|

There is a lot of discussion and disagreement about the question: Is yoga a religion?

Many answer by saying yoga is "spiritual" but not "religious." There continue to be cultural movements to secularize yoga by taking away any direct mentions of worship or deities. And there are even combinations of yoga with non-Hindu religions, as old as the Allah Upanishad and as new as Christian Yoga. Let's take a look at the meaning of these words: spiritual and religious. And also at some history of yoga teachings and texts to see if we can find clues. WHAT IS RELIGION? Webster dictionary defines religion as "the service and worship of God or the supernatural." That is pretty broad, but it specifies that a system is religious when it acknowledges a God figure or some supernatural force worthy of worship. The word spiritual is defined as "of, relating to, consisting of, or affecting the spirit." Other definitions include "relating to sacred matters," which has a distinctly religious overtone. Another definition comes right out and makes the connection, saying spiritual means "concerned with religious values." Already for me the distinction between religious and spiritual seems like a stretch, like perhaps we are trying to make a distinction where none really exists. YOGA How does yoga fit into these definitions? Do the teachings of yoga recognize a God or supernatural being/force? Does yoga affect the spirit? For answers to these questions, I looked at two pivotal texts of yoga: The Yogasutras by Patanjali and the Yoga Yajnavalkya. The former is well-known. The latter is one of the most quoted texts by later yoga works. YOGASUTRAS The very beginning of the Yogasutras defines yoga as the "cessation of the turnings of thought." (1) No mention here of any god or supernatural power. No mention of the spirit either. According to this definition, yoga is a mental process having to do with our thought processes. The next verse complicates things a little. "When thought ceases, the spirit stands in its true identity as observer of the world." (2) Here we have the blatant use of "spirit," and we are thrown into the whirlwind of trying to understand and explain what that may be. But there is still no direct mention of a higher power. A few verses later we learn about Ishvara, the Lord of Yoga. "Cessation of thought may also come from dedication to the Lord of Yoga. The Lord of Yoga is a distinct form of spirit unaffected by the forces of corruption, by actions, by the fruits of action, or by subliminal intentions. In the Lord of Yoga is the incomparable seed of omniscience. Being unconditioned by time, he is the teacher of even the ancient teachers." (3) This passage directly refers to an omniscient supernatural being who is unaffected by time. It certainly falls under the definition of religion by encouraging the 'service and worship,' or as the Yogasutras put it---'dedication'---to a god figure. YOGA YAJNAVALKYA This text is the origin of the oft-repeated definition of yoga: "Yoga is...the union of the individual self and the supreme self." (4) Here we have the ambiguous notion of the "supreme self." Is it a figment of our imagination, the best version of ourselves, or a supernatural entity of which our human self is part? This definition often gets relayed as "union of the individual self with the universal self," which has a lot more supernatural meaning in it: We are all one. To me, this definition wobbles on the edge of religion, depending on how you choose to interpret the "supreme/universal self" and whether you consider that to be a supernatural entity. Some of the gray area is clarified if we look earlier in the text to some of the first verses. "...Meditating in his heart with one-pointed concentration upon Narayana (the Divine), the refuge of the universe, residing in the heard of all beings in all worlds, the source of this universe, worthy to be meditated upon by yogis, unattached, blissful, immortal, eternal, omnipresent, and the ruler of the senses..." (5) Here we have distinct reference to "the divine," a supernatural being who is the "source of the universe." While worship is not specifically instructed, we are advised that this "immortal, omnipresent" divine is "worthy to be meditated upon." To me, this is quintessential religion. IN CONCLUSION Depending on where we look and how narrow our gaze is, we can convince ourselves that yoga is not a worship-centric religion that looks to a supernatural being. But as our view starts to expand even within the same texts, there are definite religious elements: Timeless, omniscient beings who are the source of the universe. So, is yoga a religion? In a word, yes. 1. Patanjali, Yogasutras, 1.2 2. Patanjali, Yogasutras, 1.3 3. Patanjali, Yogasutras, 1.23-26 4. Yoga Yajnavalkya, chapter 1, verses 43-45 5. Yoga Yajnavalkya, chapter 1, verses 9-19

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

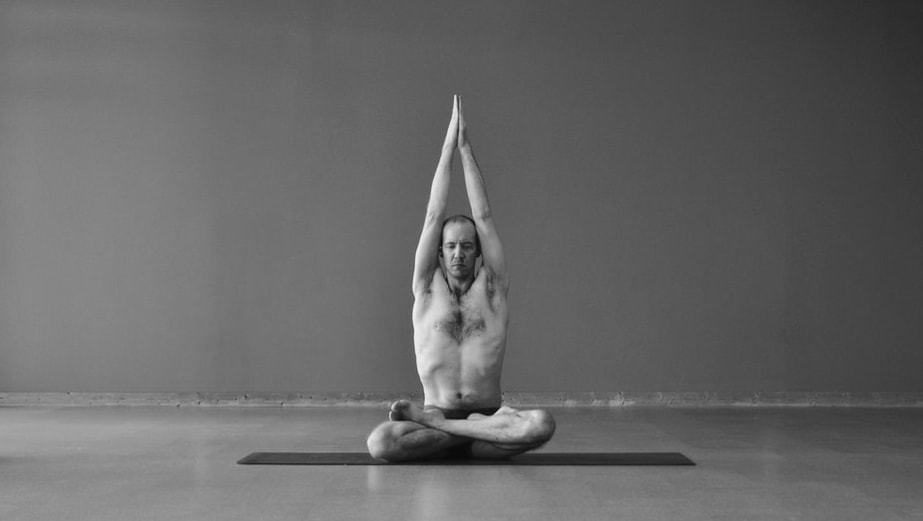

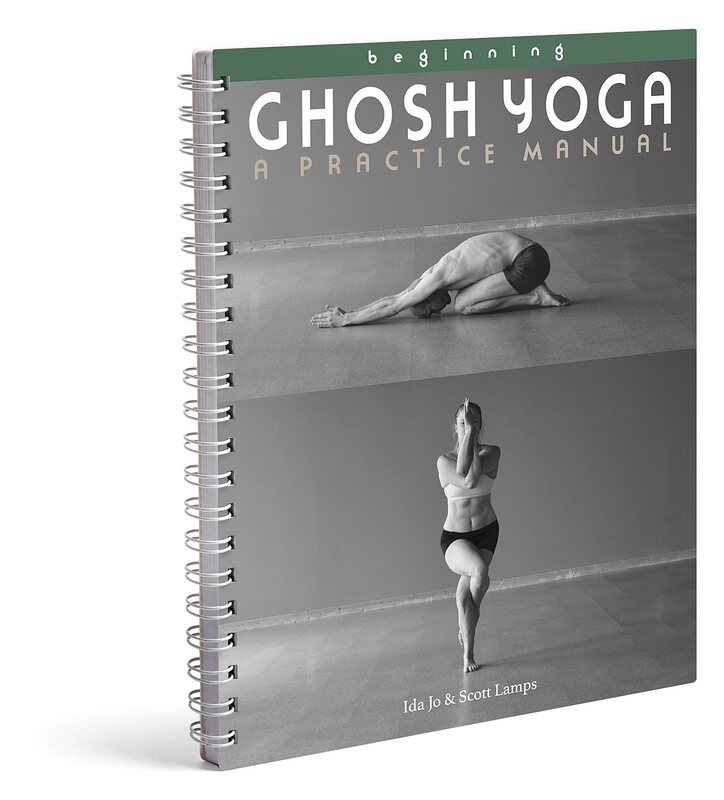

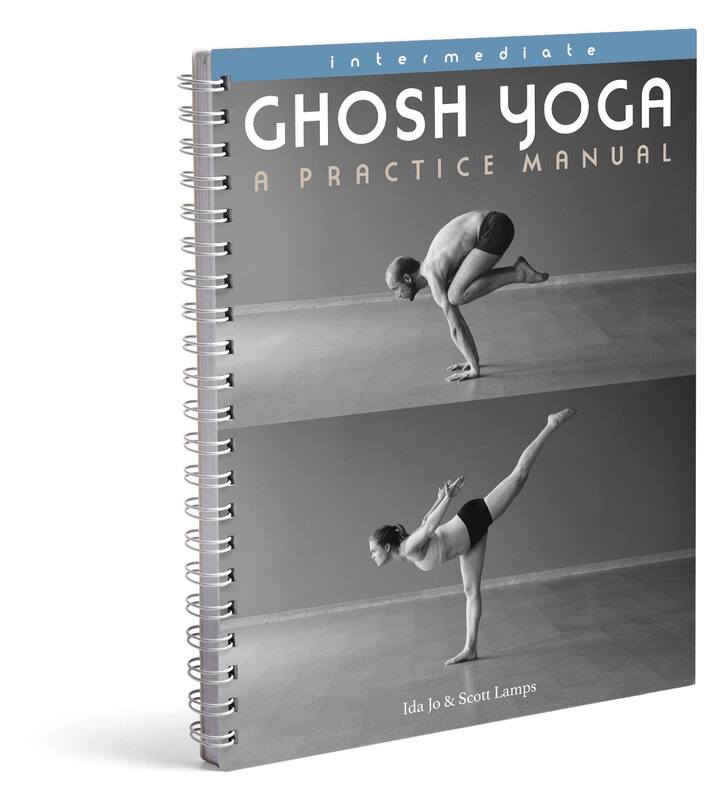

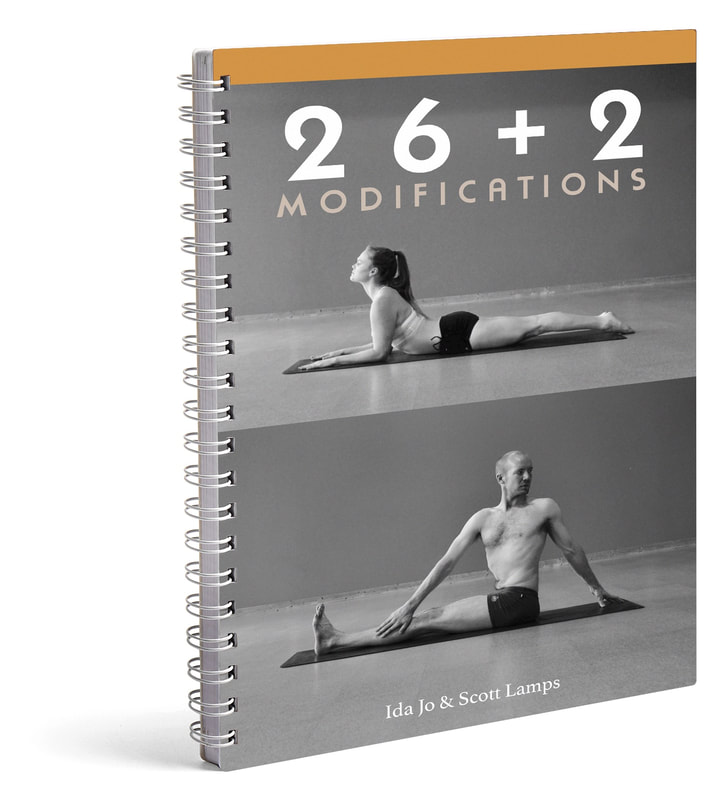

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed