|

It has become popular in the sport, fitness and yoga worlds to drink alkaline water, water with a pH higher than regular water and higher than our blood. Some use alkalizing filters for their home or studio, while others buy alkaline water straight from the store in bottles.

The supposed benefits of drinking alkaline water range from better hydration and improving acid reflux to curing headaches and even cancer. But, according to a recent New York Times article, "there is no science to back it up." "Despite the claims, there’s no evidence that water marketed as alkaline is better for your health than tap water," the article says. There are two elements to look at here. The first is whether drinking alkaline water actually changes the pH of the body, and the second is whether a change in pH will provide benefits. The answer to both of these queries seems to be no. "Blood is tightly regulated at around pH 7.4." Our stomach secretes hydrochloric acid to digest our food and kill germs, and this acidic environment "quickly neutralizes" any alkaline substance before it makes its way into the rest of our digestive system or blood. So drinking water that is slightly alkaline won't affect the pH of our blood or body. Also, there no evidence that alkaline water provides health benefits. To the contrary, there are known risks including impaired growth and damage to cardiac muscle. "The only health effects that we know of are danger signs, so for people to continue to market alkaline water — they’re really as bad as the snake oil salesmen of yesteryear." We hope you stay hydrated, but you probably only need to drink regular water! Excerpts from: Is Alkaline Water Really Better for You? in the New York Times

10 Comments

We often get questions about how to hold the hand and fingers when doing Alternate Nostril breathing. As far as your nostrils are concerned, it doesn't matter how you hold the hand or what fingers you use. The only important part is breathing through one nostril at a time.

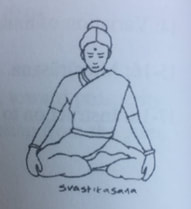

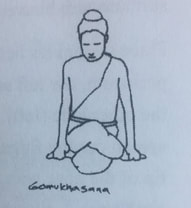

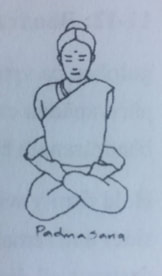

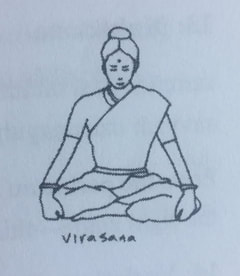

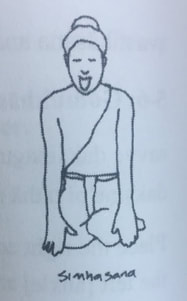

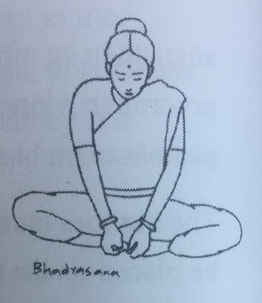

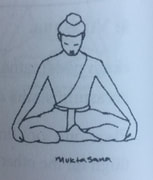

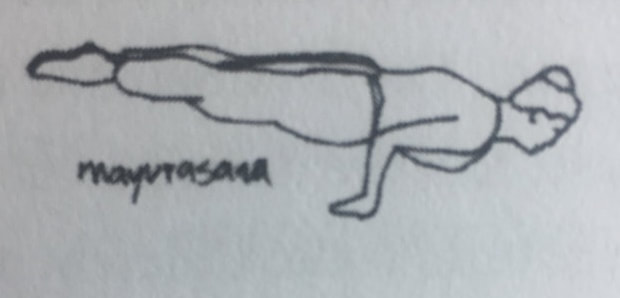

We start to need technique when we do the practice often and for long periods of time. For example, at Ghosh Yoga we practice Alternate Nostril breathing every morning for 30-60 minutes. When you hold your arm and hand in position for that long, it can get tired and sore if you're not careful. FINGERS The most common way to hold the hand is with the pointer and middle fingers curled into the palm, as pictured above. The thumb then closes one of the nostrils and the pinky and ring fingers close the other. This formation of the hand allows the wrist to be straight as you manipulate the nostrils, meaning greater comfort and wrist health over time. If you use your pointer finger to close the nostril, you will find that it forces the wrist to cock at a strange angle. This may be fine for short practices, or if you don't do it often. But over time you will find that the wrist becomes sore and achy. RIGHT OR LEFT People also ask about using the right or left hand. Either is fine. Traditionally the practices are taught with the right hand because the left hand was used to clean the body after using the bathroom. So eating, touching the face or another person with the left hand was culturally unacceptable. This is why the right hand is generally used. Since bathroom practices have changed, as have hand washing practices, it is acceptable to use the left hand for this practice. It is also acceptable to change arms and hands if one gets tired. This is almost inevitable if you do the practice for more than 5 or 10 minutes. The Yoga Yajnavalkya is an early text of hathayoga, circa 1300CE. It is one of the few early texts with more than one or two asanas (postures) described. It has 8. It is worth noting that 7 of the 8 postures are seated, none are standing. Only Mayurasana (Peacock Posture) is not seated. It is also worth noting that Padmasana (Lotus Posture) is instructed with the arms bound behind the back.

Excerpts from Yoga Yajnavalkya, translated by A.G. Mohan with Ganesh Mohan

Over the past two months, we have uprooted our lives, moving out of a house that's been in my family for decades and into a small apartment that will enable us to be more mobile. Throughout the process I have been reminded of 3 disparate teachings from 3 different sources that all point to the same idea: that a yogi becomes invisible.

We often talk about "drawing toward" and "pushing away," so much that it was even the topic of a blog last year. When we are compelled to draw things toward us, whether they are objects, money or the attention of others, we fortify the constructs of our personality and take ourselves further from liberation (the essential, non-constructed version of the self). These things make us bigger, sometimes literally and sometimes theoretically. As we remove these constructs, the yogi becomes "smaller" until she approaches invisibility. Looking back into history, the yogasutras state that suffering comes from pairs of opposites (2:48), including hot and cold, good and bad, etc. When we adhere to the pairs of opposites, swinging from happy to sad and back again, we are like a tight-rope walker who is wobbling violently from side to side. As we reduce our movement from side to side, we approach stillness in the middle, which from the outside can seem like nothing is happening. But the stillness reveals deeper movement that was imperceptible when the action was bigger. The more centered the yogi becomes, the more still she is. She approaches invisibility through her lack of drastic shifts. Most literally, this was said to us by Tony Sanchez, one of our teachers. During our time with him, he told us that "a yogi becomes transparent, almost invisible." This is contrary to our culture, in which we become more visible and famous as success increases. The yogi, on the other hand, does not pursue worldly gain or the admiration of others. Quite the opposite. As the yogi progresses, she has less and is attached to less. So I ask you: Do you draw things toward yourself? Do you embrace the pairs of opposites? Do you pursue the admiration of others? Do you make yourself still? Are you invisible? True forward bending of the spine can be a source of great physical benefit. There is some subtlety involved, as doing a forward bend is not the same as just using gravity to forward fold. However, once this practice is implemented, one can experience many benefits. Here are 5 reasons to practice forward bending:

5. Maintain range of motion: For many of us, we don’t struggle with simple actions like tying our shoes… yet! Without maintaining (or trying to increase) range of motion we may come to the point where we can’t bend over enough to pick something up off the floor or tie our own shoes. Regular practice of forward bending the spine can help! 4. Lower your heart rate: Forward bending stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system. Because of this, it can have a positive affect on lowering a high heart rate. 3. Strengthen your abdominal muscles: Many of us have very weak abdominal muscles. This is partially because we sit in chairs for so many hours a day. As we sit, we generally don’t maintain upright posture and our abdomen stays relaxed for hours on end. It doesn’t take long before our body forgets how to use it. Forward bending requires that you use your abdomen— specifically the rectus abdominis. By forward bending the spine, we can remind the body how to use this muscle and build the strength we all need. 2. Release your tight back: Many people live with a tight low back which can be very uncomfortable. Since the abdominal muscles act reciprocally to the back muscles, we can ease the back by strengthening and engaging the abs. 1. Calm down: When we forward bend, it has a calming effect on the body. Since many people are overstimulated, take in a lot of caffeine and have very high stress levels, forward bending is a great and simple way to feel calmer and more relaxed. There is a fine line between teaching someone and insulting them.

It is no surprise that being a teacher involves telling people things that they don't know. This can range from a simple addition of new knowledge - by far the easiest for the student to integrate - to the shifting of concept or understanding, which is much harder for any student to do. Anytime we have to reorganize our belief system or reconfigure how we look at a problem, it requires significant effort and faith from us. This is largely due to our "confirmation bias," a mental phenomenon which causes all of us to adopt beliefs that confirm what we already think and ignore anything that conflicts. As teachers, we always have to tread lightly when correcting people, since they are doing the best they can, using every ounce of their intelligence to be all they can be. When we step in and tell them that they are doing something wrong, we can unknowingly tread on deep-held beliefs and long-held habits. Every time we correct a student, we are basically telling them they are wrong, which no one likes to hear. We can put our students on the defensive through the simple act of trying to help them. For the student, it is rarely as simple as just changing what they do and how they think, which is why students often adjust to our instruction in the moment and then go right back to doing what they were doing. In these instances, we have not made any progress in instructing the student, since they have not made any progress in their understanding. The way around this is not to avoid correcting our students, but to approach them like we are on their team instead of a superior who is "fixing" them. We must keep in mind that they are doing what they think is right. If they knew they were doing something wrong, they would change it immediately. We are not "correcting" them, but giving them an opportunity to improve. And who doesn't readily accept an opportunity to improve? We are all happy when our practice seems to be progressing nicely: We learn quickly, our understanding evolves, our abilities increase. On the other hand, we all have periods of frustration, when our efforts seem to bear no fruit, either physically or mentally. Even more infuriating can be periods when we are unable to practice at all due to busyness, injury or some other force.

During these periods of frustration, it is important to remember: yoga practice is an ultra-marathon, not a sprint. In the scheme of our whole practice and our whole life, having a bad week, month or even year is a small thing. What is significant is that we regain our determination and continue. Believe it or not, yogis burn out as often as they fizzle. We begin with such passion and vigor that we practice too much and too hard. At first this leads to tremendous progress in a short period of time, but it is unsustainable. We trim our practice back to an ordinary amount and become frustrated by the slowness of the progress. Practice loses its excitement, and we are too worn out to continue. We recently asked one of our teachers (Swami Shambhudevananda) about this. He reminded us that yogic burnout is common. The remedy is to rest, recover and revisit your inspirations. Don't be derailed by the ebbs and flows in your practice. If we practice long enough, ups and downs are to be expected. They are simply a sign of a mature practice. Don't lose hope, and certainly don't stop the practice! It may seem like a simple and obvious question: what are we really teaching? But if we look a little deeper, we may find that our intentions can conflict with what we are teaching our students.

The simplest answer to this question for modern Western yogis is: asana, postures. We teach physical practices for the health benefits of mobility and flexibility, strength, balance and inversion. We also teach breathing, which can slow the heart rate, lower the blood pressure and reduce stress. The physical, mental and nervous system benefits of yoga practice are real, and they are increasingly central to the yoga culture. This only creates an ideological conflict when we claim to be teaching anything like traditional yoga. The systems of yoga are many, but prior to a few hundred years ago most were dedicated to the subordination of the body and senses in favor of the realization of the true nature of the self. Do you see the conflict between these two ideas? When we practice modern physical yoga, it is often alongside confidence-building rhetoric that values personal experience. "Have faith in yourself," "You are your own best teacher," we may tell our students. These things build our identification with our bodies and the physical practices, working against the progress of dis-identifying with the body. So, in a traditional sense, a physically-focused practice centered on accomplishing postures, and even health, can work against the ideals of yoga. Admittedly, this is complicated. We are not suggesting that you change the way you teach or the way you approach your practice. But it is worth noting some of the little conflicts and paradoxes that arise in our yoga. These conflicts shed light on our assumptions and allow us to refine our view of ourselves and the world. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed