|

It is Practice Week this week, and we are in Pennsylvania. The days are intense and draining: 5 hours of practice and another 3 hours of discussion. It is an all-out extravaganza for the body and mind. Needless to say, the end of the day finds us exhausted, and it only compounds over the course of the week.

But I have always been a morning person, and no matter how tired I am, I usually wake up early. I say this with no sense of pride; I would often choose to sleep later if I could. But once my internal clock decides it’s time to wake up, there is no way of returning to rest. So I get up. My favorite thing to do in the morning, aside from doing breathing practices, is organize information. It is so quiet and peaceful, and my mind is full of new connections that were generated while I slept. I love to write down little bits of information that I’ve learned and questions I have. I read and research to find answers to my questions. Sometimes I gain a new sense of understanding. This morning, I sat in the yoga room here in Pennsylvania before anyone else was up. I gathered pictures and bits of info and placed them into a slide presentation. I rearranged their order until a coherent story appeared. I looked up, saw myself in the mirror and realized that this is a pattern with me: rise early and organize information.

0 Comments

When we step in front of a class of students to teach, it is natural for the ego to grow. After all, the teacher is one person while the class is many people. The teacher knows about the practices, history and purpose while the class is learning. The teacher controls the practice while the students follow her lead. All attention is directed toward the teacher. It is normal for this to create an inflated sense of importance. But the teacher and student are two parts of a larger system of learning, and they need to work together to be successful. As much as the student must serve the teacher to learn and progress, the teacher must also serve the student. The two are an inextricable team. In the Sivananda tradition, there is a little invocation that precedes every class, describing this union between the teacher and student, and how they must work together in harmony. May we (the teacher and the student) be protected together, May we be nourished together, May we both work together with great energy, May our study be enlightening and not give rise to hostility. ...AND NOT GIVE RISE TO HOSTILITY

I especially like the last line: "May our study be enlightening and not give rise to hostility." It is pretty easy for the teacher to resent students who do not listen to instruction. These students make the teacher feel powerless and worthless, so the teacher dislikes them. Hostility is born. It is also easy for the student to resent the teacher. The student may be struggling to understand or progress. Or he may have conflicting experience or knowledge that makes him resist the new teachings. Or he may just be having a bad day. As the teacher pushes the student to conform, the student grows frustrated with the teacher. More hostility is born. BETTER COMMUNICATION It is important not only to avoid this hostility, but to actively promote collaboration and communication between teacher and student. We are all in it together. It is a symbiotic relationship, as the student can not exist without the teacher and the teacher can not exist without the student. A student must always be able to ask questions. Surprisingly, the questions will help the teacher as much as the student. They reveal the student's understanding--where he gets it and where he struggles. This is the single greatest tool that a teacher can use to serve her students. We begin at the beginning. That much is obvious.

As we practice, we gain proficiency; we get good at whatever we are drilling. Soon enough, it becomes time to move on and up to the next level. Almost all disciplines take this process for granted. If you study music, you start with the Level 1 book and move through Level 2 up as high as you can, through maybe 6 to 10 levels. And that is all before you even arrive at the University level that plays the standard "repertoire" that makes up most concerts. Even school subjects progress through levels, building on one another to create complex and deep understanding. Arithmetic is layered with geometry, algebra and calculus to give the student a high level of competency in maths. Sadly, this structure rarely exists in yoga, especially in the West. The studio culture that has built up---where we attend a group yoga class in the morning or after work---contains almost exclusively "all-levels" classes, which means that they aren't particularly suited for beginners or experienced practitioners. Since we all begin at the beginning, we should do the simplest introductory practices. We are in Yoga First Grade, learning the yogic equivalent of counting and the alphabet. This includes things like touching our toes, awareness of the breath and perhaps even linking our breath with movement. Before too long we graduate to Yoga Second Grade, where we build upon the skills we have learned. This continues indefinitely as the practices become more and more complex. This may seem obvious, but it is quite common in the yoga world for beginners and experienced practitioners to do the same practices, the equivalent of having everyone in the room practice algebra even though some don't know how to add while others are astrophysicists. Who is being served? Practice must begin simply and it must evolve. It must grow and increase in complexity. As teachers, we must embrace and enable these qualities and capabilities in our students. Whenever we teach yoga, it is mostly done with words. We describe the actions, body movements, breathing, areas of concentration and purpose to our students. Sometimes there are moments of demonstration, discussion, contemplation and quiet practice, but for the most part yoga teaching is done by speaking. This makes our words important. What are we saying? And for what purpose?

OLD WORDS There is value in repeating the words of our teachers. It can root us in tradition, since our teachers often learned the same words from their teachers. It can also bring us closer to our own past experiences of practice, since we heard our teachers use the words while we were discovering. Now those same words can tether us to our own practice even as we guide others. Sometimes the words of our teachers are simply great, and try as we might, we can not invent a more effective way to describe a concept or action. In these cases, repeating our teachers is a wise choice. But there is also danger in repeating someone else's words, even when they come from a knowledgable, respectable source. The greatest risk is that we will instruct what we do not understand ourselves. When we already have instructions ready to disperse, there is little motivation to plumb the depths of practice and then teach from our own knowledge. We may end up teaching things far beyond our own ability and understanding, and this is bad for everyone--us, the students and the knowledge that we are claiming to perpetuate. Another danger is that speaking someone else's words can disconnect us from our own knowledge and experience. It is easy to switch to autopilot when we have the words ready beforehand. We can disconnect from our own practice as well as the needs of the students in front of us, simply repeating prepared statements that may or may not apply to the current moment. NEW WORDS Sometimes we invent our own instructions to guide our students. This has the advantage of being absolutely real and true; we aren't instructing what we've heard or read but what we've practiced and experienced. Almost always these words are clear, evocative and precise. When we speak with our own words, we are forced to connect our brains (and mouths) to our own knowledge, and this brings unity to both our teaching and practice. Disparate parts become unified. Also, this forces us to teach what we know. When we use our own words, there is no possible way to instruct something beyond our own understanding. The greatest danger to teaching in the moment with our own words is that we can lose humility and become caught up in our own story. We get intoxicated with the sound of our own voice, convinced that our experience is worth trumpeting, that our instructions are worth following. This perspective is ruinous to the yogi, as the ego can grow and drown out all yogic knowledge and humility. IN CONCLUSION There are pros and cons to repeating traditional words, old phrases and the words of our teachers. The same is true for inventing our own instructions directly from personal experience. Above all, we must be aware of what we say and why, and also what impact the words have on our students and us. Last week we announced a 4-week program for training yoga teachers, and along with it a program for more advanced students and teachers called the "Ghosh Yoga Mentorship Program." In the ensuing days, we received many questions about the program: What is it? What does it entail?

To talk about what the "Mentorship Program" is, we have to go all the way back to the beginning, to the nature of knowledge, experience, and the best way to pass them on through something like a "training." You see, we think that the Western systems of teaching are limited. With so much structure and focus on classroom logistics, we Westerners have maximized efficiency while sacrificing individuality and subtlety. This may be suitable for the rudiments of a subject, like beginning classes in math, science and even yoga, but once a student grows past the early stages, she must be shepherded by a thoughtful and individual teacher. Only with personal attention and instruction can a student make real progress and find her own identity, passion and vision. So we are adopting a method of teaching that is closer to the way yoga has been passed down traditionally, with individual attention and consideration. With the goals of yoga in mind, each student will be assigned slightly different variations of the physical practices, based on their ability; different breathing practices, based on their experience; different sensory and mental practices based on their awareness and understanding; different historical and theoretical readings based on disposition and desire; and different teaching techniques based on skill, alertness and experience. It is difficult to answer questions about "what does the mentorship entail?" because it will entail something different for each student. One student may focus on studying sutras and retaining the breath, while another may focus on strengthening her feet, balancing the nervous system and speaking loudly. We hope that any confusion this causes up front while people are trying to understand if this program is "right for them" will be balanced out by the unmatched quality and specificity of the mentorship. As always, please ask us if you have any questions! There is a fine line between teaching someone and insulting them.

It is no surprise that being a teacher involves telling people things that they don't know. This can range from a simple addition of new knowledge - by far the easiest for the student to integrate - to the shifting of concept or understanding, which is much harder for any student to do. Anytime we have to reorganize our belief system or reconfigure how we look at a problem, it requires significant effort and faith from us. This is largely due to our "confirmation bias," a mental phenomenon which causes all of us to adopt beliefs that confirm what we already think and ignore anything that conflicts. As teachers, we always have to tread lightly when correcting people, since they are doing the best they can, using every ounce of their intelligence to be all they can be. When we step in and tell them that they are doing something wrong, we can unknowingly tread on deep-held beliefs and long-held habits. Every time we correct a student, we are basically telling them they are wrong, which no one likes to hear. We can put our students on the defensive through the simple act of trying to help them. For the student, it is rarely as simple as just changing what they do and how they think, which is why students often adjust to our instruction in the moment and then go right back to doing what they were doing. In these instances, we have not made any progress in instructing the student, since they have not made any progress in their understanding. The way around this is not to avoid correcting our students, but to approach them like we are on their team instead of a superior who is "fixing" them. We must keep in mind that they are doing what they think is right. If they knew they were doing something wrong, they would change it immediately. We are not "correcting" them, but giving them an opportunity to improve. And who doesn't readily accept an opportunity to improve? It may seem like a simple and obvious question: what are we really teaching? But if we look a little deeper, we may find that our intentions can conflict with what we are teaching our students.

The simplest answer to this question for modern Western yogis is: asana, postures. We teach physical practices for the health benefits of mobility and flexibility, strength, balance and inversion. We also teach breathing, which can slow the heart rate, lower the blood pressure and reduce stress. The physical, mental and nervous system benefits of yoga practice are real, and they are increasingly central to the yoga culture. This only creates an ideological conflict when we claim to be teaching anything like traditional yoga. The systems of yoga are many, but prior to a few hundred years ago most were dedicated to the subordination of the body and senses in favor of the realization of the true nature of the self. Do you see the conflict between these two ideas? When we practice modern physical yoga, it is often alongside confidence-building rhetoric that values personal experience. "Have faith in yourself," "You are your own best teacher," we may tell our students. These things build our identification with our bodies and the physical practices, working against the progress of dis-identifying with the body. So, in a traditional sense, a physically-focused practice centered on accomplishing postures, and even health, can work against the ideals of yoga. Admittedly, this is complicated. We are not suggesting that you change the way you teach or the way you approach your practice. But it is worth noting some of the little conflicts and paradoxes that arise in our yoga. These conflicts shed light on our assumptions and allow us to refine our view of ourselves and the world.

Yoga classes are filled with students of different skill levels. The majority of students are somewhere in the middle: familiar with the practices, having attended dozens or hundreds of classes, neither beginning nor advanced. Some are new, never having done yoga before, and a few are more advanced, having practiced for long enough to move past beginning techniques. As teachers, how do we navigate this diversity?

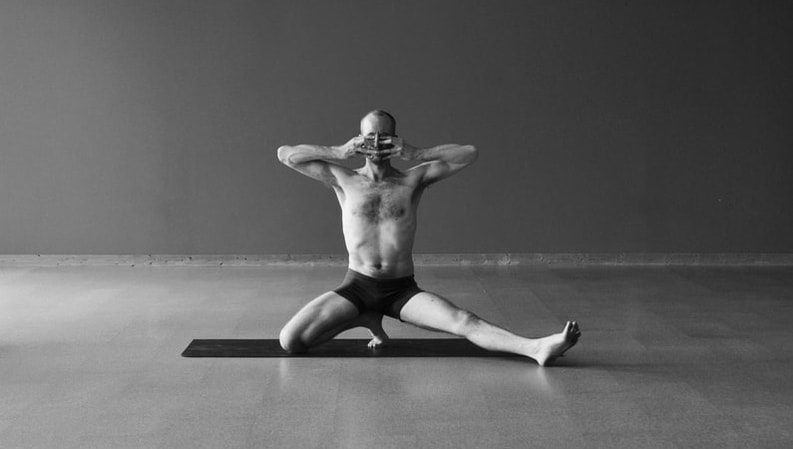

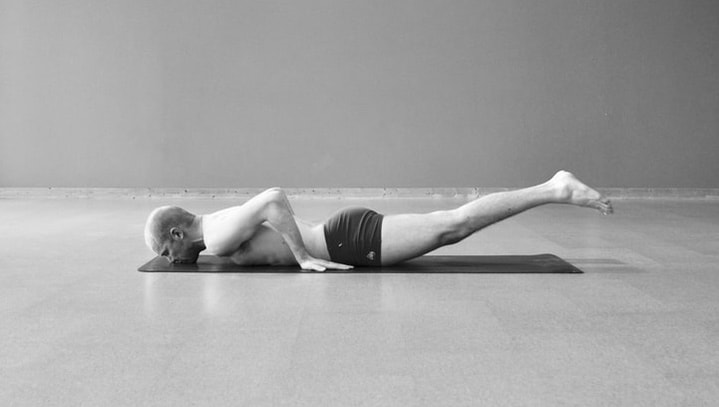

BEGINNING AND ALL-LEVELS CLASSES One of the solutions that the yoga community has developed is "Beginning Class" or "All-Levels Class." These classes are attractive to newcomers since the practices aren't too difficult, and tentative new students won't be distracted or discouraged by confident, flexible yogis on the mat next door. A beginning class is targeted toward beginners. "All-levels" is a descriptor that basically means "beginning," but it tries to avoid alienating more experienced yogis the way that a term like "beginning" might. The obvious complements to "Beginning" class are "Intermediate" and "Advanced" classes. But there aren't nearly as many intermediate or advanced students, so these classes are unsustainable to a yoga studio. Non-beginning classes generally get limited to once or twice per week or dropped altogether, while beginning classes fill the rest of the schedule. So it is difficult for intermediate and advanced yogis to find classes or spaces to practice at their level. What we end up with is more advanced students in "beginning" classes. It is the teacher's responsibility to direct the students in his or her class, whoever those students may be. A teacher needs to be able to guide a beginning student in appropriate beginning practices, and also guide an advanced student in appropriate advanced practices. This requires some knowledge and skill from the teacher, who needs familiarity with beginning postures, modifications and injuries as well as intermediate and advanced postures and variations. Too often, teachers hold back their advanced students, demanding that they do beginning postures that will not benefit them, or worse, encouraging them to do beginning postures but work harder. This is the most common way to injury. THEIR OWN PRACTICE We often hear yogis make the case that beginning students should embrace "their own practice," meaning that they shouldn't be ashamed if they struggle or look silly. This helps the student trust the process. But the same is true for the advanced student who needs to embrace "their own practice." Too many advanced yogis hold back their practice for the sake of someone else in the room. Ideally, a yoga teacher can direct students of all levels at once. The beginner gets simple instruction while the experienced practitioner gets more detail and depth. All parties should respect their own place and the place of their peers. As a teacher, there are few skills more useful than the ability to modify postures to fit the needs of an individual student. In sheer value it rivals the ability to lead a class, but modification requires significantly more knowledge and patience. After all, each classroom is filled with individuals who have different strengths, weaknesses and injuries.

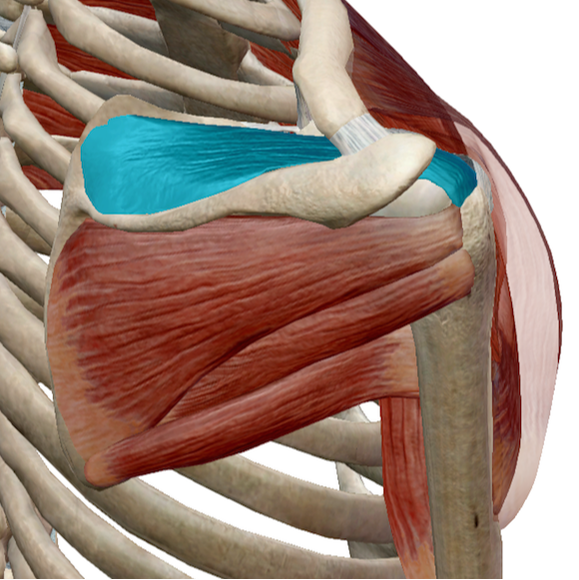

THE PURPOSE OF THE POSTURE Modifying any yoga posture or practice requires two things. The first is knowledge of the posture: What is its purpose? What are we trying to accomplish through its practice? Second is understanding how to adjust a posture to bypass a student's injuries and limitations while maintaining its primary function. Each posture is nothing more than the sum total of its benefits. Does it build strength, flexibility, massage the intestines, affect the blood pressure, etc? Each posture has a unique combination of benefits that defines its purpose. To know these benefits is to understand the posture. Of course, some benefits are more important than others. In general, benefits to the spine, torso, abdomen and circulatory system are more important than the extremities like the arms and legs. Coincidentally, many of the limitations that yoga students have are in their extremities: knee replacements, tight shoulders, painful feet, shaky balance. This means that we can often improve a student's ability to execute (and therefore obtain the benefits of) a posture by removing the extremities and focusing on the center. |

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed