|

It can be difficult to know what is real in this world. The methods of yoga, spirituality and science have developed to explore this question. Sometimes they come to the same answers, but sometimes they contradict.

As yoga teachers, we are often confronted with the problems of: 'Why do we do these things?' and 'What is right?' We usually look in three places to find answers: tradition, science and personal experience. TRADITION We at Ghosh Yoga are fascinated with tradition, and we have researched it, studied it, lectured on it and challenged it. We have written about the relationship of oldness and tradition, the Spirit of Tradition, and the sometimes misleading value of tradition. With regards to these questions---what is real? and what is worth learning?---tradition plays an important role in yoga. Many of us are drawn to yoga because of its ancientness, sacredness and gravity. And the idea of lineage, teaching in the same way as you were taught, is a time-worn Indian method that has come to the West with yoga. At its best, a lineage links modern students with ancient teachers and sages. We must take these things seriously. What did our teachers think and what did they teach?If we look in older texts, what was being taught hundreds or thousands of years ago? Most importantly, how do these apply to modernity? Can we extrapolate our own situations, thoughts and perspectives from ancient teachings? SCIENCE In the past few centuries, scientific methods have developed that are centered around the reliability and repeatability outcomes. The sciences have improved our understanding of anatomy, physiology, biomechanics and neurology among other things. We can apply this knowledge to the body and mind in yoga practice. But it can sometimes come into conflict with traditional understanding. For example, humans did not know the intricacies of bodily anatomy until the 15th century CE. This is clearly depicted in art from earlier, where the body is only really understood by looking from the outside. Take this one step further inward, to the functioning of breathing, energy or the nervous system. These things have come into focus even more recently in human history. Therefore, when we look to 'tradition' for physical, anatomical or physiological methods, we must take great care. How does the ancient understanding line up with modern understanding? If there is a discrepancy, is it clear where, why or when that may have occurred? And which do we trust? (For the past few decades, increasing numbers of scientific studies are being done on the practices of yoga. Check out Pure Action.) PERSONAL EXPERIENCE It may seem obvious to say, but all of these practices and traditions of yoga are intended to be put to use by actual living humans, like us. They only come to life when they are studied and executed. Those experiences we have and the inner knowledge we gain are hugely valuable, and one might argue that they are the central purpose of it all. On the other hand, the root of all the spiritual traditions is that our ordinary knowledge and perception are lacking and misleading. We must look deeper and strive to understand what is difficult and hidden. So, partly, our experience is the most important element, but it can also be the most misleading if we are not careful. TAKING THE THREE TOGETHER When assessing the methods and goals of yoga, we constantly weigh the contributions of these three elements: tradition, science and personal experience. There are some instances when all three align. This is the case with Alternate Nostril breathing, a practice described in the ancient texts, explained clearly with the modern scientific understanding of the nervous system, and reinforced by our own experience. We are quite confident in the function of this practice. Other practices are more difficult to justify. Inversions like Headstand and Shoulderstand were originally designed to prevent the falling of bindu from the head into the abdomen. Since that belief has fallen by the wayside, more modern practitioners try to ground the practices in physiological things like blood pressure or thyroid stimulation, which are questionable and unproven to the best of our knowledge. Yogic practices may be anywhere on this scale, swinging from 'traditional' to 'modern', and scientifically proven to completely debunked. Not to mention the experiences we have when we try these things for ourselves. We only suggest that you are considered and thoughtful when practicing yoga.

1 Comment

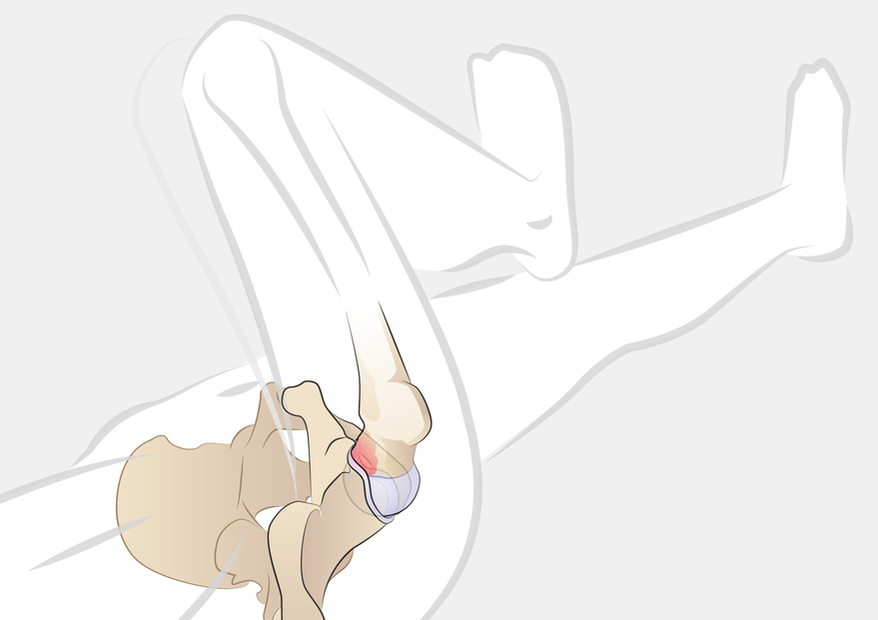

This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. The second most common injury we see in the yoga world is of the hip. The damage happens when the hip bends (flexes) significantly. The thigh bone can bump against the bone of the pelvis and hip socket, crushing the cartilage there. This is called hip impingement. The injury generally happens in three progressive stages that may take months or years to develop. In the first stage, there is a slight or moderate pinching sensation as we pull the leg into the chest or rest the body onto the leg with gravity. This pinch is not the result of muscular engagement or tissue stretching, but of bone resting on bone and squishing the cartilage between. (There is a somewhat common instruction to 'feel a pinching sensation in the hip' in some postures. We recommend against this, for obvious reasons.)

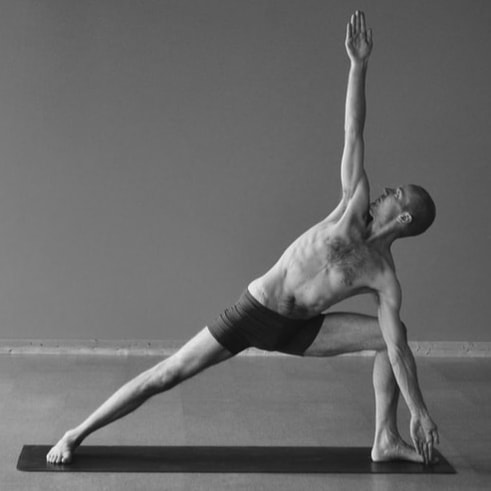

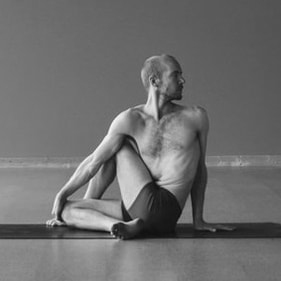

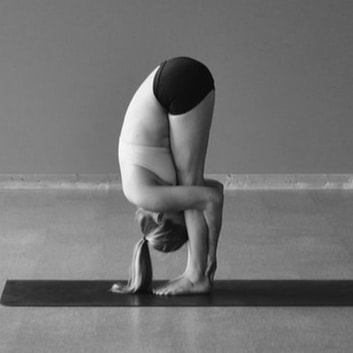

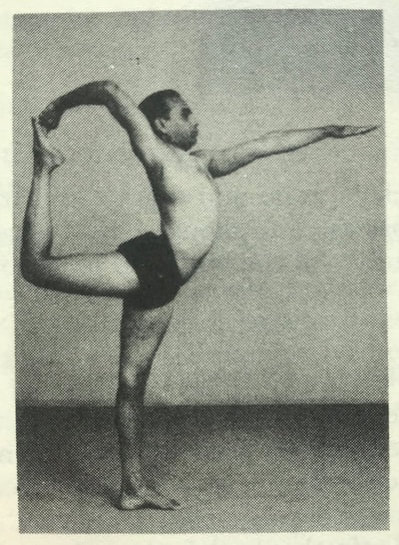

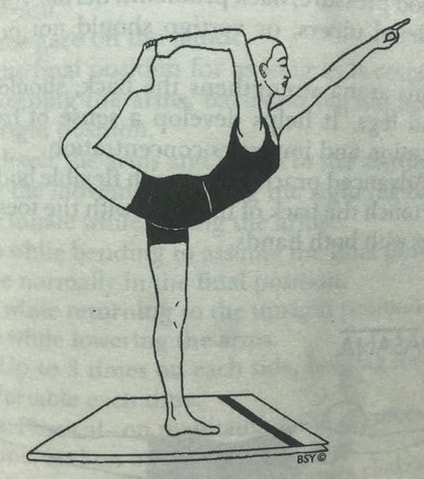

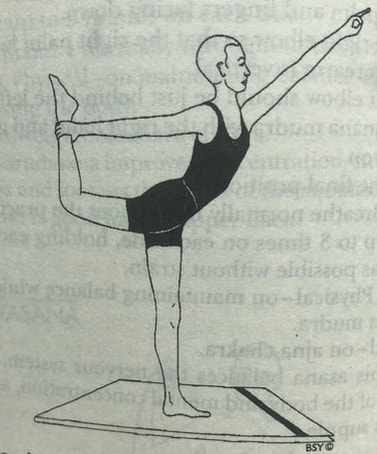

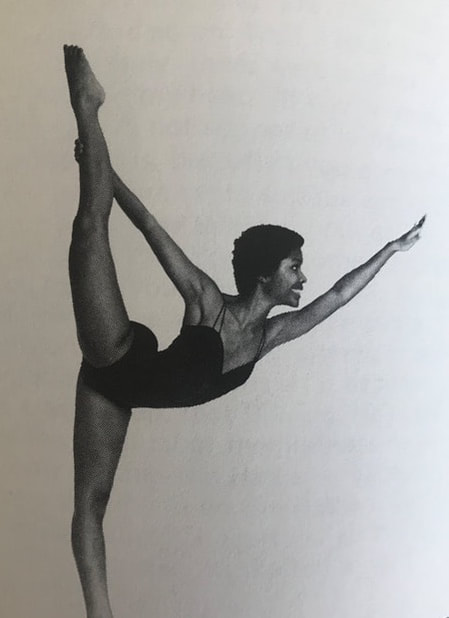

If we continue to damage the cartilage beyond the second stage, in the third stage it can actually tear and pull away from the hip socket. This is called a labral tear, because the cartilage ring around the hip socket is the labrum. This injury can be quite painful, making it excruciating to do something as simple as walk. Like in the second stage, not only will the hip joint itself hurt, but the muscles of the thigh will struggle to function properly. Common postures that are in danger of causing this injury are those that involve deep hip flexion, which is bending of the hip joint. These include Wind Removing (pictured above), Bikram Triangle, Standing Bow, Half Tortoise, Separate Arms Balancing Stick and Spinal Twist (Ardha Matsyendrasana). Look at the position of the hip in all these postures. Notice that the deep flexion can cause the thigh bone to bump into the pelvis. How can we avoid, prevent or heal this injury? As with most things, prevention is the most effective method, as it will keep the body healthier and pain-free. To prevent this injury, pay close attention in any of these postures where your hip is deeply flexed. If you feel a pinching or pressure in the top/front of your hip, back off a bit. It can be challenging to separate this sensation from a stretching or engaged muscle, but the differentiation is quite clear once you notice it.

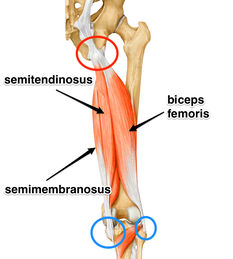

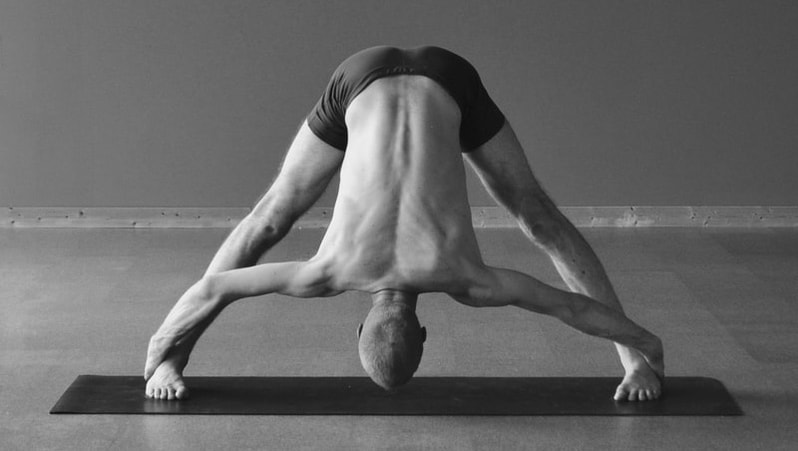

Anytime we use the arms to pull the leg deeper toward the pelvis, use great care! This is taking the hip joint past its normal range of motion, and is a common way to injure the hip. In most (perhaps all) situations, pulling will increase the risk of injury. Healing damaged hip cartilage is difficult. If you are only in Stage 1 or Stage 2, backing off of the postures will likely allow the body to heal. You will need to be conservative with the hip for awhile, at least six weeks. If you have a torn labrum, the conversation gets more complicated, as most will recommend surgical repair. The cartilage doesn't have a great blood supply, so it has trouble healing on its own. There are some stories of non-surgical success, but they are few and far-between. For us, the moral of the story is to be careful and gentle. Most people practice yoga to improve their health, and injury is the exact opposite of that.  This is part of a series about Injuries In Yoga. The single most common injury that we see in the yoga world is a hamstring attachment injury. It happens due to over-stretching the hamstrings. Since so many postures and exercises target this muscle group on the back of the thighs, what often ends up happening is we over-stretch and the tendon that attaches the hamstrings to the sit bones gets damaged. Quite often, we mistake this new, intense sensation for a "deeper" hamstring stretch, so we continue to push (or more often pull). This makes it worse, and many of us don't realize there is an injury until serious damage has been done. Stretching the hamstrings has become central to many styles of yoga. Like many other physical elements of modern practice, this emphasis comes from gymnastics, contortion and dance. In any given class, we may stretch the hamstrings from numerous positions: standing, seated, legs together, legs split, one leg, both legs, etc. This injury creates pain at the point where the hamstrings attach to the sit bones (ischial tuberosities), at the base of the pelvis in the back, pictured to the right and circled in red. It can be painful in forward folding positions, and may be sore after class so that it hurts to sit down. It is sometimes called "yoga butt". This injury is so common that almost half of yoga practitioners---men and women---have it currently or have had it in the past. Common postures that could strain the hamstrings are: Hands to Feet, Standing Separate Legs Stretching (pictured above), Standing Bow, Standing Splits, Stretching, Separate Legs Stretching and Tortoise, etc. Take a moment to notice the similarities in these positions, pictured below. They all tilt the pelvis forward with relationship to the femur (thigh bone). This makes the hamstrings long, which is why we feel the "stretching" in the back of the leg. The deeper these postures are, and the harder we push them, the more likely it will be to damage the attachment of the hamstrings. HOW TO HELP

First and foremost: rest. I know you don't want to hear this, and resting can be a real challenge for the mind and ego. This injury can take months or years to heal, and the more we aggravate it the longer it will take. Avoid forward folds for several months. Seriously! You can still do lots of other exercises and postures, but avoid forward bending of the hip for awhile. DO NOT STRETCH YOUR HAMSTRINGS! Second, don't overstretch the hamstrings, even after you're healed. The natural range of motion of the hamstrings only gets the femurs (thigh bones) to about 90 degrees with the pelvis when the knees are straight. This means that the vast majority of contortion-influenced yoga postures that "stretch" the hamstrings take it too far, which is why injury is so common. You might not be able to do Standing Splits with the same picturesque beauty, but you will be able to walk and sit without pain. Third, strengthen and shorten the hamstrings. We did a whole blog on this, where we explain a handful of postures and exercises that will make the legs strong and help prevent injury. These include Balancing Stick, Squatting, Bridge and Jastiasana. IN CONCLUSION The most important thing to take away from this is that you can get hurt from yoga practice. If you have pain at the back of your hip, the top of your hamstrings, at or near your sit bones, and this is exacerbated when you do forward folding postures, STOP IMMEDIATELY! It is very likely that you are damaging the upper attachment of the hamstrings. Take the time to let it heal, and then perhaps adjust your approach to the physical postures so that they have less likelihood of injury. Over the past few months, we have heard increasingly loud calls for talk about injury in yoga. So many students are hurt or have pain, and they don’t know what it is, how it happened or how to fix it. Some are even told by their teachers to push through the sensation to continue deepening the physical postures. After all, these exercises and postures are supposed to be healing, right? When we describe the common yoga injuries, students are both 1) shocked that you can get hurt doing yoga, and 2) surprised to hear us describing the pain and difficulty that they experience.

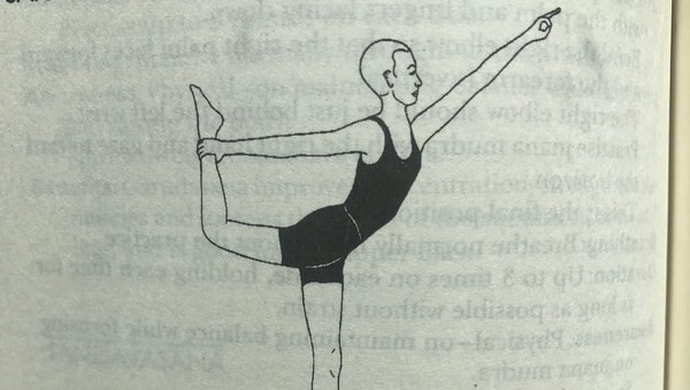

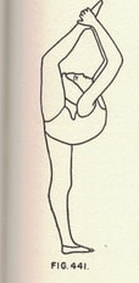

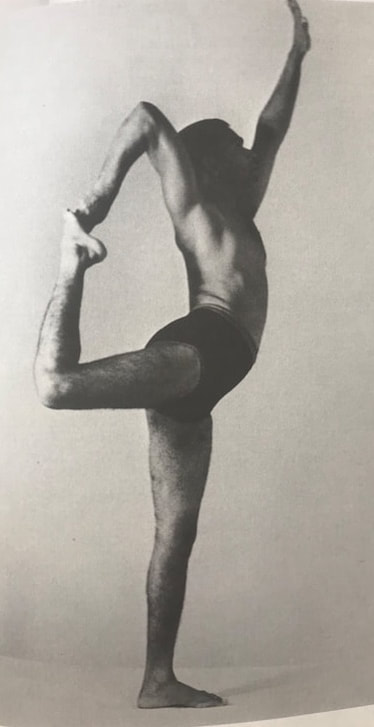

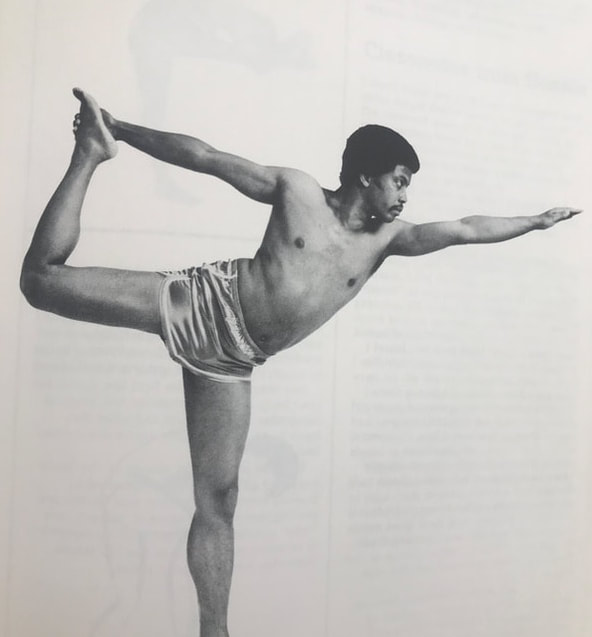

Yes, yoga can hurt you. It’s true. If you’ve practiced the physical forms of yoga that are popular in the West for more than a few months, chances are you’ve been injured or know someone who has. This is not to say that physical yoga practices are inherently dangerous or should be avoided. The same risk is present in virtually any physical activity: basketball, running, bowling. Anytime we use the body in a repetitive way and push it to go farther and farther, the risk of injury is quite high. We generally don’t know the limits of our capabilities until we go too far! Yoga is mostly thought of as a healing, healthy and therapeutic form of exercise, not to mention safe. Since most of us approach the practices thinking they will help us, we overlook the possibility for injury until it’s too late. It is especially true in the yoga world, where we want to believe that it only has the ability to make us better, more open, happier, peaceful versions of ourselves. The idea that any of these practices could injure our bodies, nervous systems or minds feels foreign and even contradictory. So all too often we disregard it. Until we get injured. Even then, we may think it was our fault, that we weren’t doing the practice right, because a “healing” practice couldn’t possibly be dangerous. But injuries are quite common in yoga. And each style has its own tendency toward certain imbalances, as the stress and repetition in each practice are a little different. We are going to do a whole series of posts about Injuries In Yoga. We will go into some depth about the most common injuries we see, which include hamstring attachment strain, hip impingement and labral tear, meniscus tear in the knee, supraspinatus damage in the shoulder, bicep tendon strain in the shoulder, sacroiliac instability in the low spine, and neck pain in the base of the neck. All of these can be created or exacerbated by physical yoga practices. For now, we want you to know that yoga can injure you, especially if you think it never will. Always take care and try to understand what you’re doing and why. Some intense sensations are safe and even beneficial, while others are not. Use caution and ask your teacher if you’re not sure. If they tell you that you won’t hurt yourself in yoga, get a new teacher. If you have an injury or had one in the past that you’d like to tell us about, please comment or message. Let us know your experience! A couple years ago we did a comparison of all the postures in significant publications from the Ghosh yoga lineage. There were a couple of surprises in that search. One of the most significant was the complete absence of Standing Bow Pulling posture in any of the texts. Why was this posture missing? Where and when did it come from? And how did it become so central to Bikram Choudhury's system of 26 postures that he developed in the 1970s? Upon further research, it seems that Standing Bow Pulling posture is a descendant of a more difficult position, Lord of the Dance. But even Lord of the Dance is a recent addition to the yoga canon, appearing only in the 1950s or '60s. It seems that Lord of the Dance popped up in south India, perhaps coming from Indian dance, contortion and gymnastics, and quickly spread. Its transition toward Standing Bow Pulling didn't come until late in the 1960s. Let's start at the beginning... Obvious as it may be to state, Standing Bow Pulling and its predecessor Lord of the Dance posture (Natarajasana) are nowhere to be found in the pre-modern texts of yoga. As physical postures were becoming more prominent throughout the development of hathayoga, they were largely seated or lying positions. Almost no postures in hathayoga are done standing. Even as we entered the 20th century and the fathers (sadly we don't know of many mothers) of modern yoga revolutionized the discipline, the acrobatics and deep stretching that we recognize today were still scarce. Early pioneers like Yogendra, Kuvalayananda, Krishnamacharya, Shivananda of Rishikesh, Bishnu Ghosh and Buddha Bose greatly expanded the number of positions in "yoga" through the 1920s, '30s and '40s, but still there was nothing resembling Standing Bow Pulling. At that point, yoga was largely adopting the practices of calisthenics and marrying the breath with relatively simple movements of the body.

IN CONCLUSION This all makes Choudhury's Standing Bow Pulling posture fascinating and very new. It seems to be based on a modification or preparation for Lord of the Dance, which itself is a recent addition to the yoga asana canon. And further, this variation continues to be deepened and elaborated until it has become essentially a new posture in its own right. 1. Goldberg, Elliott. The Path of Modern Yoga. p395

2. Swami Satyananda Saraswati. Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. 2012 (1969). Hardly a day goes by when someone doesn't ask us, "Is Bikram Yoga the same as Ghosh Yoga?" It is a valid and interesting question, as plentiful yoga systems seek to separate themselves from the competition with novel methods and attributes. The two methods are closely related, since Bikram Choudhury learned at Ghosh's College. But there are some fundamental differences that keep the two systems from being synonymous.

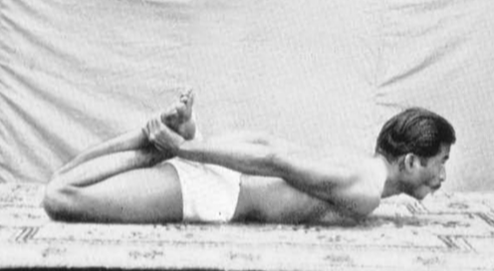

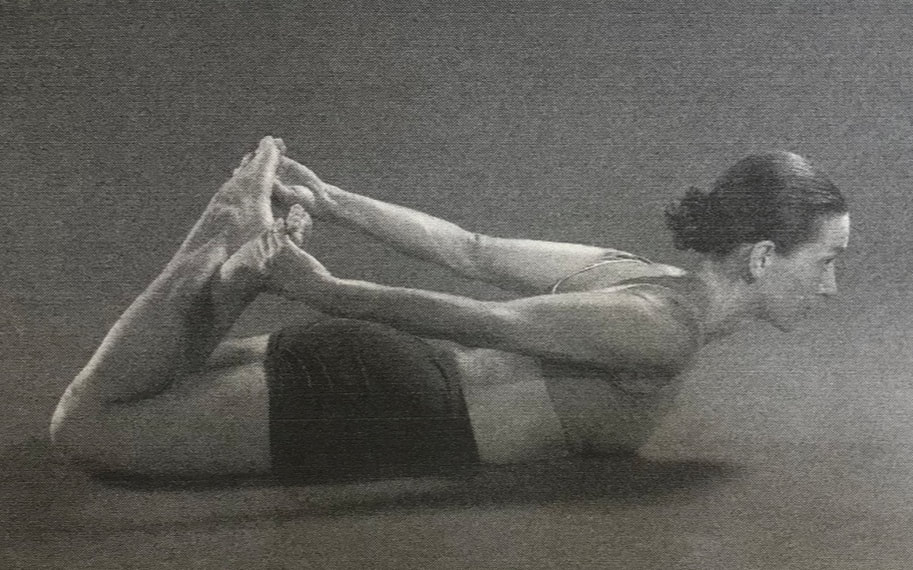

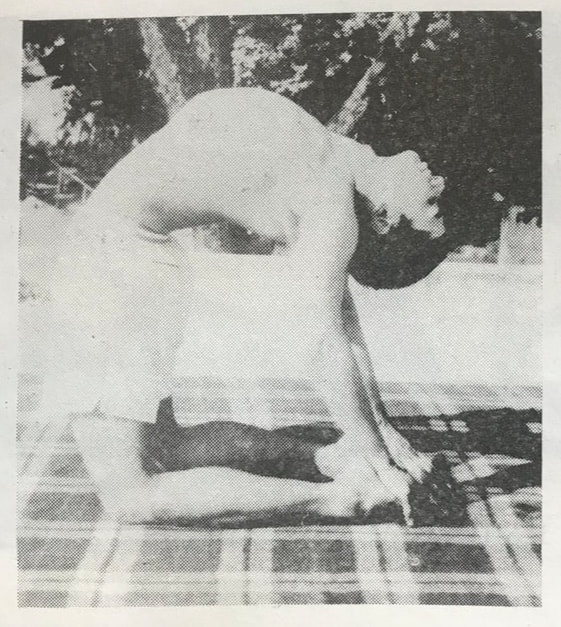

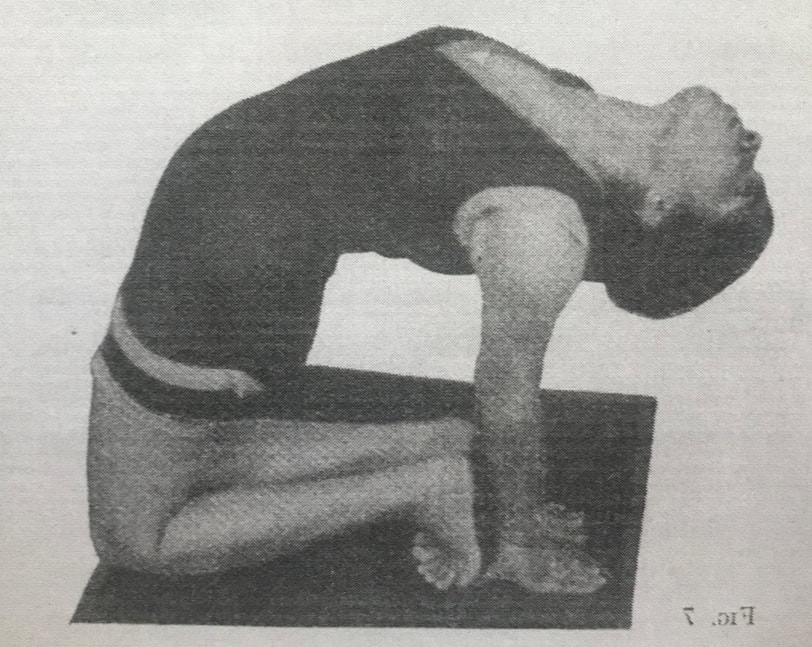

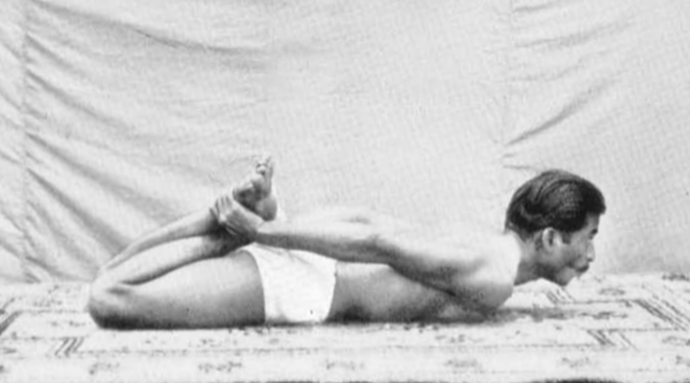

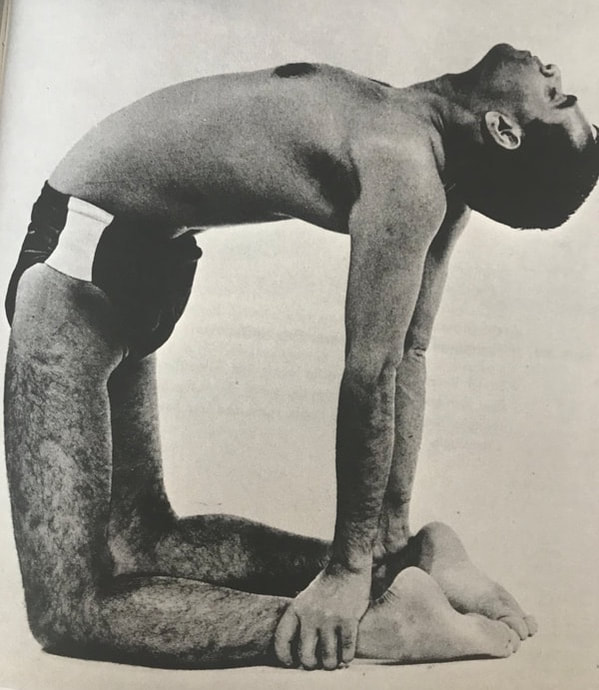

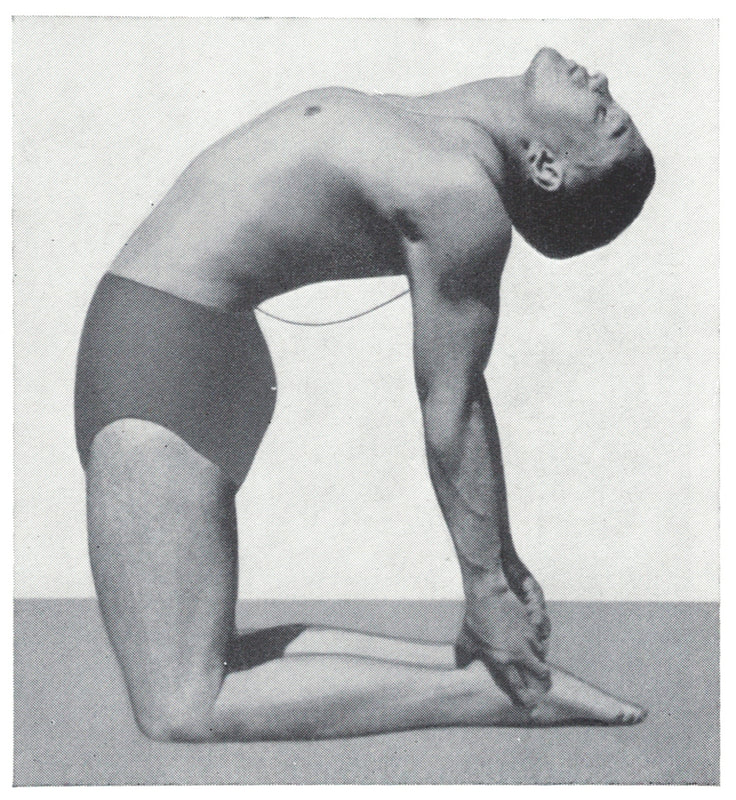

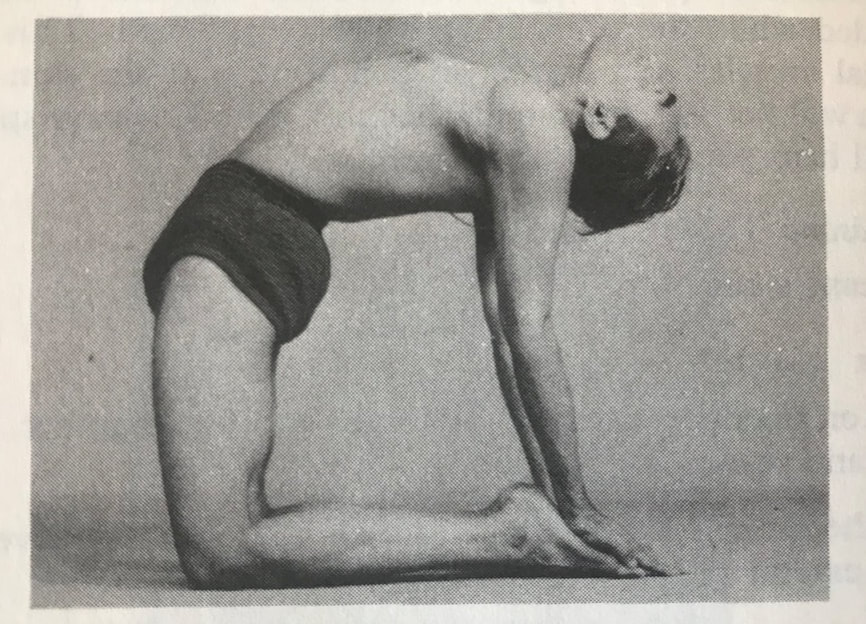

First, let's look at what they have in common. THE POSTURES Most of the exercises in Bikram Yoga are recognizably from the Bengal region of India, where Ghosh's College is located. The previous students of Ghosh taught these same postures and exercises like Half Tortoise, Rabbit and Standing Head to Knee. And several of the postures, like Stretching, Cobra, Locust, Bow and Corpse, are traditional yoga asanas found in older texts. Notably missing from both Bikram and Ghosh yogas are exercises like Up-dog, Down-dog and Warriors One and Two which come from South India and have made their way into most vinyasa yoga styles. STILLNESS Another element shared between Bikram and Ghosh yogas is the alternation of effort and rest. Each posture is held in stillness for a brief period and followed by an equal portion of relaxation. While standing, the practitioner simply stands still, though some of the older Ghosh students insisted on lying down between exercises. During postures on the floor, relaxation happens by assuming the Corpse posture. This is a distinctive element of these styles, setting them apart from the popular flowing methods that link stationary positions with fluid movements and Sun Salutations. THERAPEUTIC INTENT It can seem obvious, but both Bikram and Ghosh yogas are fundamentally designed to help the student be healthy. This is similar to all the yoga in Bengal, where the postures are done to help the organs, circulation, digestion or some other element. They generally have a therapeutic purpose. This intention can be contrasted with many vinyasa styles of yoga that originated in the performative gymnastics of Mysore. Those styles, like Ashtanga Vinyasa and its descendant "flow" methods, have become more therapeutically focused over the ensuing decades. But the origin of flowing yoga was performative. Now, let's look at what is different between Bikram Yoga and Ghosh Yoga. SET INSTRUCTIONS The method of Bikram's yoga is largely defined by its style of instruction, the rote utterance of prewritten commands. Teachers of the style can be judged by the quality of their "dialogue." Many paraphrases and copycats have popped up, but Bikram's original is still considered by most to be the gold standard. This rote instructional style is nowhere present in the teachings of Ghosh Yoga, where the majority of verbal instruction is simply counting the duration of each exercise. HEAT Also central to Bikram's style is a heated room, a characteristic that finds no expression in other manifestations of Ghosh's style. In India, they turn on fans or air conditioning when the day gets hot, or they forego the scorching parts of the day altogether. A SET SEQUENCE The two differences above are somewhat peripheral to the essence of the methods. The irreconcilable difference between these two systems is Bikram Yoga's unchanging set of exercises. The same 26 postures are "prescribed" for every student no matter their age, ability, experience, goals or ailments. Central, indeed fundamental, to the Ghosh system is a unique prescription for each student. It would be unheard of to assign the same practices to different people, especially without learning their strengths and weaknesses. Because Bikram Yoga is defined by its specific and repeated set of postures, and Ghosh Yoga is defined by its attention to the individual, it is impossible to conclude that Bikram Yoga and Ghosh Yoga are the same thing. They certainly share several key elements, namely their postures, the alternation of effort and relaxation, and therapeutic intent. But the defining characteristics of Bikram Yoga like rote instruction, added heat and especially a single unchanging set of exercises separate it substantially from Ghosh Yoga. Camel Posture, Ushtrasana, has at least 300 years of history in yoga texts. But the posture changed drastically in the mid-20th century from the traditional prone position (as pictured above) to the kneeling backbend that most modern yogis will recognize. This shift from prone to kneeling happened over the course of a few decades between 1920 and 1960. Prior, Camel Posture was a posture done on the belly. After 1960 it is done on the knees. In between, one might find instruction for either. Below we have elaborated 8 versions of the posture that show its irregular progression through these decades.

Buddha Bose (1938): Bose instructs the posture as in the Gheranda Samhita, lying on the belly. Like many of his other instructions, Bose draws directly from Sivananda, comparing the posture to Dhanurasana, Bow Posture. Sadly, Bose does not have a photo. "Lie on the abdomen...bend the legs backward from the knees...with the hands firmly grasp the ankles. Now lift the head." The only difference between the two postures, he says, is "do not raise the knees and thighs off the floor" in Camel.

IN CONCLUSION

It is possible that these two positions are unrelated, connected only by their name. It is difficult to explain why the abdominal Camel Posture was phased out at the same time as the kneeling Camel Posture was phased in. Since about 1960, the kneeling version is ubiquitous. But the older texts including the Gheranda Samhita and those by Sivananda, Buddha Bose and Yoga Mimamsa clearly instruct the same position, lying on the belly with crossed legs. Sita Devi's book from 1934 is the outlier here, with instruction of the kneeling version in such an early decade. Also difficult to explain is the divergence between Bose and Mukerji, who were both students of BC Ghosh in Kolkata. In the 1930s, Bose describes Camel as lying on the belly, while Mukerji does it kneeling only 30 years later in 1963. When we practice yoga postures, we might be doing them for different reasons. We may be trying to reduce the pain in our backs, improve our balance, burn a few calories or experience a deeper spirit within. These are drastically different goals, and we can't use the same techniques to achieve them all. Hundreds of "yoga" postures and practices exist these days, and they don't all attain the same things. As you practice, think carefully about what you are trying to accomplish, and use those postures that will help. Here are the 5 different types of yoga postures:

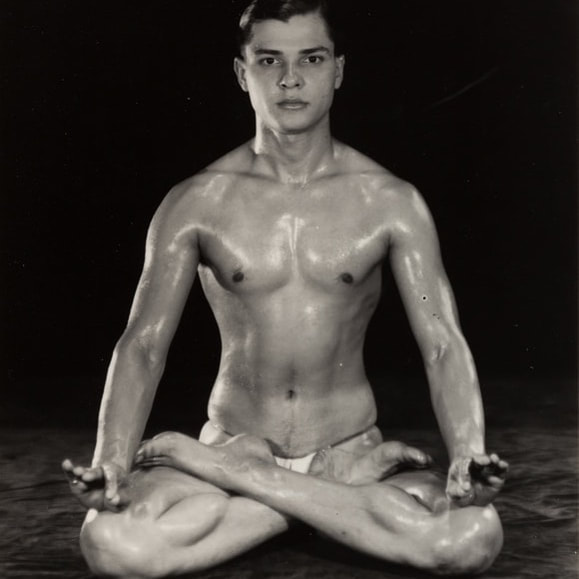

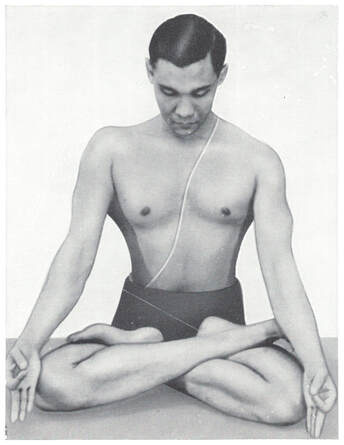

1. Seated, meditation postures. These are the oldest, most traditional yoga postures. When the Yoga Sutras (or any text that is more than 1,000 years old) refer to asanas, this is what they mean: a seated, upright, stable and relaxed position. These positions are not used for their own benefit or to create health, but to facilitate the more internal practices of breath control and meditation. These are the quintessential "yoga postures," Lotus and Siddhasana. 2. Positions to prepare the body for seated meditation or help the body recover from it. As anyone who has tried to sit still for a long period of time knows, it is difficult for the body. A certain amount of flexibility is required in the hips and knees, and some strength and control is required in the spine. How does one build these? Several positions, usually seated, were propagated in early hathayoga to help the body prepare for sitting or recover from the imbalances that arise during sitting. These postures include Cowface, Butterfly, Cobra, Bow and Locust. These are some of the first non-Lotus postures. 3. Anti-gravity postures. Influenced by tantra, hathayoga had many practices that were designed to prevent the precious bindu from dripping out of the head and into the abdominal fire. This was thought to improve vitality, spiritual potency and life. This is where we get the practices that turn the body upside down or "draw upward" the energy, winds or fluids of the body. Headstand, Shoulderstand, Mula Bandha, Uddiyana Bandha, and the upward-focused intention of many postures are intended for this purpose. 4. For physical health. These postures and exercises are much more recent, often coming from calisthenics, gymnastics and wrestling. They build strength, flexibility and health in the body. There are lots of different positions that affect varied parts of the body, so they are vast and diverse. Kuvalayananda called these "cultural" postures. These have become central to the practice of modern yoga. 5. For demonstration and impressive accomplishment. From ancient times, yogis have been associated with the ability to do remarkable feats. In the last couple hundred years, that has increasingly meant physical demonstrations of balance, endurance, strength and flexibility. Influenced by the developments of gymnastics, acrobatics and contortion, these practices include Splits, Handstand and most arm balances. This tendency toward outwardly impressive beauty has been compounded with the rise of photography, the internet and visual communication media like Instagram. Who doesn't love to see a beautiful, impressive picture of a body? One type of posture is not better than the others. There is no hierarchy here, though as yogis some danger lies in focusing on the body and in cultivating techniques for display. Worth noting is that postures can have drastically different purposes, goals and intentions. When we practice them, we should know what we are practicing so we can move in the right direction. Most yoga practitioners know pranayama is the skill and art of breath control. But the breath can be a difficult animal to tame.

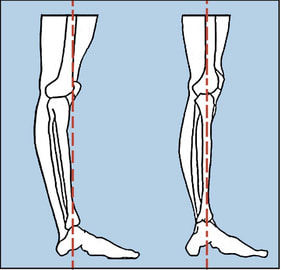

When we start to do breathing exercises, it can make us feel claustrophobic or anxious. Our breath is largely governed by the autonomic nervous system, and when we control it consciously we can run head-on into the body's habits and patterns. The Hathapradipika says, "like elephants and tigers, the breath must be controlled slowly." (II.15) When practicing pranayama, sit on the ground so that your legs are crossed and your torso is upright. Sit up nice and tall. If it's impossible to sit on the ground, you can sit in a chair. Make the body still so that the breath becomes the center of your focus. Always stay relaxed. If the breathing makes you anxious or panicky, stop immediately. Here are two simple and safe practices to start: 1) Even Counting, and 2) Alternate Nostril. EVEN COUNTING This technique is so simple that you may do it already in some yoga classes. It involves making the inhale and the exhale even in length. A great length to start with is 3 or 4 seconds each. So inhale for 3 or 4 seconds, then exhale for 3 or 4 seconds. Stay very relaxed and continue this for a few minutes. This technique has the effect of synchronizing the breath with the nervous system and the heart rate. After a minute or so you will feel quite calm, peaceful and centered. ALTERNATE NOSTRIL When starting with this technique there is no need to control or count your inhales and exhales. You can let the breath come in and out naturally and relaxed. Use your right thumb to close your right nostril. Inhale calmly through the left nostril. Then use the ring and pinky fingers to close the left nostril, open the right, and calmly exhale out of the right nostril. Then inhale through the right nostril. Then close the right nostril, open the left, and calmly exhale out of the left nostril. Continue in this fashion for about 5 minutes, staying as relaxed as you can. As mentioned above, controlling the breath can bring up anxiety or a sense of panic. If you feel this, stop immediately. The goal of these beginning breath practices is to stay absolutely calm throughout. They should give you a growing sense of well-being and peace, not anxiety. Once you can do these exercises with control, ease and calmness, you are ready to move on to more difficult practices. "Locking the knee" is a concept in yoga that was popular in the 60s and 70s, including the styles of BKS Iyengar and Bikram Choudhury. It originally comes from weightlifting, where full extension of the knee joint and concerted contraction of the quadriceps are paramount. You will still hear weightlifters talk about "locking out" to refer to the full straightening of a joint that is under stress.

For the most part, this concept has dwindled in the yoga world due to the confusion it causes. There are at least 3 different meanings to the phrase "lock the knee," depending on what position you are in and who you're talking to. An anatomist has a different definition than a Bikram Yoga teacher. These are the three meanings: 1. CONTRACT THE QUADRICEPS This is the original meaning of the term as it comes from weightlifting and bodybuilding. Used in quadricep-heavy exercises like squats, "lock the knee" meant to straighten the knee as much as possible by squeezing the quadriceps with great force. In the yoga world, this has also become a way to relax or stretch the hamstrings, since engaging the quads naturally causes the hamstrings to disengage. In addition, it is sometimes believed that engaging the quadriceps, which causes the kneecap to lift up, will protect the knee joint from hyperextension. (It won't.) 2. RESTING THE FEMUR ON THE TIBIAL SHELF Anatomically speaking, a normal knee has the ability to hyperextend by a few degrees. It can go past the 180 degrees of a straight leg by about 4-6 degrees. When we are standing and our legs are bearing weight, we have the ability to hyperextend the knees and "rest" them on the tibial shelf. They settle back and the muscles of the leg relax, allowing us to stand for long periods of time without using much energy. When the knees are resting in this manner, they are "locked." To unlock them, there is a specific muscle (the popliteus) that unlocks the knees before they return to normal function. This definition of a "locked knee," which is essentially slight hyperextension, is often conflated with the first: contracting the quadriceps. Unfortunately, the combination of hyperextension and contracted quadriceps will accentuate the knee's tendency to hyperextend and possible create instability. 3. ENGAGING ALL THE MUSCLES AROUND THE KNEE Normally, the contraction of the quadriceps is accompanied by a relaxation of the hamstrings, and vice versa. It allows for effortless movement of the knee back and forth. But this relationship can be overridden with conscious effort and control, contracting both sets of opposing muscles simultaneously. In yoga parlance this is called a bandha, a "lock." When opposing muscle groups around a joint are consciously contracted together, the joint does not move. On the contrary, it becomes immobile and quite stable. This is often done to create stability and pressure gradients that effect the blood and heat flow in the body. IN CONCLUSION As you can see, the phrase "lock the knee" can mean a handful of different things. And it is important to note that the interpretations can conflict with one another. The first involves engaging the quadriceps while relaxing the hamstrings; the second involves relaxing both the quadriceps and the hamstrings; and the third involves engaging both the quadriceps and the hamstrings. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed