|

"Locking the knee" is a concept in yoga that was popular in the 60s and 70s, including the styles of BKS Iyengar and Bikram Choudhury. It originally comes from weightlifting, where full extension of the knee joint and concerted contraction of the quadriceps are paramount. You will still hear weightlifters talk about "locking out" to refer to the full straightening of a joint that is under stress.

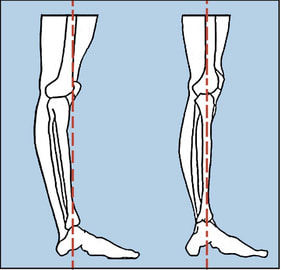

For the most part, this concept has dwindled in the yoga world due to the confusion it causes. There are at least 3 different meanings to the phrase "lock the knee," depending on what position you are in and who you're talking to. An anatomist has a different definition than a Bikram Yoga teacher. These are the three meanings: 1. CONTRACT THE QUADRICEPS This is the original meaning of the term as it comes from weightlifting and bodybuilding. Used in quadricep-heavy exercises like squats, "lock the knee" meant to straighten the knee as much as possible by squeezing the quadriceps with great force. In the yoga world, this has also become a way to relax or stretch the hamstrings, since engaging the quads naturally causes the hamstrings to disengage. In addition, it is sometimes believed that engaging the quadriceps, which causes the kneecap to lift up, will protect the knee joint from hyperextension. (It won't.) 2. RESTING THE FEMUR ON THE TIBIAL SHELF Anatomically speaking, a normal knee has the ability to hyperextend by a few degrees. It can go past the 180 degrees of a straight leg by about 4-6 degrees. When we are standing and our legs are bearing weight, we have the ability to hyperextend the knees and "rest" them on the tibial shelf. They settle back and the muscles of the leg relax, allowing us to stand for long periods of time without using much energy. When the knees are resting in this manner, they are "locked." To unlock them, there is a specific muscle (the popliteus) that unlocks the knees before they return to normal function. This definition of a "locked knee," which is essentially slight hyperextension, is often conflated with the first: contracting the quadriceps. Unfortunately, the combination of hyperextension and contracted quadriceps will accentuate the knee's tendency to hyperextend and possible create instability. 3. ENGAGING ALL THE MUSCLES AROUND THE KNEE Normally, the contraction of the quadriceps is accompanied by a relaxation of the hamstrings, and vice versa. It allows for effortless movement of the knee back and forth. But this relationship can be overridden with conscious effort and control, contracting both sets of opposing muscles simultaneously. In yoga parlance this is called a bandha, a "lock." When opposing muscle groups around a joint are consciously contracted together, the joint does not move. On the contrary, it becomes immobile and quite stable. This is often done to create stability and pressure gradients that effect the blood and heat flow in the body. IN CONCLUSION As you can see, the phrase "lock the knee" can mean a handful of different things. And it is important to note that the interpretations can conflict with one another. The first involves engaging the quadriceps while relaxing the hamstrings; the second involves relaxing both the quadriceps and the hamstrings; and the third involves engaging both the quadriceps and the hamstrings.

6 Comments

Alice Nelson

6/11/2019 04:51:39 am

Such a great explanation on this topic. Thank you as always for the insight.

Reply

Jessica

6/11/2019 08:37:29 am

This is an awesome share! For the Bikram series, what do you recommend for postures that involve "locking the knee?" Do you want all of the muscles around the knee to be engaged?

Reply

Scott

6/12/2019 07:07:40 am

It depends on the posture! Stretching postures like Hands to Feet, Standing Separate Legs Stretching and Stretching (Paschimottanasana) can use the first version, contracting the quads to release the hamstrings. Any balancing posture doesn't need a lot of attention on the knee, though it is best to avoid "resting" the femur back on the tibia as it does in hyperextension. It is best to keep the knee slightly bent in these postures, as the musculature of the leg will naturally engage effectively. The moment the leg moves into hyperextension and/or we start "engaging" muscles on purpose, the conversation gets a lot trickier. You can definitely engage all the muscles around the knee in balancing postures. It just takes a lot of effort and control to do this.

Reply

Jenna smith

3/23/2021 05:15:14 am

Which one would we be using in a pose such a standing head to knee, or standing bow?

Reply

Scott (Ghosh Yoga)

3/24/2021 08:08:52 am

In both Standing Head to Knee and Standing Bow, we are standing balanced on a straight leg. The main consideration for the knee in these positions is balance, as it is the midway point between the floor (and your foot) and your upper body. There is no significant benefit to 'locking the knee' in any of these three ways when the leg is straight and stationary.

Reply

Jenna

3/24/2021 04:00:12 pm

Thank you!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

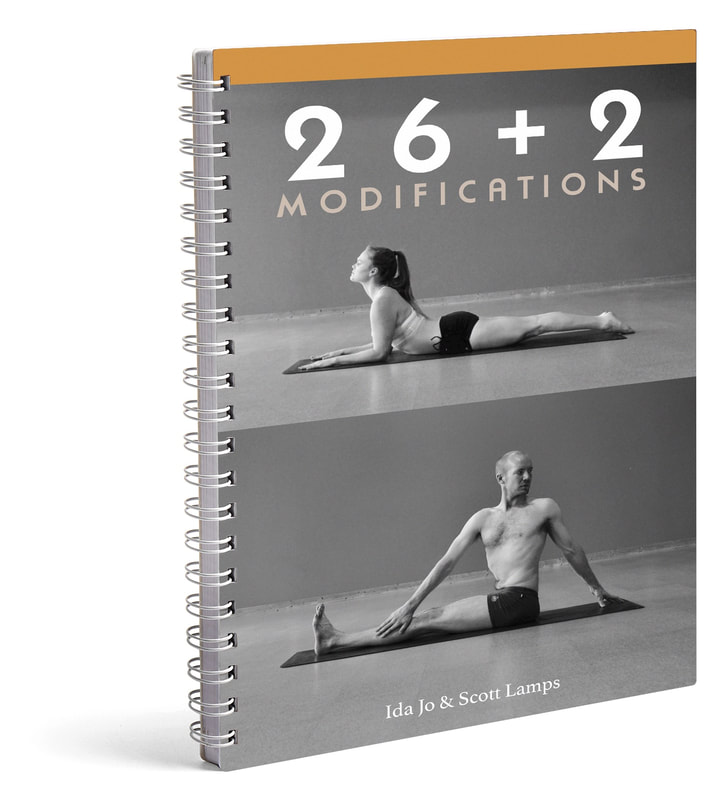

AUTHORSScott & Ida are Yoga Acharyas (Masters of Yoga). They are scholars as well as practitioners of yogic postures, breath control and meditation. They are the head teachers of Ghosh Yoga.

POPULAR- The 113 Postures of Ghosh Yoga

- Make the Hamstrings Strong, Not Long - Understanding Chair Posture - Lock the Knee History - It Doesn't Matter If Your Head Is On Your Knee - Bow Pose (Dhanurasana) - 5 Reasons To Backbend - Origins of Standing Bow - The Traditional Yoga In Bikram's Class - What About the Women?! - Through Bishnu's Eyes - Why Teaching Is Not a Personal Practice Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed