|

Perhaps it is obvious to say that we should speak (and write) the truth.

Honesty is one of the fundamental principles of yoga, generally referred to using the word satya or truth. It is also fundamental to moral and spiritual traditions around the world and throughout history. Pick any tradition with a moral stance, and honesty or truth is probably in the top 10 rules. So it is hard to overstate the importance of avoiding lies, at almost all costs. DISSONANCE WITH REALITY The most significant reason to speak and think honestly is that it keeps us in harmony with reality. When we knowingly say false things, it pits us against the actual truth, which is a battle that we will not win, and it plays out in our psyche. For the most part, lying is an attempt at power. If I tell you an untrue version of events, you have little choice but to believe me. So, for a short while at least, I have exerted power over your perception of reality. The more elaborate I can make my lies, the more people I can convince and the more I feel that I am actually controlling what is real. This makes me feel powerful. The problem with this, aside from misleading others (which is usually remedied over time and through learning, as people gain new perspectives and information; the truth usually comes out), is that I have pitted myself against actual reality. I have fashioned myself as a creator of truth, which is not a natural role for a human, since we are far too small to control it. With every lie I tell, I separate myself from the way things actually are. I disconnect myself from reality. We have little choice in the matter: lies unhinge us, because they separate us from the truth. But the opposite is also true, which is why moral traditions take truth so seriously. The more I speak the truth and align myself with reality, the more I come into harmony with the way things are. So the world becomes clearer, people's thoughts, intentions and actions become clearer, and my own purpose becomes clearer. When I have made myself consonant with reality, much confusion and obscurity dissipates. WHAT IF I'M WRONG? None of us know everything, so it is inevitable that we will learn new information that proves our beliefs and statements wrong. There is no inherent dishonesty in being wrong. What is important is staying aligned with reality. So when our knowledge changes and we become aware of something new, often our beliefs must change to keep us truthful. It is far too easy and common for us to establish what we think of as "the truth," and then defend it against new information. This is called "confirmation bias," where we accept information that supports our currently-held worldview while rejecting anything that conflicts. This is admittedly part of our human psychology, but it amounts to telling ourselves little lies to maintain power over our construction of reality. In doing so, it separates us from actual reality.

0 Comments

Last week we asked you, our readers, for questions that you'd like addressed. We received many great inquiries, and today we will address one:

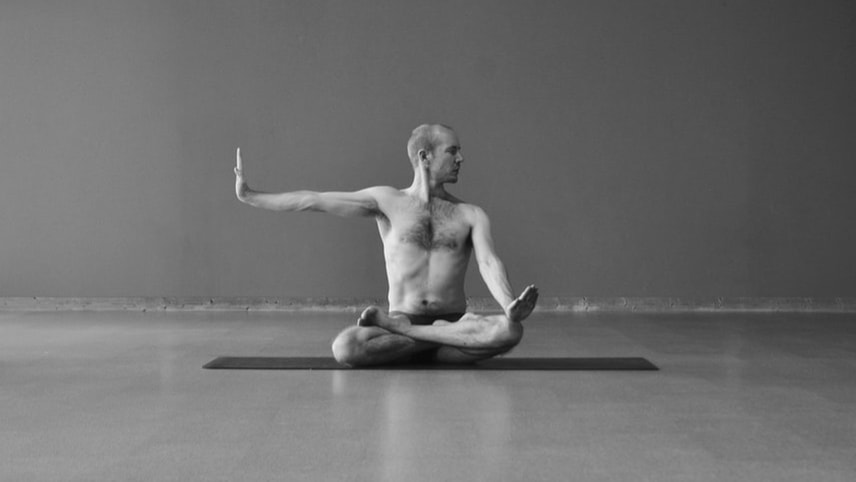

"Can you talk about the importance of stillness in yoga practice?" As we consider the importance or lack thereof of stillness, it is vital to consider the root question of any undertaking: what is the purpose? Before reading on, it is worth taking a moment to consider the purpose of your yoga practice. The form of your practice should serve its function, meaning that it should accomplish whatever it is that you are trying to achieve. This can be complicated when talking about yoga, because it has changed a lot over hundreds of years. TWO STYLES Stillness can be confusing and even controversial in today's Western yoga world. The majority of what is practiced as yoga today includes abundant movement, often referred to as "flow." Various bodily positions are fluidly linked together and transitioned between, with lots of Sun Salutes, a calisthenic exercise that incorporates regular breathing with stretching, a push-up-like movement and some spinal bending. The Sun Salute (Surya Namaskara) became popular in India in the 1920s. A contrasting style focuses on positions held in stillness, anywhere from 10 seconds to several minutes. In the past decade or so, it has become fashionable to refer to any stillness-based method as hatha yoga, presumably to separate it from the movement-based vinyasa methods described above. DIFFERENT YOGAS For the past hundred years or so, calisthenics, gymnastics, acrobatics and contortion have taken the name of yoga. This is why so much "yoga" in the West includes movement, strength, jumping, deep stretching, rhythmic breathing, getting the heart rate up, sweating, etc. Calisthenics and exercise have been known to improve physical and mental health, and it is no surprise that yoga practices have veered in this direction as our culture puts more and more value on fitness. But these tendencies--movement, health and fitness--are new to the yoga world. CLASSICAL YOGA The earliest extant texts on yoga, including the Upanishads, the Mahabharata and the Yoga Sutras, describe a practice of mental concentration, turning the senses, mind and intellect toward the inner self. This practice doesn't include moving the body in any particular position, other than holding it “steady like a pillar and motionless like a mountain. Then it can be said that they are practicing yoga.” (Mahabharata 12.294.15) According to these texts, stillness of the body is a prerequisite for yoga practice. If the body is moving, the senses are stimulated, including the sense of touch and sight to enable coordination and balance. The senses draw the mind outward, preventing it from turning inward in anything that could be called yoga practice. According to the earliest texts, yoga is not a physical practice but a mental one. So focusing on what we are doing with the body can be misleading, lest we think that holding the body in stillness equals practicing yoga. But the body must be held "as motionless as a rock” (Mahabharata 12.294.14) for the true practices of yoga--the mental elements--to be done. WHAT ARE YOU PRACTICING? Over the past 100 years or so, increasingly physical activities have been labeled "yoga," bringing us to the present day, when yoga has the connotation of gentle exercise, stretching and perhaps some spiritual elements. The physical focus has become more central, and the mental/spiritual focus has diminished greatly. If you want to improve your flexibility and reduce your stress, the low-impact exercises that are now known as yoga will be helpful. If you want to increase your cardiovascular endurance, you should do longer, more repetitive exercise like running or swimming. Even the most vigorous yoga practices only give a fraction of the cardiovascular benefit of running. If you want to lose weight, check what and when you are eating, your stress and sleep. If you want to understand the nature of your mind, being and who you are, the meditative practices of yoga are for you. In the end, it doesn't much matter what you call the practices, it just matters what the practices accomplish. So whether you call it yoga or something else, try to choose the right practices for your goals. The ultimate goal of yoga practice is understanding the true nature of who we are. This can seem abstract--how could we possibly be anything other that who we are?--but it has to do with the ego and the mind's creation of an identity. To realize our true self we strip away the mental constructions and are left only with our deepest "self."

The first step in this process is the body, since we identity our "self" with the body and its actions. So we teach ourselves that our body and its actions are malleable and impermanent. Since they are being controlled by a deeper power, they cannot possibly be the truest form of the self. We do this by controlling the body with yoga postures and alternating with stillness. This alternation between effort and rest, action and non-action, the posture and not the posture, gradually teaches us that even when we are not doing anything we are still ourselves. Again, this may seem obvious or abstract, but you may be surprised how hard it is to do nothing. Our minds and bodies are constantly drawn toward action, as if their very existence relied upon it. When we force the body to be completely still we can face something of an existential crisis, fearing that we will cease to exist of we cease to act. This is why alternating action and inaction--the posture and not the posture--is so profound. Two of the most important ideas in yoga philosophy are "ignorance" (avidya) and "discernment" (viveka). They are opposite sides of the same coin. When we develop discernment our ignorance is eradicated.

Ignorance (avidya) is sometimes called "primordial ignorance" since it is the state into which we are all born. It is like original sin in that way. It is the way we associate our thoughts and emotions with our deepest self. We notice thoughts and think, "This is me." "I am nervous." "I am angry." "I am confused." We develop a sense self, often called I-ness, ego or asmita. But these thoughts are not the essence of our being, and when we think that they are, it is ignorance. Discernment (viveka) is also called "discrimination" and "knowledge." It is one of the highest goals of yoga, as we realize the true nature of ourself. As we observe our thoughts and emotions, we come to realize that they are not the deepest part of us. There is something deeper since it is observing the thoughts and emotions. So we search for the nature of this "observer," also called "the seer" or simply "consciousness." The transition from ignorance to discernment is subtle, complex and takes many years. But it begins very simply. We notice our thoughts and emotions. That is the first step! When we recognize violence and suffering in the world, often our first response is, "How can I help?" What can I do to reduce the violence, to reduce the suffering?

It is easy to say that the world needs to change, or to try to affect change in the world. The problem with this attitude, from a yogic perspective, is that it externalizes. It has us imposing our will upon the world, usually at the expense of a clear view of ourselves. It is generally our most ingrained and obvious views that we seek to export to others. In the Yogasutras it is explained that, "When non-violence (ahimsa) is firmly established, hostility vanishes in the yogi's presence." (2.35) Only when we are peaceful ourselves can we affect peaceful change in the world. As one of our teachers said, "It is impossible to give what you don't have." If we are not peaceful, how can we give peace? It is as futile an effort as if we had no food but tried to give food to others. First we must have something before we can offer it. So, from the yogic view, the best way to reduce someone else's suffering is to eliminate our own. The best way to bring peace is to become firmly established in peace ourselves. Whenever we teach yoga, it is mostly done with words. We describe the actions, body movements, breathing, areas of concentration and purpose to our students. Sometimes there are moments of demonstration, discussion, contemplation and quiet practice, but for the most part yoga teaching is done by speaking. This makes our words important. What are we saying? And for what purpose?

OLD WORDS There is value in repeating the words of our teachers. It can root us in tradition, since our teachers often learned the same words from their teachers. It can also bring us closer to our own past experiences of practice, since we heard our teachers use the words while we were discovering. Now those same words can tether us to our own practice even as we guide others. Sometimes the words of our teachers are simply great, and try as we might, we can not invent a more effective way to describe a concept or action. In these cases, repeating our teachers is a wise choice. But there is also danger in repeating someone else's words, even when they come from a knowledgable, respectable source. The greatest risk is that we will instruct what we do not understand ourselves. When we already have instructions ready to disperse, there is little motivation to plumb the depths of practice and then teach from our own knowledge. We may end up teaching things far beyond our own ability and understanding, and this is bad for everyone--us, the students and the knowledge that we are claiming to perpetuate. Another danger is that speaking someone else's words can disconnect us from our own knowledge and experience. It is easy to switch to autopilot when we have the words ready beforehand. We can disconnect from our own practice as well as the needs of the students in front of us, simply repeating prepared statements that may or may not apply to the current moment. NEW WORDS Sometimes we invent our own instructions to guide our students. This has the advantage of being absolutely real and true; we aren't instructing what we've heard or read but what we've practiced and experienced. Almost always these words are clear, evocative and precise. When we speak with our own words, we are forced to connect our brains (and mouths) to our own knowledge, and this brings unity to both our teaching and practice. Disparate parts become unified. Also, this forces us to teach what we know. When we use our own words, there is no possible way to instruct something beyond our own understanding. The greatest danger to teaching in the moment with our own words is that we can lose humility and become caught up in our own story. We get intoxicated with the sound of our own voice, convinced that our experience is worth trumpeting, that our instructions are worth following. This perspective is ruinous to the yogi, as the ego can grow and drown out all yogic knowledge and humility. IN CONCLUSION There are pros and cons to repeating traditional words, old phrases and the words of our teachers. The same is true for inventing our own instructions directly from personal experience. Above all, we must be aware of what we say and why, and also what impact the words have on our students and us. I recently added fasting to my yoga practice. For one day each week I don't eat. It's not for losing weight, to look different or even for health purposes of any sort. I am fasting to clarify my relationship between my body and mind and to understand how what I eat affects both.

In yogic teachings, the practice of fasting can be associated with pranayama (energy control) and pratyahara (sensory control). Pranayama is most often connected with breathing since it is such an elemental part of our existence. (I wouldn't live long if I stopped breathing.) Eating too is a deeply-rooted part of my physical existence, so its pull on my consciousness is strong. As pranayama practice develops, it naturally evolves from the breath toward eating and other "essential" life-functions. Fasting is also part of pratyahara, the practice of looking at my sensory input and how it affects the way I perceive the world (and myself). My sense of taste is obviously related to food, and our culture has increasingly turned toward foods that stimulate my taste receptors, so much that I often consume food for the way it stimulates my mouth (and brain). When I control my food intake, I quickly come face to face with the powerful connections between my senses (in this case, taste) and my reality. Controlling the energy and senses is hard, so fasting is hard. Quite literally it challenges my constructed perceptions of who I am. This is why dieting and food control is often a lost cause. The yogis consider fasting a relatively advanced form of control, so it makes sense when so many people struggle with it. Over the past two months, we have uprooted our lives, moving out of a house that's been in my family for decades and into a small apartment that will enable us to be more mobile. Throughout the process I have been reminded of 3 disparate teachings from 3 different sources that all point to the same idea: that a yogi becomes invisible.

We often talk about "drawing toward" and "pushing away," so much that it was even the topic of a blog last year. When we are compelled to draw things toward us, whether they are objects, money or the attention of others, we fortify the constructs of our personality and take ourselves further from liberation (the essential, non-constructed version of the self). These things make us bigger, sometimes literally and sometimes theoretically. As we remove these constructs, the yogi becomes "smaller" until she approaches invisibility. Looking back into history, the yogasutras state that suffering comes from pairs of opposites (2:48), including hot and cold, good and bad, etc. When we adhere to the pairs of opposites, swinging from happy to sad and back again, we are like a tight-rope walker who is wobbling violently from side to side. As we reduce our movement from side to side, we approach stillness in the middle, which from the outside can seem like nothing is happening. But the stillness reveals deeper movement that was imperceptible when the action was bigger. The more centered the yogi becomes, the more still she is. She approaches invisibility through her lack of drastic shifts. Most literally, this was said to us by Tony Sanchez, one of our teachers. During our time with him, he told us that "a yogi becomes transparent, almost invisible." This is contrary to our culture, in which we become more visible and famous as success increases. The yogi, on the other hand, does not pursue worldly gain or the admiration of others. Quite the opposite. As the yogi progresses, she has less and is attached to less. So I ask you: Do you draw things toward yourself? Do you embrace the pairs of opposites? Do you pursue the admiration of others? Do you make yourself still? Are you invisible? It may seem like a simple and obvious question: what are we really teaching? But if we look a little deeper, we may find that our intentions can conflict with what we are teaching our students.

The simplest answer to this question for modern Western yogis is: asana, postures. We teach physical practices for the health benefits of mobility and flexibility, strength, balance and inversion. We also teach breathing, which can slow the heart rate, lower the blood pressure and reduce stress. The physical, mental and nervous system benefits of yoga practice are real, and they are increasingly central to the yoga culture. This only creates an ideological conflict when we claim to be teaching anything like traditional yoga. The systems of yoga are many, but prior to a few hundred years ago most were dedicated to the subordination of the body and senses in favor of the realization of the true nature of the self. Do you see the conflict between these two ideas? When we practice modern physical yoga, it is often alongside confidence-building rhetoric that values personal experience. "Have faith in yourself," "You are your own best teacher," we may tell our students. These things build our identification with our bodies and the physical practices, working against the progress of dis-identifying with the body. So, in a traditional sense, a physically-focused practice centered on accomplishing postures, and even health, can work against the ideals of yoga. Admittedly, this is complicated. We are not suggesting that you change the way you teach or the way you approach your practice. But it is worth noting some of the little conflicts and paradoxes that arise in our yoga. These conflicts shed light on our assumptions and allow us to refine our view of ourselves and the world. As we deepen our practice and study of yoga, the sheer volume of practices and traditions can be overwhelming. One solution is to stick to the teachings of one tradition and explore them deeply. Even so, I am often curious about why different traditions may have such disparate teachings, all called yoga.

Looking back in history can help clarify the purpose of many practices. We were recently asked if there was ever a point when all yoga was unified around a single set of teachings. Not to my knowledge, unless we go all the way back to the first documented explanation of yoga in the Katha Upanishad, from about 2,500 years ago: "When the five senses are stilled, when the mind Is stilled, when the intellect is stilled, That is called the highest state by the wise. They say yoga is this complete stillness In which one enters the unitive state, Never to become separate again. If one is not established in this state, The sense of unity will come and go." No mention of postures, health, nutrition, stress or flexibility. Only the senses, the mind, the intellect, and a unitive state that arises when they are still. The Katha Upanishad, Part 2, Chapter 2, Verse 10-11. (This post originally published 2/9/2017) |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed