in the top and outside of your shoulder. This is the bones bumping into each other, damaging the soft tissue. If the shoulders become injured this way, they will be painful whenever lifting the arms sideways, and the breathing exercise pictured at the top will cause pain.  HOW TO HELP The simplest and most effective way to avoid this injury is to not link your hands together. Just place them side by side without interlacing the fingers. Interlacing the fingers and forcing the arms straight overhead is the easiest way to create the injury. Or don't lift your arms overhead (pictured below left). Most postures can be done quite effectively without the arms overhead. All of the positions pictured above don't require the arms to get the primary benefit. Alternatively, you can lift your arms forward and up (pictured below) instead of out to the side. This will help the shoulder blades move into the proper position and keep the shoulders healthy. In the breathing exercise, pictured at the top, you can keep your elbows lower, not lifting them higher than the shoulders. This will prevent further irritation of this area. To build strength in the area, postures like Full Locust will help (pictured below right). By pulling the shoulders back and together, we build strength in the back of the shoulder to help stabilize and balance the joint. CONCLUSION

The moral of the story is that we should be aware and careful when lifting the arms overhead, especially if we are gripping the hands together and straightening with force. If there is a 'pinching' sensation in the top of the shoulder, back off immediately. There is nothing there to 'stretch', and it is likely that we are impinging our supraspinatus tendon. Try adjusting your approach to the posture and using your shoulders a little differently. Happy, healthy practicing. It can be difficult to know what is real in this world. The methods of yoga, spirituality and science have developed to explore this question. Sometimes they come to the same answers, but sometimes they contradict.

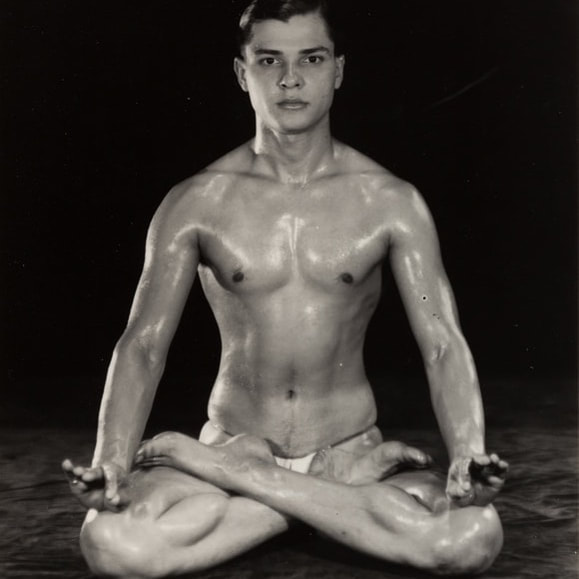

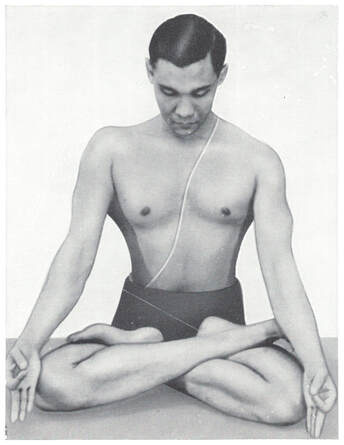

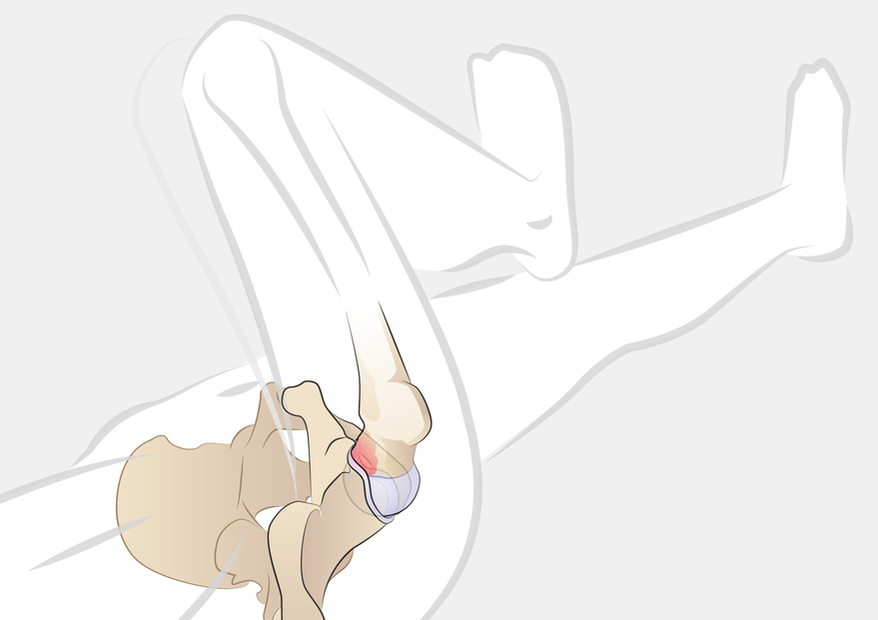

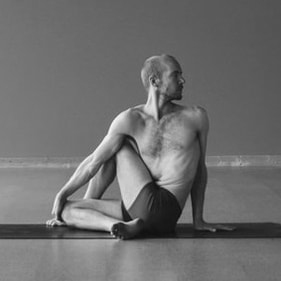

As yoga teachers, we are often confronted with the problems of: 'Why do we do these things?' and 'What is right?' We usually look in three places to find answers: tradition, science and personal experience. TRADITION We at Ghosh Yoga are fascinated with tradition, and we have researched it, studied it, lectured on it and challenged it. We have written about the relationship of oldness and tradition, the Spirit of Tradition, and the sometimes misleading value of tradition. With regards to these questions---what is real? and what is worth learning?---tradition plays an important role in yoga. Many of us are drawn to yoga because of its ancientness, sacredness and gravity. And the idea of lineage, teaching in the same way as you were taught, is a time-worn Indian method that has come to the West with yoga. At its best, a lineage links modern students with ancient teachers and sages. We must take these things seriously. What did our teachers think and what did they teach?If we look in older texts, what was being taught hundreds or thousands of years ago? Most importantly, how do these apply to modernity? Can we extrapolate our own situations, thoughts and perspectives from ancient teachings? SCIENCE In the past few centuries, scientific methods have developed that are centered around the reliability and repeatability outcomes. The sciences have improved our understanding of anatomy, physiology, biomechanics and neurology among other things. We can apply this knowledge to the body and mind in yoga practice. But it can sometimes come into conflict with traditional understanding. For example, humans did not know the intricacies of bodily anatomy until the 15th century CE. This is clearly depicted in art from earlier, where the body is only really understood by looking from the outside. Take this one step further inward, to the functioning of breathing, energy or the nervous system. These things have come into focus even more recently in human history. Therefore, when we look to 'tradition' for physical, anatomical or physiological methods, we must take great care. How does the ancient understanding line up with modern understanding? If there is a discrepancy, is it clear where, why or when that may have occurred? And which do we trust? (For the past few decades, increasing numbers of scientific studies are being done on the practices of yoga. Check out Pure Action.) PERSONAL EXPERIENCE It may seem obvious to say, but all of these practices and traditions of yoga are intended to be put to use by actual living humans, like us. They only come to life when they are studied and executed. Those experiences we have and the inner knowledge we gain are hugely valuable, and one might argue that they are the central purpose of it all. On the other hand, the root of all the spiritual traditions is that our ordinary knowledge and perception are lacking and misleading. We must look deeper and strive to understand what is difficult and hidden. So, partly, our experience is the most important element, but it can also be the most misleading if we are not careful. TAKING THE THREE TOGETHER When assessing the methods and goals of yoga, we constantly weigh the contributions of these three elements: tradition, science and personal experience. There are some instances when all three align. This is the case with Alternate Nostril breathing, a practice described in the ancient texts, explained clearly with the modern scientific understanding of the nervous system, and reinforced by our own experience. We are quite confident in the function of this practice. Other practices are more difficult to justify. Inversions like Headstand and Shoulderstand were originally designed to prevent the falling of bindu from the head into the abdomen. Since that belief has fallen by the wayside, more modern practitioners try to ground the practices in physiological things like blood pressure or thyroid stimulation, which are questionable and unproven to the best of our knowledge. Yogic practices may be anywhere on this scale, swinging from 'traditional' to 'modern', and scientifically proven to completely debunked. Not to mention the experiences we have when we try these things for ourselves. We only suggest that you are considered and thoughtful when practicing yoga. This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. The second most common injury we see in the yoga world is of the hip. The damage happens when the hip bends (flexes) significantly. The thigh bone can bump against the bone of the pelvis and hip socket, crushing the cartilage there. This is called hip impingement. The injury generally happens in three progressive stages that may take months or years to develop. In the first stage, there is a slight or moderate pinching sensation as we pull the leg into the chest or rest the body onto the leg with gravity. This pinch is not the result of muscular engagement or tissue stretching, but of bone resting on bone and squishing the cartilage between. (There is a somewhat common instruction to 'feel a pinching sensation in the hip' in some postures. We recommend against this, for obvious reasons.)

If we continue to damage the cartilage beyond the second stage, in the third stage it can actually tear and pull away from the hip socket. This is called a labral tear, because the cartilage ring around the hip socket is the labrum. This injury can be quite painful, making it excruciating to do something as simple as walk. Like in the second stage, not only will the hip joint itself hurt, but the muscles of the thigh will struggle to function properly. Common postures that are in danger of causing this injury are those that involve deep hip flexion, which is bending of the hip joint. These include Wind Removing (pictured above), Bikram Triangle, Standing Bow, Half Tortoise, Separate Arms Balancing Stick and Spinal Twist (Ardha Matsyendrasana). Look at the position of the hip in all these postures. Notice that the deep flexion can cause the thigh bone to bump into the pelvis. How can we avoid, prevent or heal this injury? As with most things, prevention is the most effective method, as it will keep the body healthier and pain-free. To prevent this injury, pay close attention in any of these postures where your hip is deeply flexed. If you feel a pinching or pressure in the top/front of your hip, back off a bit. It can be challenging to separate this sensation from a stretching or engaged muscle, but the differentiation is quite clear once you notice it.

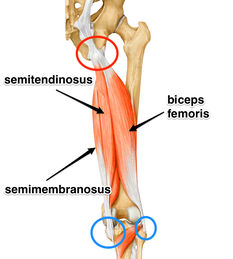

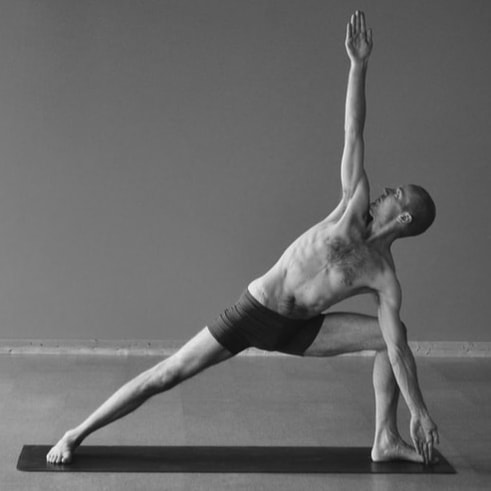

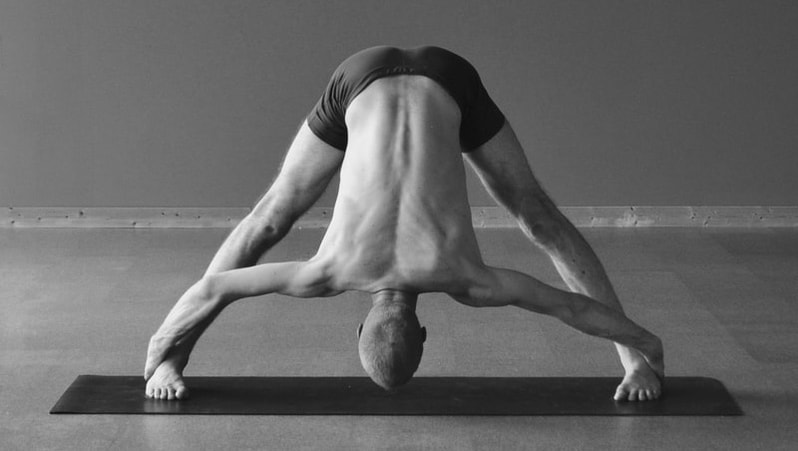

Anytime we use the arms to pull the leg deeper toward the pelvis, use great care! This is taking the hip joint past its normal range of motion, and is a common way to injure the hip. In most (perhaps all) situations, pulling will increase the risk of injury. Healing damaged hip cartilage is difficult. If you are only in Stage 1 or Stage 2, backing off of the postures will likely allow the body to heal. You will need to be conservative with the hip for awhile, at least six weeks. If you have a torn labrum, the conversation gets more complicated, as most will recommend surgical repair. The cartilage doesn't have a great blood supply, so it has trouble healing on its own. There are some stories of non-surgical success, but they are few and far-between. For us, the moral of the story is to be careful and gentle. Most people practice yoga to improve their health, and injury is the exact opposite of that.  This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. The single most common injury that we see in the yoga world is a hamstring attachment injury. It happens due to over-stretching the hamstrings. Since so many postures and exercises target this muscle group on the back of the thighs, what often ends up happening is we over-stretch and the tendon that attaches the hamstrings to the sit bones gets damaged. Quite often, we mistake this new, intense sensation for a "deeper" hamstring stretch, so we continue to push (or more often pull). This makes it worse, and many of us don't realize there is an injury until serious damage has been done. Stretching the hamstrings has become central to many styles of yoga. Like many other physical elements of modern practice, this emphasis comes from gymnastics, contortion and dance. In any given class, we may stretch the hamstrings from numerous positions: standing, seated, legs together, legs split, one leg, both legs, etc. This injury creates pain at the point where the hamstrings attach to the sit bones (ischial tuberosities), at the base of the pelvis in the back, pictured to the right and circled in red. It can be painful in forward folding positions, and may be sore after class so that it hurts to sit down. It is sometimes called "yoga butt". This injury is so common that almost half of yoga practitioners---men and women---have it currently or have had it in the past. Common postures that could strain the hamstrings are: Hands to Feet, Standing Separate Legs Stretching (pictured above), Standing Bow, Standing Splits, Stretching, Separate Legs Stretching and Tortoise, etc. Take a moment to notice the similarities in these positions, pictured below. They all tilt the pelvis forward with relationship to the femur (thigh bone). This makes the hamstrings long, which is why we feel the "stretching" in the back of the leg. The deeper these postures are, and the harder we push them, the more likely it will be to damage the attachment of the hamstrings. HOW TO HELP

First and foremost: rest. I know you don't want to hear this, and resting can be a real challenge for the mind and ego. This injury can take months or years to heal, and the more we aggravate it the longer it will take. Avoid forward folds for several months. Seriously! You can still do lots of other exercises and postures, but avoid forward bending of the hip for awhile. DO NOT STRETCH YOUR HAMSTRINGS! Second, don't overstretch the hamstrings, even after you're healed. The natural range of motion of the hamstrings only gets the femurs (thigh bones) to about 90 degrees with the pelvis when the knees are straight. This means that the vast majority of contortion-influenced yoga postures that "stretch" the hamstrings take it too far, which is why injury is so common. You might not be able to do Standing Splits with the same picturesque beauty, but you will be able to walk and sit without pain. Third, strengthen and shorten the hamstrings. We did a whole blog on this, where we explain a handful of postures and exercises that will make the legs strong and help prevent injury. These include Balancing Stick, Squatting, Bridge and Jastiasana. IN CONCLUSION The most important thing to take away from this is that you can get hurt from yoga practice. If you have pain at the back of your hip, the top of your hamstrings, at or near your sit bones, and this is exacerbated when you do forward folding postures, STOP IMMEDIATELY! It is very likely that you are damaging the upper attachment of the hamstrings. Take the time to let it heal, and then perhaps adjust your approach to the physical postures so that they have less likelihood of injury. Over the past few months, we have heard increasingly loud calls for talk about injury in yoga. So many students are hurt or have pain, and they don’t know what it is, how it happened or how to fix it. Some are even told by their teachers to push through the sensation to continue deepening the physical postures. After all, these exercises and postures are supposed to be healing, right? When we describe the common yoga injuries, students are both 1) shocked that you can get hurt doing yoga, and 2) surprised to hear us describing the pain and difficulty that they experience.

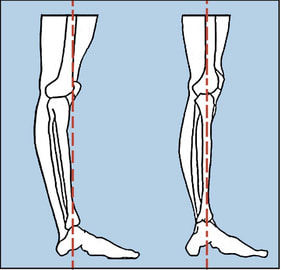

Yes, yoga can hurt you. It’s true. If you’ve practiced the physical forms of yoga that are popular in the West for more than a few months, chances are you’ve been injured or know someone who has. This is not to say that physical yoga practices are inherently dangerous or should be avoided. The same risk is present in virtually any physical activity: basketball, running, bowling. Anytime we use the body in a repetitive way and push it to go farther and farther, the risk of injury is quite high. We generally don’t know the limits of our capabilities until we go too far! Yoga is mostly thought of as a healing, healthy and therapeutic form of exercise, not to mention safe. Since most of us approach the practices thinking they will help us, we overlook the possibility for injury until it’s too late. It is especially true in the yoga world, where we want to believe that it only has the ability to make us better, more open, happier, peaceful versions of ourselves. The idea that any of these practices could injure our bodies, nervous systems or minds feels foreign and even contradictory. So all too often we disregard it. Until we get injured. Even then, we may think it was our fault, that we weren’t doing the practice right, because a “healing” practice couldn’t possibly be dangerous. But injuries are quite common in yoga. And each style has its own tendency toward certain imbalances, as the stress and repetition in each practice are a little different. We are going to do a whole series of posts about Injuries In Yoga. We will go into some depth about the most common injuries we see, which include hamstring attachment strain, hip impingement and labral tear, meniscus tear in the knee, supraspinatus damage in the shoulder, bicep tendon strain in the shoulder, sacroiliac instability in the low spine, and neck pain in the base of the neck. All of these can be created or exacerbated by physical yoga practices. For now, we want you to know that yoga can injure you, especially if you think it never will. Always take care and try to understand what you’re doing and why. Some intense sensations are safe and even beneficial, while others are not. Use caution and ask your teacher if you’re not sure. If they tell you that you won’t hurt yourself in yoga, get a new teacher. If you have an injury or had one in the past that you’d like to tell us about, please comment or message. Let us know your experience! "Locking the knee" is a concept in yoga that was popular in the 60s and 70s, including the styles of BKS Iyengar and Bikram Choudhury. It originally comes from weightlifting, where full extension of the knee joint and concerted contraction of the quadriceps are paramount. You will still hear weightlifters talk about "locking out" to refer to the full straightening of a joint that is under stress.

For the most part, this concept has dwindled in the yoga world due to the confusion it causes. There are at least 3 different meanings to the phrase "lock the knee," depending on what position you are in and who you're talking to. An anatomist has a different definition than a Bikram Yoga teacher. These are the three meanings: 1. CONTRACT THE QUADRICEPS This is the original meaning of the term as it comes from weightlifting and bodybuilding. Used in quadricep-heavy exercises like squats, "lock the knee" meant to straighten the knee as much as possible by squeezing the quadriceps with great force. In the yoga world, this has also become a way to relax or stretch the hamstrings, since engaging the quads naturally causes the hamstrings to disengage. In addition, it is sometimes believed that engaging the quadriceps, which causes the kneecap to lift up, will protect the knee joint from hyperextension. (It won't.) 2. RESTING THE FEMUR ON THE TIBIAL SHELF Anatomically speaking, a normal knee has the ability to hyperextend by a few degrees. It can go past the 180 degrees of a straight leg by about 4-6 degrees. When we are standing and our legs are bearing weight, we have the ability to hyperextend the knees and "rest" them on the tibial shelf. They settle back and the muscles of the leg relax, allowing us to stand for long periods of time without using much energy. When the knees are resting in this manner, they are "locked." To unlock them, there is a specific muscle (the popliteus) that unlocks the knees before they return to normal function. This definition of a "locked knee," which is essentially slight hyperextension, is often conflated with the first: contracting the quadriceps. Unfortunately, the combination of hyperextension and contracted quadriceps will accentuate the knee's tendency to hyperextend and possible create instability. 3. ENGAGING ALL THE MUSCLES AROUND THE KNEE Normally, the contraction of the quadriceps is accompanied by a relaxation of the hamstrings, and vice versa. It allows for effortless movement of the knee back and forth. But this relationship can be overridden with conscious effort and control, contracting both sets of opposing muscles simultaneously. In yoga parlance this is called a bandha, a "lock." When opposing muscle groups around a joint are consciously contracted together, the joint does not move. On the contrary, it becomes immobile and quite stable. This is often done to create stability and pressure gradients that effect the blood and heat flow in the body. IN CONCLUSION As you can see, the phrase "lock the knee" can mean a handful of different things. And it is important to note that the interpretations can conflict with one another. The first involves engaging the quadriceps while relaxing the hamstrings; the second involves relaxing both the quadriceps and the hamstrings; and the third involves engaging both the quadriceps and the hamstrings. Why do we, as yogis, practice physical postures?

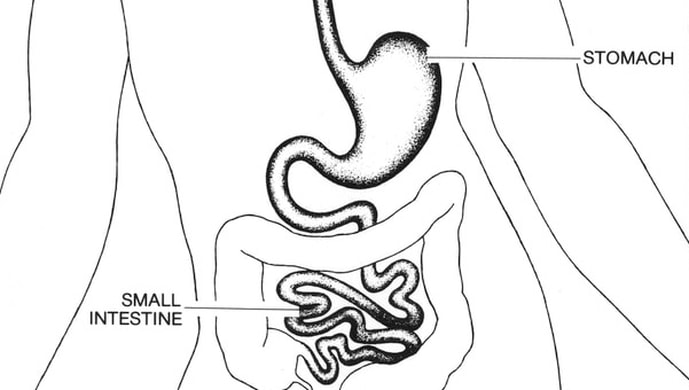

Depending on your goals, there may be a handful of answers to this important question. The exercises may increase your flexibility, increasing your ability to move the body without pain or limitation. They may help you relax, spending a little time each day focused only on your breathing and forgetting about your stress. They may help your balance, strength, blood pressure or sleep. At the center of all these motives is the spine, perhaps the single most important communication pathway of our body and mind. We can live without our arms and legs, but we cannot live without our spine. It provides structure, protection and support for our heart, lungs, organs and head. Almost every signal sent from around the body, from the fingers to the toes, makes its way to the central nervous system by way of the spinal cord. And almost every command about balance, movement or breath also travels via the spine. So every exercise, whether of the feet, arms, hips or abs is also an exercise of the spine. Even breathing exercises and meditation require communication through the spinal cord as we control our ribs, abdomen and posture. Paramhansa Yogananda called the spinal cord a "lightning rod for the divine." Our practices should contain plenty of attention to the health and function of the spinal column (the structural part) and cord (the nervous system part). We should keep the muscles of the spine strong and mobile, as well as doing what we can to protect the bones and discs strong; plenty of forward bending, backward bending and twisting. And we should also keep our awareness on the communicative aspects of the spine: its nerves. As one of our teachers said: "The arms and legs assist the posture. Every posture is in the spine." "Suck your stomach in!" goes a common instruction in yoga class. This cue is present in a lot of different lineages and styles, and goes to the heart of an important conversation in the yoga world: What are we teaching? Let's explore the meaning of this instruction, beginning with the elements involved. Namely, the "stomach" and "sucking in." What is the stomach? It is an organ in our digestive tract. It is high in the abdomen, just below the ribs and diaphragm. It is the first place our food goes after we chew and swallow it. How do we suck the stomach in? We don't. We can't. The stomach itself has muscles that help us in digesting and passing food through our system. But they are involuntary muscles that we can't consciously control. This instruction, "Suck the stomach in," refers to the stomach in a much more general and imprecise way, where "stomach" actually means "abdomen."

The muscle that pulls the abdomen in is called the transverse abdominis. It wraps around the belly like a corset, helping us breathe and stabilizing the spine when needed. If you are wondering what if feels like, exhale your breath forcefully and feel the sides of your abdomen. They will be tight and contracted. This is your transverse abdominis.

What are we actually teaching? That brings us back to the instruction, "Suck your stomach in." If we take the instruction at its word, it is impossible. The stomach's position cannot be changed consciously nor can its muscles be contracted consciously. The only way that this instruction makes sense is if we interpret "stomach" to mean "abdomen" and proceed to contract an abdominal muscle that "sucks in." Also, if our students take us at our word (which I hope they do), they are learning that the stomach is something that can be "sucked in," which it is not. This is worrying, essentially teaching an inaccurate and incorrect concept to unknowing students. The easiest of fixes This instruction can be modified ever so slightly to become an effective cue. "Pull your abdomen in" or "pull your belly in" are both anatomically sound and they accomplish the desired result: contraction of the transverse abdominis. They remove the danger of propagating false information to our students and encourage them to learn the correct way. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed